You must have heard about the carrot-and-stick tactic. Dangle a carrot before a donkey and use a stick to jab it from behind, thus using motivation and punishment to get it moving. The central government seems to be using this tactic with the farmers agitating against the three controversial laws that will change the face of Indian agriculture.

When the talks were ongoing, the government insisted that the laws ‘can’t and won’t’ be repealed, and its ministers suggested that protestors are misled and the NIA opened an investigation against select protestors. In this situation, the Supreme Court’s decision to stay the implementation of the three laws seemed like a timely carrot to break the logjam.

On January 5, the apex court also ordered continuation of the Minimum Support Price (MSP) until further notice and the setting up a four-member committee of experts to listen, deliberate and provide recommendations. This hasn’t convinced the farmers who worry that the committee may be partisan, and may approve whatever suits the government.

The protestors have rejected the intervention of a SC-appointed committee and continued with their demand of repealing the farm laws — Farmers Produce Trade and Commerce (Production and Facilitation) Act, 2020, Farmers (Empowerment and Protection) Agreement on Price Assurance and Farm Services Act, 2020, Essential Commodities (Amendment) Act, 2020 — passed with undue haste and voice vote in Parliament in September last year.

At first glance, the protesting farmers seem unreasonable. Why would they stand in the way of laws that are intended to better their lives and multiply their earnings? The first law relaxes restrictions governing purchase and sale of farm produce, so farmers can sell to anyone and from anywhere. The second enables contract farming, which could guarantee a sale and an income. And, the third relaxes restrictions on stocking under the Essential Commodities Act (ECA), 1955, so that one can store as much of their produce as they want, unless there are exceptional circumstances such as price hikes over 50% or 100%, or a natural calamity. Only hitch is the third benefits private parties more than individual farmers who produce to sell rather than stock and profit.

Why protest?

The puzzle mirrors the much used optical illusion of a young girl and an old crone. You either see how much the laws can help the agriculture economy or how much they can ruin it. If you are an investor or a large conglomerate, impatient to unlock the massive profit potential in this sector, you see the first. If you are a farmer, you see the demolition of a working and time-tested structure to build private monoliths, who will eventually end up dictating the price at which the farmers sell their produce.

Beyond mandis

One raw nerve the laws have touched is the mandi system. Mandis are wholesale markets maintained by the state, under the Agricultural Produce Market Committee (APMC) Act. Farmers bring their produce to the mandis to sell it to licensed traders or government agencies. This is supposed to ensure transparency in determining the price and to ensure that the farm-to-retail spread (or the difference between what the farmer is paid and what the consumer is paying) does not reach excessively high levels.

This system has its flaws, for sure. There are complaints that these mandis have become monopolistic dens, with intermediaries and large farmers calling the shots. The mandi committees do everything possible to limit competition. “Obtaining a licence for a new entrant — whether a regional trader, processor, national or multinational corporation, or farmer producer organisation — has most often proved to be a bureaucratic nightmare and a costly affair,” notes Mekhala Krishnamurthy, Senior Fellow at the Centre for Policy Research and Associate Professor of Sociology and Anthropology at Ashoka University, in a column in The Indian Express.

Additionally, there are simply not enough mandis. The Doubling Farmers’ Income Report 2017 estimates that, in some states, an APMC serves a geographical area of 496 sq.km as against the recommended one for every 80 sq.km. So, a vast majority of the small and marginal farmers sell their produce to small-scale and largely unlicensed traders and intermediaries in villages or local sites.

The FTPC Act 2020 will bypass these mandis and commission agents to create ‘One Nation,-One Market’. It will allow anyone to buy produce from anywhere, without having to procure a licence, pay any tax or even declare the inventory they are acquiring.

This law, along with the other two, could rid the sector of the licence raj, according to Mark Kahn, co-founder of agritech focused investment fund Omnivore. “This (licence raj) has in fact held back investment for many decades in the sector,” he states. For instance, the earlier version of Essential Commodities Act held back investment in modern agricultural infrastructure, including storage, logistics, export facilities, and food processing. According to him, with the new laws, the sentiment will improve with SMEs, start-ups and corporates being able to directly deal with farmers.

Though Kahn is optimistic, Bihar’s experience with deregulation does not inspire confidence. In 2006, the state repealed the APMC Act, but it did not transform the agricultural market as had been imagined. Despite restrictions being lifted, corporations did not rush in to directly procure from farmers. In fact, they just used the existing system, ridden with intermediaries, to their advantage. “They chose to buy from larger traders and aggregators and not from farmers,” writes Krishnamurthy in her column. Small and marginal farmers were still left holding the short end of the stick.

In fact, deregulation could introduce risks into the system. “Across the three new acts, the invisibilisation of trade is a real risk,” explains Krishnamurthy. “For example, stock limits have been eliminated, but there is no mechanism for declaring inventories. Unregulated trade has been legalised but there are no systems yet for recording prices and market information. These are important for competitive trade.” That is, a big corporate buyer can simply create a capacity of 100 million tonnes and procure most of the onions produced in the country. Then, he or she can decide the selling price, which could undercut a small farmer, besides affecting consumers.

Is there then a happy medium, between the poorly functioning mandi system and a deregulated platform? Karnataka tried a model in 2014, with Rashtriya eMarket Services (ReMS). Through this, the state connected about 157 of its 162 agri-markets to the United Markets Platform (UMP), a portal that facilitates online bidding for produce.

The system is simple: Farmers bring the produce to the nearest markets, where it is listed on the online platform to be auctioned to traders from other states as well as institutional buyers like Cargill, ITC, Reliance, Godrej and PepsiCo. The bidding opens at 9 a.m. and closes at 3 p.m. Farmers get price alerts through SMS and can accept or reject the offer instantaneously. Apart from providing efficiency and transparency, this system also tries to break the nexus of middlemen and enables farmers to get a fair price for their produce.

At present, the system isn’t as efficient as it should be, largely due to lack of awareness among farmers and their limited resource pool. For example, farmers often take loans from trading agents to pay for transportation or other purposes, and thus do not have the luxury to demand competitive bidding. Even if they do, the middlemen end up taking a cut. But the Karnataka model does provide a workable alternative.

At present, the system isn’t as efficient as it should be, largely due to lack of awareness among farmers and their limited resource pool. For example, farmers often take loans from trading agents to pay for transportation or other purposes, and thus do not have the luxury to demand competitive bidding. Even if they do, the middlemen end up taking a cut. But the Karnataka model does provide a workable alternative.

To MSP or not to

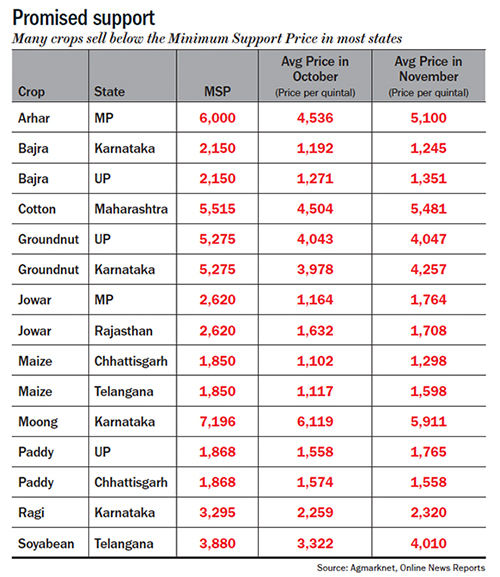

Besides the fear of collapse of the mandi system, what worries the farmers gathered at the Delhi borders is the withdrawal of the minimum support price (MSP). Simply put, MSP is the price at which the government purchases from the farmers, which ensures the farmer makes a profit (however small) every harvest. Despite the farmers not being paid full MSP, it is a crucial safety net (See: Promised support).

Here’s why

The prices of agricultural commodities have been low in the past, due to political reasons and the sector’s economics. Firstly, due to political reasons, the government does not allow food prices to go up uncontrollably, since it drives up inflation. Secondly, the agricultural products’ economics is such that demand is not elastic — as income grows, food consumption doesn’t grow in tandem. While these factors cap the upside, MSP offers a fragile protection on the downside. Taking MSP away would be disastrous for farmers.

The MSP system is faulty too, like the mandi arrangement. Farmers grow more of the crop that earns them a subsidy, which causes an imbalance in the food supply. Post-independence, the government used to announce MSP for 23 major crops including edible oils, pulses and cereals. Almost every farmer grows one of these. In the 1990s, after the economic reforms, the government changed the Public Distribution System (PDS). So now, the Food Corporation of India (FCI) actively procures only rice (paddy) and wheat under PDS, and its warehouses are overflowing with the grains. As of September 2020, the FCI had 47.83 million tonnes of wheat instead of the required buffer stock of 27.58 million tonnes. Similarly, it had 22.19 million tonnes of rice instead of the required buffer of 13.54 million tonnes.

Several economists, including former member of the Planning Commission Abhijit Sen, have alluded to the MSP being unsustainable for the economy. Kahn, too, believes that an assured MSP for FCI purposes is fine but insisting on MSP for all private procurement will be disastrous for Indian agriculture. “The system of MSP we built in India (in 1966) was to ensure farmer welfare. But the tools we have at our disposal are much more precise in 2020. Using government-set commodity prices to deliver farmer welfare is like using a sledgehammer to do surgery when we can now use scalpels and lasers!” He instead points to solutions like direct cash transfers, noting that the Kisan Samman Nidhi Yojana could be radically increased from Rs.6,000 to Rs.60,000 per year instead of continuing with older schemes and subsidies that encourage overproduction of surplus commodities.

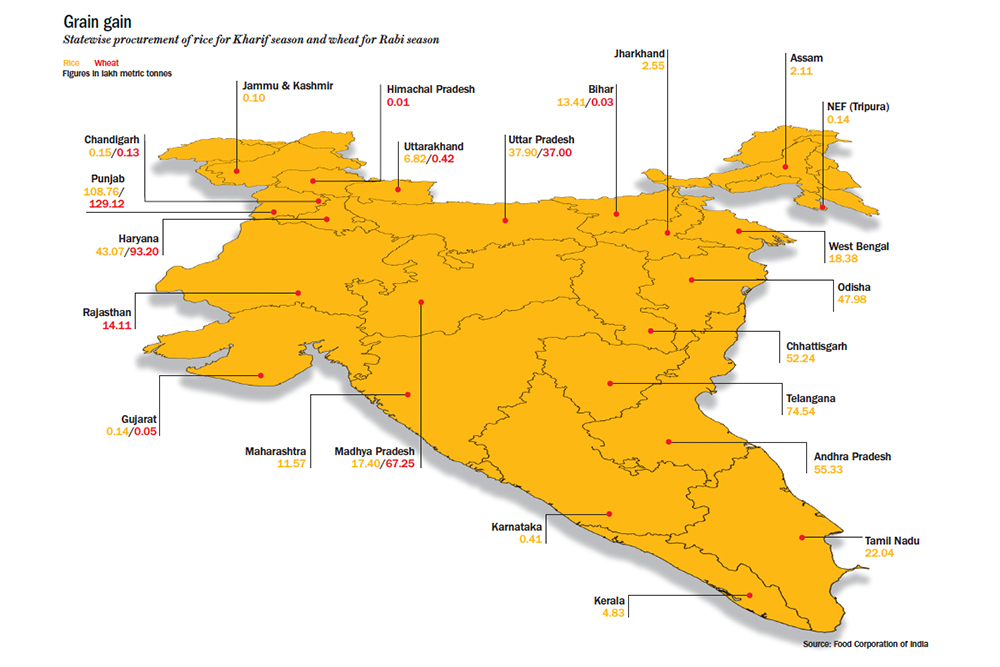

If government procurement is reduced or if MSP is discontinued, the price of rice and wheat will fall. This will result in serious loss of tax revenue for states that are heavily dependent on procurement by FCI (See: Grain gain). Among farmers, it will hurt the bigger players more. A paper published by the Commission for Agricultural Costs and Prices 2020-21 states: “As indicated by data received from some states, medium and large farmers occupy a major share in total procurement in the State and the share of small and marginal farmers, though improved during the last few years, remains low”. Under the new system, as under the old, small and marginal farmers cannot be sure of a better outcome.

If government procurement is reduced or if MSP is discontinued, the price of rice and wheat will fall. This will result in serious loss of tax revenue for states that are heavily dependent on procurement by FCI (See: Grain gain). Among farmers, it will hurt the bigger players more. A paper published by the Commission for Agricultural Costs and Prices 2020-21 states: “As indicated by data received from some states, medium and large farmers occupy a major share in total procurement in the State and the share of small and marginal farmers, though improved during the last few years, remains low”. Under the new system, as under the old, small and marginal farmers cannot be sure of a better outcome.

Connecting dots

Finally, there is the spectre of contract farming. Typically, under contract farming, a farmer grows a particular type of crop on his own land for the buyer (a private corporation). The price is usually pre-determined, which is a big advantage for farmers. The buyer usually provides a farmer with input materials like seeds and fertilisers, advanced technology and technical advice for production. All this helps in improving the yield. In case of a dispute, the local sub-divisional magistrate can intervene.

Sounds perfect, doesn’t it? The flipside is that a farmer faces the risks of both market failure and production problems. Himanshu, associate professor, Jawaharlal Nehru University cites the example of a chips company, which procures potatoes from farmers. “The machines will accept potatoes of only a particular size and shape. But nature doesn’t produce like that. So, the chips company will buy only the good ones, and reject the rest saying they aren’t of desired quality. There is little a farmer can do,” he says. Under the written contract, the farmer has to compensate the sponsor/buyer and the farmer may be forced to sell his only asset, his land, if he does not have enough capital. On the other hand, if the farmer wants to challenge the buyer, he can go to court but rarely can a farmer afford the expenses of a lawyer to take on a corporate’s battery of lawyers, or the time to fight the case.

Besides, at this point it is hard to say how corporate farming would change the landscape and affect small and big farmers. In a Newslaundry article authored by Basant Kumar, farmer Sunara Singh says that it is only the ‘big farmers’ who benefit from contract farming as they get easy access to corporates looking to buy in bulk. Singh cultivates about 15 acres in Fatehpur and has been selling potatoes to PepsiCo for many years. “Ask any farmer who wants to sell just a few kilos of produce, they are not even spoken to cordially there,” says Singh.

Not only can big farmers cut better deals with corporates, they also have facilities to stock their produce when prices are low. A big farmer can also provide consistent quality and quantity required by corporates. In contrast, a small farmer does not have the bargaining power and the storage facility, and cannot guarantee the quality of the produce. They are therefore forced to sell at whatever price.

With most farmers in India owning land of less than two acres, there is little that contract farming can do for them. Sure, corporates might be able to consolidate small and marginalised farmers in a particular region to fulfil their procurement needs. This might bring in more efficiency and bring down the cost of production. But in the process, the prices will go down further, making the farmers fearful of becoming manual labourers on their own land.

Whether it is the highly regularised old order or completely deregularised new order – both overlook the needs of 86% farmers in India — the small and marginal farmers. They lack technical knowhow required to improve quality of production, and financial muscle and bargaining power owing to small quantities of produce.

Krishnamurthy says that a change in farm laws in itself will not automatically increase the income of farmers. For real transformation, there has to be more clarity on who works with whom, how contracts are structured, how price benchmarking occurs and how procurement is monitored. There also needs to be talk between states, centre and farmer unions on how much investment needs to come in from private players, which segments of agriculture require these investments and how the entire supply chain can be made more efficient.

“I don’t think anybody would be enthusiastic if our financial markets were reformed in this manner. Nobody would have said let’s deregulate, have regulatory fragmentation and a regulatory turf war between state and centre,” says Krishnamurthy. Instead, she says, there is a need to rollback big declarations of laws being revolutionary. The solution lies in the details.