Trichy’s is a love story gone wrong. Not the wrong where the lover next door turns out to be a stalker and murderer. Goodness, what do people watch on Netflix these days! This is the more forgivable kind of wrong. Fidelity-in-the-age-of-Tinder kind of wrong. Only one side took their vows seriously.

Fabricators here stayed painfully loyal to one of the biggest public sector units of the country, Bharat Heavy Electricals Limited (BHEL) while the Maharatna moved on. They served the PSU almost exclusively, while BHEL upgraded its products and couldn’t carry its partners along. To be fair, the fabricators’ fealty was from force of habit than unbridled passion for BHEL’s transformers and high-pressure valves, and that is always a bad call in love and business.

Back in the day…

Back in the day…

Tiruchirapalli is known for fabrication, an identity it got from its association with BHEL. In the early seventies, the PSU looked to set up shop in south India. Trichy, being geographically well-connected and endowed with vast expanses of land, became BHEL’s location of choice. The heavy electricals maker began subcontracting the manufacturing of coal power plant components when it had excess orders. As business grew, these ancillary entities developed into full-fledged industrial fabricators. What also grew was their dependence on BHEL.

Between 2008 and 2012, besides BHEL, major companies such as L&T and JSW were also pursuing power projects. However, being a government entity, BHEL enjoyed an advantage over private competitors. When bidding for a power plant tender, the government awarded the contract to BHEL even if the PSU’s bid was higher, even up to 15%, than the lowest offer. Given BHEL’s upper hand, Trichy’s ancillaries ramped up capacities to meet the upcoming demand. Some of the ancillaries considered this their best time in the business.

Understandably, BHEL fell into a comfort zone because it was the government’s child, and the parent would do everything to pamper the PSU. The Government did, to a point, until it no longer could. At the turn of the last decade, the government began floating international tenders for its power plants. It was then that the World Bank, which was part-funding the projects, mandated that all bidders be considered equal. And thus, BHEL lost its preferential advantage. “This marked the first day of the fall of BHEL, Trichy,” says S Sampath, CEO, Velmurgan Industries, and ex-CII vice president, Trichy district.

Now, the government instructed the PSU to be more competitive in pricing. What was earlier a seller’s market (wherein BHEL called the shots), now became a buyer’s market. The tender went to the lowest bidder. As a result, BHEL had to reduce its prices and it needed smart partners to function more efficiently. In Trichy, meanwhile, the ancillaries had become lax, not adding value to the components that they produced. They took the steel provided by BHEL, cut and welded it as per the drawings that came from BHEL, and sent back the finished part.

Somewhere along the line, BHEL fell behind in India’s drive to reduce emissions. It kept churning the 500MW power boilers instead of upgrading to the more efficient 650MW and 880MW units. Some ancillaries even admit that perhaps they didn’t hop on to the renewable energy bandwagon as earnestly as they should have. But as Sampath says, “In business, it’s when you’re most comfortable that you must scout for opportunities.” The big blow came in 2014, when the government stopped issuing licences for new coal-based power plants. BHEL’s clients that placed orders for coal-based power plants backed out.

Now there were 600 fabricators vying for a handful of power plant makers. What happens when there’s too much supply with few buyers? Precisely. The price plummets. “The reduction in orders brought in cut-throat competition among the local fabricators,” says AR Syed Arif, Chairman, CII, Trichy. Margins fell to wafer-thin, if not negative.

MSMEs in Trichy can never win a price war, because they start from a geographical disadvantage. Most of India’s steel plants (Tata Steel, SAIL) are located in the eastern part of the country in states such as Odisha, Jharkhand, West Bengal. JSW and Essar are in the west (Maharashtra). Given the distance, the units in Trichy pay nearly Rs.10,000 per tonne for freight. In contrast, a unit in Nagpur or Vijayawada pays Rs.2,000 to Rs.2,500. But plants in Trichy ventured forth in this disastrous direction till losses exploded in their face. This is the prime cause for close-down of businesses in the cluster. Then came the Goods and Service Tax (GST).

Across the spectrum

Depending on who you ask, GST has either been a boon or an absolute bane. Take K Premanathan, MD of Anand Engineering, for instance. Everyone from the owner of the next door factory to the stray autorickshaw that runs around Trichy’s Thuvakudi area (one of the city’s factory hubs) has a high opinion of Anand. In fact, it’s one of the few factories that have thrived during this current downturn.

A little over four decades ago, Anand too started as an ancillary to BHEL. Unlike the others, Premanathan diversified into wind energy and took up contracts with NEPC Micon in 1992. “In 2006, there was a slump in wind business. We switched to building bodies for Caterpillar dumpers,” he says. Besides Caterpillar, Anand builds components for Komatsu excavators and windmill towers for Siemens Gamesa. It’s this flexibility that has allowed Anand to flourish while clocking Rs.2.5 billion in FY20 revenue, and not laying off anyone from its 600-strong workforce.

It’s a similar story for Velmurugan’s Sampath who prides himself and his team of 450 for constantly looking for newer avenues. “I don’t depend on more than two clients from the same sector. If first two are from wind, third will be from steel, and fourth will be from mineral,” he says. The company clocked Rs.1 billion in the last fiscal and hopes to add another 8% by March 2020. Both Premanathan and Sampath consider GST to have made business simpler than ever before.

Sampath says, “A technocrat-industrialist needs not just technical ability, but also financial discipline.” He explains what should be common sense, that diversion of long-term capital for short-term goals is also detrimental. “If you make profit, don’t go and spend it on a fancy car. You need to invest that money back into the business if you want the venture to grow,” concludes Sampath. This is also where most of Trichy’s businessmen faltered.

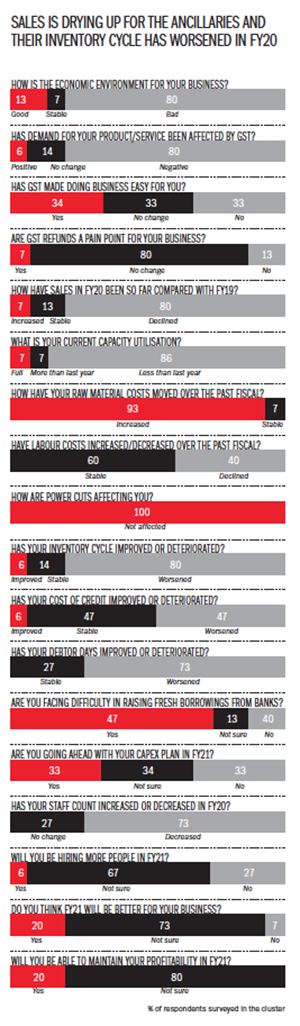

“From 2016 onwards, 36 units have been shut down, 60 units have become NPAs, and another 250 units have been declared stressed assets,” says Rajappa Rajkumar, whose rundown facility neighbours Velmurugan’s thriving one. He says the crisis stems from lack of working capital, than poor allocation. Sales is drying up even while banks have to be paid. In the midst of this cash crunch, it is difficult for entrepreneurs to diversify, like S Punniyamoorthy tells us.

Punniyamoorthy is a revered man in the Tiruchirapalli District Tiny and Small Scale Industries Association (TIDITSSIA) circle. He is the managing partner of Cauvery Engineering Works, an ancillary unit to BHEL. He and R Ilango, President, TIDITSSIA — who also runs an ancillary unit for BHEL — face similar issues. They would have liked to have clients in various sectors like Premanathan and Sampath have. But, working for smaller contractors means delayed payment cycles. With BHEL, you are guaranteed payment on time. “Although payment disbursal is supposed to take place within 45 days, clients pay late,” says Punniyamoorthy. Without taking the name of the client, he mentions how the order was delivered on August 2, 2019, while he received the payment on December 27, 2019. “On top of that, we need to shell out 18% GST on the order value, and that locks away valuable working capital,” he adds.

One solution would be to enforce large corporations to disburse payments to SMEs upon receiving their input tax credits. TIDITTSIA has already approached the Finance Ministry for this. Even if measures are swift, Punniyamoorthy suspects that recovery will take about two years. “Of Trichy’s 600 units, about 250 have been declared stressed assets. Most are running at 20% capacity. I’m barely working at 25-30% capacity,” he says.

Panic in the city

It is easy to shut shop and go home but people like Rajkumar, Velmurugan’s neighbour, who is the president of BHELSIA, have been working on a resolution. First stop, banks. “A proposal has been made to banks to turn claimed portion/present outstanding into a term loan. The term loan will be repayable in seven years so the unit can draw fresh working capital. This is only possible for the 250 stressed assets, but the market will take about one year to bounce back,” says Rajkumar. Hence, over and above the seven years of repayment, the units in Trichy have asked the finance ministry for a one-year holiday period where the units only pay the interest on the installments. The trouble remains that the banks haven’t implemented this proposal.

“The other way out is to rope in the government with 25% equity investment. This way, the banks risk providing a relatively lower 75% of the working capital while the government chips in the remaining,” explains Rajkumar. The units in Trichy intend to repay the government after paying back the seven-year term loan to the banks. The banks could auction all the NPAs and stressed assets. But according to him, the auctioned equipment will fetch a paltry 20-25% of their value when sold as scrap. “A lot of expertise has been developed at the units declared NPAs and about 6,000 workers are employed at these factories. The expertise will be lost, and there will be mass unemployment,” Rajkumar argues.

He is hopeful of BHEL picking up railway and military orders, which will help Trichy’s fabricators fire up again. Full-fledged implementation of these contracts is likely to take five years, estimates Rajkumar. To stay prepared for these contracts, BHELSIA has proposed to the government a Rs.220 million project to build a common facility that houses high-end manufacturing and fabrication equipment. Rajkumar is optimistic of even receiving Rs.180-190 million from the government for the project. “If the clearance come through, the facility can be expected to be up and running by, 2QCY20,” he says.

While intervention from banks and the government would be welcome, NP Sukumar believes fabricators and contractors have to come to an understanding first. The managing director of Tiruchirapalli Engineering and Technology Cluster says, “First, a contractor, be it a PSU or a private player, mustn’t squeeze a fabricator beyond their pricing capabilities. Second, payments must be done on time, within 45 days.” Usually, after the fabrication work is done, client companies don’t take their deliveries on time. So, the fabricators carry inventory for long periods and have their working capital stuck in one project. If this supply chain is fixed, he says, MSMEs won’t even require banks to extend special credit to them.

Whatever the differences, every single one of Trichy’s entrepreneurs and fabricators will agree that the city has hung on to its favourite PSU for far too long. Under the Paris Agreement (PA), India aims to reduce emissions intensity of the economy by 33%–35% by 2030. Climate Action Tracker (CAT) is an independent body that analyses governments of 32 countries. It states that in order to attain the 1.5 Celsius limit in temperature rise, there needs to be a phase-out of coal in the power sector by 2040, globally. “Power boilers are a sunset industry from CII’s perspective. But we’re still holding on to it,” says Arif.