Cities like Chennai and Delhi are outsourcing waste management with tech-heavy, performance-linked contracts.

Sanitation workers across the country face wage cuts and lack of safety.

Indore, Pune and Ambikapur among others provide a replicable model of efficiency gain while aligning with worker dignity.

Privatisation works only if contracts ensure fair wages, accountability and inclusion.

The morning breaks in Chennai’s Royapuram, sunlight mingled with the sour breath of the sea and the city: fish scales, peel, damp salt. A heavy breeze pushes the smell through the alleys where hawkers spread their wares and children wait in uniforms for school buses. Workers in faded clothes, some with cracked boots and bare hands, go door to door, heaving sacks of the previous night’s refuse. This is how Indian cities start each day: on the backs of people most of us choose not to see.

On 1 August in Chennai, the ritual broke. Conservancy in Royapuram and Thiru Vi Ka Nagar had been handed to a private operator. Within hours, thousands of sanitation workers thronged the Ripon Building, fearing brutal pay cuts. The strike lasted nearly two weeks, often in the face of heavy-handed police action. Unmoved, the civic body pressed ahead, touting “smart” collection: AI dashboards, RFID bins, biometric rolls and a fleet of battery vehicles.

Chennai is now a test case: can privatisation clean up waste without squeezing its unseen warriors? Sucheta De, AICCTU national vice president, says, “The private agency can anytime run away from its responsibility of providing job security to workers. Outsourcing of sanitation work shows that the government is escaping its duty of being a primary employer.”

Delhi offers a parallel, and equally pungent, reminder. In Jangpura, a dump heap heaves before dawn, leaking a sulphurous tang across the colony, smoke curling up from slow fires deep within the mound. Passersby wrinkle their noses, some mutter about dengue or clogged drains, and life goes on. For all its capital pretensions and billion-rupee budgets, the city has for decades failed to flatten its embarrassing landfills. Mountains of waste at Ghazipur, Bhalswa and Okhla stand as monuments of neglect, while mining and composting rarely keep pace.

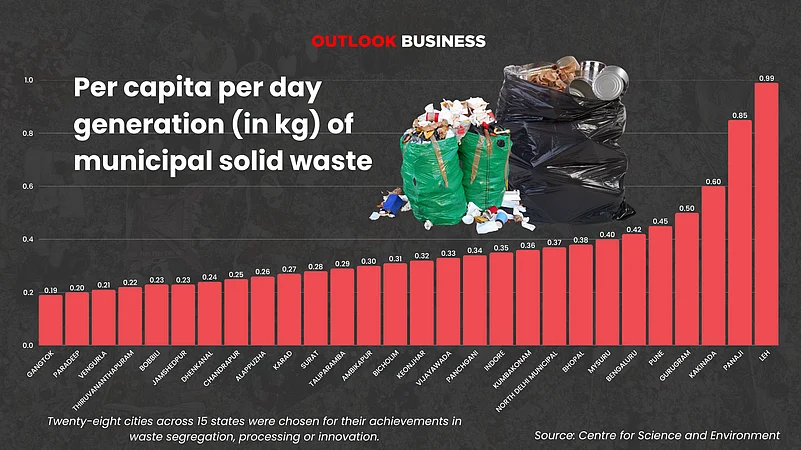

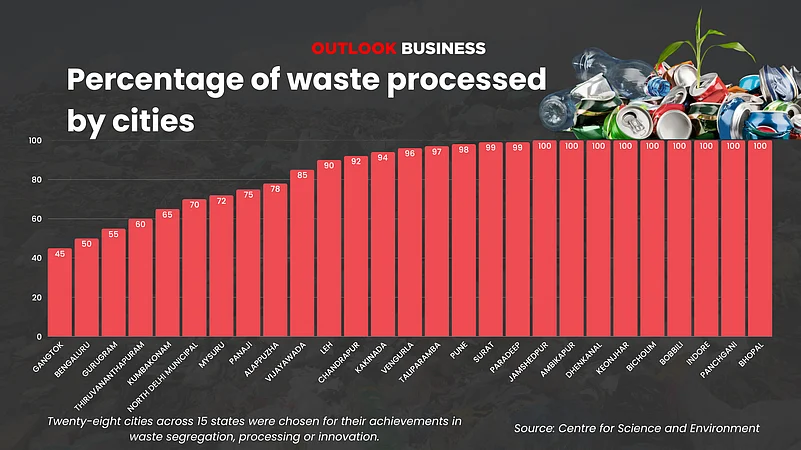

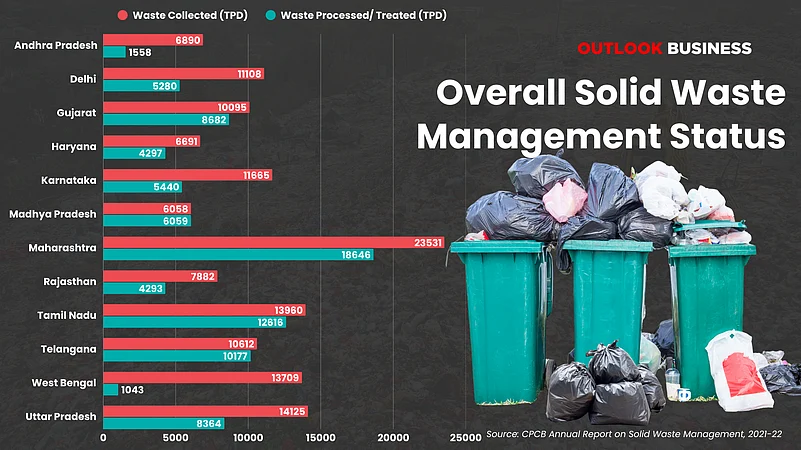

The Central Pollution Control Board’s annual report for 2020–21 estimated that urban India generated roughly 160,000 tonnes of municipal solid waste every day. The following year, the figure crept closer to 170,000. About 95% was collected. Only about half was treated by any “scientific” method such as composting, biomethanation, recycling or waste-to-energy. A little over 18% goes to landfills, and 32% of it is unaccounted for. MoHUA, in a 2024 parliamentary brief, cited progress toward “about 80% scientifically processed” waste, but independent studies suggest the rate is underestimated and collection overestimated, since rural areas, open burning and informal recycling are excluded.

Behind tonnes of plastic and peel are people. Dalberg, in a study echoed by WaterAid and a World Bank consortium, estimates that around five million Indians earn their living in sanitation, sweeping streets, collecting refuse, emptying sewers, handling faecal sludge. Millions more survive as waste pickers, keeping recyclables in circulation with no fixed pay scale, no protective equipment, no insurance and often no recognition.

The Chennai Case

Chennai’s decision to outsource two of its largest zones did not arrive in a vacuum. As early as 2020, Urbaser Sumeet was contracted to manage seven southern and western zones under an eight-year agreement, while Ramky Enviro took four northern zones. By July 2025, 10 of the city’s 15 zones were already under private operators, with Royapuram and Thiru Vi Ka Nagar slated for transfer. The new package is reportedly worth nearly ₹2,400 crore over a decade, with explicit promises of mechanisation, smart monitoring and better coastal cleaning.

Councillors stormed out of a Corporation meeting over job security, even as the body approved oversight engineers and compliance monitors. It was a tacit admission that outsourcing without referees dissolves into subsidy without accountability.

For workers, the risk was immediate. Rumours of wage cuts, patchy benefits and contractor discretion rippled through the workforce. The High Court’s insistence on wage protection underscores that transitions in this sector cannot be left to goodwill.

The Workers’ Reality

Spend a morning on any compactor route, and the data sheets dissolve. Work begins before dawn, often without gloves or masks. Drains are cleared by hand, sharp glass picked from mixed piles, and medical waste lifted in plastic sacks. Permanent municipal employees earn salaries with a provident fund, leave and health cover. Contract workers, often doing the same jobs, lack ID cards, insurance, predictable shifts or protection from arbitrary dismissal. Moses Andrew of Plastics For Change says, “A large proportion of frontline waste work is carried out by contractual, daily-wage or informal workers who often lack the rights, protections and benefits available to permanent staff.”

In Chennai, workers employed under the National Urban Livelihoods Mission (NULM) have long demanded permanent jobs. Instead, they face the threat of lay-offs as services are handed over to private firms. De of AICCTU says, “In most cases, they do not even get minimum wages.”

It is not only the frontline worker who is invisible. The informal pickers who salvage plastics, cardboard, glass and metals keep the recycling economy alive. “The urgent priority is to ensure that all waste collectors, whether permanent, contractual or informal, enjoy the same rights to fair pay, safe working conditions, social protection and dignity of labour,” says Andrew. In Pune, their inclusion through SWaCH, a pioneering worker-owned waste-picker cooperative formed in partnership with the Pune Municipal Corporation, has given more than 3,800 members a modest but stable income. Brajesh K Dubey, circular economy professor at IIT Kharagpur, says, “It is one of the best examples in India.” Yet its pro-poor PPP model remains under constant threat from contractors.

Efficiency Versus Exploitation

The case for private operators is straightforward on paper. Municipalities face swelling cities, limited fleets, stretched budgets and statutory targets on segregation and disposal. Infrastructural gaps such as door-to-door collection, material recovery centres and scientific landfills reduce efficiency.

A recent ScienceDirect study of solid waste management in 10 smart cities suggested that heterogeneous waste was disposed of unscientifically in open dumps, often functioning beyond capacity, with only a handful of examples of capped sanitary landfill sites. Municipal frameworks lack the resources and technical expertise to manage heterogeneous waste, evident in 80% of urban India.

Across the country, more than 120 public–private partnerships (PPPs) outsource collection, segregation and processing services, according to the Department of Economic Affairs. Private contractors promise capital investment, mechanised vehicles, route optimisation and dashboards that pinpoint gaps. When monitored with time-stamped data, leakages can be reduced. Chennai’s latest contracts promise exactly this, with payments tied to device-level reporting. Dubey says, “If private companies bring in new technology, such as better source segregation methods, GPS tracking or mechanised sweeping, it can improve waste management. Professional management also helps, which is often lacking in municipalities.”

Delivery is more complicated. Tipping-fee models, which pay by the tonne delivered to transfer stations, can perversely reward more mixed waste rather than better segregation. Contracts that prize “coverage” without insisting on outcomes leave landfills swelling behind cosmetic cleanliness.

Irregular payments, weak fee systems and land delays stall projects. Stringent bid rules also exclude smaller enterprises, as Bengaluru’s failed street-sweeping tender showed.

Despite privatisation in 10 of 15 zones, Chennai managed to rank only 38th nationally in Swachh Survekshan 2024–25. At the state level, it slipped from fifth to 104th in a year.

Worst of all, efficiency is often extracted from the labour margin. Workers in Chennai feared cuts of ₹8,000 on already tight pay packets.

A balanced answer to the question “Should waste management be privatised?” is therefore conditional. It can work if — and only if — contracts lock in strong municipal oversight, transparent payment formulas, enforceable penalties for non-performance, protection for workers and clear KPIs on segregation and diversion. Without those, privatisation slides easily into exploitation.

Yet not all outcomes are bleak; a handful of cities have shown what disciplined design and oversight can achieve.

Indore, a Replicable Model

As highlighted by India Development Review, Indore’s waste is transformed into raw material for footpaths, road pavements and bricks. Bricks, produced in a privately operated facility, are procured for government projects such as NREGA works. “We ensure we earn revenue from every waste generated and create useful products from them,” says Indore Municipal Corporation Commissioner Shivam Verma. “Our vendors earn by selling EPR [extended producer responsibility] credits, which we get in the form of royalty,” he adds.

Collection vehicles are monitored, and if delayed, strict action is taken. “Since the initial stage is so robust, it facilitates processes later in the waste management chain,” he added. Vehicles have the facility for segregation in six categories before reaching transfer stations.

Indore has been ranked India’s cleanest large city for seven years in a row. Its success rests on disciplined systems: near-universal door-to-door collection, strict route planning, segregation at source, decentralised material recovery facilities, user-fee models and constant municipal oversight. By one estimate, Indore diverts all its waste from dumps, turning wet waste into compost and bio-CNG and recycling dry fractions. “Biogas generated by wet waste processing is used by collection vehicles and city buses. RFD or refuse-derived fuel [made from non-recyclable dry waste such as plastics, paper and textiles) is sent to cement factories,” Verma says.

But beyond systems and technology, Indore’s achievement reflects a cultural shift: a near-total enrolment of its citizens in the mission. In the city, cleanliness is a shared civic ethic, with residents actively segregating waste, paying user fees, and holding the municipal corporation accountable. It is this blend of structure and social buy-in that makes the city’s makeover irreversible.

Ambikapur, in Chhattisgarh, offers another story. There, 470 women employed through the NULM run collection, segregation and processing, earning revenue and minimising landfill disposal. In 2022, it was recognised as India’s most self-sustaining small city.

Pune, as noted, shows the power of integrating waste pickers into the system. Their work saves crores for the city and avoids hundreds of tonnes of landfill daily. Similarly, in Bengaluru, women garbage collectors from Hasiru Dala cooperative redirect 1,050 tonnes of waste daily, saving ₹84 crore yearly.

Across cities, citizen-reporting apps, GPS-tracked fleets and RFID attendance have raised collection to near-universal levels and pushed segregation toward 90–95%.

However, Andrews says, “Comprehensive examples that demonstrate both high cleanliness standards and consistently good working conditions together are absent. Cities like Indore have introduced measures such as regularised wage payments, welfare schemes and periodic health check-ups, but challenges persist.”

Global lessons are equally telling. Seoul, from the 1990s onwards, built a pay-as-you-throw regime with unit-priced bags and smart kiosks weighing food waste. Within a decade, it drove double-digit reductions in waste and created a culture of careful separation. Latin America, too, shows how recycler cooperatives, once informal, won recognition as public service providers — proof that efficiency and dignity can be paired when rules demand it.

Delhi’s Hard Choices

Delhi carries a notorious reputation — a city that wears its sanitation failures like a crown. In 2021, the Municipal Corporation of Delhi (MCD) undertook a fundamentally redesigned waste-management contract. The approach shifted toward a performance-based service-delivery model that demanded more integrity: vendors had to deliver outcomes, insist on segregation at source, push waste into decentralised processing before landfills and submit granular daily reporting right down to street beats. The tender even specified provisions for user charges, grievance redressal, protective gear and insurance for workers. Manoj Verma, superintendent engineer, MCD, says, “Penalty system in the new performance-based tenders has been strengthened. We have provided the contractors with machines, and the number of primary vehicles has been increased. If dhalaos (waste collection points) are not cleaned, a 3–5% penalty is charged. Some tenders mandate third-party tenders.”

If the Swachh Survekshan’s data is any indication, the tide has started to turn for Delhi. In 2023, MCD ranked 90th among urban local bodies, scoring 6,115 out of 9,500. By 2024–25, it had climbed 59 places to 31st in the million-plus cities category. This leap suggests that the revamped contract design may finally be yielding results.

And yet, the numbers reveal unfinished business. MCD scored nearly full marks on door-to-door collection, but segregation has stalled at around 58% and actual waste processing remains stuck at 51%. Waterbody cleanliness, public toilets and grievance redressal continue to lag. MCD's Verma attributes this to “poor enforcement of user fee norms” and behavioural issues. “User charge was notified long back in 2017, but when we tried implementing, political lobbies didn’t let it happen,” he says.

Underlying these gaps are chronic shortages of funds, manpower, and land. “We have written to DDA to provide land for building dhalaos,” says Verma of MCD. “The city’s masterplan kit calls for at least half an acre of land for decentralised composting in every ward. But we don’t have land, which is leading to low segregation,” he adds.

Officials say the picture will improve as processing capacities expand. Of the 11,500 metric tonnes of waste collected daily, only about 7,200 are processed. “By 2028, four plants with a total capacity of 2,000 metric tonnes will be added,” says MCD's Verma.

Meanwhile, the New Delhi Municipal Council (NDMC), which governs only the city’s Lutyens’ precinct—just 2% of the total area—raced up the sanitation index from 7th in 2023 to the very top in 2024–25, bagging the coveted Super Swachh League City Award. The reason: a concerted push for reduce–reuse–recycle centres, zero-waste colonies, composting hubs and a five-star Water+ certification. “NDMC has adopted the Anupam Colony model where the colonies do on-site composting of wet waste and channelise all the dry waste after removal of reusable and recyclable items. Horticulture waste is also processed into compost in compost pits,” says Keshav Chandra, NDMC chairperson.

Chandra says, “Effective sanitation is possible only when several departments converge, including sanitation, civil engineering, horticulture and enforcement, and there is regular engagement with the workers.”

In the NDMC area, only waste collection runs on a public–private partnership model; all other operations are managed directly by the urban body. “What matters is the management of the corporation. If it is well managed internally, there is no need for outsourcing. Having said that, it is hard to replicate the model in any other city as every city has its unique challenges,” says Chandra.

A Way Forward

Chennai feels like a hinge moment because every trade-off is visible at once. The city’s density, beaches and scattered legacy contracts make modernisation attractive. Workers’ fears of slipping wages and protections are equally legitimate. The compromise struck by the High Court is a reminder that the poorest cannot subsidise the rest of us.

There is a credible middle path. Outsourcing can work if contracts mandate wage floors indexed to inflation, enforceable by third-party audits. Payments must be tied to outcomes that matter: segregation at source, diversion from landfill, verified compost quality, transparent emissions monitoring, and accident-free workdays. A share of routes or sorting lines should be reserved for cooperatives. Cities must practice full-cost accounting, showing who saves, and how.

Systems that ignore sanitation workers and the informal waste sector cannot be sustainable. Andrews says, “It is possible to ensure effective privatisation only if there is strict enforcement of labour laws, regular monitoring by the civic body, transparent grievance redressal systems and involvement of unions or worker representatives. Without such oversight, efficiency and cost-cutting could come at the expense of workers’ well-being.”

At its heart, waste management is not about whether a control room can track a truck at 6.30 a.m. It is about whether the people on that truck can go home safe, with wages they can trust, and the assurance that their city sees them. That is what progress will look like when the bin is closed and the street is quiet again.