On a scorching afternoon in the summer of 2024, a cluster of 60 data centres known as ‘Data Centre Alley’ near Washington DC suddenly disconnected from the power grid. Within seconds, demand equivalent to a city vanished, forcing local officials to scale back output from power plants and avert a blackout in the region.

The incident served as a warning of how sudden shifts in power demand from data hubs can destabilise even advanced grids. As India races to build its own data centre clusters from Navi Mumbai to Visakhapatnam, such highly concentrated energy demand can strain the country’s grid, already grappling with ageing infrastructure, renewable integration and transmission bottlenecks.

“If regulators and data-centre developers fail to analyse the required capacity and don’t build the required transmission lines, it could lead to major blackouts, as India operates on a unified national grid,” says energy-market analyst Akkenaguntla Karthik.

Energy Dilemma

India’s data centres are poised for significant expansion, driven by 800mn internet users, rapid adoption of AI and increasing reliance on cloud services. The sector’s capacity is expected to grow dramatically from 1GW in 2024 to 9GW by 2030 at a compounded annual growth rate (CAGR) of 40%.

The push began in 2018 with the RBI’s directive requiring all payment data to be stored domestically, followed by proposals in the Personal Data Protection Bill (2019). Together, such regulatory changes are forcing global giants to create more capacity within India’s borders, explains Narendra Sen, founder of NeevCloud, an AI cloud-service provider. “With new data-protection rules and localisation requirements, global players like Google, Amazon and Microsoft are making substantial investments in India,” says Sen.

Google, for instance, announced a massive $15bn AI data hub in Andhra Pradesh, which is its biggest investment in India till date. In January, Amazon Web Services (AWS)—the cloud-computing arm of the global e-commerce conglomerate—said it would invest $8.3bn to expand its Mumbai cloud region. Social-media giant Meta, too, is preparing to make multi-billion-dollar investments in a subsea cable project.

It’s not just global tech giants who are driving this boom. Indian corporate heavyweights like Reliance Industries, AdaniConneX, Tata Consultancy Services and Bharti Airtel are also investing aggressively in the sector. According to a report by professional-services firm Colliers India, this expansion will involve a total investment of $22bn by 2030.

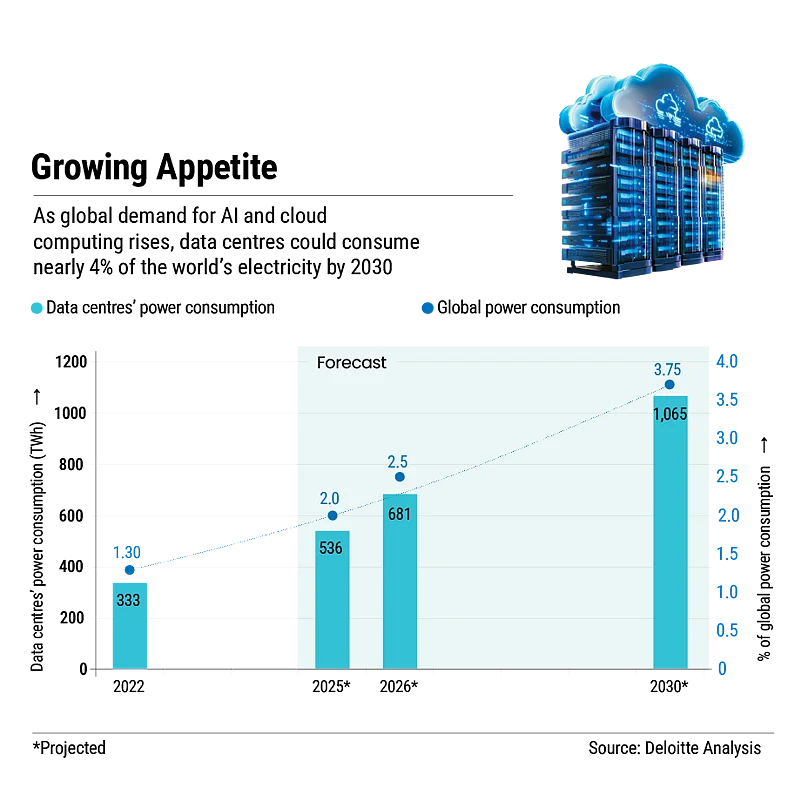

However, despite such hefty investment projections by Indian and international giants, the industry faces a serious challenge, namely, power supply, as the sector is set to increase its share of power consumption from less than 0.5% at present to around 3% by 2030.

Power Crunch

Traditional data centres in India are used for less computationally intense purposes such as streaming movies, retrieving website data and storing information. However, the arrival of AI has changed this equation. AI workloads are highly computationally intensive and depend on power-hungry graphics processing units (GPUs).

“Data centres consume more electricity than many of our cities. So, more queries mean more analysis and that translates into more power consumption,” says Sen.

Energy is needed not just for running the GPUs, but also for cooling them. For instance, if a GPU server consumes 100 units of power to operate, it may need another 80 units to keep it cool.

Such massive and continuous power demand creates additional strain on local electricity grids, especially in regions where data centres are clustered together. India’s key data-centre hubs Mumbai (61), Hyderabad (33), Delhi-NCR (31), Bengaluru (31) and Chennai (30) are already feeling the pressure.

“With so many data centres coming up in these regions, the load on transmission lines and substations has become extremely high. This is the same phenomenon seen in Ashburn, US and in Singapore, where rapid concentration of data centres ran up against local grid constraints,” says Sunil Gupta, managing director and chief executive at data centre and cloud-solutions provider Yotta.

However, India’s power grid was not designed to handle the round-the-clock, high-load demand that modern data centres generate. Therefore, it remains constrained by a lack of adequate transmission infrastructure to evacuate power from renewable energy-generation hubs like Gujarat and Rajasthan to demand centres like Vishakhapatnam.

This is further complicated by continued implementation delays. “In 2024–25, 8,830 circuit kilometres [ckm] of new transmission lines were commissioned against a target of 15,253ckm, representing a 42% gap, with Inter-State Transmission System [ISTS] additions at their lowest in a decade,” notes a report by the Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis and JMK Research, a consulting firm.

When questioned in Parliament about the delays, Shripad Naik, Union Minister of State for Power, admitted that 14 ISTS projects have faced delays due to right-of-way issues. Eight of the 14 affected projects belong to the Power Grid Corporation of India, two projects each to Adani and Sterlite and one each to Tata Power and ReNew.

“Transmission and distribution is the biggest challenge today. Upgrading that infrastructure will require large investments by the utility, and these could either reduce power availability for local users or lead to higher tariffs as the extra capex is passed on to consumers,” says Gupta.

Clean Energy Paradox

The obvious answer to the power conundrum facing the industry is to set up captive power plants, as has been demonstrated in other power-hungry sectors such as aluminium smelting and cement manufacturing. Globally, this is the route most favoured by AI giants, with an added emphasis on green technologies.

Google, Amazon, Microsoft and Nvidia are backing ventures in advanced nuclear, geothermal, hydrogen and large-scale renewables to meet their massive electricity needs. Google has invested over $800mn in clean-energy firm Intersect Power, while Amazon supports small modular reactor start-up X-Energy and Nvidia has opted for US-based nuclear-energy company TerraPower.

Some headway has already been made in this direction in India too. For example, in February this year, Nxtra, the data-centre unit of telecom major Bharti Airtel, announced an agreement with renewable-energy developers AmpIn Energy and Amplus Energy to set up captive solar and wind power plants of 48MW direct current and 24.3MW for its data centres in Tamil Nadu, Uttar Pradesh and Odisha.

Similarly, AdaniConneX, a data-centre solutions provider and a joint venture between Adani Enterprises and EdgeConneX, has established sustainability-linked financing to raise $1.44bn to fund its renewable-powered data centres.

However, despite their green tag, most such green data centres are able to procure only 25–30% of their power requirements from renewables. This, says NeevCloud’s Sen, is because renewable power generation is time-bound and weather-dependent, while data centres require a continuous and uninterrupted supply.

“We secure long-term energy partnerships, typically 15–25 years, to ensure energy security, which is absolutely vital. Without guaranteed, continuous power, you simply can’t run AI or cloud infrastructure,” says Sen.

Given that only 25–30% of energy consumption of the industry is from green power, major players are exploring off-grid solutions, such as on-campus and captive plants, that directly feed the data centre without going through the distribution network. “These models are gaining traction in other parts of the world, but in India, whether such off-grid setups are fully allowed under current regulations remains unclear,” says Yotta’s Gupta. NeevCloud is also investing in battery energy storage systems.

Wired for Growth

To keep pace with the surge in AI and data centre requirements, India needs to start ramping up its power infrastructure. Experts say grid upgrades must be prioritised through accelerated investments in transmission corridors that connect renewable-rich states with high-demand urban clusters as new transmission infrastructure is essential to send power over long distances. “If those lines are congested or overloaded, power simply can’t flow. The government and regulators need to fast-track these approvals and investments,” says Karthik.

At the same time, experts say data centres should be mandated to source a higher share of firmed renewable power through hybrid solar-wind projects coupled with battery storage. But to achieve a 100% green set-up “India needs to bring in other clean, firm sources like small modular reactors”, says Karthik.

Regulators could also consider creating dedicated “green data-centre zones” with assured power supply, land and cooling infrastructure similar to industrial parks. Finally, improved demand forecasting, time-of-day tariffs and flexible contracts between utilities and operators can help balance round-the-clock digital power loads with India’s clean energy goals.