Gautam Adani was the world’s third richest man in January. Having surpassed billionaires Jeff Bezos, Bill Gates and Mukesh Ambani in the world’s richest list, the chairman of the Adani group seemed unstoppable on the stock markets. But then, Hindenburg Research struck the group with its damning report, calling the rise of Adani as one of the biggest corporate cons in history. Within days stocks of Adani companies started crashing.

The US-based research firm alleged that the Adani group was involved in stock manipulation and misreporting financial parameters, which led to overvaluation of the group companies. The group also faced charges of conflict of interest on account of involvement of group promoter Gautam Adani’s brothers Rajesh and Vinod in bribery and tax-evasion cases. The report forced the company to stall its Rs 20,000 crore follow-on public offer despite it having been fully subscribed.

But this was not the end of the problem for the Adani group. Its companies now face scrutiny from environment, social and governance (ESG)-compliant funds and research firms that hold the power of grounding Gautam Adani’s green dreams, a business plan that was at the heart of India’s green transition over the next decade. It is important to note that every point raised by Hindenburg in its report against the Adani group is part of the ESG framework that has become the driving-point of investors in the West.

The ESG framework was derived around two decades back as a voluntary movement to reform Western capitalism, which faced criticism on account of destroying earth’s fragile ecosystem by promoting wasteful expenditure through consumerism. Investors across the world have come to terms with the need and value of the ESG framework, which requires them to think green and accountability while dreaming of money. As of March 2021, the collective assets under management (AuM) represented by the 3,826 PRI signatories stood at $121 trillion. On the ESG front, a report by global consultancy firm PwC expects the AuM to reach $33.9 trillion by 2026, as compared to $18.4 trillion in 2021. “ESG assets are on pace to constitute 21.5% of total global AuM in less than 5 years,” reads the report. To put things in perspective, the AuM in the Indian mutual funds industry as of February 2023 was just $490 billion.

Sword of Damocles

Any company looking to raise money from global investors needs to be ESG compliant, as every significant international institutional investor is looking to assess the ESG score of the potential investee.

Though reluctantly, the Indian government has fallen in line over the years, coming up with rules that nudge companies to be ESG compliant. In 2009, the Ministry of Corporate Affairs issued the National Voluntary Guidelines (NVGs) on corporate social responsibility. In 2012, the Securities and Exchange Board of India (SEBI) asked the top 100 listed companies by market capitalisation to start filing business responsibility reports under the NVGs. In 2015 and 2019, the mandate was extended to 500 and 1,000 listed companies respectively. In 2021, SEBI proposed guidelines for the mutual fund industry, asking ESG-based funds to keep 80% of their assets in securities that follow the sustainability theme. In the same year, SEBI also developed the new, more comprehensive concept of reporting in the form of business responsibility and sustainability reports (BRSRs).

With global climate negotiations having reached their zenith at the COP26 summit, forcing countries like India to commit to define net-zero emission targets, there is a sword hanging over India Inc. that can finish a company’s business prospects in no time, and Adani is just a trailer of the horror movie that Indian businesses would not enjoy watching in the coming years.

Problem of the Pyramid

The “E” and the “S” of the “ESG” are more metrics-driven whose performance indicators are better established, which makes disclosures relatively straightforward, observes Dipankar Ghosh, partner at BDO India—a global network of finance professionals and organisations. “[However] there are sharp sensitivities around the ‘G’, especially when it is related to internal barriers for good governance, often leading to denial,” he adds, speaking in the context of corporate governance which is often identified as the Achilles heel of India Inc.

Many call it the Indian way of doing business where corporate governance has been abandoned at the altar of complex, and often opaque, subsidiary structures of companies, concentration of promoter ownership and instances of questionable related-party transactions. Without meeting governance standards, no corporate ESG regime can be complete, making companies untouchable to foreign investors, the case in point being the Adani group.

Beyond the top lot of the listed Indian companies, there is a serious problem with understanding and documenting the ESG frameworks within organisational structures and processes. “It will be easy for the top 200 companies to file BRSRs, as they have the money and the expertise to do it. But I do not think that the bottom 200 companies will find it easy to do so. The BRSR format is comprehensive and prohibitively expensive to implement. A large number of Indian companies will find it difficult to collect the actionable data on the ESG compliance,” says Praveen Garg, senior advisor, ESG and climate change, at the National Productivity Council. He has overseen the evolution of India’s ESG regulation mechanism as a joint secretary in the ministries of finance and environment. “We need to have something called ‘BRSR lite’ for companies at the bottom of the pyramid. Otherwise, corporates will struggle to report [ESG compliance]. They may also end up facing penalties for misreporting in the future,” Garg adds.

The government has been trying to reform India Inc’s work culture and business ethics. However, despite years of efforts, things have not moved very far. For example, the last decade was marred by corporate governance issues in the banking system. Now, there is trouble brewing in India’s tech start-up ecosystem, with founders facing allegations of siphoning off millions of dollars of venture capital firms and retails investors.

One of the criticism India’s tech ecosystem faces on corporate governance is its preference of valuation over profitability of the business. Indian start-up founders on the other hand have accused global investors of putting pressure on them to grow the business at any cost, leading to lapses in corporate governance. The issue of Bharat Pe founder Ashneer Grover accusing US-based venture capital firm Sequoia—which exited the India market after a spate of corporate governance-related controversies hit the funds’ portfolio firms—of using unfair means to remove him from the company’s board, was the talk of the town.

While SEBI had made changes in 2021 to its listing norms to allow loss-making tech firms to raise money from the capital market, the rule led to massive loss of investor wealth. Most tech firms that got listed on the bourses led to erosion of investor wealth. Many experts raised questions over the market regulator’s decision to allow companies to list without ensuring corporate governance compliance by VC-funded companies. But others differ.

Prasanna Rao, co-founder and CEO at Arya.ag, a grain commerce platform, does not consider SEBI’s decision immature or taken under pressure. “We have seen multiple start-ups around the world list and generate handsome returns for investors. This has provided good companies an avenue to reach out to investors. Having said so, the founders and companies have to be responsible in carefully arriving at the valuation of their enterprises,” he says.

Geoeconomics of ESG Regime

The war in Ukraine has changed the way major global power blocks deal with each other politically and economically. A sense of protectionism is palpable even among the proponents of globalisation, and the global ESG regime is under pressure to accommodate these trends. The US and the European Union have created non-trade barriers that are likely to make it difficult for other countries to do business in their regions on fair terms.

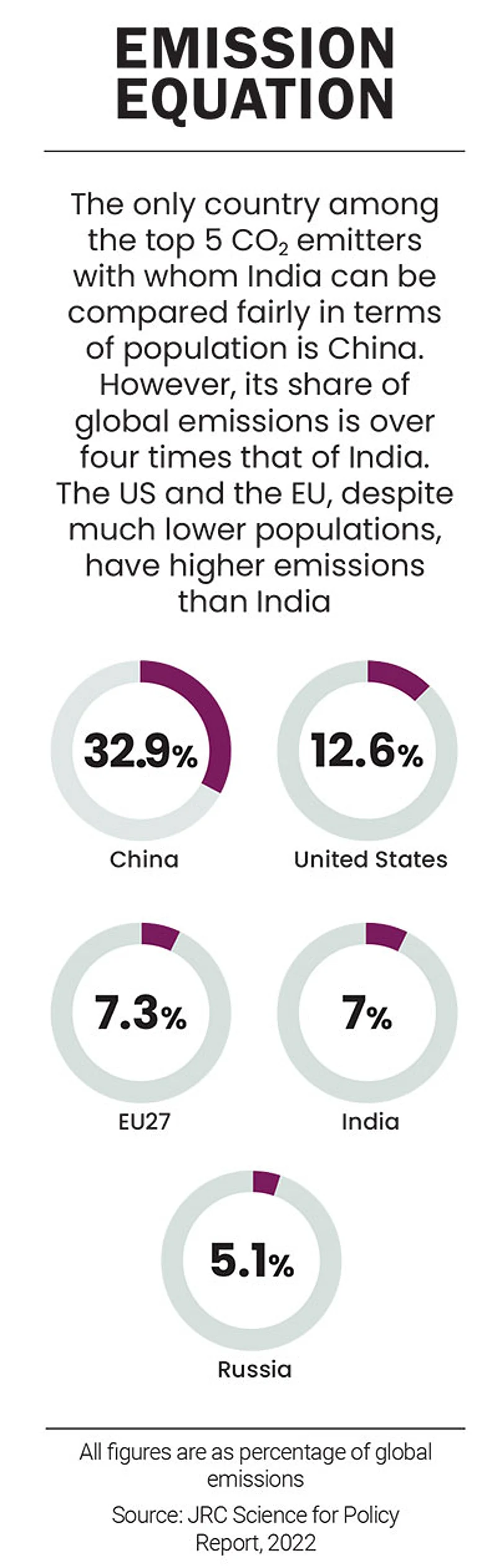

The European Union’s Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM) has sent ripples among developing nations like India, Brazil and South Africa. The CBAM seeks to impose penalties on companies that cannot substantiate the carbon emission cuts of the level achieved by European producers. This means that if an Indian cement or steel firm has a larger carbon footprint than a European steel maker, the importer of Indian steel will have to pay a penalty for purchasing it, rendering it less competitive.

“India has a target of becoming carbon neutral by 2070, while the European Union’s target is 2050. Why should an Indian company be penalised for not meeting the standards of a European company?” asks Sheshagiri Rao, joint managing director and group CFO of JSW Steel.

The US has a more potent protectionist tool in the form of the Inflation Reduction Act, which makes way for heavy subsidies to local industries in the name of fighting inflation and climate change. The act has provisions for giving special treatment to local manufacturers and countries with friendly free trade agreements. India’s choice to remain neutral in the Russia-Ukraine war could cost its companies heavily if they do not get preference for supplying products to the US government-funded projects.

“Indian companies will have to deploy a huge amount of capital to expand their export capacity on the terms and conditions set by Western countries. They gave subsidies to developing countries for adopting green technologies, but that has been insufficient. The transition of India Inc. will become very difficult unless, as a nation, we are able to negotiate a good deal on these fronts,” says Rao.

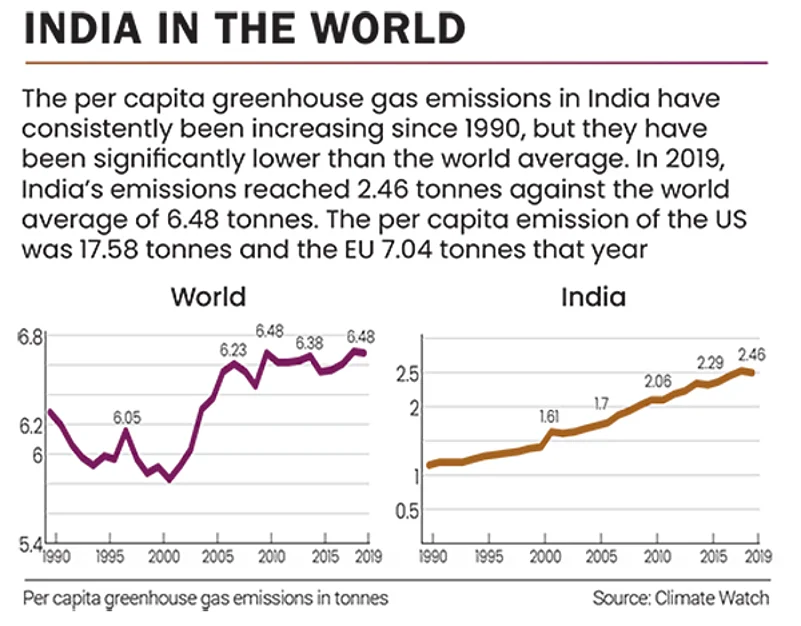

If the mighty like the Adani group can fall, other Indian companies should take note with immediate effect. Home to 1.4 billion people in the world, India has a long way to go before providing an above-subsistence-level lifestyle to a large size of its population. The country, despite having the coveted tag of being the fastest growing major economy of the world, lags on most human development indices. Developed nations’ belief in sustainable growth comes after centuries of unsustainable growth strategy that helped them accumulate wealth needed for this philosophy. The amount of subsidies their governments are deploying to turn industries green is unprecedented.

For India Inc., the situation is starkly opposite. While the Centre is trying to adopt an international ESG reporting framework for domestic consumption, though without an ability to subsidise it, we may have to settle with humble growth targets or meet the fate of Adani’s green dreams.

With input from Vinita Bhatia