Finance Minister Nirmala Sitharaman’s investment-spending-led growth-plan seems to have impressed India Inc. It sent the fickle stock market skyrocketing and inspired corporate chieftains to heap generous praise for the minister’s bold move, without being constrained by fiscal discipline.

Does all this applause mean anything? Can the growth plan truly re-ignite the animal spirits in the economy?

Or is it like an indulgent crowd of parents at a school play?

The government is making an effort for sure. The Union Budget has allocated a capital spend of Rs.5.54 trillion for FY22, up 26% from Rs.4.39 (FY21 Revised Estimates). This, along with the spends of the public sector enterprises, brings the total capital spend for the year to Rs.11.37 trillion, from Rs.10.84 trillion in FY21.

The government is making an effort for sure. The Union Budget has allocated a capital spend of Rs.5.54 trillion for FY22, up 26% from Rs.4.39 (FY21 Revised Estimates). This, along with the spends of the public sector enterprises, brings the total capital spend for the year to Rs.11.37 trillion, from Rs.10.84 trillion in FY21.

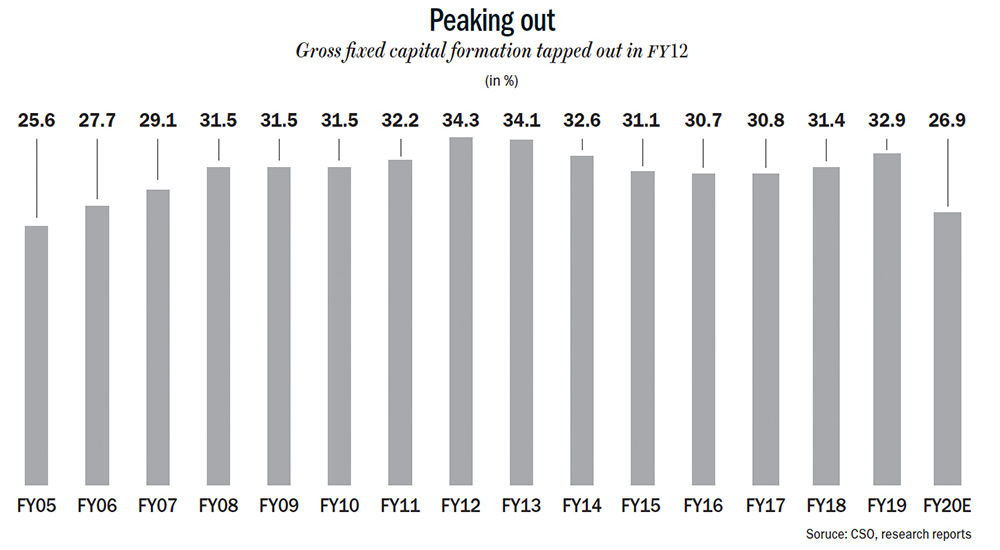

The government has to. We are at a 16-year low in the fresh investment cycle. The loss of momentum is reflected in the gross fixed capital formation (GFCF), a proxy for investment activity in an economy, which after peaking at 34.3% of GDP in FY12, has been declining. In FY20, GFCF slowed down to 26.9% (See: Peaking out). And new projects plummeted 89% year-on-year to Rs.801 billion in Q3FY21.

To move things forward, the government has been increasing its capex and the Budget is in line with that. But, whether the private sector will compliment this increased investment is quite another story.

Slowing down

The private sector is just about emerging out of a painful period of financial consolidation. The excesses from the investment boom between 2003 and 2008 and the easy credit post the global financial crisis compounded the bad loans in the banking system. After 2013, the NPA numbers became worrisome and, two years later, banks were asked to provision much more and they started becoming risk averse. Private capex began to fall after FY16.

Rajnish Kumar, advisor to Baring Private Equity and former SBI chairman, believes the policy flip flops were a big contributor to the bad loan problem. “Based on the ministry’s assurance that natural gas is available, 22,000 MW of power projects came up in the country involving an investment of Rs.1 trillion. Now that entire investment has turned into scrap because later it turned out that gas was not available.”

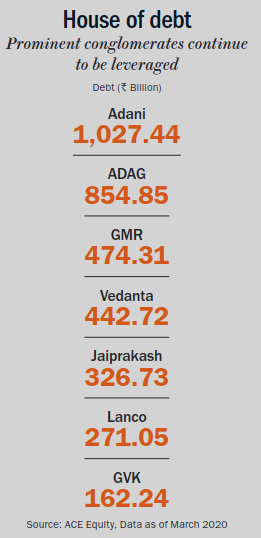

Meanwhile, the posterboys of the previous capex cycle – who accounted for up to 30% of the total investment outlay between FY07-14 – are now in bankruptcy court, according to Fitch Ratings (See: House of debt). Teresa John, economist at Nirmal Bang Securities, points out that the leveraged infra players will continue to struggle. “Though they have managed to sell off their assets, it’s clear that these players will not be out of the woods anytime soon,” she says.

The silver lining is that, barring the leveraged players, India Inc has been improving its profitability. While the cut in interest rates – 400 basis points since 2004 from 8% to 4% – has resulted in lower interest cost, companies have also reined in other costs. That has helped increase profit even where turnover declined in most sectors.

Dhananjay Sinha, director and head – institutional research at Systematix Group, believes operating efficiency, lower interest rates and lower raw material cost to sales aided in rise of India Inc’s profitability. “FY22 will see 30% growth in profitability for BSE-100 companies and 15% over FY23,” believes Sinha. As per Care Ratings, interest-coverage ratio for 3,452 companies stands at 5.3x (September 20) against 2.6x as of March 2020 (See: On a recovery path).

However, the good news stops here – India Inc is not rushing to invest.According to Fitch Ratings, a meaningful recovery in private sector investments is still at least half a decade away since capex decisions are driven by the level of capacity utilisation. And, capacity utilisation levels have been poor. “Capacity utilisation has fallen below 70%, and that has pushed back capex recovery,” says Nirmal Bang’s John, and “till it does not cross 80% on a sustained basis, capex recovery will be deferred to FY23.” Ajay Chhibber, former economist with the World Bank and currently a visiting scholar at the Institute of International Economic Policy, George Washington University, estimates current utilisation levels to be at 50%-60%, on average. He says, “We need to nurture the recovery in FY21-22 to set the stage for revival of private investment in FY22-23. Many sectors such as tourism, hospitality and mobility remain impaired. So, despite lower corporate tax rates and rising profit, investment will remain low this year.”

According to Fitch, utilisation levels of even entities with relatively strong balance sheets have persistently remained below 80% since FY14. “However, as these corporates have continued to spend on upgrading existing facilities in a bid to enhance their profitability, their capex outlay has increased, albeit at a slower pace than the previous decade.”

For instance, barring the Aditya Birla Group, which has stated that it will be ramping up capacity in Ultratech Cement, most other corporates are in consolidation mode. While Adani has been aggressive in renewable energy and airport projects, viability is still in question post the pandemic. Even as the group has bought out GVK’s holding from the Mumbai airport project, it has reportedly sought more time to take over the airports of Lucknow, Mangaluru and Ahmedabad, citing business uncertainty following the pandemic.

Nikhil Gupta, chief economist at Motilal Oswal Financial Services, says oil and gas, steel, telecom, auto and power, which constitute two-third of all private investments in the country, are unlikely to see a big pick up soon. “Except for recurring investment that is done regularly, there is no major investment or capex lined up in the oil and gas sector. In telecom, we all know how bad the situation has been over the past 10 years. I don’t think they have the capacity to invest the way they did, a decade ago. In power we have a surplus, metal is a global story, though there is some scope for pickup in business because metal prices have gone up. As far as auto is concerned, post BS-VI and given the slowdown, the tide is unlikely to change,” feels Gupta.

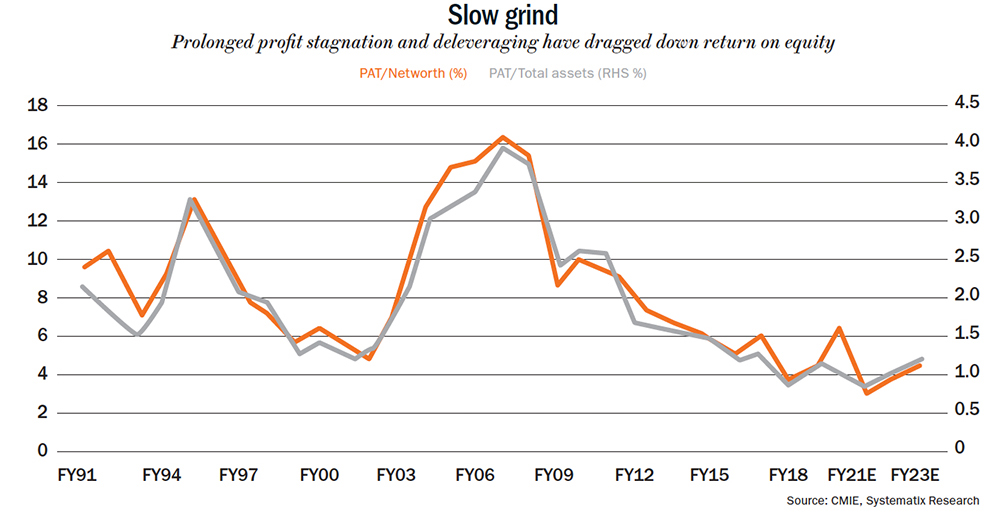

Besides, lower capacity utilisation, return ratios too are in the low single digits. “The current return ratios are in 6-7% range, while the risk-free rate is 6%. The spread between the two is too narrow for corporates to be incentivised to invest. You need an elongated and sustained period of profit growth,” says Sinha. For instance, when the 2003 investment cycle began, return ratios were around 16-17%, while the 10-year yield was 5%. According to Sinha, the return on equity of companies has come down from 16% in 2007-2008 to 3% in FY20 and is projected to rise to 5% by 2023 (See: Slow grind). “In fact, even in the previous capex cycle (1993 to 1996), the ratio moved from 5% to 14%, while profit growth for all listed companies was then 40%,” adds Sinha.

However, Gupta believes within private capex, while corporate spending will take some time to recover, revival in household investment could hold the key to recovery.

Over the past five to six years, household investment has been falling too.

Household blues

Between FY12 and FY20, share of household investments (HI) as a proportion of gross fixed capital formation declined from 43% to 39%, while corporate investments have been flat at 36%. “A large part of slowdown thus was because of a slowdown in household investment,” says Gupta. Household investments, which include investment by individuals as well as micro-enterprises, suffered because of deterioration in their balance sheets too.

According to a report by UBS, the household balance sheet deteriorated since it was funding consumption by taking higher leverage that went up to 23% of personal disposable income in FY20 from only 16% in FY12 and dipping into their savings.

Since 75% of the total investment by the households is limited to real-estate assets, the decline in income and unaffordable prices of real estate compounded the slowdown in household investments.

Surreal recovery?

The real estate sector contributes 6-7% to GDP, besides being a large employment generator. “Between FY07-13, GFCF growth was supported by a robust growth in both manufacturing and the real estate sector, driven by a rise in employment and wage growth in the services sector. The rising income levels provided a fillip to capacity utilisation of various industrial units as demand remained strong. This provided the much-needed confidence to Indian corporates for massive capex between FY13-15, increasing financial leverage to nearly an all-time high,” mentions Fitch.

Residential real estate drives a very large part of India’s investment, much larger than most other countries, be it developing or developed. Ficci stated in its report that real estate stimulates demand in over 250 ancillary industries such as cement, steel, paint, brick, building materials, consumer durables and so forth. “That is why the weakness in residential real estate is one of the key reasons why our total investments are doing as badly, except for FY18-19, when there was a small uptick before Covid struck,” says Gupta. But given that inventory levels continue to be high and the fact most real estate players are highly levered, a quick resolution will not be an easy one. “Real estate slowdown has been tackled by most of the countries by reduction in house prices. But it’s a double-edged sword because whenever that happens there will be a problem in the lenders book and so that is why this adjustment is so painful,” believes Gupta.

Though property registrations picked up to a 10-year high in Mumbai in December, the country’s costliest real estate market and also where unsold inventory levels are high, the sustainability of that is in question since the trigger was largely the temporary cut in stamp duty registration fee by the state government. But given the recent revenue loss, the state is unlikely to extend the cut beyond March 2021. While the government has been nudging realtors to cut prices, the builder lobby has refrained from initiating a steep correction. “It’s too early to stick your neck out and say real estate is a recovery phase,” cautions Gupta.

For now, the government has managed to ensure a low interest rate environment but that by itself won’t be enough to trigger a revival. “Interest rate will not be effective as far as economic revival is concerned. For economic recovery, you need both investment and saving. You can’t lower it to an extent where you incentivise one side of the equation too much. Eventually, it has to balance out,” feels Gupta.

Anyway, Kumar believes that rates have bottomed out and cannot go any lower. “I don’t think there is room for a further cut. For a capex recovery, corporates have to feel confident, only then will bank credit follow.”

At this point, a revival in capex is more of a conjecture.

Ray of hope

The only positive between the 2008 crisis and now is that demand destruction hasn’t played out as feared. “Even during the peak pandemic quarter of June, orders started coming. Unlike the 2008 crisis when orders got cancelled, cancellation of contracts was minimal, this time around,” points out MS Unnikrishnan, former managing director of Thermax and now, CEO of IIT-B Monash University.

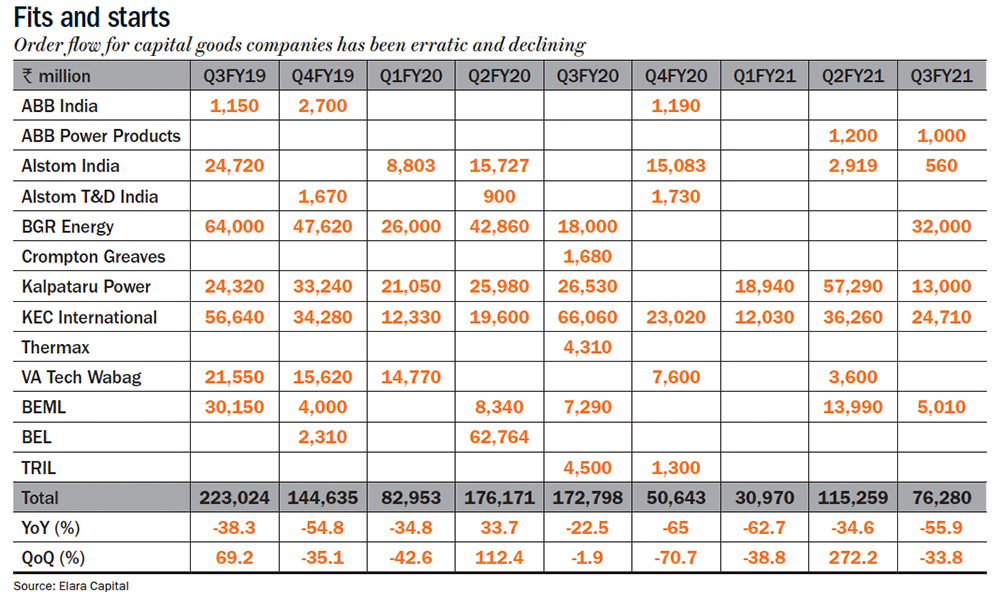

In Q3FY21, major capital goods companies (excluding Larsen & Toubro) have announced orders worth Rs.76 billion, which was down 56% year-on-year (See: Fits and starts). But if one were to include the numbers of L&T, the number looks rather impressive –- the engineering major saw fresh order inflows rising 76% year-on-year in Q3FY21 to Rs.732 billion, taking its orderbook to a record high of Rs.3.3 trillion. But, a majority of the orderbook comprises the public sector, which only shows that the onus of capex still remains on the government. While the Centre accounts for 12% of the total capex, states account for 34%, PSUs 41% and private sector 15%.

While the Production-linked Incentive Scheme (PLIS) is being seen as a harbinger of fresh investment in manufacturing, it will be a long-drawn affair. “Corporates will not invest because there is incentive to invest, instead the gains of investing have to outweigh the gains in existing business for them to leverage their balance sheets,” opines Sinha. The PLI scheme has an outlay of Rs.2.03 trillion over five years for 13 sectors of which a chunk has been reserved for mobile phones, and auto and ancillary sector. Among mobile phone makers, only Apple assemblers have applied for the PLI while Chinese handset makers are conspicuous by their absence, even though they control substantial market share. Among the major players, Xiaomi, Vivo and OPPO already have assembly units in India.

While the Production-linked Incentive Scheme (PLIS) is being seen as a harbinger of fresh investment in manufacturing, it will be a long-drawn affair. “Corporates will not invest because there is incentive to invest, instead the gains of investing have to outweigh the gains in existing business for them to leverage their balance sheets,” opines Sinha. The PLI scheme has an outlay of Rs.2.03 trillion over five years for 13 sectors of which a chunk has been reserved for mobile phones, and auto and ancillary sector. Among mobile phone makers, only Apple assemblers have applied for the PLI while Chinese handset makers are conspicuous by their absence, even though they control substantial market share. Among the major players, Xiaomi, Vivo and OPPO already have assembly units in India.

Importantly, existing MNCs have reservations over the scheme. According to a report, Ericsson India has made it clear that the draft production-linked incentive (PLI) scheme for telecom gear makers, which replicates the rules for mobile devices, will not work as the scheme does not give credit to the substantial investment that the European telecom gear maker has made in India since 1994. Nitin Bansal, managing director of Ericsson India, was quoted as saying: “We already export 5G radios from India to Australia and southeast Asia even though currently they are not required here.” The company has invested in manufacturing in India since 1994, and it wants existing investments and not incremental investment made under the scheme to be considered

Also, the capex under the scheme is not as humongous. For instance, Dixon Technologies, which makes handsets for mobile phone brands, has stated that Rs.500 million would be the capex under the PLI scheme.

For now, it seems Corporate India is happy giving back to its shareholders than investing for the future. “The dividend ratio of all listed companies has increased from 20% in FY08 to a record high 89-90% in FY20. That shows corporates are still not confident about the demand environment,” sums up Sinha.

That puts the onus on the government to keep the wheels of growth inching ahead. Much of this year’s growth will thus depend on the government’s ability to spend the budgeted sum.