Rajkumar,* 29, belongs to the Basti district of Uttar Pradesh. He works with Meher Auto Parts Industries situated in the Pawar Vasti area of Pune. He shudders in fear when he recalls December 11, 2022, the day on which he lost three fingers while working in the factory. “It was 8 am. I was sitting on a supply line. Suddenly, my hand came under a power press machine and I lost three fingers. There were no sensors for the pressing machines, otherwise this tragedy could have been averted,” he says. Rajkumar is not the only one who has met with such an accident at the worksite.

Ramesh Singh,* 36, has been working in Pune’s auto sector since 2016. His hand came under power press machine on August 20, 2022. “None of the sensors was operational. I lost four fingers of a hand in the accident,” Singh recalls. He grumbles about inadequate labour-safety standards being followed in small and medium enterprises in various parts of the country.

These two industrial accidents point to a darker side of informal factories mushrooming in India.

According to a report titled Crushed prepared by the Safe in India Foundation, a Manesar-based organisation that works for industrial workers, over 50% of injuries brought to its notice occur on dangerous power press machines. On an average, the number of fingers lost on a power press machine is 2.3 per incident. Other machines on which accidents happen include moulding, drilling, cutting, die casting and crane machines. “The absence of safety sensors and/or other safety mechanisms is the biggest reason for such accidents. This is followed by the incidence of malfunctioning machines. Majority of power press injuries happen because of a lack of safety sensors,” Sandeep Sachdeva, co-founder of the foundation, says. “Occupational safety in India is good in the top few companies, but it gets worse down the pyramid in supply chain companies. In our experience, in 90% cases, either there were no sensors [for the power press machines] or they malfunctioned,” he adds.

Post Hoc Realisation

But it is not only industrial injuries that have caused a grave concern among stakeholders. In fact, industrial deaths owing to safety lapses at factories are far more alarming, and, together, they point to a serious violation of India’s factory and labour laws.

Komal,* 21, a resident of Mundka in western Delhi, remembers the horrific day when many of her colleagues succumbed to a deadly fire in the four-storey building of Cofe Impex Pvt. Ltd, a manufacturing unit of electronics equipment located in Mundka, where they worked. “I was rescued with a rope. My hands and legs were burnt during the process,” she says.

The fire which was triggered by short circuit on May 13, 2022, caused the death of 27 labourers, as per the official data. In an enquiry commissioned by the Municipal Corporation of Delhi (MCD), it was found that the factory was operating in the extended lal dora area of Mundka village. “This violated the rule which does not allow factories to operate in lal dora areas. Also, the factory was operating in complete violation of all labour laws and safety regulations, operating without no-objection certificate from the fire department,” the fact-finding report of the MCD says.

The part of village land that incorporates the village habitation, referred to as abadi, is known as the lal dora—which literally means red tape—land or property.

“There were no fire extinguishers or safety measures installed for labourers in the factory. In fact, there was no emergency exit in the premises,” Komal recalls. The Factories Act mandates at least two emergency exits in each room.

L.R.K. Krishnan, a professor at VIT Business School, Chennai, who studies labour issues in the manufacturing sector, says, “Industrial accidents have claimed over 6,300 lives between 2014 and 2017, out of which 2,759 lives were lost while operating machinery (4,222 incidents); 1,017 deaths were lost in general industrial accidents (1,363 incidents); 956 people lost lives in fire-cracker/match-box manufacturing (882 incidents); 732 deaths took place due to fire in mines (83 incidents); 542 lives were lost in industrial boiler/cylinder explosion (167 incidents); 274 deaths were reported during mining disasters (549 incidents); and, 84 people lost lives due to fire in other types of factories (741 incidents).”

In February, the National Human Rights Commission (NHRC) took suo motu cognizance of a newspaper article which quoted data from the Ministry of Labour and Employment’s Directorate General Factory Advice Service and Labour Institutes (DGFASLI), claiming that three people died and 11 were injured each day on an average between 2017 and 2022 due to accidents taking place in registered factories. The NHRC sent notices to the Centre, states and Union territories over the reported high death rate of workers and asked for the details of measures taken for ensuring the protection of workers’ rights.

Dharmendra Kumar, national secretary of the Working People’s Coalition, a network of organisations that work for workers in the informal sector and which conducted a fact-finding study of the Mundka fire accident, says, “Now, a lot of factories which have not been formally approved have mushroomed not only in Delhi but all over India. This is because of a lack of provisioning of land, which leads to informal and not formally approved factories in lal dora areas where regulation is more relaxed and taxation is liberal.”

Education of workers and a lack of training in handling types of machinery are also dubbed by experts as key reasons for the accidents taking place in factories. According to the Safe in India Foundation, the Automotive Skills Development Council has mandated that press shop assistants and operators need a minimum education of up to Class VIII and a prerequisite licence or training in basic press shop housekeeping skills and safety. Its report found that helpers with little or no training are regularly appointed at these factories. Consequently, the representation of helpers among those injured is high. The report also found that these workers are overworked and denied extra wages for overtime work. Nearly 51% of workers that the report covered reported operating in 12-hour shifts, which also contributes to accidents.

When Government Underreports

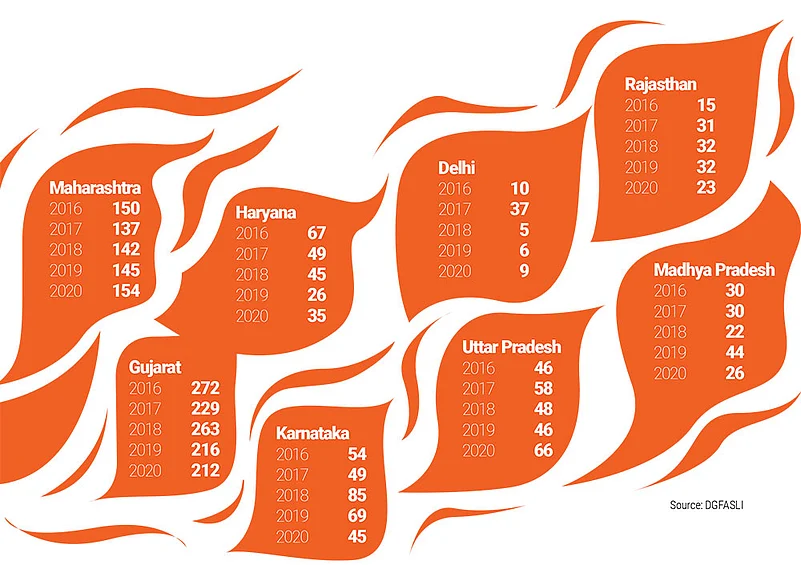

Dharmendra Kumar claims that the fact-finding team found that over 70 people had died in the Mundka fire; however, the official data puts this figure at 27. Similarly, he says, in the case of industrial injuries, states and the government report far fewer accidents in comparison to what unfolds on the ground. Sachdeva of the Safe in India Foundation concurs with Kumar, saying, “In our study, we spotted over 1,000 cases of industrial injuries in a year only in Haryana, but the state government reports only 50 cases of industrial injury annually. The official reporting stands at just 5% of the truth.”

Similarly, the DGFASLI has been reporting a reducing number of non-fatal accidents in Maharashtra. The Safe in India Foundation does not have trend data in Maharashtra yet, but in a span of about two months, it has identified 93 industrial accidents in the auto sector in Pune and expects that the figure of injured workers in Pune alone could touch 500 per annum.

The Factories Act, 1948, requires all factories that use electricity and employ more than 10 workers to be registered under the act (this threshold has been increased to 20 workers in the Occupational Safety, Health and Working Conditions (OSHWC) Code, thereby diluting the effectiveness of the Factories Act further on smaller factories). Such registered factories are required to send a notice of any accident if the resulting injury prevents the injured person from working for more than 48 hours to the state industrial safety and health department, according to Clause 88 of the Factories Act. In the backdrop of provisions like compensation and healthcare for the injured, there is non-reporting by employers. According to experts, this lacuna and contractualisation of workers is giving way to this phenomenon, and that is why they take the government data with a pinch of salt.

An Inadequate System

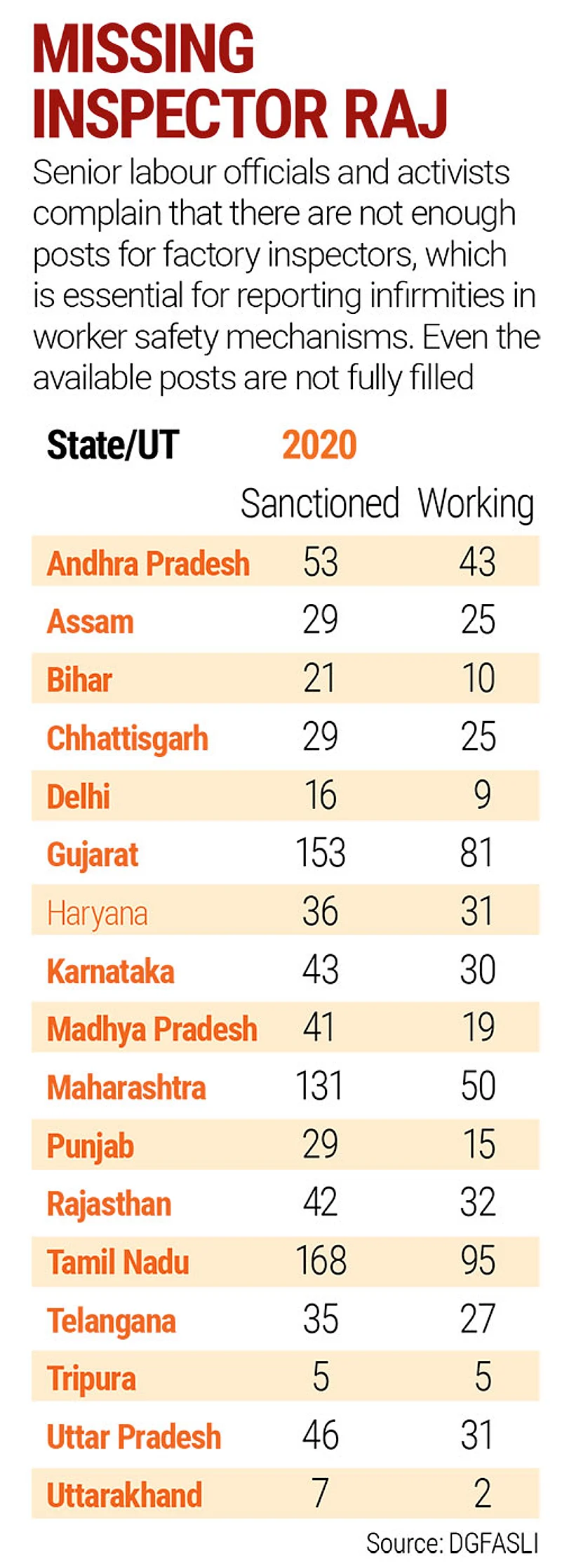

According to Section 9 of the Factories Act, factory inspectors are appointed to examine the premises, plant, machinery and other articles. They are also tasked with enquiring into any accident or dangerous occurrence, whether resulting in bodily injury and disability or not. According to the DGFASLI data, out of 1,040 sanctioned positions of factory inspectors, only 721 are currently operational. Even an industrialised state like Maharashtra lags on this count. “We have 105 positions for factory inspectors but only 30 officers in the role. A lack of human resource makes it difficult for us to carry out the inspection work,” Mukesh Patil, director of industrial safety, Maharashtra, tells Outlook Business.

The problem of shortfall in inspection incidents has persisted over the decades. “Till 2020, out of 37,000 registered factories, we were able to do an inspection of only 15,000 factories,” a retired official from Maharashtra says on the condition of anonymity. Similarly in Bihar, out of 19 sanctioned positions of factory inspector, only nine are deployed as of now.

“Usually, during factory inspections or when there is a fatal accident, the factory inspector visits the site and files remarks or a report that requires compliance. The factory management submits an action taken report a few months later, but then there is no follow-up done by the inspector to check whether the recommended changes have been made on the ground,” a former director of industrial safety in the Maharashtra government says while staying anonymous.

“These illegal factories, especially in lal dora areas, come to limelight only when any fire accident takes place. These factories typically deploy 10 to 12 workers,” S. Pandia Rajan, director, industrial safety and health, Labour Department of the Delhi government, says. “Another problem, obviously, is the shortage of factory inspectors. According to the norms, there should be one factory inspector for every 250 factories, but we have four factory inspectors for around 8,000 factories,” he adds.

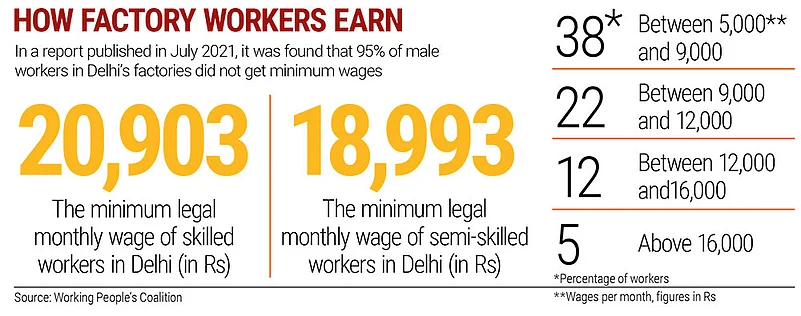

It is not just the accidents and injuries that are a cause of concern in India’s factories. Rather, being paid below the minimum wages which are set by Parliament and state legislations and not having any social security net for workers are big problems in themselves. According to a study on minimum wages conducted by the Working People’s Coalition, noncompliance to the laws on minimum wages is a key feature in the Indian labour market, with noncompliance rate hitting as high as 90% for some categories of workers. For instance, noncompliance to laws is higher in the cases of casual, female and unskilled workers and migrants. The network claims that informal workers and migrants receive even less than the minimum threshold that is needed to lead a decent life.

The contractualisation of employment has made it difficult for workers to have minimum wages.

The Working People’s Coalition has analysed the wage scenario for male workers in Delhi. In a July 2021 report, it notes that 38% of them earn between Rs 5,000 and Rs 9,000, 22% earn between Rs 9,000 and Rs 12,000 and 12% earn between Rs 12,000 and Rs 16,000. Only 5% of workers it studied received stipulated minimum wages, and 95% of all workers are compelled to accept the wages offered by their employers irrespective of what regulatory bodies proclaim.

Dark Future

Based on the recommendations made by the Second National Labour Commission, the government created four labour codes, including the Code on Wages, 2019, the Industrial Relations Code, 2020, the Code on Social Security, 2020, and the OSHWC Code, 2020. These codes subsumed 44 existing labour-related laws.

“The consolidation of labour laws helped in compliance and the standardisation of definitions. It also helped in removing conflicts among various statutes. With respect to employers, the cost of compliance and the problems of managing multiple registrations and licences have reduced. Moreover, a single window for filing returns is helping employers,” VIT Business School’s Krishnan says. He adds that digital modes of payments and web-based inspection procedures have made things easier for factory owners.

However, experts and activists have their fair share of concerns. Sachdeva believes that the new labour codes make room for the dilution of enforceable provisions. “For instance, the OSHWC Code, 2020, applies only to establishments that have more than 20 workers if they have an official power connection and more than 40 if they do not have the power aid supply. This was 10 and 20 respectively in earlier laws. In the case of contractual workers, the minimum threshold was 20 for establishments to be covered under the Factories Act, which have now been raised to 50 in the OSHWC Code. This increase will allow more units to operate outside the legal purview,” he explains.

Sachdeva points out that factory inspectors are now described as “facilitators” under the OSHWC Code, whose powers have been considerably diluted. As an example, he says that facilitators are no longer allowed to carry out surprise checks at factory premises and instead required to do web-based inspections.

Krishnan supports the new provisions but argues that all stakeholders should collaborate to ensure social upliftment of workers. He suggests that apart from increasing productivity at factories, “we need to revive the trade union movement in India, as collective bargaining for workers has become a lost cause”.

Krishnan is concerned about the breakdown in worker-employer relationship in the industrial areas, especially in northern India. He observes, “There is a breakdown of industrial peace or a complete surrender by workers to employer pressure. The northern belt—Manesar and Gurugram in Haryana and Ghaziabad in Uttar Pradesh—has witnessed violence, rampant strikes and lockdowns. Workers do not see value in the conciliation and dispute resolution mechanisms that, in some cases, resulted in taking the law in their hands.”

Between Krishnan’s moderate optimism and the sorry picture that emerges from shop floors in India’s smaller manufacturing establishments lies the irony of modern India. It wants to be a manufacturing hub for itself and the world while keeping the costs low. At the same time, it wants to generate respectable employment for its young workforce that is fast facing the precarity of a disappearing demographic dividend. If the government can indeed be shaken out of its slumber to implement shop floor safety and social security for India’s lowest paid workers, it could hike the compliance cost for factory owners, something they may resent vigorously, and therein lies the reality of the dark Indian factories.

*Name changed to protect identity