In Confessions of a Shopaholic, the lead character Rebecca Bloomwood is addicted to shopping. She cannot resist a good sale and spends much more than she can afford to and ends up heavily in debt. Becky (as she is called) is chased around New York City by a collector, assigned by her credit card company, but she still cannot stop her splurging. Of course, later into the movie, she runs into a crisis and, to get out of it, goes into rehab at Shopaholics Anonymous, changes her ways and pay off her debt. Everyone is happy.

What if, the story had taken another direction? What if, when the crisis hit, Becky had access to loads of rich acquaintances who were just flinging money around? Then, the story may have ended darkly. It could have ended with Becky continuing to spend, increasingly indebted to strangers, and ultimately having a breakdown. Perhaps, she would have had to be institutionalised.

India is not exactly Becky, spending extravagantly on cashmere coats and suede boots, but it is living way beyond its means. In fact, the country is one of the most indebted among emerging markets. And today, it is faced with a fiscal crisis, and has run into a world where plenty of liquidity is just sloshing about, thanks to the 2008 global financial crisis and now the pandemic. The world’s central banks have pumped in a whopping $21 trillion — equal to a quarter of global GDP — since the onset of the pandemic.

No one can blame India for wanting to dip into that pool, and it is an ever-widening pool. But would it be wise? Let’s investigate, but with less frivolous references.

Bailout season

With so much stimulus floating around, borrowing has touched new peaks across the world. The Institute of International Finance (IIF), a global association of the financial industry, has stated in its January 2021 report that global debt has reached unprecedented levels — surging by over $17 trillion to $275 trillion in CY20. The cumulative balance sheets of G3 (the US, the EU and Japan) have expanded more than 50% of GDP last year, even as rates converged to zero-bound. And there is more money on the way.

Michael Howell, founder of CrossBorder Capital, the London-based advisory and investment management company predicts global liquidity to swell by a further $15 trillion in the current year on the back of $3 trillion-4 trillion of quantitative easing.

It is unlikely that the tap is going to be turned off anytime soon. “Paring of this liquidity infusion depends on the recovery but given the resurgence in virus cases among these countries, the reticence to normalise policy this year is high,” says Radhika Rao, economist at the Singapore-based DBS Bank. Simply put, with the virus making a comeback in some countries, their central banks aren’t too keen to pull out money. Concurring with this view, Paolo Pasquariello, professor of finance, Stephen M. Ross School of Business, points out that liquidity will depend on the evolution of the coronavirus pandemic and the widespread adoption of coronavirus vaccines across the globe, that is, on public health rather than macroeconomic or financial aggregates. “For now, the willingness of western governments, central banks and supranational authorities (such as the EU) to support financial markets and, especially, the real economy has not been wavering, despite the occasional worry by pundits and former policymakers about future inflationary pressures,” feels Pasquariello.

While the Fed has signalled that it would like a steeper yield curve, to reflect its hopes for a growth rebound on stimulus and vaccinations in the second half of the year, that may not necessarily result in a taper. In fact, the Fed has not changed its tune, of not wanting to hike for another two years at least. “While the 10-year US rates were higher at the start of the year, we don’t expect any meaningful tapering this year,” says Pasquariello. Therefore, dollar-denominated debt will continue to be cheap.

Free money

IIF believes dollar debt is back in favour because investors expect the greenback to weaken in the coming years. At present, 10% of emerging market debt is denominated in dollars. After the 2013 taper tantrum, the markets had anticipated a possible US monetary policy normalisation and higher rates, therefore emerging market governments and corporates had kept a distance from dollar debt. But this time around, the dollar is weak and there is little chance of a rate hike in the US before 2025, so borrowers are signing up for dollar-denominated debt.

India Inc has been a clear beneficiary with external commercial borrowings (ECBs) touching $36 billion as of November 2020, the second highest inflow of offshore loans in a calendar year. Last year, corporates had raised a record $51 billion. Non-banking financial companies (NBFCs) were the biggest borrowers, raising $8.61 billion, followed by financial institutions.

The momentum has continued in the current year as well with Exim Bank, the state-owned export finance institution, raising $1 billion through a 10-year dollar-bond sale to international investors at 2.25%, setting a new low in pricing. The appetite among investors could be gauged from the oversubscription of 4x as against the $1 billion on offer. Similarly, the country’s largest lender, SBI, raised $600 million through a 5.5-year dollar bond at 1.80% — the lowest coupon by an Indian issuer for a 5.5-year bond till date. For instance, in 2014, the bank had mobilised $1.25 billion via a dual tranche sale wherein the 5-year bond was priced at 3.622% and the 10-year bond at 4.8882%.

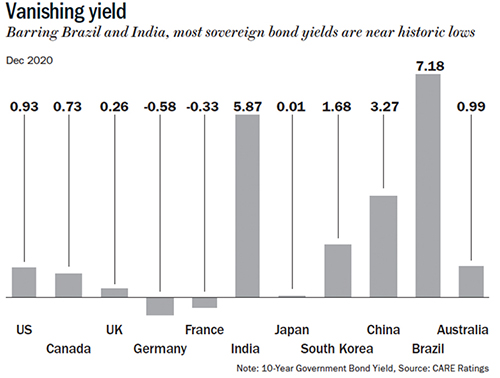

Not surprisingly, there is increasing buzz around the Indian government reviving its plan to raise dollar debt on its own books to fund its deficit. “Greater use of external financing could well appeal to many emerging market sovereigns, especially given the pandemic-related decline in government revenues,” states the IIF report. (See: Vanishing yield)

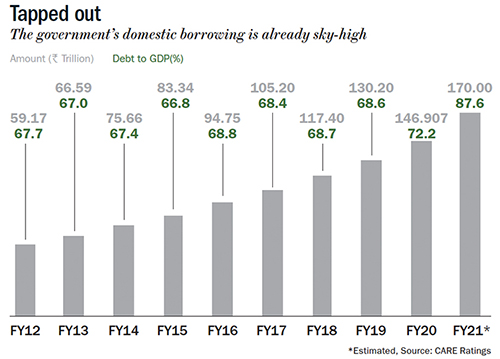

The Indian government, the biggest domestic borrower, has definitely loosened its fiscal restraint by a few notches.

Gimme more

The Indian government has targeted a borrowing plan for Rs.12 trillion ($163 billion) for the current fiscal as against the earlier Rs.7.8 trillion. It has also exceeded its fiscal deficit target by 135.1% — it was Rs.10.76 trillion in November 2020, though the FY21 budget had planned for a fiscal deficit of Rs.7.96 trillion (3.5% of GDP). The Centre has also hiked the borrowing limits of states for the current fiscal to 5% of gross state domestic product (GSDP) from 3% at present, allowing them fiscal headroom of Rs.4.28 trillion.

According to experts, the enhanced borrowing programme of the centre and states along with that of public sector enterprises is now 14% of GDP as against available resources of just 9.5% of GDP.

India is deep in debt. According to the International Monetary Fund (IMF), the country’s public debt-to-GDP ratio has jumped to 89% and would remain at similar levels till 2025. (See: Tapped Out). India has been lapping up international aid as well. In fact, despite the fractious relationship with China, India has emerged as the biggest borrower of the China-led Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB) at $4.5 billion, and also the prime beneficiary of Covid relief fund. In December, it even signed up for a $400-million loan from the World Bank (WB) to support its social assistance programmes for poor and vulnerable households impacted by the pandemic, on the back of a $750 million loan in May from the International Development Association, the bank’s concessionary lending arm.

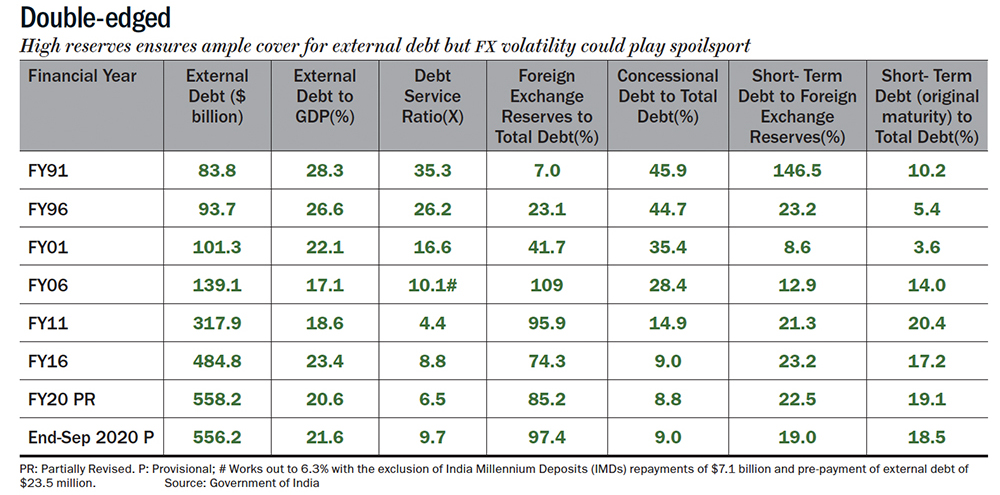

The Centre’s confidence stems from the fact that the country’s sovereign external debt to GDP is less than 5% and its foreign reserves are at a lifetime high of $555 billion. In fact, growth in India’s reserves, since the 2013 taper tantrum, is the highest amongst Asian countries. The two figures were cited by the finance ministry in a report put out last September, in which it made a case for overseas borrowing. While the finance minister broached the idea in the FY20 Budget, the buzz was that the government was looking at $10 billion in borrowing. The-then economic affairs secretary Subhash Chandra Garg said in 2019 that with rupee stable and foreign reserves going up to record levels “in terms of risk management I don’t see overseas borrowing exceeding 10-15% of the total borrowing, which makes it roughly about $10 billion.”

Rao, too, feels that, with its coverage ratios and high FX reserves, India can comfortably raise its debt level especially short-term. Besides, with dollar debt, borrowing costs are at a record low, there is a lot of liquidity among investors and there is healthy appetite for attractive yield-bearing investment avenues (See: Double-edged).

However, the overseas borrowing plan comes when there is a lot of money rippling through our banking system. Then, why do we need to raise debt externally?

Flush with funds

Since the pandemic outbreak, the central bank has lowered its repo rate (the rate at which it lends money to commercial banks in case of shortage of funds) by 115 basis points. Its repo rate is now at 4%. The RBI has also lowered its reverse repo rate (the rate at which commercial banks park their excess money with the RBI for short term) by 155 basis points. Its reverse repo rate is at 3.35%. However, even with the low rate the RBI is offering the banks, they are still parking their funds with the central bank. Bank credit has grown only at 3.2% over the nine months of FY21 — which is a near six-decade low.

Banks would be happier to lend to the government rather than corporates. Only, this could increase the cost of borrowing for domestic companies. Former RBI deputy governor, Viral Acharya who is now a professor at New York University’s Stern School of Business, had then mentioned that “an increase in government borrowing runs the risk of flooding the debt market, while making it expensive for companies to borrow”. And, the government has been borrowing enthusiastically too – India’s borrowing relative to its output has ranged from 67% to 85% since 2000, outpacing many emerging markets including China. “As more government debt floods markets, the relative safety and liquidity premium attached by investors to high-rated corporate bonds diminishes, raising the cost of borrowing especially for AAA-rated borrowers and making it relatively less sensitive to policy rate cuts,” Acharya had said.

However, Madan Sabnavis, economist at CARE Ratings, disagrees with Acharya’s crowding-out effect. “I don’t think the government’s borrowing programme is pressurising the private market in any way, nor is it pushing up interest rates. The rates are still very low for corporate borrowing. In fact, the MCLR (marginal cost of funds-based lending rate) is skewed with depositors getting a low rate but borrowers getting a very advantageous rate. Corporates are getting rates which do not reflect the true cost of capital,” argues Sabnavis.

The borrowing rates in an economy can be checked by controlling the yield curve, and Sabnavis credits the central bank for managing this well. However, analysts argue that yield is being managed not by the RBI but the government through the RBI, to protect PSU banks from volatility. PSU banks own a chunk of government securities and they faithfully hold the securities till they mature, but this means volatility can adversely impact their bond portfolios, which in turn can hurt the exchequer because the government owns these banks. “The simplest way to manage that yield is by using HTM (hold to maturity). It is a fantastic tool, it kicks the can down the road, they’ve been doing it, and they will continue to do it. On the other side, the borrowing is very significant and will continue to remain so. That is why they need to manage the yield curve,” Ajay Marwaha, a debt-market veteran and investment advisor at London-based Sun Global Investments, has said in an earlier interview.

Even the government freeing up money with the banks, to encourage them to lend to corporates, has seen only limited success. The government has over the years brought down the Statutory Liquidity Ratio (SLR) and Cash Reserve Ratio (CRR), but banks continue to park their money in government securities as SLR because they are credit averse and the government is a safer entity to lend to. The cash reserve ratio — the proportion of liabilities which a bank has to set aside as cash — has been reduced to 3% against 15% way back in 1992. Banks do not earn any interest for maintaining CRR balance. Similarly, the SLR is now 21.50% as against a high of 38.5% in 1992. Therefore, government borrowing more from the domestic banking system will further dry up finances for private companies.

The other big reason for the government to look overseas could be the potential fallout of the moratorium on the banks’ books. As of March 2020, the NPAs in the banking system stood at Rs.9.4 trillion, that is 9.4%. According to some estimates, if just 5% of loans under moratorium go bust, bad loans will bloat to Rs.12 trillion or to 12%. If the default rate is 20%, then Rs.10.2 trillion will get added to the bad loans.

Further, to pump-prime the economy, the government will have to get banks to fund private capex growth, which is already at a two-decade low. This is because the government has been a dismal allocator of capital, given that it has borrowed money to meet current expenses and the capex burden has shifted to public sector undertakings. Not surprising that rating agencies have a near-junk rating on India. Rating agency Moody’s had upgraded India’s local and foreign currency issuer ratings to Baa2 in 2017. But, in June 2020, the investor advisory downgraded the ratings to Baa3, just a notch above junk.

Against such a backdrop, can the government get better rates?

Cheap fallacy

The lowest cost of funding that India has gotten so far is for financing the Bullet Train with a Japanese loan of Rs.880 billion at 0.1% interest. But again, given that the rupee has been depreciating against the dollar and the yen by 2-3% every year, the cheap loan would not be exactly cheap. The exchequer could end up spending double the amount on the borrowing.

Further, the volatility in the benchmark rates also poses a challenge — it is hard to predict when the loan will become cheaper or more expensive, and at what rate. For instance, the 6-month Mifor (Mumbai Interbank Forward Offer Rates) swap rates, a combination of the London interbank offered rate and dollar-rupee forward premiums used by India’s borrowers to hedge exchange rate risks, hit a nine-year low at the peak of the pandemic. But the rate has since bounced back to 4.85%, a seven-month high.

History has taught us to be wary of sudden exchange rate fluctuations. For example, when the Fed made the taper announcement in 2013, the rupee fell to 68.80 against the greenback and India’s 10-year government bond yield rose to 9%. India Inc was badly hit then, since its $200 billion debt was unhedged and half of that was short term, resulting in huge mark-to-market losses. Back then the biggest setback was companies being branded as defaulters but if a sovereign defaults because of currency fluctuation, like it could now, the reputational risk is much higher. While corporates can end up as defaulters, the reputational risk for a sovereign is much higher. Though the rupee has fallen only 3% against the dollar in CY20, the fall was cushioned by the RBI as it bought $58 billion through aggressive market intervention. If not, the rupee would have been down more than 5.5%.

Besides reputational risk, a sovereign raising debt abroad also has to bear currency risk. Madhavi Arora, economist at Emkay Global, explains, “When FIIs are investing in sovereign bonds, they are coming to India and they are buying INR denominated bonds. So FIIs are taking INR risk. The moment a sovereign becomes a part of a global bond market, it starts taking currency risk.”

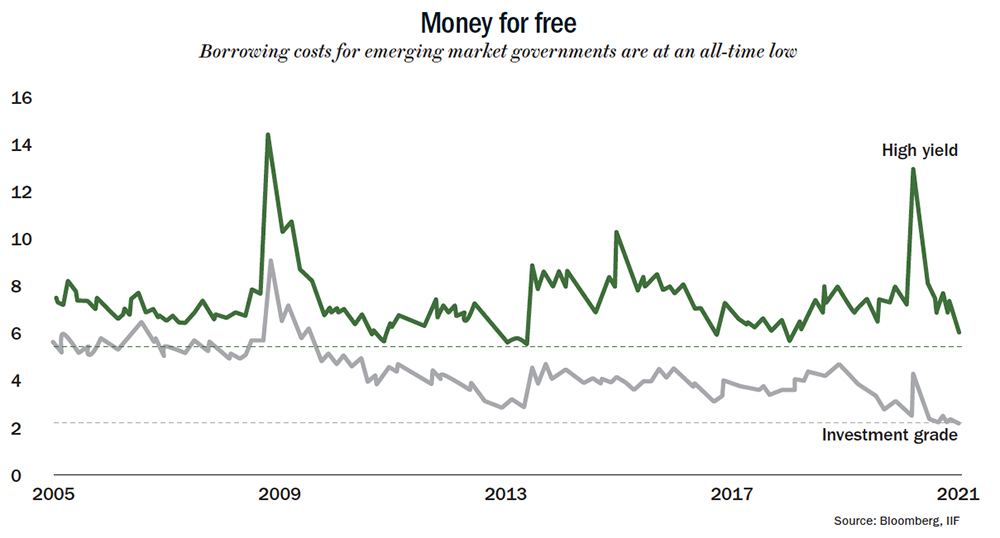

IIF feels that build-up of emerging market forex debt will only exacerbate debt-related vulnerabilities. “A number of sovereigns are planning to tap international bond markets in the coming months. Keeping debt on a sustainable trajectory may become a challenge for many in the current low-interest-rate environment,” states the IIF report (See: Money for free). That is, the governments may get money cheap and therefore tend to hoard, but when interest rate goes up, these borrowers will struggle.

Not just that, experts believe government’s overseas borrowing can also have ramification on domestic yields. “Tomorrow, the moment I start borrowing in international markets, because we are a low rated country automatically the yield goes up and that will start creating volatility in the domestic market also. Even though I maybe borrowing only 5% of my requirement I will still run this risk,” feels Sabnavis.

Despite the challenges, Rao feels that a preferable route might be to start incrementally and, over time, fix borrowings at a certain proportion of the annual issuance. But Paolo believes otherwise, “A non-trivial amount of foreign-currency denominated sovereign borrowing by the Indian government will likely have a similarly non-trivial positive effect on the opportunity for India Inc to tap into the external credit market for its growing funding needs. Any plan to tap the external sovereign debt markets right now is sound in principle but, as they say, ‘the devil is in the details’ as to whether any such plan will satisfy India’s increasing demand for external capital to grow or instead ultimately hamper that demand.”

For now, the view seems to be that the government would be better off looking inward than outwards to raise capital. Alok Sheel, RBI Chair professor, Indian Council for Research in International Economic Relations, says there is already surplus capital going out. “I find merit in Jahangir Aziz’s (chief Asia economist, JP Morgan) argument that the Indian government can expand its fiscal deficit because there is already a surplus of savings that is going out of the country and basically financing the US. The RBI investing in US treasuries is tantamount to financing the US government, and that makes no sense when there is huge fiscal requirement back home.” The RBI currently holds nearly $200 billion (over Rs.14 trillion) worth of US government securities.

Still better, Sajid Chinoy, India economist at JP Morgan and member of the Economic Advisory Council, believes it makes sense for the government to sell stakes in public sector units for budgetary resources and to drive productivity gains in such firms by bringing in private management. The economist wrote in a report that this would help limit public borrowing even while allowing the government to raise funds for public investments.

Whether that indeed is what the finance minister will do, besides what has been articulated in the FY22 Budget, will be clear in the days to come.