Circa September 1995, Amul had just conducted its brand health survey, a ritual that the co-operative undertakes every year to understand where the brand stands in the mind of the consumer. One of the questions posed to the respondents that year was: What new products do you want from Amul? The answers varied from more varieties of butter to milk in larger packs but one particular response caught the attention of the top brass — that for Amul ice-cream.

The respondent had also put forth a strong reason: if a soap and detergent company like Hindustan Lever could sell ice-cream, what was holding back Amul, which was already in milk, butter and cheese. It was only a year earlier in 1994 that the Anglo-Dutch multinational had introduced Walls to complement its acquisition of Milkfood and Kwality ice-cream brands. Amul decided to plunge in, launching its ice-cream in March 1996, first in Gujarat and then moving on to Mumbai and Chennai the following year. It was available in most parts of the country by end-1999 and today, Amul commands a 40% share of the ₹1,800 crore organised ice-cream and desserts market. “Ice cream has been a huge success for us and continues to grow at least 19% each year.

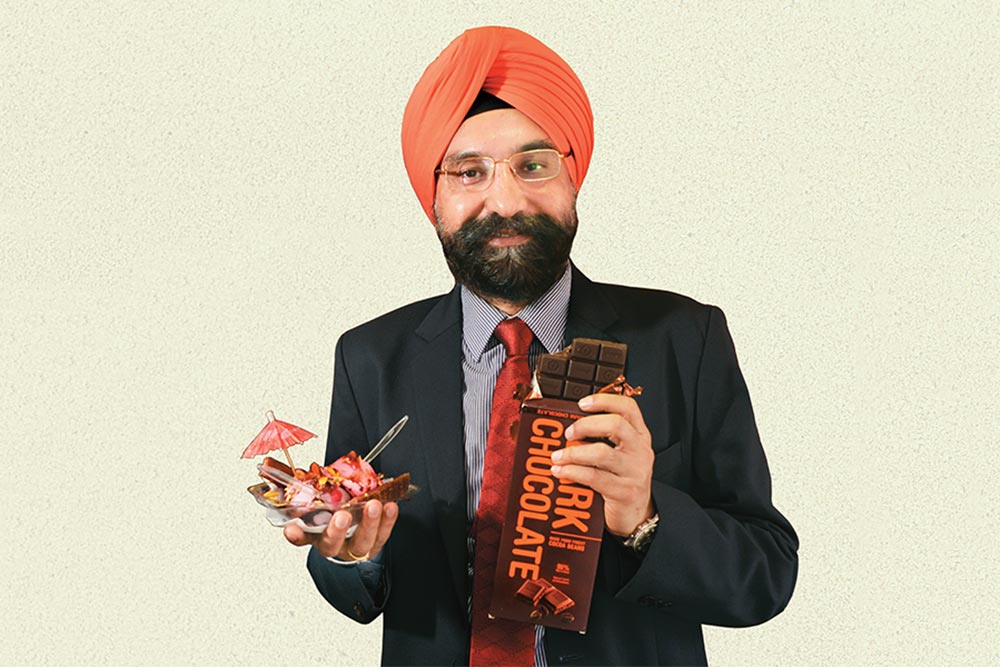

If Amul is successful today, it is because: one, we react to consumer preferences quickly and two, we have the utmost trust of our producers,” says Rupinder Singh Sodhi, managing director, Gujarat Cooperative Milk Marketing Federation (GCMMF), which owns the Amul brand. That consumer feedback wasn’t rocket science but it altered the course of the milk co-operative irreversibly feels Sodhi, an Amul sales and marketing veteran of 30 years. Incidentally, Hindustan Unilever today trails Amul with a 18% marketshare.

Having closed FY13 with a turnover of ₹13,735 crore, the management is targeting ₹17,500 crore in the current fiscal but the next big leap in Sodhi’s words, “will be to get to ₹30,000 crore by FY18.” Isn’t the language distinctly corporate for a co-operative with an objective of serving its milk supplying members? “We get the best of both worlds,” assures Sodhi with a hint of a smile. So far, that’s been true for the country’s most successful dairy player. But its nimble-footed corporate culture within a co-operative set-up is about to be tested like never before.

Sure, the dairy business is booming but competition is rising at an equally fast and furious pace. Global biggies of the dairy business have joined the fray for a piece of the milk cake in the country. If that’s not enough, domestic private players are ramping up and even some of the sleepy co-operatives are waking up to taste the cream. A crucial difference, unlike the previous years, is that the action is not in milk, butter or ice-cream where Amul has established its stronghold, but in new segments such as cheese, yogurt, flavoured milk and so on.

These new value-added segments are also the ones that will bring in maximum moolah, which means it is critical for Amul to crack these markets. The question then is can Amul maintain its lead and sustain a virtuous circle of more milk procured-more products sold?

Future proof

It’s not that the Amul management has been dozing off at a milking shed. It seems like they have been preparing for this onslaught for the better part of the last seven years. In its 2006 Hoshin Kanri — a three-day direction management meet conducted twice a year with 200 of its senior managers to chart out future strategy — some important decisions were taken.

The imminent possibility of marketing power moving into the hands of aggressive multinationals was every manager’s biggest worry. “In that scenario, it was clear we would be out of business,” recalls Sodhi. That implied a need to work harder on two ‘P’s of marketing. Amul’s positioning as a quality dairy player was already established, so it had to focus on its “product” portfolio, and the “place” or distribution machinery to ensure that it had a greater connect with consumers. Not only was a blueprint drawn out to get closer to customers, it also decided to boost Amul’s presence in value-added segments.

In the first phase, Amul opened 1,000 parlours under the franchisee route. Today, there are 7,000 outlets of which 6,200 are Amul Preferred Outlets (APO), which sell ice-creams and other Amul products. The remaining 800 are scooping parlours, where only ice-creams are served. About 125 of those scooping parlours are located in railway stations and academic institutions and there is one present in the Infosys campus in Bengaluru. Expansion plans for the next few years are more frenetic. “By 2018, we will have 12,000 outlets. The plan is to add at least 1,000 each year with most of them being preferred outlets,” says Sodhi.

Even while a retail rollout was being pursued to enhance visibility, Amul continued to work on upgrading its product portfolio. Amul had launched flavoured milk more than a decade ago under the Kool brand, and over the past six years not only has its distribution widened, it has also been positioned as a alternative to the less healthy but more popular carbonated drinks. In April this year, Amul decided to get rid of the glass bottles in which Kool was sold and moved to transparent PET bottles that looked trendier.

By doing so, Amul not only made its products appeal to a younger crowd, it also did away with the problem of high level of breakages and bottle shortage. The market response to the relaunched packaging has been encouraging and cumulatively Amul sells 15 lakh units daily of Kool, packaged lassi and buttermilk.

Then, there is cheese. Amul has been making cheese since 1962, but until 1986 it only sold standard processed cheese. Thereafter, Amul started introducing different flavours of cheese spread. Currently, it has cheese spreads — jeera, pepper, garlic, chilli flakes — that particularly appeal to Indian taste buds. This emphasis on the Indian palate is sacrosanct and something that Amul swears by. “When multinationals conduct market research, they judge the potential market. When we do it, it is only to understand the taste that the consumer is looking for,” says Sodhi.

In its search for new opportunities, Amul is continuously pushing the boundaries. The latest on the agenda: capturing the traditional Indian sweets markets. “Till now, consumers are forced to buy sweets from the neighbourhood store that rarely cares for hygiene, now they will have a better alternative,” points out Sodhi. He sees a big opportunity in creating a product line wherever dairy constitutes a substantial portion. Sounds logical but is it executable?

Method madness

The biggest hurdle for those looking to enter the Indian sweets market is shelf life. Those like burfis and pedas do not hold out for more than a week. Sodhi says every Indian sweet can be launched as long as Amul gets the technology and packaging right. Already Amul has launched basundi and gulab jamun and is working on launching kheer and gajar ka halwa over the next seven-eight months. “If technology in the West allows food to have a longer shelf life, why can’t we do it with Indian food?” queries Sodhi as he rolls up the sleeves of his Benetton shirt. Sodhi’s confidence stems from Amul’s success with paneer, a format that is uniquely Indian.

Working closely with the Anand-based, Indian Dairy Machinery Company and cottage cheese specialists from Europe, Amul built the world’s first paneer plant. “Packaged paneer is today a reality and that is no small achievement,” says the 55-year old who has not looked outside Amul since he joined them straight after passing out of the first batch of the Institute of Rural Management. It’s this bold, can-do approach that has helped Amul in growing from a small regional co-operative to a pan-India consumer behemoth. Kishore Biyani, founder, Future Group, says, “Amul does not suffer from the trappings of a multinational corporation that can limit your growth potential. You can see it in their product range.”

Currently, sweets bring in only 1% of revenue for GCMMF. However, if Amul gets it right it could take a big bite of the ₹22,500 crore Indian sweets market. Still, Sodhi is not getting carried away. He admits that while desserts will remain just desserts, its bread and butter will remain liquid milk and butter. Today, liquid milk brings in 45% of Amul’s total turnover with butter and infant food bringing in another 30%. The rest comes from other value-added products like cheese, ice-cream, buttermilk, flavoured milk, whey protein malt beverage and natural and frozen yogurt.

Clearly, if Sodhi’s ambitious ₹30,000 crore target is to be reached, value-added products will have to contribute much more. Needless to say, the ramping up of new value-added products will not be possible without Amul sourcing more milk. Three years ago, Amul started sourcing outside Gujarat from states such as Maharashtra, Rajasthan, Madhya Pradesh, Uttar Pradesh, and Haryana. Collections from these states now contribute about 15% of the total.

Interestingly, a spur in demand for value-added products was responsible for its earlier decision to procure milk from outside of Gujarat. For many years, Amul collected milk only in Gujarat and the surplus quantity was converted into value-added products such as butter and cheese, which were sold across India. In winter, when milk production typically is at least 30% more, it was converted into milk powder and white butter, which were then sold to city-based dairies.

As demand increased, it became clear that the volume of milk procured from Gujarat was not enough to meet the demand for value-added products. “We started falling short and that was not a good position to be in. Since our value-added products were available everywhere, there was no reason why we could not procure milk from other states,’ recalls Sodhi. That is exactly what Amul has done and if Sodhi has his way, at least 30% of the milk procured, by 2018, will come from outside Gujarat.

While increasing domestic demand for value-added products pushed Amul to source milk from other states, now procurement from these very states will become central to its overall strategy. It will be critical for Amul to recreate unwavering producer trust across regions and those relationships, in a way, are Amul’s real moat — an edge not easily replicable by new players and one which only a handful of cooperatives such as Karnataka Milk Federation (Nandini) and AP Diary (Vijaya) have perfected.

A visit to a village like Navali, six kilometres from Anand throws open the Amul model for public viewing. It is relatively dark at 6 AM and the farmers slowly make their way to the collection centre. About 2,000 litres are procured daily here with the average quantity being three litres. At precisely 9 AM, the Amul truck comes to pick up the milk. A 55-year old farmer, Harshal, who has been coming here for over two decades, brings in 14 litres this morning and another 11 litres later in the evening. “Everything starting from fat measurement is done in front of us and the money is given at the end of the transaction. The trust is what makes us come back here,” he reasons. What also makes the Amul model work is a promise to buy all the milk that comes its way from the farmers.

It’s part of a three-tier structure. At the first stage is the village dairy cooperative, a voluntary association of milk producers, which procures milk from farmers and hands it over to the district milk unions. This entity fixes the milk price for village cooperatives apart from processing the milk. The processed milk and milk products are then marketed by the state federation — the last link in the three-tier structure. Put together, it’s a huge community of about 32 lakh farmers and 16,914 village dairy cooperative societies. Last fiscal, these co-operatives procured 13.3 million litres of milk daily. This milk was processed in the 40 plants owned by the 17 district unions across Gujarat.

Well begun is Half done

When such stellar machinery has been created at the back-end, marketing the value added products seems like a cake walk. But even that’s easier said than done considering that no other co-operative has done it on such a large scale. Biyani says Amul’s ability to hold on to a position of dominance in a segment is praiseworthy. “Look at a category such as butter. It is hard to think of a brand beyond Amul,” he exclaims. Amul has an 80% market share in branded butter, a 60% market share in branded cheese and a 40% market share in branded curd.

Behind Amul’s marketing success is its remarkable consistency in brand communication. “That’s exactly why we have Amul as an umbrella brand and do not do things like breaking a new campaign for each season,” Sodhi explains. The Amul girl has remained unchanged since 1966 when Sylvester daCunha of daCunha Communications immortalised the icon with an utterly, butterly, delicious tagline. “From being just the flagbearer for Amul butter, the girl has effortlessly morphed into brand Amul today. The fact is Amul remains one of the few Indian brands that are left,” says Rahul daCunha, managing director and son of Sylvester, who now runs the agency that still makes ads for Amul.

Despite its long innings, there is no sense of fatigue in the Amul brand says Rahul, who created the Kool commercial targeted at the youth, “The challenge was to position it as a cool drink with health parameters. That’s why we went for the chill your dil line,” he says. However, in processed foods, be it dairy or snacks, a jazzy commercial or a brilliant tagline only plays an accessory role in its success. It is the product itself that often determines its destiny and no one knows it better than Sodhi.

It is mid-morning in Anand and Sodhi alongwith his ice-cream team is thrashing out the plan for the next season. March is a few months away, but there is buzzing activity already. The team has already come up with two new flavours — zafrani badam pista and crackling chocolate — and they are being served for tasting and feedback. Meanwhile, ways to tackle the rising cost of inputs comes up for discussion.

Someone suggests dropping the level of fat in the ice-cream. Sodhi vetoes it straight away. “Consumers identify us as a brand that delivers on quality, ingredients and weight. These are integral to the Amul story,” he says. The point is driven home quickly and swiftly. Since tweaking the ingredients is out as an option, the only other lever left to tweak is price. Given its scale advantage and not-for-profit character, Amul has always priced its products competitively and endeared itself to consumers.

Low churn here

Yet, Amul faces a considerable headwind as multinationals have upped the ante considerably. For most global players, be it Nestle, Danone, Kraft or any other, the strategy to gain market share is to flood the market with inventory and offer retailers irresistible margins. Take the instance of branded curd, where Amul falls short. A 400-gm pack that sells at ₹40 fetches ₹2-3 for the retailer. In comparison, Danone sells at a maximum retail price of ₹48 of which ₹9-10 is pocketed by the retailer.

Even an established player such as Nestle offers ₹7-8 on a selling price of ₹48. Sodhi is forthright when he says the margin Amul offers is less than exciting. “In the overall supply chain, we offer just 5% on milk, 10-12% on dairy products and no more than 20% on frozen products. We are aware that multinationals offer much more and it is in excess of 25% in frozen products,” he says.

It’s also a question of how long some of these players can sustain paying higher margins. In a category such as ice-cream, companies themselves work at barely 3-5% margin. No one could have thought back in 1996 that Amul could actually take on a consumer major like Hindustan Lever, but it did. The multinational’s former chairman, Keki Dadiseth, who was closely involved in the entry of Walls into India in the mid-1990s, recalls his company’s deliberated entry into the ice-crèam segment.

“The opportunity in India was a combination of an unorganised market, few brands and low per capita consumption. We created a premium portfolio but we did take some time to get it right,” he says. Yet, Amul raced ahead because of its sheer value proposition which meant great quality at affordable prices. It needs to be mentioned here that Hindustan Lever also had a dairy business back in the nineties — Milkana, a milk powder and Anik Ghee — which it exited in 1999.

His past success and producer linkages keeps Sodhi unperturbed about global competition and confident about future growth. “Any new player can compete with Amul only if it offers a higher price to farmers. Even if somebody manages to do that, they cannot sell at a price higher than ours. With rising overheads and higher marketing costs, they will find it hard to make money,” Sodhi rationalises. “As things stand, we handle only 4% of India’s milk production and even if that doubles, we will maintain this growth pace,” he says. That should be more than enough to keep his farmer shareholders happy.