When some of the iconic car manufacturers announce that they are going to overhaul their fleet, you must take notice. Over the past few months, American and European giants such as General Motors, Ford, Audi and Volkswagen have announced plans to phase out manufacturing of diesel and petrol-powered cars, and send out only electric vehicles over the next decade and a half. Granted, Ford and Volkswagen will cover only the European market initially. At the other end of the world, Japanese automaker Honda has set itself a deadline of 2040.

In contrast, the wheels are turning slowly in India.

There is a buzz all right with Tesla announcing its much-anticipated entry into the market. Top luxury players, including Mercedes Benz, Jaguar and Volvo, have introduced their all-electric variants in the country in a span of one year, and Audi is set to launch its variant soon. Traditional names such as Tata Motors and Mahindra have rolled out their wheels and captured a significant share of the small market. On its part, the government had announced tax cuts and rebates in the FY22 Budget — it slashed the GST on EVs to 5% and announced an income tax exemption of up to Rs.150,000 on interest payments for loans to buy EVs.

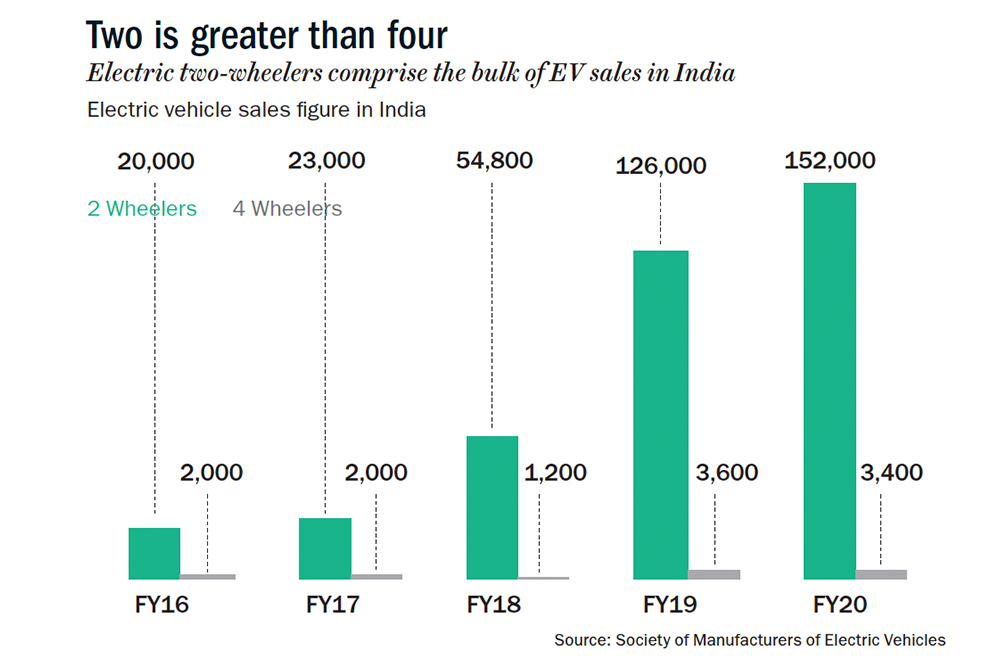

But the response from customers has been lukewarm. In India’s EV landscape, two-wheelers are the most popular (see: Two is greater than four). In FY21, a total of 236,802 units of EVs were sold, according to the Society of Manufacturers of Electric Vehicles. Out of this, only 1.9% was four-wheelers.

“The West is a car-centric market,” says Shashidhar KJ, an associate technology fellow at the Observer Research Foundation, “In India, people are more comfortable with two-wheelers… Four-wheelers are also used for intercity travel and stopping to charge midway could be a hassle. You don’t know if you will find charging stations or how many hours it will take for the battery to be fully charged.”

The trend is unlikely to change. A recent BloombergNEF report has shown that only 8% of the new car sales in the country will be electric by 2030 as against the 28% globally. Meanwhile, credit rating agencies CRISIL and ICRA expect the overall EV penetration in the passenger vehicle market to remain at only around 5% by 2025.

While the tax sweeteners extended to customers have been received with little more than a yawn, the subsidies and incentives to encourage manufacturers are likely to benefit two-wheelers more. For one, two-wheelers are the biggest beneficiary of the Rs. 100-billion subsidy earmarked for the FAME-II scheme which offers a demand subsidy (basically a subsidy offered to drive up demand) of Rs. 15,000 per kilowatt hour (kWh) on electric bikes and scooters in India. It has allowed electric scooter manufacturers such as Ather Energy to slash the prices of its models by as much as Rs. 14,500. The FAME India scheme, or the scheme to drive Faster Adoption and Manufacturing of (Strong) Hybrid and Electric Vehicles in India, was first introduced in 2015 and its second phase, or FAME-II, began in 2019.

There is also the production-linked incentive scheme (PLIS) with a budget of Rs. 181 billion to promote production of advanced chemistry cells (ACCs) or batteries which power EVs. But this, too, is likely to rev up the two-wheeler industry more. While the scheme is meant to promote the sector in general, it will make more economic sense for two-wheeler manufacturers. This is because, to avail the benefits of the scheme, a manufacturer has to invest significantly and do a lot of value addition locally—the unit will have to have a minimum capacity of 5GWh and the domestic value addition will need to touch 60% in five years. Only two-wheelers see the demand that justifies this kind of commitment.

Plug in to value

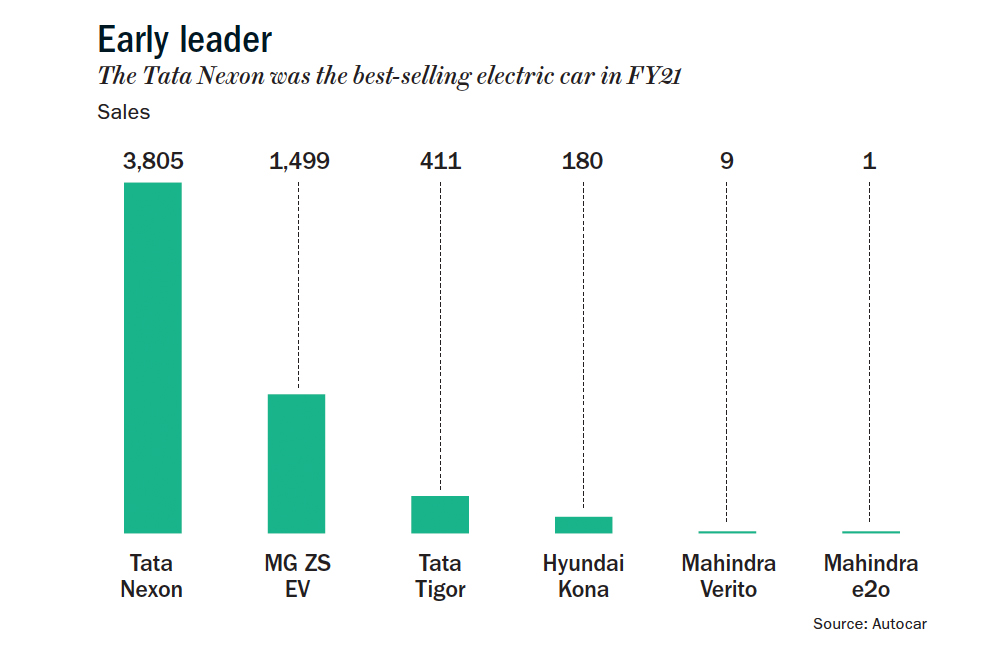

To drive demand in the Indian car market, the models have to be affordable. As of now, only Tata Motors has a model that has been priced low for an EV car (an Autocar review noted that it undercuts other EVs such as Hyundai’s Kona and MG ZS by Rs. 700,000). Priced between Rs. 1.4 million and Rs. 1.6 million, the Nexon EV has 64% of the EV car market (see: Early leader). This model is what led to the three-fold increase in the company’s EV sales last year. While the car does not fall under the affordable passenger car category, analysts say that Nexon is rightly priced and that it offers value for money. Otherwise, as most of the electric cars are either SUVs or sedans, the sales have been dismal.

Nexon maintains a precarious balance. With a battery capacity of 30.2 kWh, it runs 312 kilometres on a single charge. In comparison, the Tesla Model 3’s 54-kwh battery gives 560 km on a single charge. The Tesla model will go on sale in India by the end of this calendar. If Nexon wants to up its game and increase its battery capacity to 40 kWh, its price will shoot up by Rs. 250,000 at least, according to analysts. As of now, Tata is letting the balance tilt in favour of affordability.

Tata is also trying to build an ecosystem for EVs with the support of group companies. Tata Power, for instance, is helping set up charging infrastructure across cities and Tata Chemicals is evaluating technical partners for establishing a lithium-ion battery manufacturing plant.

While Tata is ahead of all others, it was Mahindra and Mahindra who was the first Indian auto major to buy into the electric car story. In 2010, it bought the Reva Electric Car Company and renamed it Mahindra Reva Electric Vehicles. Two years later, it launched its first EV model ‘e2o’.

However, since then, Mahindra’s ride in the electric car space has been bumpy. The end of the road for e2o came in 2019, when Mahindra discontinued its production for the domestic market. The company has not produced a single EV four-wheeler so far in 2021. The only electric sedan currently being sold by M&M, the eVerito, has not been rolled out of the production lines since December last year.

Mahindra’s lack of success in the electric car space mirrors the lacklustre performance of its overall offering in diesel cars, says Basudeb Banerjee, research analyst at Ambit Capital.

“Over the last 3-5 years, Mahindra has lost market share in the space of diesel cars as their models have failed to appeal to the younger generation. Their electric cars are mostly a variant of the existing models. When the models are not successful in the diesel space itself, how can one expect them to succeed in the electric space?” asks Banerjee.

However, Mahindra is reluctant to exit a segment they moved into before anyone else and is still bullish on its prospects. For now, the company wants to put 500,000 EVs on Indian roads by 2025, and has invested Rs. 17 billion in its EV business in the country and another Rs. 5 billion in an R&D centre. This April, the company said that it will put Rs. 30 billion more into growing its EV business. Even with all this enthusiasm, they aren’t too keen on four-wheelers. They are more focused on three-wheelers and vans, saying four-wheelers are going to take a long time to give returns and the necessary infrastructure is not going to come up until the cost of ownership of an EV and an internal combustion engine (ICE) vehicle is going to be roughly the same. For that to happen, they see a horizon of three to five years at least. Meanwhile, Banerjee says that the focus of the capital allocation should be on coming up with good design capabilities and localised production of components to bring down costs.

Meanwhile, the country’s top two carmakers, Maruti Suzuki and Hyundai India, have shied away from betting big on electric. Maruti, which is yet to launch an electric car in the market, seems to be taking a wait-and-watch approach. In a conference call, the management said that localisation of parts is essential and that they are working on it. The minute it becomes viable to scale it up, they will.

There is a shortage of domestic production of batteries and this is a headache for carmakers. But to increase battery production, it should make business sense for battery manufacturers, who also include carmakers. That is, there should be demand. It is a chicken-and-egg situation. “For four-wheelers, the viability simply does not exist right now as the numbers are not there”, says Darshak Parikh, senior research analyst for electric mobility at IHS Markit. He adds that with the capex for the production of battery cells being significant, the initial push must come from the government or established automobile players looking for market share in the EV segment.

Otherwise, to make local production of parts viable, EV adoption has to increase. For this to happen, three things have to be addressed.

“One, the current battery technology does make the cost of acquisition of EV vehicles very high. Cost of the battery, as you know, is almost 50% of the cost of the EV vehicle. Second, the infrastructure for charging in our country is really small and maybe requires a lot of development before this adoption happens in a big way. And third is on the consumer part, our research shows there is a high amount of range anxiety. That is how many kilometers the car will go on a single charge,” said Shashank Srivastava, head of marketing & sales at Maruti Suzuki India, in the conference call.

Range anxiety remains a key concern for consumers. Electric variants of models typically provide a smaller range than their ICE models, while being priced higher. Tata Nexon’s petrol and diesel models, for instance, have a range of 765 kilometres against the 312 kilometres provided by its electric variant.

Maruti believes that electrification in India will be led by the hybrids. That the customers are likely to buy a hybrid or a model that runs on alternative fuels like CNG first, and then transition to an EV. Therefore, they have been asking the government to continue supporting hybrid vehicles. Consumers seem to believe the same. According to a recent global survey conducted by Deloitte, 24% of Indians prefer a hybrid as their next vehicle while merely 4% prefer a pure EV. However, government schemes such as FAME have centred their subsidy push on the latter. For its part, Maruti has launched hybrid versions of several of their top-selling models, including Ertiga, Brezza, Ciaz and Baleno.

While Maruti is kind of looking at EV cars, Hyundai has a dismal sales outlook for the category, expecting actual sales of EVs to be less than 1% of overall car sales by 2024.

If the domestic situation is so gloomy, can exports help? Analysts believe that it seems far-fetched at this point as Indian carmakers still struggle to compete with global players such as GM, Ford, Tesla and NIO in terms of design capabilities and battery capacities. The slow progress in investment in battery production technologies is also a deterrent. However, biggies like Reliance are trying to change that. The conglomerate has announced that it will start making advanced energy storage batteries and hydrogen fuel cells as part of its Rs. 750 billion investment in ‘new energy’. Ajay Srinivasan, director at CRISIL Research, says that such large-scale investments in energy storage solutions can help bridge the acquisition costs between EV and ICE vehicles. That said, since India is dependent on imports for raw materials for the latest batteries or the lithium nickel manganese cobalt oxides or Li-NMC batteries, the international prices of the materials will be crucial, too.

“In addition, the benefits of investment in local energy storage solutions will only accrue over the mid-term as the solution provider gains economies of scale,” he says. “Current lower levels of EV penetration across vehicle segments have been one of the key deterrents for large battery manufacturers such as LG Chem, CATL and so on for making investments in markets like India,” Srinivasan adds.

Again, chicken and egg. Which needs to come first? EV penetration or domestic production of parts that can drive down costs and increase EV penetration?

To compete in the global market, Indian products also need to catch up technologically. “We are still using technology the world has moved past”, Parikh says.

Although globally, for production of battery electric vehicles or BEVs, Li-Ion NMC cells are more in demand, in India, we favour lithium iron phosphate (LFP) cells, he adds. LFP cells have higher thermal stability, lower cost, and a longer cycle life but it has lower energy density. Therefore, it holds lesser energy per kilogram of its weight. Therefore, to increase its running time, a manufacturer will have to increase its weight. It either won’t be able to power a vehicle for long or it will add to the weight of the vehicle.

The Indian market is expected to transition to NMC batteries by 2026.

Even that year, the global average in battery power is expected to be 65kWh, which will be way higher than India’s, which will fall between 35 kWh and 40 kWh, according to IHS Markit.

Does it matter? Yes, because it will mean higher reliance on the public charging infrastructure, which, honestly, does not inspire confidence. India needs about 400,000 charging stations to meet the requirement for two million EVs that could run on its roads by 2026, according to a Grant Thornton-FICCI report. There were only 1,800 charging stations in India as of March 2021. Even these are tilted in favour of two-wheelers. The charging stations set up for two-wheelers cannot be used for four-wheelers because of the huge difference in the power and voltage requirements. While a typical electric two-wheeler has an average battery capacity of about 2 kWh and an input voltage of 72 volts, for four-wheelers, it stands at 30 kWh and 400 volts, respectively.

The verdict is clear. Globally, there is a flurry around EV cars, but in India, you can almost hear the crickets chirp. Leading players here are cautious and are likely to remain so for a while.