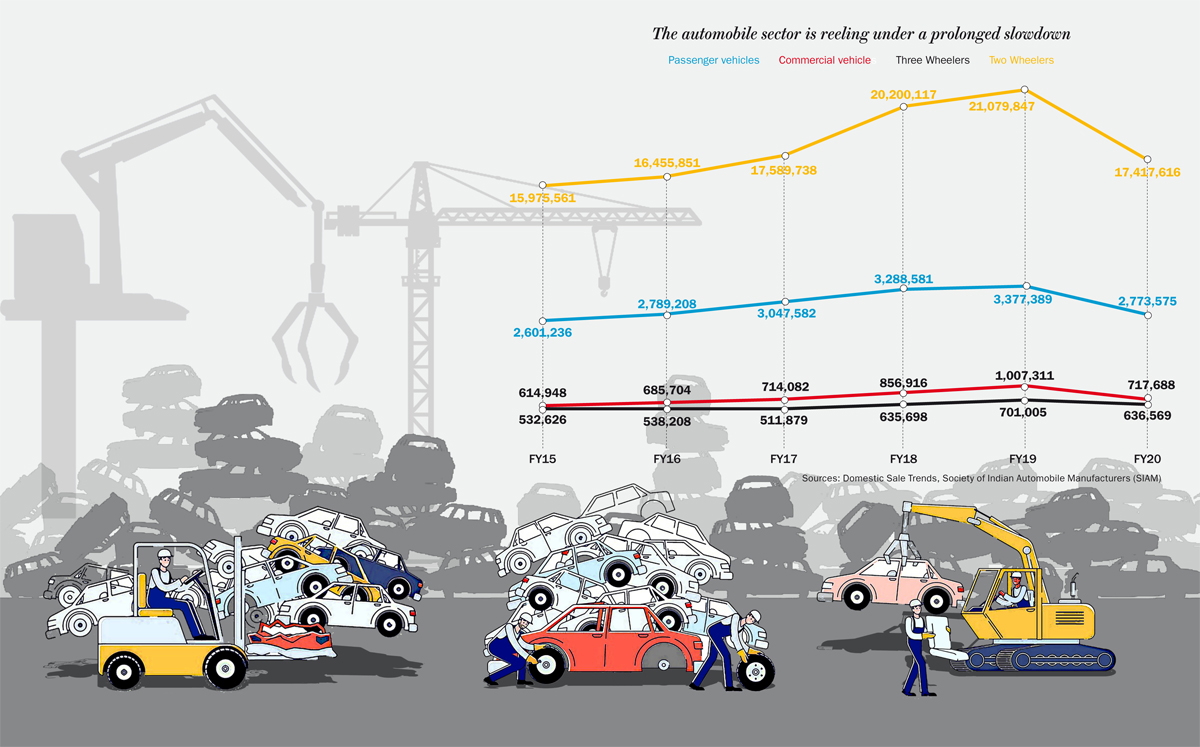

India’s Vehicle Scrappage Policy, explains in a nutshell, everything that is wrong with our policy making process. It was way back in 2013 that the Society of Indian Automobile Manufacturers (SIAM) first made a case for it to a Parliamentary Standing Committee. Seven years later, the auto industry is still waiting for it to boost demand that was initially affected by the slowdown and then the pandemic – SIAM’s latest figures suggest that during FY20, domestic sales slumped to 21.54 million, down 18% year-on-year.

While the policy is set to roll out in the next few days, newspapers have rushed to highlight a ‘ Rs.430 billion business opportunity ’, by boosting sales for the auto industry. But, there’s more to this story. Transportation takes a huge toll on the environment. According to the International Council on Clean Transportation (ICCT), vehicles account for a third of particulate-matter (PM) pollution in India. The older they are, the worse the damage they cause. For example, CVs manufactured before 2000, which form just 1% of the total fleet, account for 23% of total PM emissions. Therefore, end-of-life management of vehicles is crucial, particularly since Central Pollution Control Board estimates the number of ‘clunker’ vehicles to grow from 8.7 million in 2015 to 21.8 million in 2025 — that’s 2.5x.

Transportation takes a huge toll on the environment. According to the International Council on Clean Transportation (ICCT), vehicles account for a third of particulate-matter (PM) pollution in India. The older they are, the worse the damage they cause. For example, CVs manufactured before 2000, which form just 1% of the total fleet, account for 23% of total PM emissions. Therefore, end-of-life management of vehicles is crucial, particularly since Central Pollution Control Board estimates the number of ‘clunker’ vehicles to grow from 8.7 million in 2015 to 21.8 million in 2025 — that’s 2.5x.

As of now, scrappage in India is managed largely by informal units, which are highly inefficient. Formal scrappage units, which are equipped to meet environmental guidelines, are limited to a few private players such as Mahindra Group, Tata Group and Toyota. To attract more formal players, the government may need to offer incentives. SIAM, too, has sought incentives in the form of 50% tax rebate in GST, road tax and registration charges. But, the experience of other countries suggests that such a policy may not be fiscally prudent. In March 2015, ICCT released a survey that analysed policies implemented by different regions across the world. Post the 2008 sub-prime crisis, the wildly popular Cash for Clunkers programme was launched in 2009 by the US government with an initial budget of $1 billion. Vehicles less than 25-years-old were targeted and a one-time payment of either $3,500 or $4,500 was given to owners. But the initial budget was exhausted in the first week. Eventually $2.85 billion was spent and a total of nearly 680,000 vehicles were scrapped and replaced.

In March 2015, ICCT released a survey that analysed policies implemented by different regions across the world. Post the 2008 sub-prime crisis, the wildly popular Cash for Clunkers programme was launched in 2009 by the US government with an initial budget of $1 billion. Vehicles less than 25-years-old were targeted and a one-time payment of either $3,500 or $4,500 was given to owners. But the initial budget was exhausted in the first week. Eventually $2.85 billion was spent and a total of nearly 680,000 vehicles were scrapped and replaced.

Under Germany’s 2019 ‘Scrappage Bonus’ programme, light-duty vehicle owners were eligible for a one-time bonus of $3,500 on purchase of a new vehicle. The programme was to last till December 2009, but its entire budget of $7 billion was exhausted by September 2009, after having subsidised 2 million vehicles.

China’s first national scrappage subsidy programme was also initiated around mid-2009. The year-long programme offered subsidies ranging from $490 to $980 per scrapped vehicle. Due to poor consumer response, the government revised the subsidy from $980 to $2,940. The programme was extended to end-2010 and a total of $1.04 billion was spent on subsidy for 459,000 vehicles. Since, several municipalities in China have developed their own scrappage subsidy programme, but Beijing has emerged as the most successful at retiring end-of-life vehicles.

While national level programmes were discontinued, the countries continue to have complementary policies in place. The United States has stringent vehicle emission regulations, Germany has rules with respect to low emission zones and the Chinese government has mandatory age limit for vehicles.

In order to get demand rolling, India needs a more efficient scrappage system than it has now. But, going by the experience of other countries, helping the already functioning informal units to become more efficient seems a better option than an expensive incentive-based policy to attract formal players.

India’s junkyard awaits a smart policy

An efficient scrappage system can provide a boost to the auto industry and reduce pollution levels. But, it will be prohibitively expensive

Junkyard

Junkyard