How often does a promoter pledge a part of his stake to increase his holding in the company? It seems counter-intuitive. But that’s exactly what the promoters of Parag Milk Foods did. All hell broke loose when a persistent query by an analyst during the Q3FY20 earnings call saw the promoter revealing that a loan was taken to increase their stake but refused to reveal the source of funding. On being probed further by analysts, Devendra Shah, executive chairman, said, “It’s a total commercial bank, don’t worry about that.”

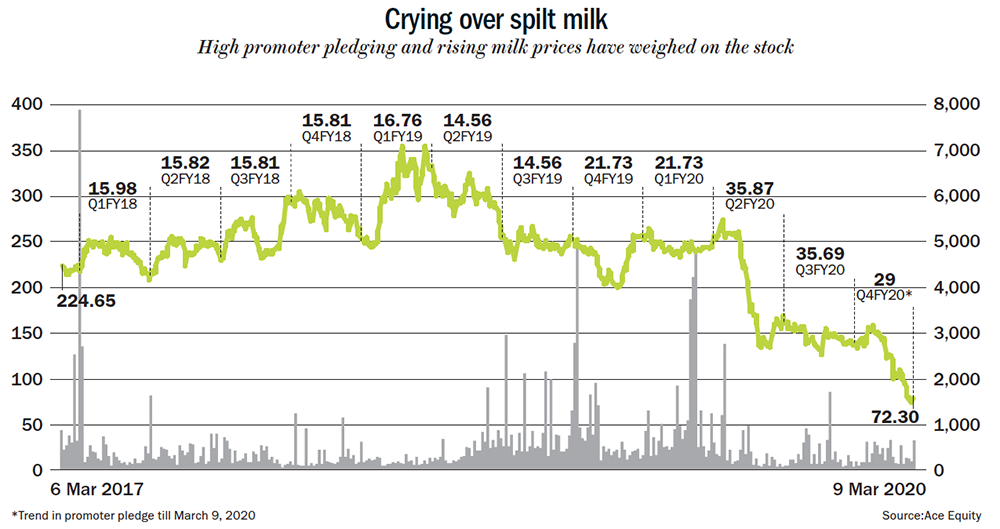

But the response was hardly convincing. The stock price, which was already under pressure because of the rise in milk prices (pivotal ingredient for value-added products), collapsed after the earnings call on February 11, plunging 37% to its all-time low of Rs.74.65 on March 2 (See: Crying over spilt milk).

But the response was hardly convincing. The stock price, which was already under pressure because of the rise in milk prices (pivotal ingredient for value-added products), collapsed after the earnings call on February 11, plunging 37% to its all-time low of Rs.74.65 on March 2 (See: Crying over spilt milk).

The sell-off began with Religare Invesco Asset Management dumping shares worth Rs.127 million on February 11, followed by the Government Pension Fund Global of Norges Bank, which offloaded shares worth Rs.74 million and Rs.56 million on the BSE and NSE on February 12. “A lot of institutional investors struck block deals after the earnings call. I am actually a little surprised at the number of exits,” says a veteran analyst, who has been tracking the stock, since its listing in May 2016.

Facing a precarious situation, the promoter issued a clarification on March 2. “The promoters have repaid Rs.310 million of the original loan taken from Kotak Mahindra Investments and the outstanding loan stands at Rs.330 million as on March 2, 2020,” said the company in a filing to the exchanges. The statement said the outstanding amount will be repaid within 90 days and, subsequently, the pledged shares would be revoked.

In fact, Shah had first pledged his stake, beginning June 2017, when the stock traded between Rs.216 to Rs.248. In his defense, Shah states, “We wanted to increase the shareholding in the company post dilution because of IPO and therefore took a loan to increase the stake through creeping acquisition.” As of March 9, the promoters hold 46.20% (38,861,435 shares) stake, of which 29% (11,143,000 shares) is pledged to lenders.

In a November 2019 Business Standard report, Shah said the promoter group was looking to bring down its pledged shares by 20% and increase the overall holding to 51% by purchasing 4.2 million shares from the open market over the next few quarters. In fact, when the promoter bought 200,000 shares from the market on November 15, the stock rose 14% to Rs.145.

Well, better late than never. But the promoter’s clarification failed to revive investor confidence and the stock price hit a new all-time intra-day low of Rs.62.40 on March 6. “Pledging of stock was a bad decision but not a malafide one. It’s risky but Indian promoters are risk takers,” says the analyst quoted above.

Tough Times

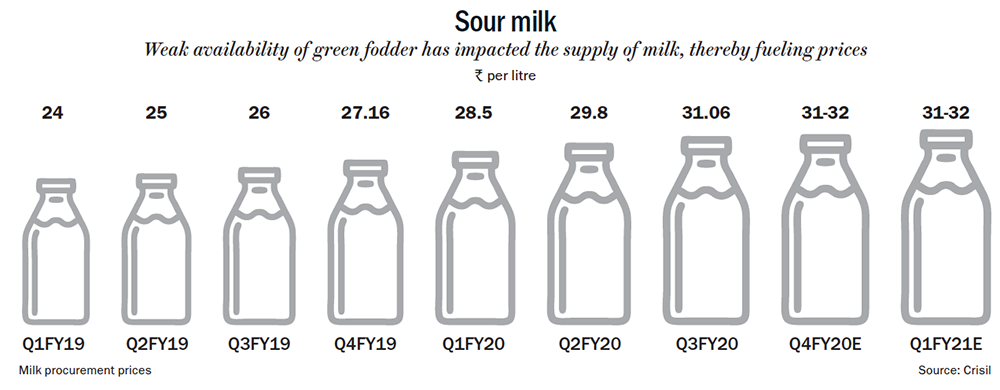

While the issue of pledged shares continues to haunt Parag, the company is also going through a tough cyclical period. The current fiscal has been a rough year for dairy companies with milk prices surging 19% year-on-year (YoY) between April and December 2019 (See: Sour milk). Crisil estimates that “for the full fiscal, inflation is expected to be similar, at 18-20%.” This has clearly impacted the bottomline of Parag.

Over the past nine months, as the cost of raw material went up by 14% YoY to Rs.12.33 billion, operating profit fell 1.22% to Rs.1.70 billion. Since 67.5% of the revenue comes from milk products including cheese and ghee, the profitability has been impacted adversely. “Our interactions with stakeholders indicate that prices of key value-added products such as butter, ghee and skimmed milk powder (SMP) are expected to rise 5% by the end of this fiscal,” states a Crisil report dated February 2020 on the dairy sector.

Over the past nine months, as the cost of raw material went up by 14% YoY to Rs.12.33 billion, operating profit fell 1.22% to Rs.1.70 billion. Since 67.5% of the revenue comes from milk products including cheese and ghee, the profitability has been impacted adversely. “Our interactions with stakeholders indicate that prices of key value-added products such as butter, ghee and skimmed milk powder (SMP) are expected to rise 5% by the end of this fiscal,” states a Crisil report dated February 2020 on the dairy sector.

The dairy market in India is highly competitive with the price of milk being a defining factor. Parag isn’t the only one to bear the brunt. In 2019, Prabhat Dairy sold its milk processing business to global dairy major Lactalis. Similarly, MNC major Danone exited its dairy business to focus on nutrition products in 2018. Low prices and availability of milk may have prompted several global and domestic players to make inroads in the dairy sector, but tough competition and rising milk prices have played spoilsport.

Analysts believe the rise in prices of milk makes it difficult for private companies to compete with big co-operatives. “Amul doesn’t increase product prices even if milk rates go up as it is not under pressure to make profit. But a private player has to hike prices else margins get squeezed,” says an analyst. He also states that if an item is priced at a premium compared to Amul, it’s unlikely to go off the shelf as the milk co-operative has stronger brand recognition and product quality compared with private players. “Structurally dairy industry is difficult to operate because large players such as Amul and Mother Dairy have the largest collection network, operate with low profit motive and high farmer welfare motive,” says Prateek Giri, equity research associate, Emerge Capital.

However, Ankur Bisen, senior vice president (retail) at consulting firm Technopak Advisors believes Parag is trying to create a niche for itself in the premium category and doesn’t directly compete with Amul. For instance, Amul cow ghee is priced at Rs.515, whereas Gowardhan’s costs Rs.595. “Amul has wider availability, a strong supply chain and large scale. One can’t compete with Amul in the mass market and hence Parag is present in the premium end of the market,” says Bisen.

Branded Player

Keeping aside recent difficulties and structural problems, Parag has emerged as a formidable brand over the years. The dairy firm uses only cow milk and sources nearly 80% of it directly from farmers, village collection and chilling centres. The company, which started operations in 1992 near Pune, has a network of more than 200,000 farmers spanning across 29 districts in western and southern states. With seven brands — Gowardhan, Go, Pride of Cows, Topp Up, Avvatar and Slurp — Parag has a pan-India presence through 19 depots, 140 super stockists and 3,000 distributors. The company claims it’s the second biggest cheese player in India with 35% market share and is a leader in cow ghee category. Its financial performance was impressive, too. Between FY10 and FY19, sales compounded at 19% to Rs.23.46 billion, while net profit grew annually at 34% to Rs.1.14 billion.

The brokerages were also gung-ho about the company’s prospects till a few months ago. Analysts at Elara Capital had written in a May 2019 report: “Parag has reported high growth by expanding into North & East India while keeping working capital under control. As the company reduces SMP salience and increases liquid milk or VAD (value added dairy products) salience in FY20, margin should move up to 10%.” Analysts at Motilal Oswal Securities had a ‘buy’ rating on the stock when it was trading at Rs.207 in August last year. “Raw material inflation impacted the company’s performance during the quarter; however, measures taken by the company (price hike and reduction in discounts) coupled with no further inflation in raw milk prices should benefit the operating performance in the coming quarters,” said their report.

But the company’s recent performance hasn’t matched expectation. Ebitda margin has dropped from 10.27% in 9MFY19 to 9.16% in 9MFY20. Profit has been hit despite price hikes by the company. However, Shah states, “Our brand strength, distribution network, cost rationalisation and productivity measures have enabled us to manage the tough industry situation and maintain Ebitda margin at 9%.”

Value trap?

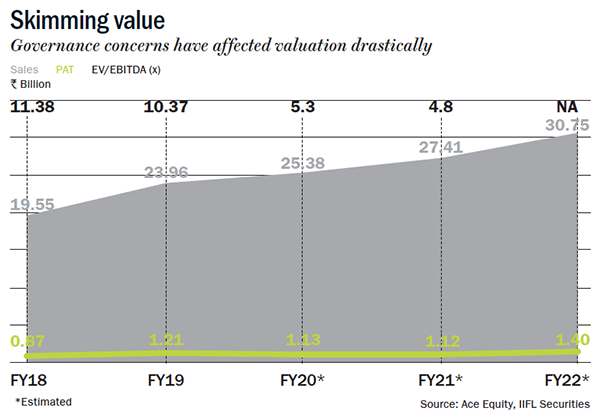

The stock which closed day one of listing at Rs.247, up 15% from its offer price of Rs.215, hit a high of Rs.368 in May 2018, but has since come off by 80%. Incidentally, noted investor Ashish Kacholia, who held 1.70% stake (1.43 million shares) since June 2016, had marginally pared his holding to 1.49% (1.25 million shares) as of December 2018. Since then, he seems to have exited the stock completely. At the current level of Rs.72, it trades at 8x estimated FY21 earnings and from a book value perspective, the stock is trading at 32% discount to the book value of Rs.106. Even on estimated FY21 EV/Ebidta basis, it trades at 4.8x, given its manageable debt (See: Skimming value). In comparison, Parag’s peers such as Hatsun Agro and Heritage (excluding the value of FRL stake) are valued at 77x and 15x estimated FY21 earnings, respectively. When asked about the loss of investor confidence despite its relatively low debt, Shah says, “Investor sentiment is associated to a lot of factors including macro-economic scenario and bias towards blue-chips, and we are not aware of any other factors concerning them as of now.”

Percy Panthaki, analyst at IIFL Securities, states that the fall in the stock price has made Parag attractive and that price hikes will eventually drive topline growth. “With inflation likely to persist till the next flush season, companies have taken more price increases in Q4FY20, which is likely to drive topline growth in the near-term,” opines Panthaki in his report.

Percy Panthaki, analyst at IIFL Securities, states that the fall in the stock price has made Parag attractive and that price hikes will eventually drive topline growth. “With inflation likely to persist till the next flush season, companies have taken more price increases in Q4FY20, which is likely to drive topline growth in the near-term,” opines Panthaki in his report.

While high milk prices are just the tip of the iceberg, the wounds run deep for the company. Another major concern for investors is trade receivables. “They have high receivables as percentage of sales and are taking write offs for the same. Moreover, this industry has a tarnished image due to what happened in Kwality and other few players. The balance sheet of Parag signals something similar if one looks at loans and advances in the current assets segment of the balance sheet. This has added fuel to the fear among investors,” says Giri. His caution isn’t unfounded. Trade receivables rose from Rs.1.71 billion in FY17 and Rs.2.51 billion in FY18 to Rs.2.78 billion in March 2019, which is 9% of its annual sales. Shah states that they have decreased creditor days by 10 days while increasing receivable days by five. “As a result of this, working capital cycle stood at 90 days. Since this is a temporary situation due to sequential increase in raw milk prices and tighter availability of milk, the situation will normalise once milk availability is normal and our working capital cycle will come back to earlier levels,” says Shah.

Giri believes a brand needs to constantly generate cash flow for investors to value it highly. “A brand makes sense only if it helps generate cash, which is not the case with Parag. So, it cannot be said that it is undervalued because determining valuation with balance sheet uncertainty (loans and advances) is very difficult,” he asserts. Elara Capital in an update stated that the free cash flow (FCF) for FY20 is expected at around Rs.600-650 million (Rs.330 million in H1FY20) and “milk subsidy receivables Rs.210 million if not received in FY20 could lead to an increase in provisions by a significant extent.” “If these concerns are addressed, upside in Parag could be higher, although it comes with a higher risk,” mentions Panthaki. Another red flag is that the new CEO Venkat Shankar was absent from the recent earnings call. The management shrugged off the question on Shankar’s absence, stating that he could not attend as he was unwell. In fact, the company saw its top hire Vimal Agarwal, the then-chief financial officer quit in July 2019. Given that corporate governance has been the bane of small and mid-cap stocks, unless the promoters come clean on investor concerns, the stock seems unlikely to rerate in a hurry.