When Union transport minister Nitin Gadkari rode in the hydrogen-powered Toyota Mirai car to Parliament last month, it shocked not just the Parliamentarians around but also Indian automakers. Till a few years ago, electric vehicles used to be at the centre of every discussion around the clean technology of the future. With the government’s push to wean out internal combustion engines, the incentives and attraction for the lithium-ion-battery-powered engines had captured the imagination of automakers.

Over the years, with the help of government incentives, Tata, Hyundai, Hero and Bajaj, among others, have invested billions of dollars in getting the EV technology right, albeit with many hiccups.

But, here was Gadkari, emerging from a world-class car, which is built on a technology that Indian carmakers have little idea about.

Beleaguered Automakers

Indian automakers have incurred substantial loss of revenue in the last decade due to changing emission regulations that have put additional pressure on their balance sheets. Even before the industry could recover from the cost of jumping from Bharat Stage IV to Bharat Stage VI standards, it was asked to move towards EVs in order to help India meet its emission-cut targets under the international climate change negotiations.

But now, with the emergence of another clean technology, which appears to be cleaner than the electric cars powered by lithium-ion batteries, they fear the pressure of incurring losses on the investments made on the EV technology. “OEMs will face this dilemma of choosing between multiple technologies that are emerging in the markets. They will have to make their bets and hope to recover their cost by selling vehicles based on those technologies in the market. If a company fails to get its technology right, it will face existential crisis,” said Gaurav Vangaal, associate director, IHS Markit.

Interestingly, India is expected to register one million sales of EVs in 2022, which is equal to the total EVs sold in the last 15 years. It has taken billions of dollars’ worth of investments from the government as well as the industry for the Indian car market to reach here. There is a long way to go before the Indian automobile industry starts recovering its investments made in the EV segment. While the Centre announced a production-linked incentive scheme in September 2021, which promises incentives worth Rs 26,058 crore to the industry for investing in EVs and hydrogen fuel-cell technology, it will be difficult to convince the companies that have already taken a leap in EV technology to divert a part of their R&D towards hydrogen fuel-cell vehicles.

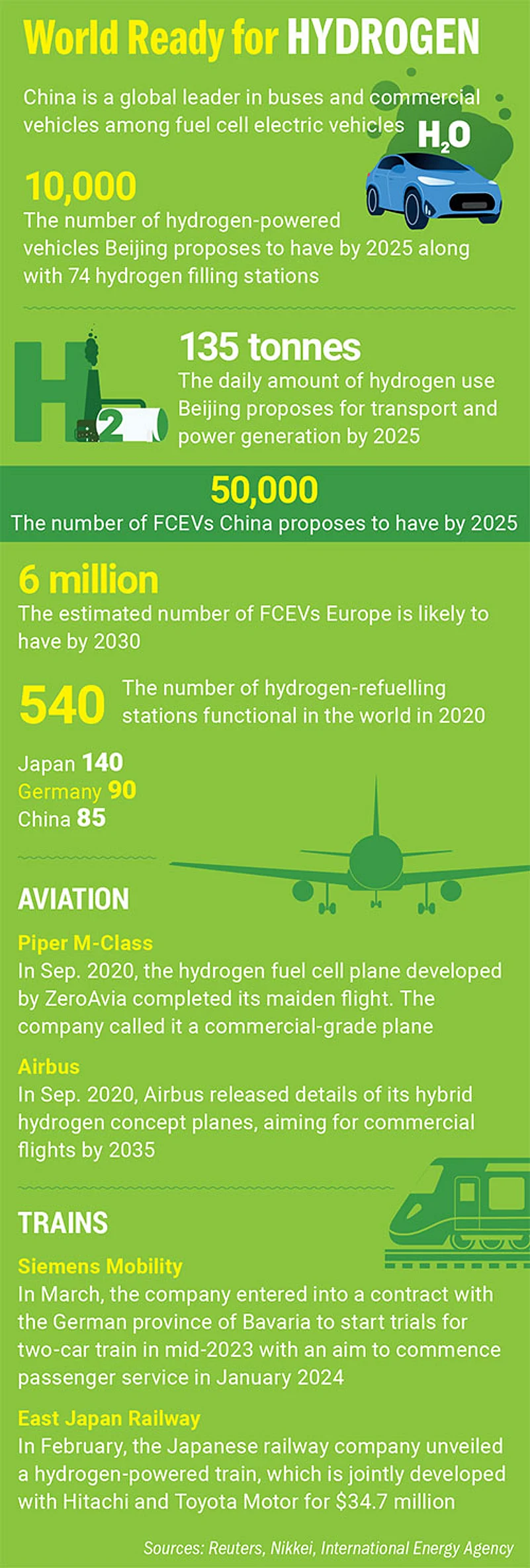

Hydrogen-powered cars, also known as fuel cell electric vehicles (FCEVs), are beginning to take off. According to the International Energy Agency, “global FCEV deployment has been concentrated largely on passenger light-duty vehicles, which accounted for three-quarters of FCEV stock at the end of 2020, with buses making up ~15% and commercial vehicles meeting the remaining 10%”. However, this experience differs across continents. While the observation is true for the US and Japan, China has adopted FCEV policies for medium and heavy commercial vehicles.

Experts in India tend to side with the Chinese example. “Green hydrogen will be useful wherever renewable electricity is not a substitute for fossil fuels. For shipping, aviation, long-distance heavy-duty trucks, manufacturing of fertilisers, cement and steel, it can be the substitute for fossil fuels and the way to net zero. But, for railways, automobiles and other sectors that can be run on electricity, we do not need it,” says Ajay Shankar, a former secretary to the government of India and distinguished fellow at The Energy and Resources Institute.