US President Donald Trump has done what was thought to be unthinkable only months ago. By slapping 50% tariffs on India, he has single-handedly pushed India into the China corner.

Indo-Sino ties were in a deep freeze post-Galwan clashes in June 2020. But ties are thawing, especially after Prime Minister Narendra Modi met Xi Jinping, China’s president, on the sidelines of the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation (SCO) summit in Tianjin recently.

“What we seek is stability and predictability in relations with China,” says Ashok Kantha, former Indian Ambassador to China. However, he says that it is difficult to speak of full normalisation, given long-standing problems, divergent strategic outlooks and China’s arming of Pakistan.

Import Inc

Trump’s tariff crusade has established one thing: in a world where protectionism is on rise, it is hard to separate geopolitics from geo-economics. Even as a cordial Indo-Sino relation is desired for strategic reasons, it is hard to ignore economic ties and tensions that these two nations share.

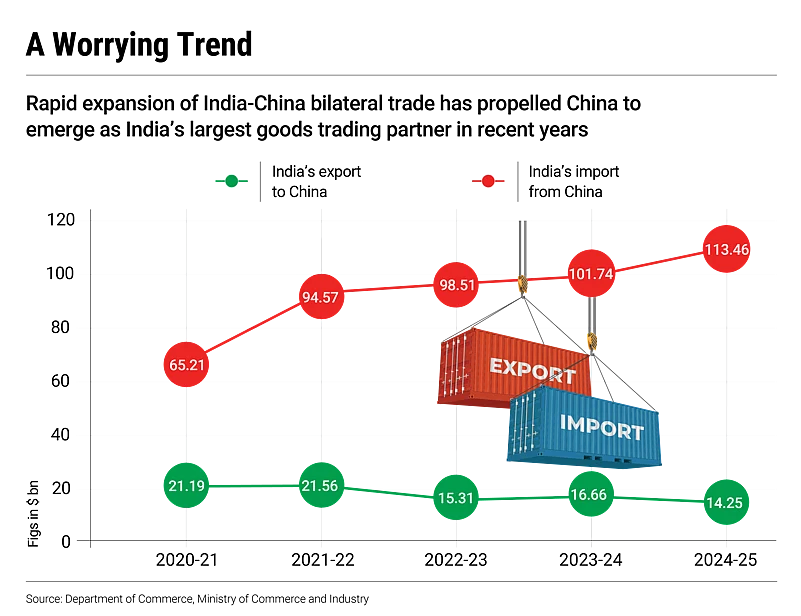

China is India’s second-largest trading partner. India’s import reliance on China is so high that even amid diplomatic tensions after Galwan, New Delhi’s trade with Beijing did not stop.

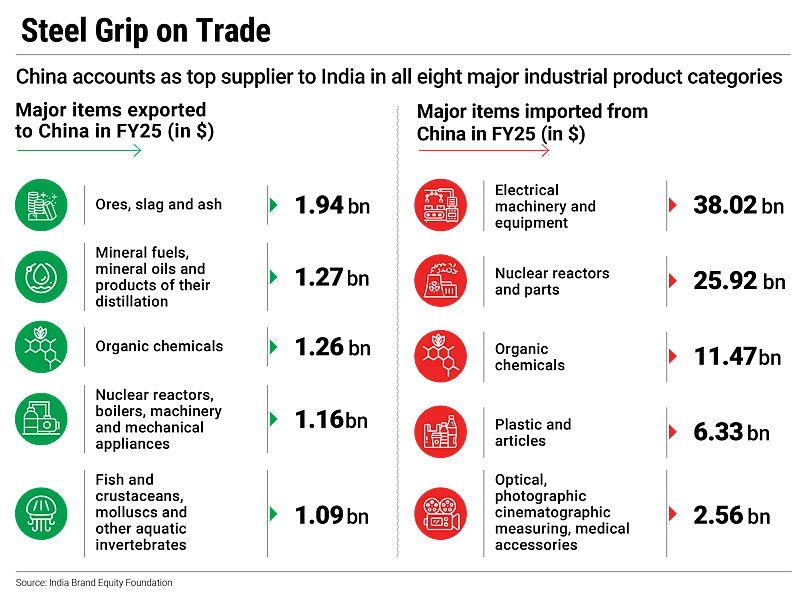

India’s trade deficit with China reached a historic high of nearly $100bn in the last fiscal. This is a result of lopsided trade relationship where China is India’s largest source of imports, accounting as top supplier in all eight major industrial product categories.

India mainly exports primary commodities like iron ore, cotton, copper, aluminium, diamonds and other natural gems.

The Indian embassy in Beijing noted that market barriers in China have stymied Indian exporters in sectors such as agriculture, pharma and IT services. In short, India is not selling what China wants to buy.

BR Deepak, professor of Chinese and China Studies at Jawaharlal Nehru University, Delhi sees very little scope for India to enter Chinese market since it’s already an export-oriented economy. “Instead, China views India as a market. We import 49% of our electronics directly from China; counting third-party imports via Vietnam, it rises to 63%. So even if ties stabilise, India cannot replace Western markets with China,” he adds.

Ballooning Deficit

In the past five years India’s trade deficit with China widened from $44bn in 2020–21 to $99.2bn in 2024–25. New Delhi’s exports to Beijing also fell sharply from $21.2bn to $14.25bn during the same period. On the other hand, India’s exports to the US, its largest market, surged from $73bn in 2021 to $87.3bn in 2024.

“[China] will not import inferior or more expensive products. China invests four to five times more than us on R&D and has done so for two decades,” says GK Pillai, former Union commerce secretary.

Under such circumstances, it is difficult for India to address its imbalances with China, which has been flagged as alarming by many analysts. Kantha says that while economic engagement with China is necessary, but it must be approached with caution.

India aspires to become a manufacturing hub. The 2014 ‘Make in India’ scheme—encouraging domestic manufacturing to create jobs and reduce import dependence—was a result of such vision. To give it push, India also adopted production-linked incentive (PLI) schemes to encourage domestic manufacturers.

India is also actively looking towards capitalising on China+1 strategy where global firms are eyeing investments beyond China.

Beijing has shown no signs of giving a leg-up to India’s manufacturing dreams. It has, in fact, imposed several informal curbs ranging from freezing fertiliser sales to asking Chinese engineers to return from India.

India Cellular and Electronics Association termed these actions as attempts “solely aimed at crippling India’s supply chains and undermining its rise as a global manufacturing hub”.

“There is a strong view in China that investing in India and building up its manufacturing could create a monster for themselves just as Western investment created a powerful China,” says JNU’s Deepak.

Not So Neighbourly

However, Yun Sun, director of the China programme at the Washington, DC-based think tank Stimson Centre, argues that China’s hesitation is not motivated by concern about India being a threat but how difficult it is to do business in India.

“That requires India to improve its investment environment, its visa and other restrictions and be genuinely receptive towards foreign investment,” she points out.

Indeed, after Galwan, India had virtually shut the door on Chinese capital mandating prior government approval for security reasons.

However, it is not like Beijing showed willingness to contribute meaningfully to India’s manufacturing capacity even when India welcomed Chinese foreign direct investment (FDI). Between April 2000 and March 2025, Chinese investment in India amounted to just $2.5bn, representing only 0.3% of total inflows, making it the 23rd largest foreign investors.

To put that in perspective, Mauritius, Singapore and the US accounted for 24.7%, 24% and 9.7% of the FDI inflows respectively during the same period.

“The inflows [from China] were small and often targeted areas where minimal investment secured large market share, sometimes even in data-sensitive sectors,” Kantha explains. Hence, he believes that it is unrealistic to expect that China will help India build its manufacturing base, especially at a time when supply chains are increasingly restricted.

On the other hand, US companies like Apple are eyeing to expand their manufacturing base in India extensively and even planning to produce entire iPhone 17s here.

Tech & Trade Off

India’s most evident dilemma lies in the realm of critical technology. India took some hard decisions on certain Chinese tech citing national security. Throughout 2020, India banned a total of 267 Chinese-linked apps. Telecom giants Huawei and ZTE were effectively shut out of India’s 5G rollout by stringent “trusted source” rules introduced in 2021.

This cautious approach extends to other high-tech areas as well. India harbours ambitions to build its own capacity in semiconductors, renewable energy hardware and defence electronics—sectors crucial for future growth and security.

India is trying to overcome China’s dominance in many of these supply chains. The efforts were speeded up after Beijing put strategic export curbs on seven critical rare earth elements and finished magnets, critical for electric vehicle (EV) motors and wind turbines, in response to tariff war unleashed by the US. The movement has slowed shipments and setting off alarm bells in India’s EV industry as 93% of India’s EV motor magnets are sourced from China.

“It’s a trade-off. If India reduces its supplies from China to mitigate risk, does it affect India’s manufacturing and export industries? India will need an alternative to Chinese supplies, a problem that many countries face,” Sun of Stimson says.

As many as 150 out of 181 countries had a merchandise trade deficit with China in 2023. With SCO members, Beijing’s trade reached to $512.4bn in 2024 from $305bn in 2018.

Certainly, the BRICS bloc (Brazil, Russia, India, China, South Africa and five other countries) alone cannot meet India’s long-term economic ambitions. With only two decades left to realise its developed-nation ambition, BRICS+—representing $32trn or 27% of global GDP—offers India limited opportunities, given that $20trn of that total already comes from China.

By contrast, the G7 (Germany, France, UK, Italy, Japan, Canada and US) with $50trn or 45% of global GDP, presents far greater potential for India’s exports and technology-driven growth.

Wary Steps

Washington, DC has long positioned India as a key partner to counter Beijing economically and strategically.

Trump’s tariff strike has somewhat risked undoing decades of diplomatic groundwork for a strategic partnership beyond Cold War legacies. But American policy wonks, for their part, have generally opposed such moves, describing them as economically damaging.

American political scientist John Mearsheimer has warned that Trump’s approach could push New Delhi closer to Beijing, just as past US policies inadvertently drove Moscow and Beijing into alignment.

In contrast the India–China mistrust, which stretches back to 1962, remained unresolved throughout. Modi and Xi’s 2019 Mamallapuram informal summit sought to ease trade frictions, but within eight months the Galwan clash took place and old hostilities resurfaced.

“Strategically our [India–US] positions have converged significantly. There are problems, no doubt, especially in recent months but the overall trajectory of ourrelations remains distinct from that with China,” says Ambassador Kantha.