Ten years ago, Kamlesh Kumar was proud to join a Noida-based tile manufacturing company at a monthly salary of Rs 25,000. Like any first-time earner, the young commerce graduate from Patna in Bihar had dreams: buy a car and purchase a small apartment, even if it meant a stretch. Loans and a little family support would get him there, he was sure.

Those were heady times for the economy. India’s GDP had expanded a robust 8.5% in 2010 and Kumar, like most Indians, was optimistic.

Cut to 2021: it’s been a decade since his first job and 31-year-old Kumar’s wheels are a Honda Activa scooter. He lives in a 2BHK rented apartment in Noida with his wife and two children. This is despite the hikes he got from four job changes. He’s stoic but at times, gives in to lament: “I am practical now. Not everybody can own a car and a home in this city.”

Kumar’s inability to afford at least a car, even if not a home, lies at the nub of a searing question before India’s policymakers, thought leaders and civil society: has the world’s sixth-largest economy, that has been chasing the elusive double-digit growth for two decades, failed its tens of millions of citizens aspiring to lead a middle-class life?

The unmet dreams of Kumar and millions of his peers are showing up, aggregated, in the crimped demand in the economy. Earlier this month, Ford Motor Company announced its exit from India, citing losses of over $2 billion in 10 years. Earlier, Harley-Davidson and General Motors, too, had packed their bags, cutting their losses. Some of this could be traced to the inability of the US majors to dovetail their business models to the acutely price-sensitive Indian market. Still, it is telling that in the second decade of what is said to be the Asian (nee Indian) century, auto sales contracted 1.5% on a compounded basis—not in one or two years’ time frame but over a longer period (2010-11 to 2020-21)— when it should have easily included the likes of Kumar with better income growth. (See chart: Passenger Vehicle Sales In India)

Beyond anecdotes, there is a crimping of income at the national level. And for those who point to the record Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) inflow of nearly $62 billion in the last fiscal year, a gentle reminder: more than half of that amount was by way of investments by the likes of Facebook, Google parent Alphabet and others into the Reliance Jio units.

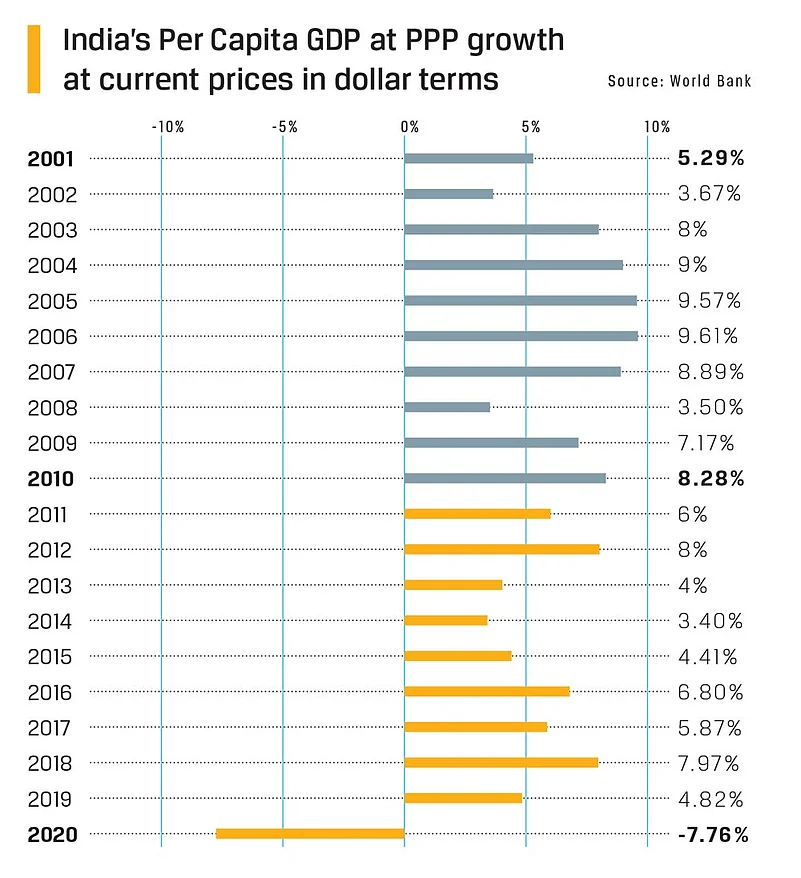

And, to be sure, the trend is not recent. The slowdown is a decade old. As per data from the World Bank, between 2011 and 2020, India’s per capita GDP calculated on purchasing power parity, at current prices in US dollar terms, compounded 4.3% annually—about half the growth of 7.2% in the preceding decade. (See chart: India’s Per Capita GDP Growth)

Covid-19 has reset gains made in the last three decades. A Pew Research Center report released in March this year showed that a third of the Indian middle class had lost incomes when the first Covid-19 wave hit India in mid-2020. “Middle class in India is estimated to have shrunk by 32 million in 2020 as a consequence of the downturn compared with the number it may have reached absent the pandemic. This accounts for 60% of the global retreat in the number of people in the middle-income tier.” India led with the most number of people (75 million) falling into poverty in the economic devastation after the first wave of Covid-19. The situation could be a lot worse after the devastating second wave hit India in the summer of 2021 but no estimate is available yet.

Prior to the pandemic, it was anticipated that 99 million people in India would belong in the global middle class in 2020, as per Pew, a US survey and research agency. According to the agency, a person with an income between $10.01 and $20 a day—roughly between Rs 22,200 and Rs 44,400 a month— belongs to the middle class.

The Pew survey needs to be seen against the 2011 projection made by New Delhi-based National Council For Applied Economic Research in which the organisation had estimated the Indian middle class to grow from 31.4 million to 267 million by 2015-16. As per the NCAER survey, a person earning Rs 340k to Rs 1.7 million per annum (in 2009-10 prices) belongs to the middle class.

The two reports, prepared 10 years apart, raise two crucial questions. First, why has India failed to create a middle class in the last 10 years? Second, with an already anaemic middle class shrunk by Covid-19, how long will it take the economy to generate the demand that will see global companies stay invested here and provide jobs?

Lame duck consumption

The second decade of the 21st century began on a positive note. India also seemed to have decoupled itself from the global financial crisis of 2008 with just one year of sub-5% GDP growth. Consumption was strong and kept the India engine humming. But there was a deadly undercurrent: household spending was fuelled by debt.

“Private or household consumption has been the bulwark of growth in the Indian economy,” says Dipti Deshpande, principal economist, CRISIL. “During the fiscal 2006-2017 period, private final consumption expenditure (PFCE) grew at a healthy pace of 7% on an average. This story somewhat changed in fiscal 2018 when consumption growth started somewhat decelerating as income growth slowed (proxied by lower GDP growth). The average Indian, however, supported some part of his consumption by dipping into savings as well as taking on somewhat higher leverage,” she says.

India’s household financial savings, which averaged 13% of the GDP up to fiscal 2015, came down to 11% by fiscal 2020. By the December quarter of 2020, household savings dropped to a low of 8.2% of the GDP. “Given that the second wave led to increased medical expenditure, both in rural and urban regions, it is likely that household savings would have shrivelled further,” adds Deshpande.

According to the All India Debt & Investment Survey conducted by the National Statistical Office, between 2012 and 2018, the average debt of the country’s rural households shot up nearly 84% to Rs 59,748 by June 2018 from Rs 32,522 in 2012. Rural incomes were clearly hit. In the case of urban households, it increased by 42% to around Rs 120k in the same period. “With weak income growth but stable consumption growth, it became clear that India’s growth was supported by savings withdrawals and the accumulation of debt by households which stretched their financial positions,” Nikhil Gupta and Yaswi Agarwal, analysts of brokerage firm Motilal Oswal Financial Services, wrote in a research note. (See chart: Share of Consumption…)

Kumar, the tile factory executive in Noida, is a case in point. By 2014, his annual increments had stopped matching steps with his dreams and his lifestyle. Credit and dipping into his savings were his two options to keep his lifestyle going. The remnants of high inflation of the UPA-2 years, which was reined in only by mid-decade, also pinched Kumar and his family. While the crude oil crash of 2014 tamed inflation, the Indian middle class was in for a ruder shock in 2016.

Demonetisation and the death of small businesses

On November 8, 2016, when Prime Minister Narendra Modi made a late-evening announcement on TV about India yanking out high value notes of Rs 500 and Rs 1,000, it was met with disbelief. Few had heard of the word ‘demonetisation’ and it took some days for the understanding to set in. Beyond the front-page images of snaking queues as people rushed to deposit cash at banks, the impact on the immediate GDP growth was not much. India did well to report a growth rate of 7.1% for fiscal 2017, reflecting how large companies had benefited from the formalisation of the economy.

But, there was a deeper casualty: small-scale businesses that operate in the country’s informal sector. As per the National Sample Survey Office, the informal sector accounts for approximately 40% of India’s GDP and employs three out of four Indian labourers. As SMEs lost business to the corporates, which haven’t created new capacities in the last decade, it harmed the long-term goal of increasing the size of the middle class that would consume products.

Pronab Sen, the former chief statistician of India, asserts that against popular belief, it is the SME sector that launches people from the low-income group to the middle-income group. “You will see profits of the Indian corporates going up post demonetisation and GST. But it was the opposite for SMEs,” he says.

Apart from anecdotal evidence and some studies by trade bodies, the real hurt demonetisation caused to India’s informal sector is yet unknown as an impact survey for MSMEs during that period is yet to be conducted.

Missing: Corporate investments, new jobs

For over two decades, the writing on the wall has been clear for India: the best way to raise incomes sustainably is to move labour by the millions from fields to factories. But, despite all efforts, apart from pockets, growth in manufacturing jobs has been a trickle. Well-paying jobs have been mostly created in the services sector, which accommodates a very small segment of the 460-million workforce. Most of the others do informal and gig economy jobs.

Mahesh Vyas, managing director of Centre for Monitoring Indian Economy, recently wrote in The Indian Express: “In a country of over a billion adults, there are less than 80 million salaried jobs. Where would the remaining 920 million go to find employment?” The post-pandemic unemployment rate in August was 8.3%. It has been worse very few times in the last 50 years. To be sure, jobless growth has been a structural weakness of our economy for decades but the missed opportunity is that India made self-inflicted, unforced errors in the last 10-12 years that flattened its growth trajectory.

In 2019, to nudge the private sector into investing, the government cut corporate tax rate to 22% for companies that do not avail any tax incentive. For new manufacturing companies, there was an even bigger tax cut, bringing it down to just 15%. The corporates, however, have not responded with investments so far, leaving the workforce-investment linkage broken as it is.

Industry data suggests that BSE 500 companies account for just 12% of the corporate investments in the country. The remaining companies, including non-BSE 500 and the unlisted/unregistered corporates account for 75% of corporate investments in the country or 38% of the total investments. Out of the total workforce of 460 million in India, the listed companies provide employment to just 7 million or about 2% of it.

Rathin Roy, managing director of ODI, a UK-based think tank, says, “There is no demand in the Indian economy and the corporates would not want to invest in expanding their capacities. The size of our middle class has already been exhausted and the corporates cannot grow by investing more. Unless the government incentivises production for those at the lower end of the economic chain, it would not make sense for corporates to invest in the economy.” In the fourth quarter of fiscal 2020-21, capacity utilisation stood at 69.9%, showing that Indian factories will need to use up excess capacity before thinking of new investments.

The post-mortem of this problem leads us back to the Great Financial Crisis of 2008. Successive attempts by the UPA government to pump money into the economy led to massive capacity expansion by the private sector. But demand did not match step with that, leading to the NPA crisis, making India Inc. forever shy of fresh investments. Net result: What started as an attempt to boost the economy and create jobs, ended up stretching banks and corporates with no gains in sight.

Size matters

Studies of Asian economies have pointed out how the average size of an Indian manufacturing company is small, making it uncompetitive in the global market. A study titled “The Distribution of Firm Size in India: What Can Survey Data Tell Us?” by Rana Hasan and Karl Robert L. Jandoc estimated that almost 85% of the Indian workforce in the manufacturing sector (or 37.5 million out of the total 44.6 million) were employed in enterprises with less than 50 employees. In China, this number was estimated to be just around 25%. The study emphasises how Indian policymakers failed to chart a growth path for small companies. And post-demonetisation India bears testimony to how most of them have now been killed. (See chart: Share of Manufacturing…)

“The condition of SMEs has been really bad over the past decade. If you look at India’s GDP growth, it does not take into account the data of Indian SMEs and informal sector companies. We assume that their performance is congruent with those in the formal sector. But post demonetisation and GST implementation, it has changed,” says Arun Kumar, Malcolm Adiseshiah Chair Professor at Institute of Social Sciences.

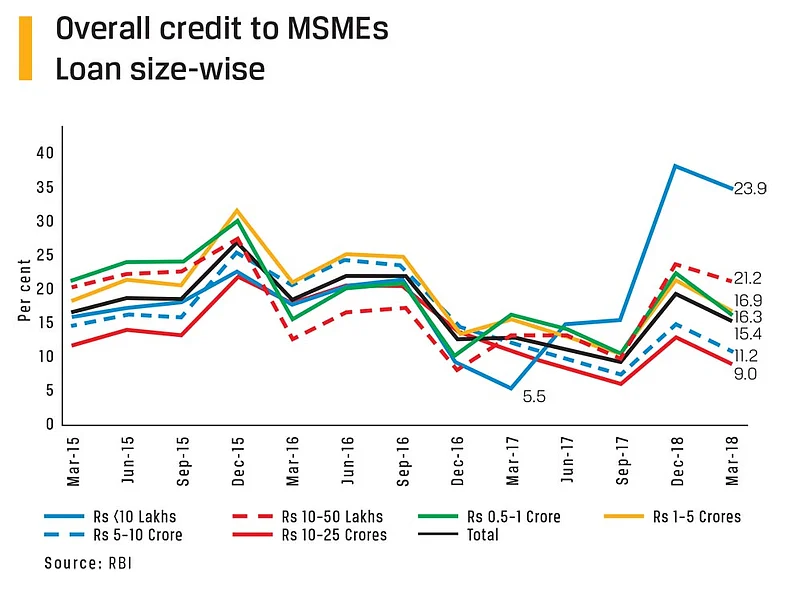

This is echoed by none other than the Reserve Bank of India. “The introduction of GST led to an increase in compliance costs and other operating costs for MSMEs as most of them were brought into the tax net,” reads a report titled ‘How have MSME Sector Credit and Exports Fared?’ by the central bank published in August 2017. Post demonetisation, the ticket size of loans to MSMEs came down drastically, it notes. Between December 2015 and March 2018, the percentage of loans in the Rs 10 million to Rs 50 million range nearly halved to 16% of the total loan book—from close to 30%. It clearly suggests that banks have been unwilling to give out large ticket size loans to MSMEs to expand their business. (See chart: Overall Credit…)

Agenda for the next decade

Where does India go from here, then? Can it make the 2020s a decade that steers the economy back to an average decadal growth of 8%? In the immediate term, the prospects are bleak, given how the economy has been battered by the pandemic. While India had expected to become a $5-trillion economy by 2024, given the current circumstances,

it looks impossible.

Deshpande from CRISIL believes that investment from the industry will decide how fast the Indian economy comes back on the growth trajectory. “Investment revival inarguably remains the single-biggest challenge. Investments have been trailing real GDP growth for several years now. The overall investment rate in the economy slipped from 34.3% of the real GDP in fiscal 2012 to 30.8% in fiscal 2017.” It touched a low of 27.1% in 2020-21, going by latest data available.

Recovery, she reckons, is still two to three years away. “Broadly, by fiscal 2023, with vaccinations becoming widely available and severe Covid-19 cases falling, the contact-based services will also open up and make recovery broad-based,” she says

Motilal Oswal’s Gupta, too, does not see any cues for robust growth in the coming few years. “The biggest challenge would be from the household sector because we have become too dependent on private consumption and they have been significantly hurt because of Covid-19. Their behaviour will determine how we grow in the current financial year. Over the next five to seven years, we will grow at 6-7%,” he adds. It doesn’t help that consumer inflation has been rising in recent months leaving less to spend on consumption.

Social scientists, economists as well as activists have, for long, pointed out the phenomenon of jobless growth in India over many years. The issue became the bone of contention in the Amartya Sen vs Jagdish Bhagwati debate of 2013. Sen, a Nobel laureate in economics, advocated that India should invest more in its social infrastructure like public hospitals and schools to boost productivity and this would lead to higher growth.

Bhagwati, another eminent economist, argued that high growth will generate resources that can then be invested in the social welfare of people. Unfortunately, the debate between the two stalwarts is wrongly seen as a debate between economic growth and wealth redistribution when the question to be asked is what happens when growth slows down. While it may be logical to think the surplus produced by a higher growth can be used to take more people out of poverty or push the lower middle class into the middle class, it does not answer how to get there.

R Gopalan, former secretary, Department of Economic Affairs in the Ministry of Finance, points out to more fundamental problems that need addressing: the problem of inequality and lack of services for the poor. “The divide between the rich and poor has been widening in India and without addressing this issue, it would not be possible to create a middle class that consumes goods and services in great quantities,” he says, listing skill development, income and job generation, and quality health and educational services for everyone as mechanisms to raise incomes. “Unless we address the rising inequality, fuelling demand would be impossible ,” he concludes.

True. As per data from 2017, India is second, only to Russia, when ranked by the Gini coefficient which measures inequality in income distribution. And it has been on the up: from 34.4% in 2014 to 47.9% in 2018. NGO Oxfam calculates it would take 941 years for a minimum wage worker in rural India to earn what the top paid executive at a leading garment manufacturer makes. Numbers suggest that the policymakers have followed the Bhagwati model over the years without seeking solutions to the concentration of wealth.

Another cause of worry is low female labour participation in India’s workforce, according to Gopalan. A World Bank study done recently points out that the female labour participation rate in India had fallen to 20.3% in 2019 from more than 26% in 2005 . That is lower than 30.5% in Bangladesh and 33.7% in Sri Lanka. One of the reasons Bangladesh has been able to surpass both India and Pakistan in GDP per capita income within a decade is its high female labour participation in the economy.

Taking a dig at Sen’s advocacy of redistribution economics, Bhagwati had said in 2013: “Sen puts the cart before the horse; and the cart is a dilapidated jalopy!” But, the reality of today’s India is that its roads of policy stay dilapidated on which neither Bhagwati’s horse nor Sen’s jalopy can run. And, who will know this better than Kumar and millions of his fellow Indians who are left standing by the road waiting for the apocryphal car to prosperity.

***

Look Back In Anger

Anil joined a private bank’s wealth management wing in Mumbai in a clerical post in 2006. By 2009, his colleagues advised him to take time off and pursue an MBA, after all he needed to push his career if he was to marry his officer girlfriend. He had saved up some money, and decided to quit his job, prepare for MBA schools, pursue the degree, and return to the job market in two years. Seldom does life pan out as planned. Anil completed his MBA but found no takers in 2011. Now, he was overqualified for his previous job. By 2012, he was ready to latch on to any opportunity that came his way. He remembered a school friend who had settled in China, married a local and was running an industrial adhesive manufacturing unit in Guangzhou. He had clients in India and promised Anil a commission if he managed to grab more business. Anil jumped at the opportunity, made a few trips to China, and bagged more clients around Delhi, Punjab and Maharashtra. Soon, Anil had rented a small office at Sakinaka in Mumbai and distributed the adhesive his friend manufactured in China. Suddenly, 2014, the taxman knocked at Anil’s doors. They alleged price arbitrage and raised a tax claim of Rs 40 lakh on him for importing adhesives from China at a lower price and selling them at a higher price in India. Seven years on, Anil is still fighting his tax case while his business has evaporated.

***

Death Of A Dream

32-year-old Dhritiman worked in the back office of a car showroom in Kolkata. He was responsible for drawing up the insurance policy every time a car was sold. The showroom was a 10-minute walk from his house and the work hours meant that he could also pursue his passion in theatre. Within a year at the showroom, he got called up to the company’s largest showroom in the city. Though an hour away from his house, he accepted the offer since his salary was being doubled. In the Kolkata of 2010s, Rs 10,000 a month was decent money. Though the next few years saw Dhritiman grow into a team leader managing the back-office team, his annual increments were not keeping pace with the high levels of inflation of 2013-14. He was looking to switch jobs to bump up his salary but he wasn’t successful. Then came demonetisation. And it only got worse seven months later as India adopted a new indirect tax regime. A higher rate of GST meant higher price of cars and the spike in fuel prices didn’t help either. The one-hour commute between his home and workplace, without the lure of a double-digit annual raise, was now bothering Dhritiman. By 2018, his situation had turned hopeless. Desperate for a change and better prospects, he decided to quit his job. His friend had bought a car, hired a driver, and listed it on the many ride-hailing apps in the city. Business was good, promised his friend. Dhritiman followed suit and by the end of 2019, business was indeed good. But he had not bargained for a once-in-a-century event like the pandemic to ravage his life. With extended lockdowns, his earnings from the car vanished. Everyone around assured him that once normal life resumed demand for taxis would be back in no time. But by August last year, the situation didn’t improve. While he got rid of his driver, he still had to pay EMIs on the car that remained parked in the rented garage. A year on, several attempts to sell the car have failed and he contemplated driving around himself. But middle-class values stopped him from taking up the job of a driver. A depressed Dhritiman hasn’t been keeping well lately. Doctors have advised psychiatric help, but his father’s pension cannot be used to pay EMIs as well as for expensive medicines and counselling. A listless Dhritiman mostly sits in his balcony overlooking the garage, lost in his thoughts about his days at the theatre. Even the back-office job at the showroom doesn’t seem so bad anymore.