Given the lives they live, scamsters are never short of anecdotes. Here’s one about Rajendra Sethia, a Marwari businessman who walked free last year, after a 34-year long protracted legal battle. He was accused of defrauding the government-owned Punjab National Bank of several millions of dollars in the ’80s. That the bank continues to be defrauded even today is a different story.

Though he was to be released much earlier, Sethia was rearrested in 1986 for allegedly helping the notorious Charles Sobhraj escape from Tihar jail. Now 72, Sethia has lost nearly everything over four decades — a property in London, three Rolls-Royce, two Mercedes and even a Boeing 707. But his notoriety only earned him respect!

At Tihar, Sethia was the only one among the 8,000-odd inmates to have earned the sobriquet of Saheb, and he got to know why pretty soon. One day, during a break, a fellow convict walked up to him saying: “Sethia saheb, Madan bhaiya [a notorious convicted politician from the heartland of UP] ne bulaya hain.” A nervous Sethia followed, not knowing what was in store. He had heard about an unwritten code followed at jails, wherein rapists are subjected to abuse by other convicts as rape is viewed as a serious violation of the ‘principles of crime.’ Though financial embezzlement is not considered as serious, Sethia feared the worst. But he was surprised when he came across Madan, a stout man smoking a hookah as he lay on a charpai, with a telephone close to his cot, and a frail inmate doubling as a masseur. On seeing Sethia, Madan got up and welcomed him saying, “Aaiye Sethia saheb.” That first pleasantry eventually blossomed into bonhomie between the two. Once, Sethia asked Madan, whose writ ran large behind the prison walls, why he was called Saheb. With a mischievous grin, Madan replied: “We are all here as we got screwed by the government, but you are the only one here who screwed the government. Hence, the respect!”

Recounting the episode for Outlook Business was the founder of a hospitality chain, who once worked for the Taj where Sethia, during a brief stay out on bail, had narrated the episode over a glass of scotch. The anecdote cropped up when we were talking about how 72 economic offenders had managed to flee Indian shores over the past five years, whereas a vast majority of legit businessmen in the country were not only bearing the brunt of a slowdown but also grappling with overzealous tax and regulatory authorities, who are breathing down their neck.

The hotelier, too, has been at the receiving end. He had been served a service tax notice, which he has contested, but had to pay the disputed amount before he got a hearing. This well-known ruse of tax authorities to meet the collection target is only compounding the woes of businessmen, especially when liquidity is scarce. Consider this: around Rs.3.75 trillion is already blocked in service tax and excise litigation. When the hotelier questioned the tax official about the notice, he was stunned to hear his reply. “He asked ‘Why do you worry. You will get the money back, if you win the case’. I replied, ‘What about the opportunity cost?’ His answer was ‘that’s the cost of doing business in the country’,” narrated the hotelier with a wry smile.

That the sentiment in the economy has turned perverse is evident from a corruption survey by LocalCircles, a community networking platform. It has nearly 66% of small business owners and start-ups saying that their businesses have either stagnated, or deteriorated in 2019; 34% saying that they are looking to either sell their establishment or shut shop; and 31% considering shifting base overseas for a better tax regime. A majority (55%) blamed corruption and bureaucratic inefficiencies for impeding growth. This narrative runs far and wide.

Interactions with stressed NCR-based developers — one sector in the dumps — reveal a deep distrust towards the current dispensation. “Maine apne life ki sabse badi galti kari, kamal ka button dabake. Not every real estate guy is a crook, but we are all being seen with tinted glasses. Every suggestion we make is seen as a sinister one. I am 40, but I don’t have the zeal to carry on the business any longer….I just want to go sell everything and migrate…,” says the developer who is in negotiation with a foreign real estate fund to raise capital. “I was ambitious, but the environment today is stifling. Where is the growth?” he questions, running his fingers through a grey beard, a recent acquisition that reflects his current woes.

Another developer from Gurugram also points to the increasing threat of judicial intervention. “Today, just about everyone is dragging a developer to bankruptcy court. We are not siphoning off funds, we have a liquidity issue. It’s easy for buyers to sue a builder but do they have the wherewithal to complete the project on their own?” asks the developer, who is building a residential project in the city. As per reports, 150 developers across the country are either embroiled in a legal suit or behind bars.

While the role of judiciary in settling contentious issues is on the rise, what’s unnerving businessmen and company executives is the tone of the verdicts. For instance, in the case of Amrapali builders in Gurugram, the bench of justices Arun Mishra and Uday Lalit came down heavily on JP Morgan in the case and stated: “They [JP Morgan] have a lot of properties in India. We want you to attach their offices or corporate properties of a like amount. Then they will come running to us and we will see to it.” Similarly, in the adjusted gross revenue case, the SC came down heavily on the Department of Telecommunication (DoT) and telecom companies for not adhering to its order of paying up the dues. “What is happening in this country? All these companies haven’t even paid a single penny and your [DoT] officer has the audacity to stay the order? Does the Supreme Court have no value? This is the outcome of money power. The managing directors and CMD of telcos have to personally appear on the next date if the dues are not cleared before it,” commented Justice Mishra.

A fund-starved government and bureaucracy, too, are making matters worse as statutory offences are increasingly being treated as criminal offences. For example, imprisonment without FIR in the case of GST defaults. There was also a proposal to imprison company officials for up to three years for violation of corporate social responsibility rules. Though the rules weren’t notified, jittery businessmen through Confederation of Indian Industry are now pleading with the government to decriminalise 37 laws across acts, including the Partnership Act of 1932, Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code besides those governing environment, consumer protection and labour. Former finance minister INC’s P Chidambaram, who himself was imprisoned briefly in the INX Media case, was scathing in his address during the Budget session, when he said: “Everything in this country is criminal. Now you talk about a charter of rights of taxpayers... we don’t want a charter, just take away these extraordinary powers given to these guys... that is good enough.”

Though the government is claiming that it’s making India a better place to do business, citing the Ease of Business ranking, the reality on the ground is different. Mumbai-based chartered accountant, Rashmin Sanghvi, whose clients are big businessmen and entrepreneurs, explains: “Modi’s intent to clean up is good, but empowering a bureaucracy, which has its own black sheep, is a dangerous precedent. Today, there is a fear psychosis among businessmen. If you are running a factory, there are inspectors who can slap any charge on you. A businessman can fight the authorities if a penalty is imposed on him, but he cannot fight prosecution. I have frustrated clients now saying, ‘humko dhanda hi nahi karne ka hain’.”

What has come as a big letdown for industrialists is the change in the persona of Modi. Once championing the cause of businesses and investment as the chief minister of Gujarat, Modi is now relishing his role as a messiah of the downtrodden and the one who is waging a war against black money. As Shekhar Gupta, founder, The Print, writes in his column: “The big, rich guy’s biggest fear isn’t bankruptcy, but the police. Vijay Mallya and then the Nirav Modi-Mehul Choksi duo have given corporate India a foretaste of criminalisation of economic offences… Phobias rise not from reality, but illusion.” But what is real is the all-pervasive feeling of despondency. Those who can, are doing what they can best — looking out for greener pastures either by migrating or diversifying their wealth offshore.

Foreign yearning

Over the years, the lure of foreign land has resulted in 13 million Indians turning non-resident Indians (NRIs), including one in Micronesia, a tiny collection of islands spread across the western Pacific Ocean. This is in addition to 18 million persons of Indian origin (PIO), as per 2018 data by the Ministry of External Affairs. The Gulf with 5.9 million and the US with 1.3 million are home to most NRIs.

While wealth managers and immigration agents refuse to divulge names of families or individuals citing confidentiality, they say that becoming a non-resident gives individuals greater flexibility on overseas investments. An NRE (non-resident external) is a bank account where an NRI parks his foreign earnings, whereas an NRO (non-resident ordinary) account is to manage income earned by an NRI locally. While through the NRO account, a non-resident can repatriate up to $1 million in a financial year, funds under the NRE account is fully repatriable.

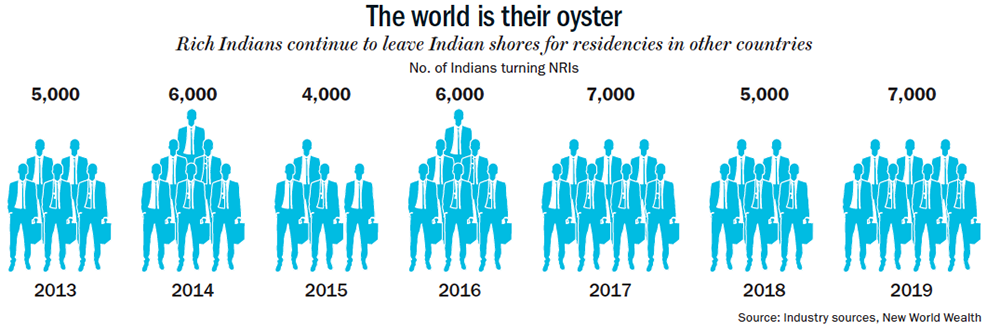

The recent Budget has made it a bit more difficult to become an NRI though — earlier, an Indian needed to stay at least 182 days abroad to attain NRI status. Now, that duration has been increased to 240 days. But the change is unlikely to dampen the enthusiasm given that already from 2013 to 2018, as per New World Report, 33,000 Indians — 5,500 a year on an average — have migrated; in other words, turned non-residents (See: The world is their oyster). According to sources in the immigration business, 2019 could have registered a peak of 7,000, last seen in 2017.

The recent Budget has made it a bit more difficult to become an NRI though — earlier, an Indian needed to stay at least 182 days abroad to attain NRI status. Now, that duration has been increased to 240 days. But the change is unlikely to dampen the enthusiasm given that already from 2013 to 2018, as per New World Report, 33,000 Indians — 5,500 a year on an average — have migrated; in other words, turned non-residents (See: The world is their oyster). According to sources in the immigration business, 2019 could have registered a peak of 7,000, last seen in 2017.

Lawyer and Congress Rajya Sabha MP, Abhishek Manu Singhvi, believes the government is missing the forest for the trees. “Highly well-off individuals would not enjoy leaving the country where they are comfortably ensconced. It is their fear of harassment, it is their fear that they are stigmatised for being successful, and is indicative of a huge trust deficit, which must engage the immediate attention of the government,” says Singhvi. Mohandas Pai, chairman, Manipal Global Education and former director, Infosys, believes besides tax terrorism, degenerating quality of life and restrictive policies and rules for overseas investments and asset creation are the other big drivers. “I have deduced this from my conversations with some of the ultra-rich who have left the country,” he wrote in a column for DNA.

Further, even as business is slowing down, the government is increasingly taxing the rich. In the FY20 Budget, the Centre had hiked the surcharge, charged on top of the applicable income tax rate, from 15% to 25% in the Rs.20 million to Rs.50 million slab, and to 37% in the Rs.50 million-plus slab. The finance minister defended the move — which was to yield additional revenue of Rs.120 billion — stating that the rich have a duty towards nation development. Further, under the Income-Tax Act, since tax liability is based on residency and not citizenship, a non-resident’s overseas income is not subjected to tax back home. Hence, it makes sense to become an NRI. Though there was a fear that the government is considering taxation based on citizenship, just like the US, when the recent Budget mooted a proposal to tax an NRI, who is not liable to tax in any other country or territory, the ministry clarified that only the domestic income of NRIs would be taxed. But what’s confounding is that since NRIs’ domestic income was always taxed, the clarification is only obfuscating the government’s real intent.

Given that convoluted interpretations are always meant to give the authorities the upper hand, many affluent Indians are seeking optimal solutions to derisk and grow their wealth. In turn, the wealth advisors are hooking up their clients with immigration agents who are making the most of the opportunity. The London-based Henley & Partners, the world’s leading citizenship planning specialist that charges $30,000-40,000 as consultancy fees, is having a field day in India.

Dominic Volek, managing partner (Singapore) & head of south-east Asia, explains: “Most of our clients don’t actually physically move. So, it’s all about sort of having a Plan B or an insurance policy. Last year, our numbers more than doubled out of India, a growth rate of 120% in terms of clients signing up for various investment immigration programmes. Further, the Budget proposal to increase the number of days to attain NRI status is making the wealthy nervous, not from a tax evasion reason but because they have a certain planning in place. They want to take a decision now rather than wait for a legislation and find it’s too late.”

New hotspots

New hotspots

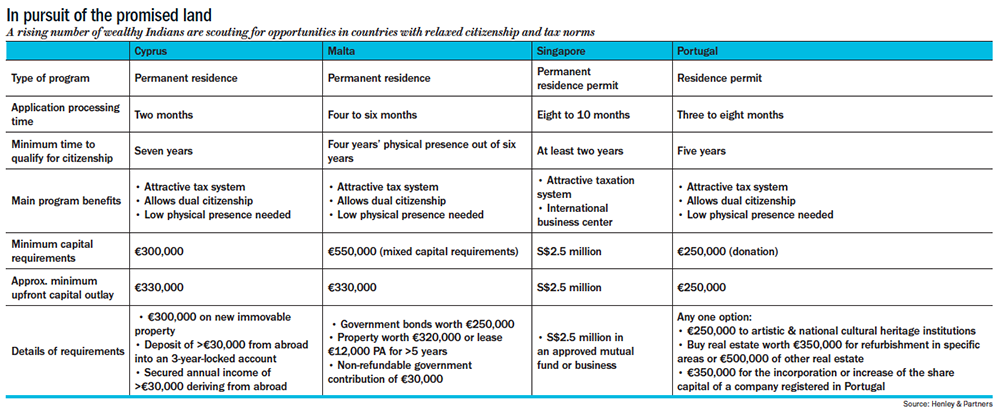

While the US, the UK and Canada have always been the preferred destination, countries such as Portugal, Cyprus, Greece, Malta, and Montenegro, are rolling out the red carpet for the wealthy by offering citizenship and residency through investment schemes (See: In pursuit of the promised land). Since India doesn’t allow dual citizenship, residency programmes are more popular with the rich as they get to retain their Indian passports.

“There’s a difference between residency and tax residency. So, all of these investment migration programmes offer you residency in terms of allowing you to learn and work, but none of them are offering tax residency which always requires some sort of additional physical presence in the country. But if you are talking about just pure residency by investment programmes that we are doing in India, Portugal is very popular because from a price level, it is about anywhere from €350,000 to €500,000, if you are going through some fund or real estate,” explains Volek. Most of the Indians signing up are in the 40-60 age bracket.

On the radar of Indians migrating are investment immigration programmes that require minimal to nil physical presence in a country. Further, given that the Indian passport ranks very low at 84th on the Henley Passport Index, an annual ranking based on freedom of travel, it makes immigration programmes all the more attractive. Portugal is popular among Indians since it requires only seven days to be spent in a year in the country and, after five years, one can apply for citizenship. However, Volek cautions that Portugal is reaching a tipping point as lot of real estate investments have been made in the market. “So, it could be a little inflated as well,” adds Volek.

Besides Portugal, an €250,000 investment in Greece can get you a Schengen visa, free access, and a resident card for five years with no minimum stay requirement. The only thing one needs to do is renew their residency permit every five years. Even in Cyprus and Malta, once a person acquires citizenship and passport, he or she does not have to spend time there. “The beauty of Cyprus and Malta is that they are members of the EU, so one has the right to stay in any of the 27 member countries without any minimum stay requirement,” says Volek. Montenegro is another destination on the radar since one can acquire its citizenship through large investments.

The UK, post-Brexit, is offering entrepreneur visa for £50,000, but if you want permanent residency, you need to spend six months a year there. While the amount has been brought down from £200,000, the new regulations are still evolving. The US EB-5 investment programme (through which people can make big, job-creating investments and acquire a green card faster) has been popular among Indians, but acquiring US citizenship is still a long drawn process. Also, it’s not appealing because of its tax proposition. “We have a lot of clients in India who studied in the US, became US citizens and moved back to India, only to realise being a US citizen is not the best idea because you are taxed no matter where you stay,” points out Volek.

Within Asia, Singapore is popular, but the investment required is high. The most popular route that costs $2.5 million is a family office with assets under management of $200 million, of which $50 million have to be in Singapore. The other avenue is the Global Investor Programme, under which one needs to invest $2.5 million in a new business start-up or expansion of an existing business operation. If it is the latter, the applicant must have at least 30% shareholding in the company if it is privately owned. One could also invest over $2.5 million in a GIP-approved fund that invests in Singapore-based companies. The UAE offers residence visa, which is valid between one and three years, but last year it announced a new long-term visa system, offering some categories five and 10-year visa, which are renewed automatically. However, the financial destination is looked at with suspicion by many governments. “Dubai is one of the few cities on the blacklists of OECD countries. In Singapore, Dubai residency is a bit of a red flag, when clients want to open accounts with a few of the private banks. So, Dubai has lost a bit of its charm,” explains Volek. While those migrating have options to invest offshore, the room for resident Indians is limited to liberalised remittance scheme (LRS) and overseas direct investment route.

Capital rush

Beginning 2004, Indian residents were allowed to remit money overseas though LRS via authorised banks without prior RBI approval, as long as it met prescribed rules under the current and capital account use. What begin with a limit of $25,000 per financial year, is today up 10-fold to $250,000. The remitted amount can be invested in shares, debt instruments and immovable property, besides expenses related to travel, medical treatment, education, gifts, donation and maintenance of relatives. Besides, individuals can hold foreign currency in accounts with banks outside India for carrying out the transactions, but they cannot trade in forex.

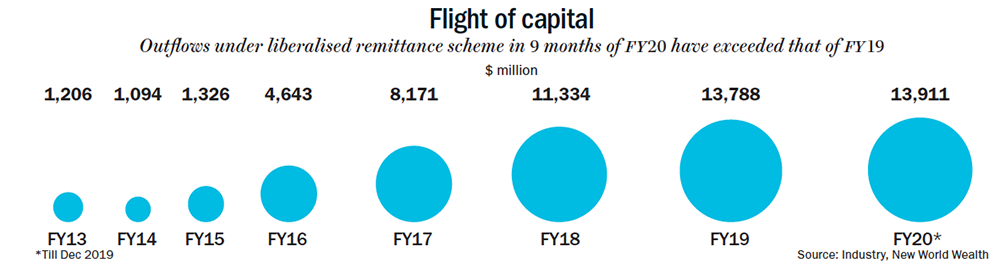

Interestingly, while cumulative outflows under these routes, from FY04 to FY14, just about hit $6.8 billion, from FY15 the outflows have been showing a dramatic increase every financial year. From $1.3 billion in FY15, outflows have surged over 10x to $13.9 billion in nine months of FY20 (See: Flight of capital). What’s revealing is that the 9-month outflow has surpassed that of FY19, which was $13.7 billion. Of the cumulative outflows seen over the past six years, $17.4 billion has been incurred as travel remittances, followed by $12 billion on studies and $11.8 billion for maintenance of close relatives. Investments in housing total to less than $500 million with investments in equity and debt touching $2.1 billion.

Interestingly, while cumulative outflows under these routes, from FY04 to FY14, just about hit $6.8 billion, from FY15 the outflows have been showing a dramatic increase every financial year. From $1.3 billion in FY15, outflows have surged over 10x to $13.9 billion in nine months of FY20 (See: Flight of capital). What’s revealing is that the 9-month outflow has surpassed that of FY19, which was $13.7 billion. Of the cumulative outflows seen over the past six years, $17.4 billion has been incurred as travel remittances, followed by $12 billion on studies and $11.8 billion for maintenance of close relatives. Investments in housing total to less than $500 million with investments in equity and debt touching $2.1 billion.

The other popular route among the affluent is overseas direct investment, wherein an individual can set up a company in India and remit 4x its networth to a subsidiary overseas. However, it cannot engage in real estate, banking transactions or raise additional money by leveraging its books. “Companies have to submit the annual performance reports of the Indian as well as the overseas subsidiary, hence, it becomes very difficult for investors to engage in any lucrative trade other than the activity for which the money is taken,” says a wealth advisor. Interestingly, a lot of individuals remit money under the head of community, social and personal services, but in most cases this is personal wealth being deployed.

It’s not surprising that Jamal Mecklai, founder of Mecklai Financial, a leading treasury and FX risk advisory company, believes it’s the dismal state of affairs back home that is accentuating the outflows at a time when private investment is falling. “We are in very difficult position right now, because to spur growth you need investment, but everyone is focused on sorting out the financial sector and getting monetary transmission going. We need people to invest in India, but today our economic financial management is virtually non-existent. There is no plan,” says Mecklai.

In 2013, when the rupee came under pressure on the back of foreign portfolio outflows, the LRS limit was lowered to $75,000 but was raised back to $125,000 back a year later. Today, given that the country’s foreign exchange reserves are at an all-time high of $476 billion, the situation seems comfortable, but a chunk of the reserves are capital flows into government debt and equities which could flow out as easy as they come. The record reserves have come also amid 60% fall in USD/INR from 45 in 2011 to 72 now. “For Indians, a weakening rupee means a significant portion of their wealth is being eroded. For the wealthy, there is no other option but to diversify overseas,” feels Singhvi.

Though the Central Board of Direct Taxes (CBDT) has stated that it hasn’t found anything alarming in rising outflows, media reports indicate that over 1,000 cases are under scrutiny. Outlook Business reached out to CBDT chairman PC Mody, but received no response. Singhvi cautions that such nitpicking is detrimental to the confidence of genuine businessmen. “The government has once again empowered ED under FEMA (Foreign Exchange Management Act). Mere suspicion can send the ED knocking at someone’s door, and that’s not a good feeling,” points out Singhvi.

Farewell, Motherland!

While the first stage of migration is becoming a non-resident by acquiring residency through investment programmes, the trend of Indians giving up their citizenship is fast gaining ground. Between 2010 and 2016, only five Indians renounced their citizenship, with nil between 2012 and 2015. But beginning 2016, 19 Indians bid adieu for good, followed by 60 in 2017 and a high of 207 in 2018, as per data, accessed by The Hindu under the Right to Information Act from the Ministry of Home Affairs.

It’s quite likely that 2019 would have seen many more Indians leaving for good, but data would be hard to come by given that, from October 2018, the Ministry of Home Affairs claims it is no longer the custodian of such information as the power to register surrender of citizenship has been delegated to Indian missions and embassies. Outlook Business tried to get comments from GK Reddy, MoS, Home Affairs, but did not get any response.

Another wealth advisor on the condition of anonymity reveals that over the past couple of years, there has been a growing unease among the minority affluent in India, with enquiries rising for the possibility of looking at citizenship via investment programmes, thanks to the narrative around the National Register of Citizens and Citizenship Amendment Act. “They don’t want to give up their Indian passports but are increasingly seeking a fallback option if things were to turn ugly,” says the Mumbai-based wealth advisor. Mecklai, too, feels that the political upheavals in the country have turned kind of vicious. “I was overseas when the news of abrogation of Article 370 came in, I immediately decided that I am going to send some money via LRS abroad. Though, I haven’t done it yet, the general state of people is one of frustration.” Volek though, believes it’s not an Indian phenomenon. “Wherever there is political tension and uncertainty of any kind, we see that happening, like in Indonesia, and Sri Lanka. So, it’s nothing more than what we have noticed anywhere else,” he says.

Even as the political narrative has got polarised of late, what’s more worrying for businessmen is that there are no signs of economic recovery and with tax collections sputtering; the harassment could just get acute. Congress leader, Veerappa Moily, who was the architect of the Direct Tax Code (DTC) and law minister during the UPA regime, believes the government can make life simple for business by implementing the code. “The DTC makes the regime simpler for businessmen so that they are not at the mercy of the tax and other authorities. More importantly, it would have curbed the creation of black money. But this government will not learn and believes using discretionary powers for political and ulterior motives,” laments Moily.

Currently, the ED is conducting investigations in 963 cases under the Prevention of Money Laundering Act, 2002, and 7,393 cases under FEMA. While the government is trying its best to assuage concerns by introducing transparency through faceless e-assessment scheme and rolling out the Sabka Vishwas Scheme to resolve all disputes relating to the erstwhile Service Tax and Central Excise Acts, businessmen are not biting the bait. “The government tried to appease the business community by offering corporate tax cut, but what did it fetch in return? Investment creation is virtually non-existent. You have to build the confidence of the business community,” says Moily.

Concurring with Moily is fellow Congressman Singhvi: “Remedial measures are many and varied, but they must be cumulative and not isolated. A quantifiable diminution in harassment by agencies, principally IT, ED and CBI; increasing the tax base as over 95% of the people are not assessed; and, last but not the least, do not treat all successful people or dissenters as necessarily crooked.”

Pai of Manipal Global also believes that migration of millionaires will continue and is unlikely to reverse, but he adds, “At best, it can be checked through policy measures for greater capital convertibility and for ease of overseas borrowings to create foreign assets.”

While India’s population is 4x that of the US, the total wealth in the country is now comparable to the total wealth of the US 90 years ago. However, the migration of the wealthy will fast outnumber the growth of new wealth creators. For now, India’s statistics look promising. The number of ultra high networth individuals in the country is 3,400, while the number of dollar millionaires stands at 343,000. Though the migration of HNIs has prompted the CBDT to set up a five-member working committee to look into the issue, there have been no suggestions or report yet.

Pai is of the view that while overseas market is good for borrowing at lower interest rates to spruce up balance sheets, “these millionaires will realise that returns are not as good as in India, which is the most lucrative market.” That may well be true, but the current mood among the wealthy is to safeguard their wealth and grow it offshore. Given that the law of the land states that till one doesn’t acquire overseas citizenship, Indians can live the good life abroad, none of the NRIs will miss home and tear up, as shown in the famous song Chitti aayi hai, watan se chitti aayi hai . Unless of course, the letter is from the taxman!