Lending is the latest trend that has caught the fancy of fintechs. Be it Paytm, MobiKwik or Cred, fintechs are looking to venture into lending to small business owners to grab a chunk of the long under-served audience seeking easy capital.

Paytm, the poster boy of India’s fintech industry which introduced digital wallets in India, forayed into lending back in 2015 while also experimenting with the online retail and payment gateway businesses. It recently disclosed that it recorded a massive 401% year-on-year (YoY) growth in its lending business in the third quarter of 2021-22. Its gross merchandise value (GMV), a key metric to assess business performance, also jumped by 123% YoY during Q3 FY22.

In the three years after Paytm entered the lending arena, the core fintech market had become saturated enough for even Paytm’s competitors to stay confined to it. Wallet killer unified payment interface (UPI) had matured as a technology in this period and opened up the payments space to old and new players, which forced more wallet providers to explore newer revenue territories. MobiKwik, another prominent digital wallet provider, got into lending in 2018 by launching a loan disbursal feature on its platform. Named Boost, it let users get loans of up to Rs 60,000 in their e-wallets. The same year, it debuted in the insurance space with its “sachet-sized products”. The company turned a unicorn last year and recently announced its FY22 results for the first nine months, which showed a revenue increase by 86% YoY from Rs 212.6 crore to Rs 396.5 crore. The company also turned profitable for the first time since its inception in the quarter ending December 2021.

Cred, which started off as a credit card repayment platform rewarding users with points for paying their credit card bills, expanded its offerings in 2018 to include rent payments and personal loans. Cred Cash, an instant credit line accessible in three steps with interest rates between 12% and 15%, was launched in 2020 in partnership with licensed banks and non-banking financial companies (NBFCs). Last year, Cred launched a peer-to-peer (P2P) lending feature called Cred Mint in partnership with LiquiLoans, a P2P NBFC registered with the Reserve Bank of India. Close on the heels of Cred was BharatPe, which also entered the P2P lending space, offering an interest rate of up to 12% for both individual lenders and borrowers.

Rivals and Soulmates

Fintechs get media attention when they undertake successful funding rounds. However, survival is another question. Nilesh Naker, partner at EY, says there is a lot of hype around fintech, but only a few will survive. “You cannot be burning cash all the time. It is understandable during initial years but it cannot be perpetual. The biggest issue is that most of these fintechs do not have the path to profitability in their prospectus,” he says.

While it is somewhat clear that fintechs cannot make profits out of a payments business alone, the question is what will really work for them in the future. If it is lending, then how far can they go in upsetting legacy players to carve a niche for themselves?

For years, legacy banks have looked at fintechs as unwelcome disruptors in the financial industry. But, this stance seems to be changing now, especially with the rapid rise in electronic payments and digital financial service models. The Covid-19 pandemic accelerated technology adoption in the financial sector. Financial advise company deVere Group has calculated that Europe saw an increase in fintech app usage by 72% after the pandemic. Mobile marketing analytics firm Appsflyer claims that India is the global leader in fintech app installs, seeing 149 crore installs from January 2019 to March 2021. This has opened up the space for tie-ups between traditional lenders and disruptors, with nearly all mid-size and large banks forging partnerships with at least two to three fintechs.

A banking sector insider, on the condition of anonymity, explains the rationale behind the collaboration: “Legacy banks have failed to reimagine the lending basket. So penetration remains low, with large swathes of the Indian population remaining unbanked. This is where fintechs are trying to enter. With their agile models, they are trying to find solutions for those who the banks do not lend to. They are trying to come out with innovative lending models.”

However, everything is not hunky-dory in the collaborative space. While fintechs bring convenience, speed and agility to the table by building on top of what banks are doing, banks evaluate and experiment with new ways of doing business but often try to throw around their weight. Fintechs tend to benefit from the strong balance sheets of the banks and the trust banks enjoy as institutions of the economy, however fintechs claim that banks do not open their application programming interfaces (APIs) for product agility. Banks, on the other hand, claim that data security and access to personally identifiable information of customers without consent are a challenge to opening up of APIs.

Uneven Path to Lending

Legacy banks tie up with fintechs in the areas of digital lending, payments, account opening, remittance solutions, gold, micro loans and cross-border inward remittances, among other areas. For banks, the biggest operational cost is branch expansion. Tie-ups with fintechs help banks in remaining branch light and penetration heavy. It can be profitable for both sides even when fintechs are smaller partners in the collaboration. “The value of a stand-alone fintech is probably a function of its own business model, but the value of a fintech that has got strong ecosystem partners increases when it is able to exponentially leverage the value the network effectively provides,” an industry expert, who did not wish to be named, says.

Industry watchers, however, warn fintechs about pitfalls of getting into a lending business where, among other issues, they may have to battle the risk of non-performing assets the way traditional lenders do. “Lending is a collections-driven business. When you lend, you have to have the ability to collect as well. Otherwise, you will run out of business. I do not think that fintechs are really geared up for it,” says Naker.

Interestingly, not everyone is in favour of such tie-ups. “Collaborating with banks erodes margins [of fintechs], making the lending business model less viable. In the long term, fintech will have to think out of the box and come up with innovative and unique solutions for consumers while maintaining their own revenue streams,” says Rajat Gandhi, founder and CEO of Faircent, a P2P lending platform now morphing into a neolending platform. He adds that not being innovative can drive fintechs out of the lending sector. It is just a matter of time, he says, “Because lending fintechs will have to own their own books”.

Aswath Damodaran, professor of finance at the Stern School of Business, New York University, agrees with Gandhi: “There is some room for intermediation here, where fintech companies can use data to better screen borrowers and then connect them to lenders, but that business is a low-margin, high-volume business where lenders will try to squeeze you out.”

Owning the books brings in regulators who minutely scrutinise lenders. Banks have a legacy relationship with the central bank and other oversight bodies, but fintechs will have to learn walking on this path afresh. Damodaran says that lending cannot be the endgame for fintechs. “Lending has never struck me a business where fintech offered much of a differential advantage. It is a grinding business, requiring monitoring and capital, neither of which fintech companies have in plentiful supply. And, it is a business where if you are an actual lender, the regulatory capital requirements will catch up with you,” he says.

In fact, Radhika Gupta, CEO, Edelweiss Asset Management, in a tweet, also raised questions about how fintech firms should be valued. “If new-age fintech businesses are finally going to earn revenues from the same traditional financial services domains—lending, AMC, etc.—shouldn’t they be valued on similar metrics as old school counterparts? Revenues and profitability, not number of users.”

It is not that fintechs are entering into a losing collaboration. “The focus of several fintechs has been customer acquisition, and because onboarding customers and products are all digital, they are able to collect and analyse a lot of digital data. That has enabled fintech to customise financial solutions at lower costs. It is been very hard for traditional lenders to serve customer segments that fintech serve,” says Shilpa Mankar Ahluwalia, partner and head-fintech, Shardul Amarchand Mangaldas & Co.

A recent report, however, has found that the dominance of fintech companies in data may not give it advantage. Moody’s Investors Service in a report said that the introduction of the UPI in 2017 has been a key to the growth of digital payments. “UPI’s open architecture means that a large user base does not necessarily make a particular service provider more competitive than others on the system,” Moody’s vice president and senior credit officer Srikanth Vadlamani said recently. As banks play an important role in facilitating UPI payments, they, too, have access to transactions that take place on the network. “Fintechs’ dominance in digital payments may not result in a significant data advantage over banks,” the report mentioned.

Innovating to Survive

A supportive regulatory environment is a must for banks and fintechs to get the best of the partnerships they forge in the future. Globally, regulators have played an important role in pushing forward the agenda of bank-fintech collaboration models, particularly because banks were hesitant to open up to the new-age business models and processes. Integration can be done easily, considering the kind of data that is analysed carefully.

But, how fintechs leverage the partnerships remains undecided. As Naker aptly says, “Going forward, the wealthtech and insurtech space will see a lot of traction. The whole enablement of the account aggregator framework along with the data protection bill, whenever it gets enacted, will set up some really innovative things in fintech.”

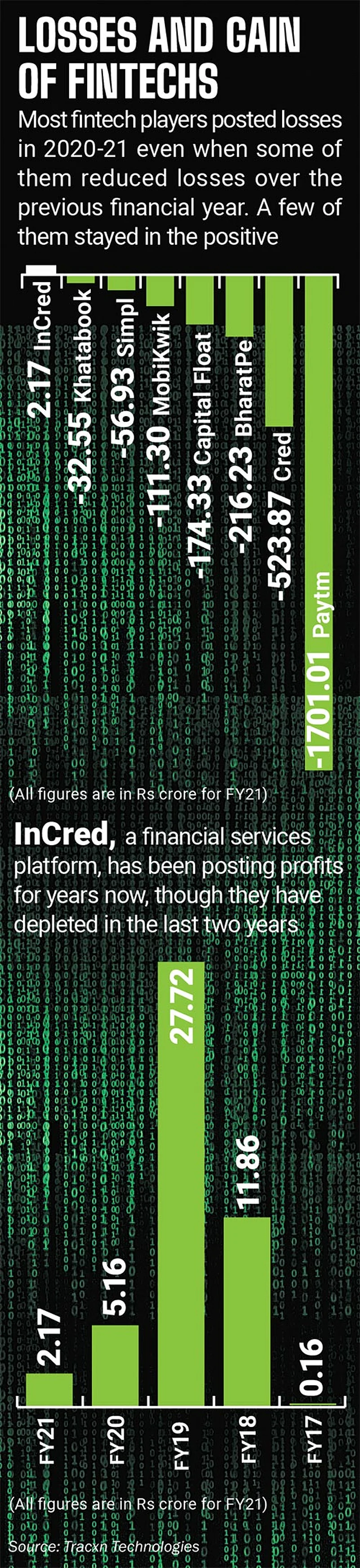

Till such a scenario emerges, the balance sheets of fintech companies, which are a mixed bag, will continue to interest their investors. Paytm, as the market leader, seems to have improved its position over the years. Its losses narrowed to Rs 1,701.01 crore in FY21 from Rs 6,197.30 crore in FY17 as its revenue increased from Rs 780.19 crore in FY17 to Rs 3,187 crore in FY21. On the other hand, BharatPe’s losses nearly doubled to Rs 1,619 crore in FY21 from Rs 912 crore in FY20 while revenue from operations jumped to Rs 119 crore in FY21 from Rs 6 crore in FY20, as per Tofler. Except InCred, whose profits in FY21 increased to Rs 217.03 crore from a profit of Rs 16.58 crore in FY17, major fintech players, like Khatabook, Cred, Simpl, MobiKwik and Capital Float have all reported losses over the years, data from start-up intelligence firm Tracxn Technologies shows.

Like other start-ups, fintech companies have consolidated their position in the market in terms of user base, but most are struggling to give their investors value for their money. Entering the lending space appears to be an attempt by fintechs to become part of a legacy viable system in a crowded market while building on their own agility to win new users. Whether this turns out to be a win-win collaboration is still not certain.