Just a few short months ago I was bullish and penning my thoughts on the fear and psychology of bear markets. Little did I know, I would find myself writing about the opposite situation in such a short space of time. However, since those dark days of late March, the US equity market has rallied some 47%, other world markets nearly 38%, and even my much beloved emerging markets have turned in a 36% increase.

Just a few short months ago I was bullish and penning my thoughts on the fear and psychology of bear markets. Little did I know, I would find myself writing about the opposite situation in such a short space of time. However, since those dark days of late March, the US equity market has rallied some 47%, other world markets nearly 38%, and even my much beloved emerging markets have turned in a 36% increase.

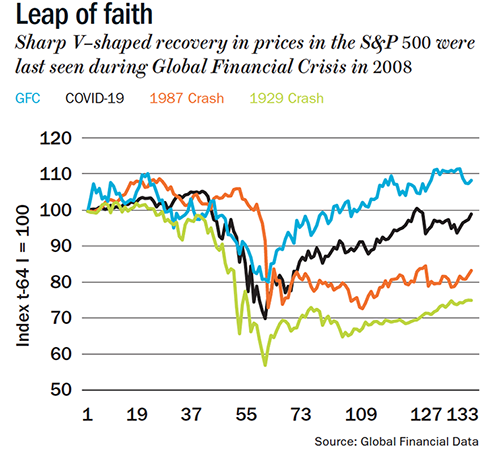

Both the speed and scale of the US equity market decline and its rebound are rare events. In terms of the scale of decline and its speed, I have been able to find only a few other examples to offer as comparison to determine whether sharp declines are often followed by sharp rebounds. We saw similar declines over roughly the same time period in 1987 (obviously, October 1987), late in the Global Financial Crisis (December 2008), and early on during the Great Depression (November 1929). Of the three, only the Global Financial Crisis experienced a similar, very sharp recovery (and this ignores the fact that the market had already declined by 40% before the period of the very sharp sell-off).

It would, of course, be foolhardy in the extreme to extrapolate any conclusions from a sample size of just these events. But, I do believe I can say that a market does not have the divine right to display a sharp bounce-back after a sharp decline.

As is often the case, it now appears as though most market participants – I hesitate to use the term investors – are back in full swing with Ian Dury and The Blockheads’ Reasons To Be Cheerful echoing through their heads. I have written countless times over the years that overoptimism and overconfidence are a particularly heady and potently dangerous combination because they lead to the overestimation of return and the underestimation of risk. This combination strikes me as the best description of our current juncture.

It is really the latter trait – the lack of appreciation for risk – that will be the subject of this short missive. One of my favorite definitions of risk comes from Elroy Dimson of Cambridge University who noted, “Risk means more things can happen than will happen.” I find this helps reinforce the unknowable nature of the future and highlights that history is just a series of discrete branches on a much larger tree.

So, when I look at a very sharp recovery (See: Leap of faith) like the one we have all just observed, I can’t help but wonder if the world has forgotten about risk. It appears to be as if the US equity market in particular has priced in a truly Panglossian future, where everything is for the best in the best of all possible worlds.

So, when I look at a very sharp recovery (See: Leap of faith) like the one we have all just observed, I can’t help but wonder if the world has forgotten about risk. It appears to be as if the US equity market in particular has priced in a truly Panglossian future, where everything is for the best in the best of all possible worlds.

False positive

It is certainly true in theory that the stock market is meant to be a forward-looking device, capable of seeing through short-term issues. However, as an erudite soul once opined, “In theory, there is no difference between theory and practice. But, in practice, there is.” History teaches us that the market is usually a master of double-counting, attaching peak multiples to peak earnings and trough multiples to trough earnings.

For instance, in 1929 the US market P/E was 37% above its long-term average and earnings relative to 10-year earnings were 46% above their normal level. Similarly in 2000, the market P/E was 98% above its average, and earnings relative to 10-year average earnings were 37% above their normal level, indicating peak multiples on peak earnings. In comparison, in 1932, the market was just 64% of its average valuation, and earnings relative to their 10-year average level were just 54% of the average — trough multiples on trough P/Es.

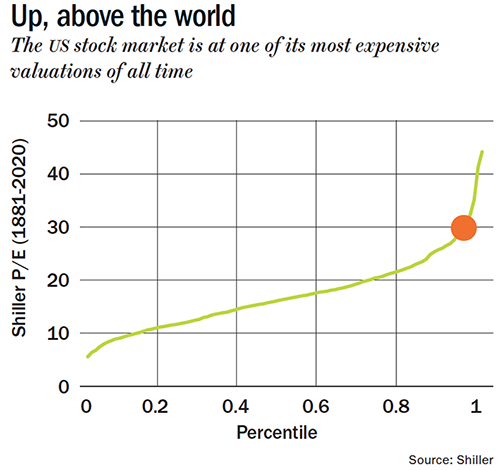

Today, we see something different. Valuations on a Shiller P/E basis (See: Up, above the world) are in the 95th percentile (right up there in terms of one of the most expensive markets of all time), and economic growth measured as real GDP is in the fourth percentile based on pretty generous assessments of this year’s growth (which is one of the worst economic outcomes we have ever seen).

Perhaps, today’s market is truly “looking over the valley,” but it would be one of the few times in history when Mr. Market managed such foresight. Even if this is the case, the certainty with which a V-shaped recovery is being priced in, reflects a potentially dangerous level of overconfidence.

Now, to be clear, I have no idea what the shape of any recovery is going to be. How one begins to choose between W, L, swoosh (like the Nike symbol, apparently), or perhaps something more exotic from the Cyrillic alphabet remains beyond my ken.

However, it strikes me that it is likely to be much harder to get the US economy going again post COVID-19 than the market is implying. I don’t think for one second that it is simply a matter of flicking a switch back to the “On” position, which makes the perhaps one of the least likely outcomes.

The shape of the recovery ultimately depends on a large number of frankly unknowable things, such as a household’s ability and willingness to spend. In February, there were six million unemployed people in the US; today, there are more than 30 million! One study from the University of Chicago estimates that up to 40% of the layoffs related to COVID-19 could be permanent! If these projections are even close to accurate about the permanent nature of some of these losses, then households may be unable or unwilling to spend as they had before the virus struck. The impact on business in terms of bankruptcies and lower investment will also be key. It is easy to imagine that in the wake of the virus, entrepreneurs may be hesitant to start new businesses, which are often said to be the lifeblood of the US economy (See: Out of sync). Sadly, many businesses will have failed due to the effects of the pandemic, and even those that do survive may find their animal spirits dampened significantly.

The impact on business in terms of bankruptcies and lower investment will also be key. It is easy to imagine that in the wake of the virus, entrepreneurs may be hesitant to start new businesses, which are often said to be the lifeblood of the US economy (See: Out of sync). Sadly, many businesses will have failed due to the effects of the pandemic, and even those that do survive may find their animal spirits dampened significantly.

I am certainly not in the business of trying to second-guess how the future will unfold, but I do know that anyone claiming certainty of foresight is likely to be sorely disappointed. And yet, Mr. Market appears to be doing exactly that.

Blind faith

Howard Marks of Oaktree Capital often talks about there being two kinds of investors. The two groups can be broadly distinguished by their attitudes towards the future. The first camp is best described as “I know” investors. They think that knowledge of the future course of events such as growth and interest rates is vital to investing. They are confident that such knowledge is attainable, and they “know” they can forecast accurately. They are very comfortable investing on the basis of their views. They freely admit that others will be trying to do the same thing, but their insight is better: it is their edge. Such investors are very popular at dinner parties because they will chatter on about pretty much any subject.

In contrast, the second group of investors studied at the “I don’t know” school. They hold some very different beliefs about the way you should approach investing. They believe you can’t know the future, and, in fact, you don’t need to know the future in order to invest. Driven by this explicit embrace of uncertainty, they insist on a margin of safety when investing: valuation is front and foremost in their approach. This group is not particularly popular at dinner parties (or maybe it’s just me) as the frequent refrain of “I don’t know” in response to questions is not amazingly stimulating on the conversation front.

As should be obvious, I firmly identify with the “I don’t know” school, having already stated that I don’t know several times in response to some very important questions raised earlier in this missive. Naturally, when Mr. Market acts with what looks to me like extreme certainty, I get nervous. Even if my caution is completely misplaced, it does not change my view that the US market has priced in all the good news it possibly can, suggesting very little upside from a fundamental point of view.

Now, of course many will argue that focusing on the fundamentals is a quaint, old fashioned idea just as they had done during all the great bubbles we have witnessed and studied. They will argue that this is all about the Fed and then blather on about “liquidity creation,” usually in the vaguest of hand-waving fashion.

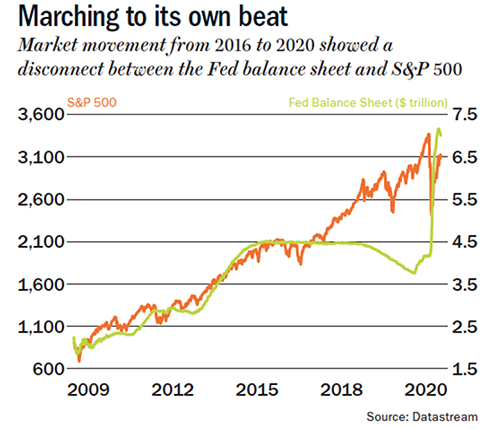

I find it strange that proponents of this narrative didn’t speak up when the S&P soared during the four years from 2016 to 2020 (See: Marching to its own beat), when the Fed’s balance sheet was either flat or shrinking.

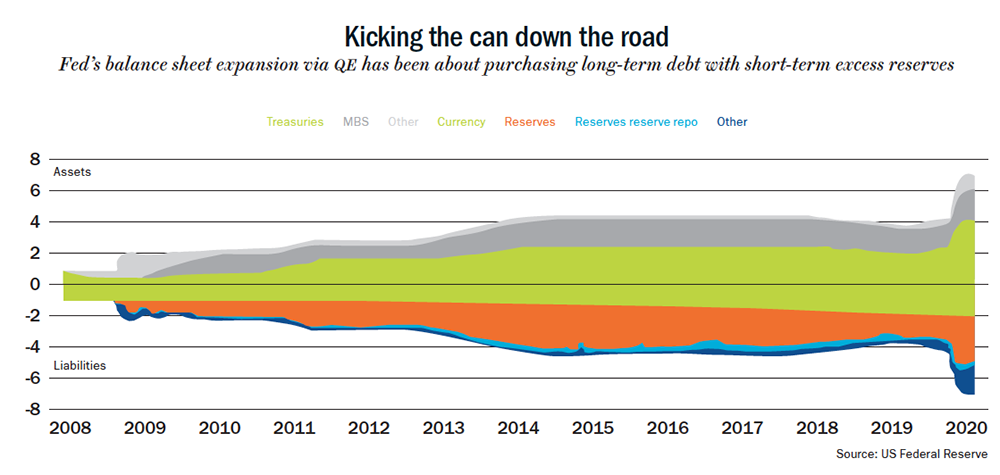

From a fundamental (there I go again, set in my old ways) perspective, it is tricky to argue for any direct linkage from the Fed’s balance sheet to equities. Most of the expansion of the balance sheet has been due to the various QE programs. And QE is really just a maturity transformation (i.e., purchasing long-term debt and replacing it with the ultimate form of short-term debt, excess reserves). The clue is in the term “balance sheet”: for every asset there must be a liability and vice versa.

To provide some context, the following is a breakdown of the Fed’s QE programs through the years:

QE1: $2.3 trillion in assets. The Fed’s first QE program ran from January 2009 to August 2010 (See: Kicking the can down the road). The cornerstone of this program was the purchase of $1.25 trillion in mortgage-backed securities (MBS)

QE1: $2.3 trillion in assets. The Fed’s first QE program ran from January 2009 to August 2010 (See: Kicking the can down the road). The cornerstone of this program was the purchase of $1.25 trillion in mortgage-backed securities (MBS)- QE2: $2.9 trillion in assets. The second QE program ran from November 2010 to June 2011 and included purchases of $600 billion in longer-term Treasury securities

- Operation Twist (Maturity Extension Program). To further decrease long-term rates, the Fed used the proceeds from its maturing short-term Treasury bills to purchase longer-term assets. These purchases, known as Operation Twist, did not expand the Fed’s balance sheet and were concluded in December 2012.

- QE3: $4.5 trillion in assets. Beginning in September 2012, the Fed began purchasing MBS at a rate of $40 billion/month. In January 2013, this was supplemented with the purchase of long-term Treasury securities at a rate of $45 billion/month. Both programs were concluded in October 2014

- Balance Sheet Normalization Program: $3.7 trillion in assets. The Fed began to shrink its balance sheet in October 2017. Starting at an initial rate of $10 billion/month, the program called for a $10 billion/month increase every quarter, until a final reduction rate of $50 billion/month was reached.

- QE4: $7 trillion in assets. In October 2019, the Fed began purchasing Treasury bills at a rate of $60 billion/month to ease liquidity issues in overnight lending markets. On March 15, 2020, the Fed announced it would buy at least $500 billion in Treasury securities and $200 billion in government guaranteed MBS over “the coming months.” On March 25, it made the purchases open-ended in size. On June 10, the Fed said it would buy at least $80 billion/month in Treasuries and $40 billion in RMBS/CMBS. A raft of other measures was also announced but pale into insignificance in terms of the Fed’s balance sheet. U.S. Treasuries held outright account for 64% of the Fed’s assets, and MBS almost 30%.

It is very hard to see how maturity transformation should engender massive enthusiasm for equities. You might be sitting there reading this, screaming silently that I am a moron and that the missing link is interest rates. To wit, by performing QE, the Fed lowers the bond yield and, because this serves as the discount rate for other assets, it drives up the stock market.

I have several issues with this viewpoint. First, I am very skeptical of a clear link between bond yields and equity valuations. A little international perspective helps illustrate one of the reasons for my skepticism. Japan and Europe both have exceptionally low interest rates, mirroring the US, but they aren’t witnessing stock market valuations at nosebleed-inducing levels. Second, even if I accepted the link, there is the problem still that if the interest rate is low because growth is low, then the valuation is unchanged in a simple DDM framework. And third (and in my humble opinion the killer blow for this argument), QE hasn’t actually managed to lower bond yields, which truly emasculates the argument. All three of the completed cycles of QE have actually ended with yields higher than they were when the QE began! (See: Mission unaccomplished)

I have several issues with this viewpoint. First, I am very skeptical of a clear link between bond yields and equity valuations. A little international perspective helps illustrate one of the reasons for my skepticism. Japan and Europe both have exceptionally low interest rates, mirroring the US, but they aren’t witnessing stock market valuations at nosebleed-inducing levels. Second, even if I accepted the link, there is the problem still that if the interest rate is low because growth is low, then the valuation is unchanged in a simple DDM framework. And third (and in my humble opinion the killer blow for this argument), QE hasn’t actually managed to lower bond yields, which truly emasculates the argument. All three of the completed cycles of QE have actually ended with yields higher than they were when the QE began! (See: Mission unaccomplished)

This all suggests there is a good chance that the Fed balance sheet and the S&P 500 is just the result of spurious correlation. That is to say that two series happen to move together despite their being no underlying connection between them. When one studies statistics (as I did many, many moons ago), one is repeatedly taught that correlation does not equal causation for this very reason. One of my personal favorite examples (See: Fiction stranger than fact), comes from Tyler Vigen and shows a 94.7% correlation between per capita cheese consumption and the number of people who die by becoming tangled in their bedsheets!

Sadly, we humans are prone to love a story. Hence, when we see a correlation (even a spurious one), it is tempting to make up a story to explain the relationship. I think this is exactly what we see when people start talking about equities, the Fed, and “liquidity creation.”

I don’t think there is any fundamental relationship between the stock market and the Fed’s actions, I would suggest that this is either ex post justification or, at best, a driver of the ever-slippery concept of sentiment.

One final word of warning when it comes to markets and authorities. I am old enough to have been around when the Japanese engaged in their price-keeping operations from 1992 to 1993 with the aim of keeping the Nikkei 225 above a certain level. These attempts failed both in the short term and the long term, and serve as a salutary tale as to the limits on the ability of official bodies to control prices in even the most direct fashion.

In conclusion, it appears to me, at least, that the US stock market has priced in a truly Panglossian outcome with essentially a 100% probability. It is as if the market is taking a (good) tail risk and pricing it as the central case. This strikes me as extreme overconfidence, especially given the vast and imponderable questions that define today’s environment.

The current dominant narrative seems to center on the irrelevance of these questions and favors a “Fed-based” explanation. I think this is dangerous. Ignoring the fundamentals is rarely a good strategy for the longer term, and the evidence seems at odds with the notion of the “Fed” explanation, suggesting this is more ex post justification and not a genuine driver of returns.

Investing is always about making decisions while under a cloud of uncertainty. It is how one deals with the uncertainty that distinguishes the long-term value-based investors from the rest. Rather than acting as if the uncertainty doesn’t exist (the current fad), the value investor embraces it and demands a margin of safety to reflect the unknown. There is no margin of safety in the pricing of the US stocks today. Voltaire observed, “Doubt is not a pleasant condition, but certainty is absurd.” The US stock market appears to be absurd.

This is an excerpt from GMO’s August 2020 White Paper. You can read the complete version at WWW.GMO.COM. Copyright © 2020 by GMO LLC. All rights reserved.