One of my most memorable — and profitable — investments in the past decade is a leading Indian pharmaceutical manufacturer of generic drugs, Cadila Healthcare. Being a contrarian value investor, scouting for good investment betsduring an euphoric 2007 was a daunting task. While most sectors, in tandem with the boom period, were scaling new heights (infrastructure being a favourite), the pharmaceutical and the IT sector seemed relatively unattractive to a majority of investors. For instance, during those days, the market capitalisation of India’s largest real estate playerwas greater than the market cap of the entire healthcare sector put together.

Against this backdrop we took a call to invest in Cadila. The stock was an underperformer in 2007 given the general disinterest in the pharma sector and more importantly the company was manufacturing a product that faced a threat of premature generic launches. The company’s joint venture manufactured the key starting material (KSM) for a patented product, Pantoprazole, which accounted for approximately 20% of the company’s profit. As a result, there were concerns surrounding the outlook for the stock. Rupee appreciation was also another factor which majorly impacted the company. Barring these two factors, the company was sound. It was the fourth largest pharmaceutical company in India, in terms of revenue, with approximately 3.5% market share.

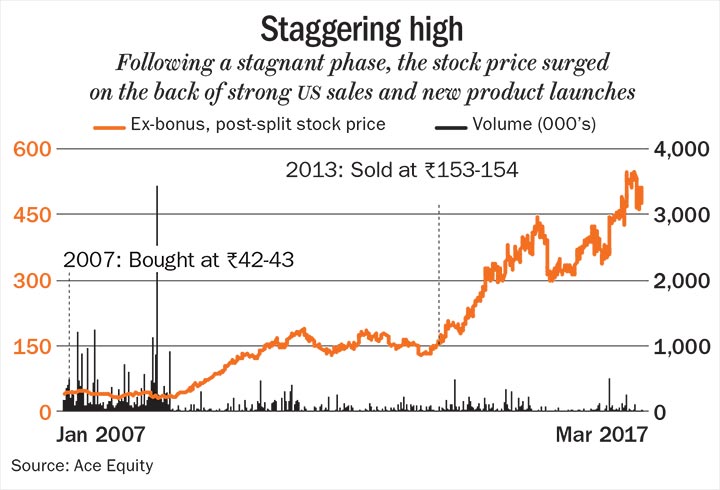

In March 2007, we bought the stock [which was trading between Rs.300 and Rs.320 (adjusted price was Rs.42-43)]. But as expected, the company’s profit growth slumped 9% in FY08 compared with 58% growth the previous year.

What gave investors confidence to stick was the management’s constant reassurance that they were working towards offsetting this problem by new product launches. However, there was no fixed time-frame for the resolution.

Over time, the firm entered into a joint venture and leveraged its capabilities to develop high-end products which have steeper margins and, thereby, expand its active pharmaceutical ingredients (API) pipeline. This, along with strategic acquisitions in the European market, enabled Cadila to restore the buoyancy in its profit. The company also made a series of acquisitions, thus ramping up its presence in countries such as Brazil, Latin America, Spain and South Africa.

Results were encouraging at every step: in FY09, the company reported a 16% rise in profit. Meanwhile, even the US business had started improving, helping offset the losses owing to Pantoprazole. As such, the earnings witnessed a drastic improvement with consolidated PAT and EPS nearly doubling in FY10.

The stock price remained flattish for the most part till July 2009, more than two years of our holding the stock. Since October 2009, the stock price started increasing steeply. We finally sold the stock completely in December 2013 [while the price was hovering around Rs.780 (adjusted price was ~Rs.150)]. During the holding period, the share price recorded a surge of a staggering 290%.

When we bought the stake in the firm, it constituted 3-4% of one of our funds and then later with the surge in share prices it constituted nearly 8% of our funds. A clean balance sheet, a management that was focused on the business rather than getting carried away by the mood of the moment by diversifying into unrelated businesses, and a strong promoter holding, which remained unchanged at about 70%, emboldened my belief in the capacity of the management to turn this tide of adversity.

Investing lesson

In retrospect, one of the key realisations I have had is that, the price of certainty is that there is no bargain, and the price of uncertainty is there is a bargain.

When we bought the stock, there was no clarity how and when the company could gain back business momentum. If the company had put forth a definite timeline for the resolution of the problem, it would have attracted interest from other investors as well.

The recipe for a great bet, according to me, is a combination of sound fundamentals, an enterprising management, high entry barriers (for investors) owing to uncertainty and, therefore, requiring immense trust in your decision and, ultimately, a long-term investment horizon which warrants a patient mindset.

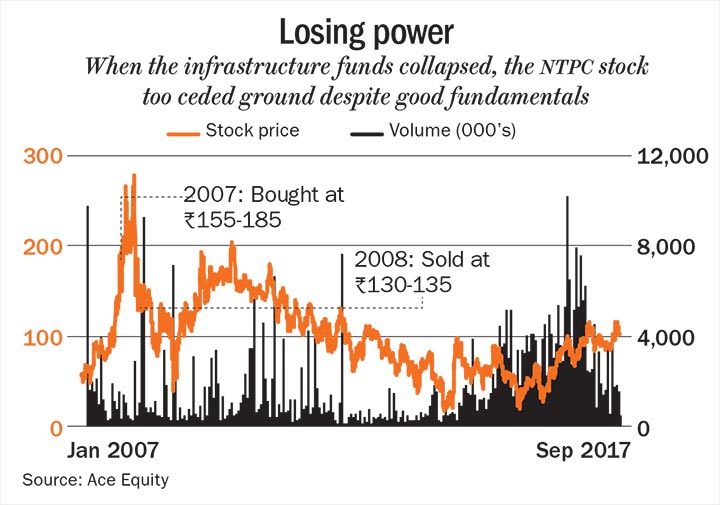

In his famous book, Thinking Fast and Slow, Daniel Kahneman elucidates one of the heuristics — anchoring and adjustment — which impacts the way we assess probability at an intuitive level. A person pins down a starting point (anchor) based on the available information and then lets this starting point (which may not necessarily be an accurate one) influence (mostly unfavourably) future decisions about the object in question. And it is this starting point which lies at the core of my experience in investing in National Thermal Power Corporation (NTPC), a decision which did not turn out quite well, even though it was a good bet on a fundamental basis. This stock was a part of couple of our funds between May 2007 and December 2008. In May, we started buying the stock [when it was priced between Rs.155 and Rs.185].

In the heady days of 2007, there were huge inflows into infra theme funds. But we liked power utilities. Utilities, according to Warren Buffett, is a sector which promises only moderate returns, but it also presents you with an opportunity to invest huge sums of money and that was a key motivation to invest in NTPC. In Capital Returns, financial historian Edward Chancellor elaborates that when exploring investment opportunities, most individuals focus on sectors which are expecting a huge surge in demand, while a good starting point is to look at sectors where supply will be limited in face of rising demand. The high entry barriers associated with the power sector, in that sense made it an attractive opportunity.

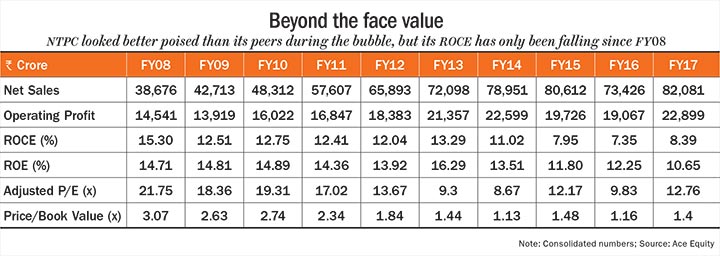

NTPC was prudent with its capital allocation unlike its peers and kept away from major Ultra Mega Power Project (UMPP). In those days, UMPP was the flavour of the season and private players were bidding aggressively even though it was evident that those projects would have hardly given higher returns.

Also, this company had a payment cycle backed by the RBI, in case the states were unable to fulfill their payment obligations. So, amid companies that were grossly misallocating capital, this name stood out as a relatively good bet. In a bull market, the metric we like to use is the trailing P/E and P/B that tell you what is the embedded growth in the stock. On those metrics too, the stock was better placed than its peers.

But the irrational exuberance surrounding infrastructure stocks resulted in a surge in prices, turning a blind eye to the company fundamentals. However, after the crash, the stocks without earnings, without balance sheet and with capital allocation problems fell sharply. In those days, there was a general perception that the complexion of returns would change in the times ahead. However, that was not the case as NTPC was a regulated entity.

NTPC fell less than its peers but lost value, nevertheless. During my holding period, the stock price reduced by a steep 27.7%. To make matters worse, with the onset of the 2008 crisis, there was a huge outflow of capital from infrastructure funds, which further constrained our ability to hold on to the stock. We finally exited in December 2008 [with the price lingering around Rs.130].

Investing lesson

One of my key takeaways from the whole exercise is that boom and bust cycles take much longer to play out than the time estimated by investors and during the bubble phase it is difficult to get a fair idea about the valuation of the company. Once you notice that a sector has entered a bubble phase, it’s best to switch from that space for the next 4-5 years. When there is bubble, attaining steady state takes time, and that price may be much lower than anticipated. We as investors are too tied to our anchors and assess everything in light of that anchor and, hence, are not able to successfully predict the likely bottom of a stock. Investing is part science, part art; so walking on that tight rope, although exhilarating, is a challenging task.

A key realisation post this experience has been that a company may be making good decisions about capital allocation, it may have good performance ratios and could be decently valued, and yet, the stock may fail to deliver. This experience also reiterated for me the old adage of financial world that hindsight is 20:20 — it’s easy to know the right thing to have done after something has happened, but it’s hard to predict the future.