In May 2021, the Securities and Exchange Board of India (SEBI) proposed to revisit the definition of promoters in a company that wanted to hit the bourses. Widely seen as a move targeted at start-ups wanting to raise public money after their private-investor-led run has peaked, SEBI asked founders with over 10% stake in the company to declare themselves as promoters. Since then, many media reports have emerged stating that the market regulator informally nudged founders to adopt this practice.

The intent of the market regulator seems to be to ensure that before a company seeks public money, it should win the confidence of the prospective shareholders by putting legal obligations on founders and not just let companies treat them as mere popular faces. The earlier limit to declare a founder as promoter was 25% holding.

But the proposed lowered limit of 10% stake for founders to be considered promoters may not have any consequence in the way start-ups are governed or perceived as founders generally do not meet even the lowered criterion.

Disappearing Promoters

It is a well-known feature of the Indian start-ups that, unlike their global counterparts, founders lose or lower their stakes in the companies they establish faster than their companies win users of their services. By the time these companies become unicorns or get listed, the promoters’ stake is usually down to single digit or early double digits. Famously, Paytm founder Vijay Shekhar Sharma owned only 9.1% stake in its parent One97 Communications before it filed for the initial public offer (IPO) in 2021, while a year earlier he owned 14.7% in the company, a Bloomberg report claims. By the end of September 2022, Sharma’s stake was down to 8.91% in the company, and he was described as a public shareholder.

By Indian standards, Sharma’s is an unusual case because he still has a sizeable stake in the company even more than a year after his company got listed. His case is also peculiar because he holds an extra 4.77% stake through the family trust Axis Trustee Services. However, other start-up founders in India have not been this fortunate in retaining their stake, many of whom, like Sharma, showed zero promoter stake in the draft red herring prospectus (DRHP) and identified themselves as public shareholders with a single-digit stake.

This phenomenon is noticeable in newly listed, new-age companies like CarTrade Tech, Zomato, Paytm, Delhivery and PB Fintech. All these private-equity-driven companies showed zero promoter holding at the end of the December quarter of 2022–23, data from Ace Equities shows. The trend of the last four quarters analysed by Outlook Business shows that these companies, despite the new SEBI move and being backed by popular investors, continued to show null promoter holding, which shows that zero promoter holding in such companies is no coincidence.

Amish Tandon, lawyer and partner at Delhi-based corporate law firm Innovatus Law, feels that the status of promoters in the listed companies is more about perception than legality. He says, “While the act of the promoters completely or almost completely selling their stock in the company does not appear to have any legal ramifications, it may, in certain situations, indicate a lack of faith or trust of the creators of the company on the future of the company.”

The start-ups are founder-driven and remain associated with their names in public perception despite their dwindling stakes. The founders were gung-ho about their businesses when they sold shares through IPO in 2021. However, the subsequent earnings reported by these companies and sharp drop in their stock prices since the IPO reveal a different picture altogether.

Paytm reported a net loss of Rs 43.6 crore at the end of the December quarter of FY23, Delhivery’s loss came in at Rs 16.6 crore, PB Fintech posted a loss of Rs 23.4 lakh, while CarTrade Tech posted a profit of Rs 1.1 crore and Zomato at Rs 6.16 crore.

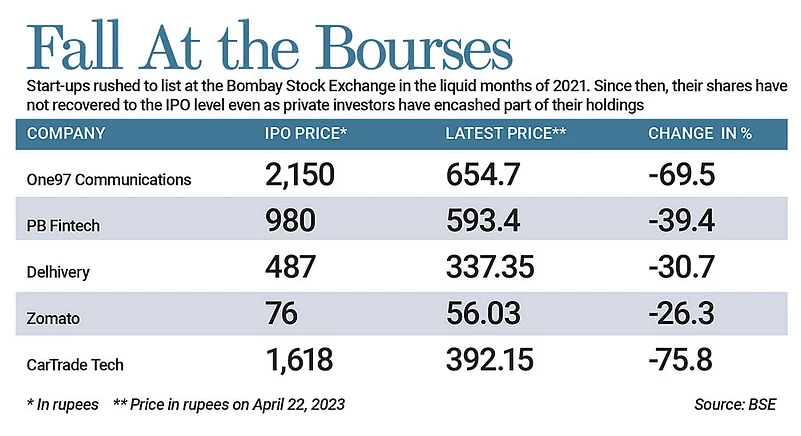

Though these companies can claim that they are either moderately in profit or have pared their losses, one of their common features is that their current share prices are significantly lower than their IPO prices. Paytm’s stock price has fallen 70% from the IPO price of Rs 2,150, Zomato’s stock has plunged 26%, CarTrade Tech has crashed 76%, PB Fintech has tumbled 39% and Delhivery has fallen 27%.

Tandon has a word of caution for founders when such a situation arises. He says, “A not very positive implication of founders not showing themselves as promoters could be people feeling that the promoters’ primary objective was, and is, short-term gratification rather than long-terms sustenance of the business. Existence of such a sentiment in the public does not augur well for a listed entity.”

Family as Promoter

Market observers contrast the promoters’ legal status in start-ups with the family-owned legacy businesses. For a country like India, where people associate family-run companies having strong promoter holding as the benchmark of investing, this trend of zero promoter holding in new-age companies is intriguing. Interestingly, the new-age companies with zero promoter holding are classified as professionally run companies.

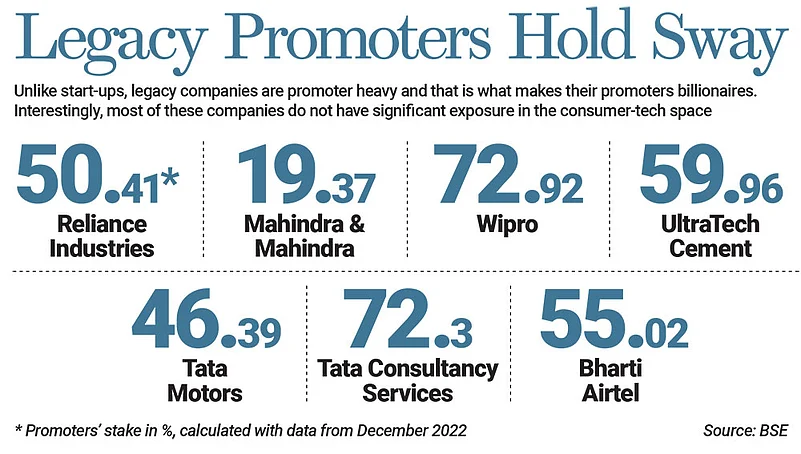

Family-promoted companies like Reliance Industries backed by Mukesh Ambani, Mahindra & Mahindra promoted by Anand Mahindra, Aditya Birla Group promoted by Kumar Mangalam Birla, Tata Group companies backed by Tata Trust and Wipro backed by Azim Premji, among others, find keen interest from common investors, as these companies have demonstrated strong earnings potential over the years and are closely associated with their promoters as they have skin in the game.

However, most of the new-age companies which got listed in the boom of 2021 when liquidity was abundant and markets were climbing new highs used IPOs to provide exit to private equity players and promoters via the offer-for-sale (OFS) route. Sharma-backed One97 Communications’ Rs 18,300 crore share sale, which was the biggest IPO of the country at the time, comprised an OFS worth Rs 10,000 crore and fresh issue of Rs 8,300 crore. Under the OFS category, Sharma sold shares worth Rs 402 crore, and investors like SoftBank, Elevation Capital and the Ant Group also divested parts of their holding in the company.

On the other hand, the case of CarTrade Techs’ Rs 2,998 crore IPO was purely an OFS by its promoters. Zomato’s Rs 9,375 crore IPO comprised of fresh issue of Rs 9,000 crore and OFS worth Rs 375 crore, Policybazaar’s Rs 5,625 crore IPO comprised of fresh issue of Rs 3,750 crore and an OFS worth Rs 1,875 crore and Delhivery’s Rs 5,235 crore IPO had fresh issue of Rs 4,000 crore and OFS worth Rs 1,235 crore.

Skin in the Game

The data from the Bombay Stock Exchange shows that the founders or promoters of these new-age companies, who were aggressively backing their respective organisations at the time of share sale, declared their holdings to the public under the new category. Sharma held 8.91% stake in One97 Communications at the time of listing—now it stands at 9.13%— and categorised himself as a public shareholder. Similarly, Delhivery co-founders Sahil Barua and Suraj Saharan held 1.79% and 1.51% stake respectively in the company at the end of the December quarter and have categorised themselves as public shareholders.

The other companies Outlook Business studied showed the same trend with respect to the founders’ position. CarTrade Tech founder Vinay Vinod Sanghi held 2.09% stake at the end of the March quarter of FY23 and describes himself as a public shareholder. PB Fintech founder Yashish Dahiya held 4.64% stake in the company as a public shareholder at the end of the March quarter and Zomato’s Deepinder Goyal held 4.32% stake in the same category at the end of the December quarter.

These trends raise the questions as to why the founders are reluctant to call themselves promoters and what happens to corporate governance issues if these companies are accused of playing with the law. Vijay Chopra, CEO of financial services firm Enoch Ventures, says that when founders have no skin in the game as promoters, they can shrug off their responsibilities in the times of crises. He asks, “Founders are not filing their stakes under the promoter category. Rather, they are doing it under the public shareholding head. If tomorrow something happens, who will be held responsible, as they are categorised as public shareholders?”

Nupur Pavan Bang, associate director at Thomas Schmidheiny Centre for Family Enterprise, Indian School of Business, however, feels that having a large promoters’ stake does not solely determine a company’s success. She says, “Promoters with high shareholdings in their firm(s) definitely have more skin in the game, as their wealth is concentrated, and the firm’s performance directly impacts their wealth. However, there are ample examples of family firms with significant family shareholding filing for bankruptcy or their decisions resulting in the erosion of shareholders’ wealth.”

Chopra argues that the trend of promoters declaring themselves as public shareholders is not good for accountability. He says, “New-age companies are backed by private equity money, and promoters of these companies make money during the IPO process. This trend is not right for common investors. SEBI should ideally question these promoters as to why they are not showing their takes under promoter category and rather showing it to be in the public category.”

In contrast, Reliance Industries, which is the country’s most profitable organisation, had 50.49% promoter holding by end of Q3 FY23. TCS, the country’s largest IT services company, had 72.3% promoter shareholding and country’s largest private lender HDFC Bank had 25.59% promoter shareholding in the same period.

“Promoters should ideally have 26% holding, as below this number they do not have the veto power in the boardroom,” says Chopra.

There are many legacy companies that also have zero promoter stake but have won the confidence of public investors. An analysis shows that at least 38 companies from Category A and Category B group of shares on stock exchanges have zero promoter shareholding, which include the likes of ITC, Larsen & Toubro, ICICI Bank, HDFC Ltd, IDFC, Karnataka Bank, South Indian Bank and Yes Bank among others.

“These are large companies and are well regulated. In the case of banking companies with zero promoter holding, there is the Reserve Bank of India watching them. ITC and Larsen & Toubro have an impressive record of decades in the Indian capital markets and have large institutions as stakeholders. Over the years, they have demonstrated adherence to strong corporate governance norms,” says Chopra, explaining how legacy companies with zero promoter stakes are different from consumer tech start-ups.

The Companies Act, 2013, requires listed companies to appoint key managerial personnel (KMP) for compliance and decision making. The KMP are certain persons/employees who are, for the purpose of the law, considered to be in-charge or responsible for the company’s operations. These positions may include the managing director, CEO, whole-time director, CFO and company secretary among others. They become liable when the company does not follow the mandatory compliances.

Generally, shareholders of a company are not responsible for the day-to-day functioning of the company—that is the responsibility of the board of directors and the KMP—unless they also hold positions which qualify them to be the KMP under the Companies Act. Consequently, in the case of any violations or non-compliance, shareholders are, per se, not considered liable and not visited with any adverse consequences.

But promoters have a different set of obligations, which are likely the reason why start-up founders do not want to classify themselves as promoters after their stakes are diluted significantly. Nitu Poddar, partner at Vinod Kothari and Company, says that the tag of promoter brings with itself a set of obligations, departure from which has far-reaching consequences. She says, “There are provisions for punishing promoters of a listed company in the eventuality of non-compliance. For instance, the non-compliance of many provisions of the listing regulations leads to freezing of promoters’ demat accounts not only for the non-compliant company but for all other securities held by them as well.”

She adds that a few clauses of the Companies Act, 2013, even impose criminal liability on promoters for making omissions, while a more problematic part is where promoters want to change their classification after listing and immediately fall under Regulation 31-A of the Securities and Exchange Board of India (Listing Obligations and Disclosure Requirements) Regulations 2015. This process is bureaucratic, as it requires permission from the stock exchange where the affected promoter’s company is listed.

When, in June 2022, healthtech Portea filed a draft red herring prospectus, it claimed, “Our company is a professionally managed company and does not have an identifiable promoter.” In April 2023, SEBI approved its IPO for Rs 1,000 crore, in which its founders Meena Ganesh and Ganesh Krishnan were classified as promoters. Observers see it as a nudge from SEBI to turn founders into promoters once again and introduce more accountability in the start-ups trying to raise public funds.