We were first in the firing line,” says Ajay Bijli, chairman and MD of PVR, on being among the early establishments to be closed after the COVID-19 lockdown. The gloom in the multiplex business is thick. “This is not like a quarter on quarter situation where your occupancies dip by 5-10% and you start wondering what you will do. We are talking of revenue coming down to zero,” he says. The country’s largest multiplex operator had to shut down 845 screens across 22 states.

Yet Bijli feels lucky, as a father. Before the travel ban came into place, his son flew down from the US and his daughter returned from Mumbai. “I was more worried about keeping everyone safe and sound at home,” he says. Bijli is keeping a close watch over the health of his 85-year-old mother who lives in the same house.

“My mind space is not limited to what is happening in the business. That would be myopic or selfish. My first priority was the safety of my family and second, of course, my business and employees,” he says. Heads of businesses — CEOs, MDs or founders — are largely expressing the same sentiment, of keeping their family close. It is an anxious time.

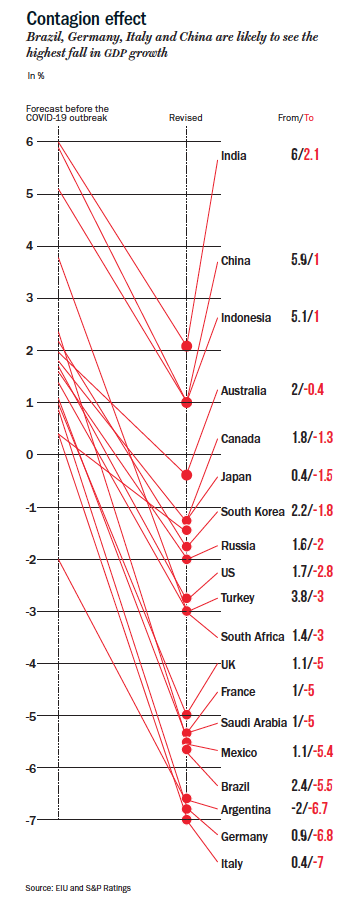

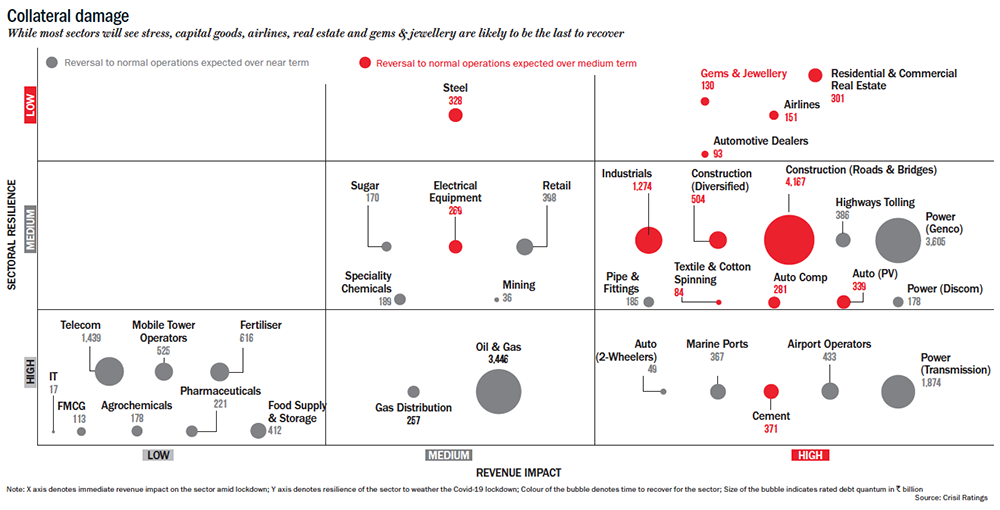

COVID-19, which has put the human race to its biggest test since WWII, is sending the global economy hurtling into recession with growth forecasts getting brutally slashed for major economies, including India (See: Contagion effect). Amid an economic slowdown that has already pushed India’s GDP growth to a 7-year low of 4.7% — despite the revised method of GDP calculation — the national lockdown could now decisively hurt growth in FY21 (See: Collateral damage).

The pandemic, according to the Asian Development Bank, could cost the global economy $4.1 trillion. Volatility has roiled just about every market with the Nifty losing 40% from its peak, rupee hitting an all-time low against the greenback, AAA yields gyrating in a wide band of 200 basis points and Brent crude diving 60%. Fear mongering though has driven gold up 12% since March.

The pandemic, according to the Asian Development Bank, could cost the global economy $4.1 trillion. Volatility has roiled just about every market with the Nifty losing 40% from its peak, rupee hitting an all-time low against the greenback, AAA yields gyrating in a wide band of 200 basis points and Brent crude diving 60%. Fear mongering though has driven gold up 12% since March.

The tsunami has hit an already fragile India Inc, in which downgrades (469) have outpaced upgrades (360) in the second half of FY20. According to rating agency Crisil, which tracks 10,000 companies, 65% credit ratings are in ‘BB’ or lower categories. Such is the enormity of the situation that the central bank at its annual meeting in March chose not to provide an outlook on GDP growth — this is just after it had estimated 6% growth in February! The extent of demand decimation won’t be quantifiable till there is clarity on when businesses can open shop.

Reality bites

The biggest challenge has been the massive migration of labour from cities to their villages. Praveen Khandelwal, secretary general of the Confederation of All India Traders (CAIT), which represents the interest of 70 million traders across the country, says that 80% of the labourers employed with traders have headed back home. According to the government, only 600,000 migrant workers have been housed across 21,000 relief camps. Some companies continue to pay for idle labour, to retain their loyalty when normalcy returns. Shrinivas Dempo, whose businesses in Goa range from shipbuilding and real estate to calcined coke, says, “In Goa, all the hard work is done by migrant labour.” The group employs over 250 labourers in its shipbuilding business, and their average labour cost is Rs.15,000-20,000. “We may have to offer them basic pay, else the labour will be gone forever,” says Dempo. To save on expenses, the group is looking at cutting down its business travel, which costs Rs.70 million-Rs.100 million a year, to a third. For the just concluded fiscal, the group is looking at a topline of Rs.15 billion.

For small traders too, it’s a bad scene. About 60,000 commercial markets all over the country have come to a halt. “Business has nosedived to just 10-15%,” says Khandelwal, adding, “The loss from the pandemic every single day is around Rs.150 billion.” Badish Jindal, who runs a steel re-rolling unit in Ludhiana and is also the president of Federation of Punjab Small Industries Association, believes the pandemic is the final nail in the coffin for small enterprises. “We don’t see business resuming for another two months, and an SME unit cannot recoup these losses for the next two years. One month’s closure wipes out a small-scale unit’s entire year’s profit of 7-8%. Given the indication of an extended lockdown, we are talking of businesses losing their capital,” says Jindal.

For small traders too, it’s a bad scene. About 60,000 commercial markets all over the country have come to a halt. “Business has nosedived to just 10-15%,” says Khandelwal, adding, “The loss from the pandemic every single day is around Rs.150 billion.” Badish Jindal, who runs a steel re-rolling unit in Ludhiana and is also the president of Federation of Punjab Small Industries Association, believes the pandemic is the final nail in the coffin for small enterprises. “We don’t see business resuming for another two months, and an SME unit cannot recoup these losses for the next two years. One month’s closure wipes out a small-scale unit’s entire year’s profit of 7-8%. Given the indication of an extended lockdown, we are talking of businesses losing their capital,” says Jindal.

Rajiv Chawla, chairman of IamSMEofIndia, which has more than 15,000 SMEs under its ambit, says the situation reminds him of the 1953 movie Do Bigha Zamin. In the depressing Bimal Roy classic, an indebted poor farmer loses his small plot of land to the local landlord, despite every effort. Chawla says, “Financially weak MSMEs and small entrepreneurs have mortgaged their homes, assets, even insurance policies for loans from banks and NBFCs. No interest waiver has been announced, only deferment of EMIs and interest, which shall be added back to the principal. Interest shall be paid on interest, having a multiplier effect! Is this relief or a debt trap for small entrepreneurs and MSMEs?”

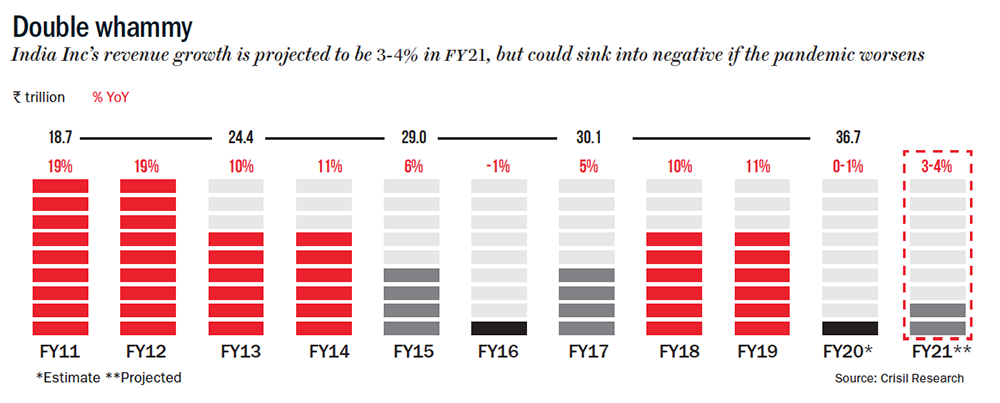

As TS Eliot had once said, April is indeed looking to be the cruelest start to a new spring (fiscal) as Corporate India is groping in the dark. According to Crisil estimates, India Inc could just about manage to grow by 3-4% in FY21, but if the pandemic spreads, there is the possibility of de-growth (See: Double whammy). There is no insurance that will come to their rescue either. Pankaj Arora, CEO, Raheja QBE General Insurance, says, “Corporates will not be able to claim business interruption damages on account of COVID-19.” Companies, usually, avail material damage policy and business interruption policy. While the former covers loss of property owing to fire, flood or breakdown in machines, the latter insures loss of profit triggered by clauses stated in a material damages policy.

Amit Burman, who heads Dabur and restaurant chain Lite Bite Foods, says that while the former is churning out essentials such as oils, honey, toothpaste and chyawanprash, the restaurant business has come to a standstill. Estimated to be making Rs.4 trillion in annual revenue, organised trade accounts for 35% of the restaurant industry. Riyaaz Amlani, CEO, Impresario Handmade Restaurants, says, “We estimate the lockdown to result in a loss of Rs.850 billion-Rs.950 billion for the organised segment. Anything beyond the original lockdown period would mean complete decimation.” The F&B major, which operates prominent chains such as Social, Smoke House Deli, and Mocha, has estimated losses for the period at Rs.200 million-Rs.220 million.

Along with restaurants, hotels are the worst hit. Patu Keswani’s hotel chain, Lemon Tree Hotels, which was on an expansion spree, has had to bear the brunt. “I have shut down about 1,400 rooms and have kept just four big hotels open,” reveals Keswani. The mid-segment player had borrowings of Rs.13 billion, as of September 2019. With investor sentim ent down, the stock hit an all-time low of Rs.17.5, compared with its all-time high of Rs.91, post its listing.

What has come as a godsend for hotel chains such as Lemon Tree, Oyo and Ginger Hotels is a tie-up with healthcare major Apollo Hospitals. The stock of the hospital chain, in a sector making the most of this situation, has gained 18% in the first week of April. Arora of Raheja QBE General Insurance says, “Average ticket price of COVID-19 treatment is rising with the entry of private players. Now it ranges anywhere between Rs.50,000 and Rs.600,000.” The partnership for Apollo’s ‘Project Stay I’ (Stay Isolated) utilises the hotels’ unsold inventory. While Oyo will be charging Rs.1,200 per room, Ginger Hotels and Lemon Tree will offer rooms at Rs.2,000 and Rs.3,000, respectively. Even IT companies such as Accenture, as part of their business continuity plan, have housed a majority of their staff across hotels in the country. “Three hotels of mine are sold out and actually my expenses are equal to my revenue,” mentions Keswani, without revealing the exact numbers.

Sundeep Chugh, CEO, Benetton India, could really do with a lifeline like Keswani got. Retail businesses, especially ones that entail discretionary spending, are in firefighting mode. March, April and May are crucial months in the fashion business. “This season is completely washed out,” says Chugh. His priorities have now changed from business growth to conserving cash by renegotiating rentals. His core team is not looking at the current impasse as a one or two-month problem, but rather one that will span a whole year. The effort, for now, is to keep one’s head above rising waters. It is not an easy task, but Chugh says spending time with his family keeps him motivated enough.

Twice bitten

Like retail, the auto industry would have given an arm to see a marginal uptick in sales. The fall in demand in the already ailing sector has intensified after the pandemic. “The industry has anyway been battling a slowdown for the past year.” explains RC Bhargava, chairman, Maruti Suzuki. The country’s largest automaker saw sales dropping 47% in March to 83,792 units, thus ending FY20 with 16% decline in car sales. “Many of our members may face dealership closures if they are saddled with unsold BS-IV stocks. We have approached the SC to allow dealers to sell BS-IV vehicles till end of May,” says Ashish Kale, president of the Federation of Automobile Dealers Association and owner of the oldest auto dealership Provincial Automobile in Nagpur. With time to kill, he has been gorging on Netflix, Amazon Prime and Hotstar. Vikram Kirloskar, who runs the show at Toyota Kirloskar, says, “The biggest issue today is will a consumer buy… the government should do whatever it takes to incentivise retail finance.” His domestic sales halved in March to 7,000 units. Following the pandemic, the company has shut its two plants with a combined capacity of 310,000 units.

While auto has been battling a slowdown, aviation, despite fairly robust passenger traffic till February, lost altitude with market leaders IndiGo and SpiceJet taking it on the chin after international and domestic flights were suspended. Though crude prices have halved, a weak rupee will increase the outgo for dollar-based costs, besides steep forex MTM (mark to market) losses on operating lease liabilities, feel analysts. Already grappling with overpricing and poor cash flows, the real estate sector is also stuck with increasing inventory. According to Anarock Property Consultants, there are close to 1.6 million units launched from 2013 till 2019 in various phases of construction in the top seven cities. With construction activity coming to a halt, it will further strain the financial health of several developers.

While auto has been battling a slowdown, aviation, despite fairly robust passenger traffic till February, lost altitude with market leaders IndiGo and SpiceJet taking it on the chin after international and domestic flights were suspended. Though crude prices have halved, a weak rupee will increase the outgo for dollar-based costs, besides steep forex MTM (mark to market) losses on operating lease liabilities, feel analysts. Already grappling with overpricing and poor cash flows, the real estate sector is also stuck with increasing inventory. According to Anarock Property Consultants, there are close to 1.6 million units launched from 2013 till 2019 in various phases of construction in the top seven cities. With construction activity coming to a halt, it will further strain the financial health of several developers.

With revenue generation down to zilch and no cash flow, corporates are doing what they know best, slashing costs. “The only facet of the business that a CEO can see today is cost. Every crisis sees a ‘react, recover and growth’ cycle. Right now, we are in the first phase,” mentions Pinakiranjan Mishra, partner and national leader, EY India.

Cutting corners

In the start-up world, alarm bells began to ring when ten global and local private equity and venture capitalist firms, including the likes of Sequoia Capital, Accel Partners, Lightspeed, Matrix Partners and Omidyar Network, in an open letter cautioned start-up founders that the macro environment could make fundraising a lot more challenging. Tracxn data reveals that Indian start-ups mopped up just $496 million through 79 deals in March, against $2.86 billion across 104 deals in February.

For Abhilash Haridas, co-founder of WeGot Technologies, an IoT-centric water utility solutions company set up in 2015, raising money was a just-in-time affair. The start-up raised $2 million in October 2019 from a clutch of investors, including Kumar Vembu’s GoFrugal, iThought’s Shyam Sekhar, and Brigade Enterprises. Haridas points out that his company is well-capitalised since sales grew 3x and profit margin grew 186% in the past year. Though raising money would be tough, WeGot is confident about closing a small round with a strategic investor in the next two to three months. “We are taking one month at a time,” says Haridas, about managing operating costs.

A whole host of start-ups have begun slashing headcount and taking pay cuts. The Softbank-funded hotels aggregator, Oyo, which is already struggling, has announced further layoffs of 5,000 people from its global workforce. It had incurred a loss of $335 million on revenue of $951 million in FY19. Other start-ups such as Bounce, Shuttl, Exotel and Acko have slashed salaries between 10-70%, besides retrenchments. The ramifications will be widespread as, according to Nasscom, Indian start-ups had generated 60,000 direct and around 180,000 indirect jobs in CY19.

But start-ups were not the first to slash salaries. Hospitality, aviation and media started it, right from IndiGo, SpiceJet and Lemon Tree to online travel aggregators such as MakeMyTrip. Bijli says that the leadership at PVR has taken a cut of 50% in their salaries. However, at the cinema operational level, PVR hasn’t resorted to any cuts. “The youngsters who are working at the unit level in any case are just above minimum wages, and so we decided we will not do much there,” he says. At Lemon Tree, with over 7,000 employees, the top 1,000 account for 70% of the company’s salary cost. “That salary [of 1,000] I will cut, but for the rest 6,000 I won’t… at least 20% of my staff won’t come back,” says Keswani.

One sector that hasn’t swung down the axe heavily is manufacturing, especially in the automobile space. Kirloskar says auto manufacturers have been improving their yields for a while now, which helps greatly in cost reduction. A yield improvement strategy is about making measurements at critical stages, such as during the casting and assembly process, besides adjusting process parameters to achieve optimal performance. With early cost-saving measures, they can afford to be generous now.

Rajiv Bajaj, managing director and CEO of Bajaj Auto, which has shut four plants, said in a TV interview that he would cut his salary to zero before sacking any employee. Even conglomerates such as the Tatas, Aditya Birla group, Vedanta group, and Essar group have reportedly promised not to cut any jobs or salaries. Tata Sons chairman N Chandrasekaran has gone one step ahead in stating that the group companies would ensure full payment to even temporary workers and daily wage earners for March and April. While retrenchment is unlikely, corporates are not going to be in any hurry to hire. The IT industry, the biggest recruiters of engineering students, and which employs four million people directly, may go slow. That puts at risk the prospects of 1.5 million engineering students who graduate every year.

Crunch hour

Cash flow is virtually drying up, and corporates and smaller companies are looking to invoke force majeure to either delay or rescind on their payment obligations. They cannot afford to not pay statutory dues even though the government has given a leeway of three months. Force majeure is an unanticipated event or catastrophe that gives the party concerned the leeway to renege on a contractual obligation.

Auto majors Eicher Motors and Hero MotoCorp have invoked the clause to suspend payments to vendors, on account of nil sales. Players in the services sector are citing the clause too, asking for a waiver on rent, which at 15-20% of sales is the biggest overhead after employee costs.

Bata India, the largest footwear retailer with 1,400 retail stores, is in fact looking to renegotiate rent. “We have urged landlords to waive the rent for the period of the shutdown. We are also looking at pegging the rentals to a store’s turnover, rather than an absolute amount,” says CEO Sandeep Kataria. Bata India has close to 200 stores in malls across the country. “This is not a partnership of a couple of months. So, we are in it together,” he adds. Similarly, Bijli is looking to sensitise the mall owners. “We are not pushing too much just now as confrontation is not the right way to go about this,” feels Bijli.

Mall and commercial property developers are playing it by the ear. According to reports, the Indian franchise of WeWork run by billionaire Jitu Virwani’s Embassy Group is not open to a complete waiver. It is asking clients to pay 30% of the rent for the period of lockdown. The RMZ Corp-owned CoWrks is not yielding at all, yet. “If the lockdown extends, we may change our position,” Siddharth Menda, founder and vice-chairman, was quoted as saying.

In the hospitality space, delayed payments are causing severe strain. For instance, early this year, the Hyderabad-based Conclave Infratech filed an insolvency application against Oyo Rooms for breaching its contract of paying the hotel Rs.130,000 every month, since May 2018. Post COVID-19, Oyo’s partner hotels are getting uneasy. Gurbaxish Singh Kohli, vice president of the Federation of Hotel and Restaurant Associations of India, was quoted as saying that “we have reports that Oyo is now coercing hotels to agree and renegotiate to arbitrary and unreasonable terms by citing the pandemic.” Amlani fears that the cash crunch will force restaurants to delay payments to vendors. “Right now, restaurants only have enough capital to pay salaries for March. We normally hold inventory worth 15-20 days, but with a hit to our cash flow, we don’t know how we will pay these vendors. Our biggest concern is that small vendors of fruit and vegetable, and meat and fish suppliers who depend on us will also see a big impact,” he says.

Baying for stimulus

Though the government has announced a Rs.1.7 trillion (0.8% of GDP) fiscal stimulus, it’s unlikely that it would be enough to get businesses up and running. Rating agency Fitch believes the package is inadequate to support an economy of India’s size amid a likely global recession. “In contrast, countries such as Singapore and the US have already announced stimulus packages worth 11% and 10% of GDP, respectively, and still are prepared to do more if necessary,” it mentioned in a report. The agency expects the government to do more and estimates India’s fiscal deficit in FY21 to shoot up to 6.2% of GDP against the 3.5% projected by the government. That could mean more pressure on the rupee, which hit a record low of about Rs.76.55 against the dollar.

There aren’t going to be easy answers yet. Meanwhile, like Bijli does, corporate heads could catch up on fun, breezy movies like Jojo Rabbit. “I don’t want to see sombre movies, because the environment is so bleak,” he says. Bijli also uses his extra hours for his riyaz (he was the lead singer of a college band, named Modus Operandi) and take lessons over Skype. In the evenings, he sings bhajans for his mother. About what lies ahead for India Inc, he says, “I am brushing up on Candle in the Wind.” That’s a song about losing a star when she was shining bright, and had so much yet to give.