Buoyed by the steady growth of India’s automobile sector in the 2010s, Mumbai-based Mayank Nikam decided to pursue an industrial training institute (ITI) diploma in a related field. In 2012, he was hired by a leading auto-component manufacturer as a contract worker at its Nashik plant, where he was assigned to help produce injectors, a device that delivers fuel into the cylinders of an internal combustion engine (ICE).

For the next several years, things went smoothly. But in October 2021, Nikam and around 700 other workers were abruptly told not to report to work until further notice.

“It was not related to Covid,” Nikam claims. “Production had already resumed at the plant after the lockdown was lifted. They [the company] said the demand for diesel engine injectors was impacted partly because the government was promoting electric vehicles [EVs].”

While the company never publicly cited EVs as the reason, its annual report for financial year 2023–24 offered a telling glimpse of how it was grappling with a rapidly evolving market.

“Challenges brought in [by] a constant changing diesel market [and] policy changes are mitigated through transformational initiatives across all domains including people, process and localisation,” the report said, referring to its Nashik plant.

Though the company reversed its decision to lay off the workers in 2024 following a court order, the damage was done. The incident was enough to raise alarm among workers’ unions.

“If ICEs become obsolete due to EVs, the related supply chain will also be impacted,” says Surya Dev Tyagi, president of Hind Mazdoor Sabha, Haryana, a union that engages with workers in the automobile sector.

India’s auto sector employs 3.7mn people, contributes 7.1% to the country’s GDP and accounts for 49% of manufacturing GDP. But the shift toward EVs, critical for long-term sustainability, may leave behind a significant swathe of the workforce in the short to medium term.

Fewer Parts, Fewer Jobs?

According to the International Energy Agency, the transport sector contributes about 13% of India’s energy-related carbon-dioxide emissions, making it the second-largest emitter after the electricity and heat producer sectors (52.7%). Hence, transitioning to EVs is key to India’s 2070 net-zero target.

To push the shift, the government in the past 10 years has announced over ₹71,000 crore for EV promotion schemes, ranging from the Faster Adoption and Manufacturing of Hybrid and Electric Vehicles scheme to production-linked incentives for auto components and vehicle manufacturing.

Industry players have responded enthusiastically: Tata Motors and Mahindra & Mahindra have committed investments of ₹35,000 crore from financial year 2025–26 to financial year 2029–30 and ₹16,000 crore between financial year 2021–22 and financial year 2026–27, respectively.

But as India accelerates toward an electric future, the impending human cost of this transition remains under-addressed.

EV production requires significantly less labour than ICE manufacturing. Any major disruption in the sector has the potential to impact the overall economy in the long run.

Unlike ICE vehicles, which require more than 2,000 moving parts, EVs typically have only 20–25 parts in their drivetrains—the group of components that deliver mechanical power. This translates into fewer maintenance needs, greater reliability and lower operating costs. But it also spells fewer jobs for mechanics, technicians and factory workers.

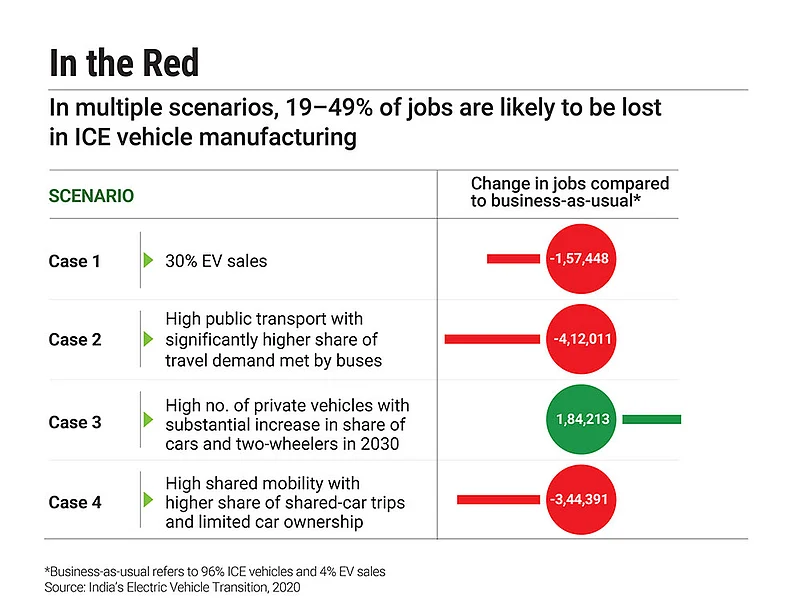

According to Saket Mehra, partner at Grant Thornton Bharat, a professional-services firm, EV assembly lines may need 30–40% fewer workers. Supporting this, a 2020 study by the think tank Council on Energy, Environment and Water found that ICE powertrain manufacturing—the system that propels the vehicle forward—creates 1.59 jobs per ₹1 crore of output, compared to just 0.35 jobs for EV powertrains.

EVs require a new component stack that demands advanced engineering capabilities. Most MSMEs neither possess this tech nor a skilled workforce

In an ICE vehicle, the powertrain comprises the engine, transmission, driveshaft, axles and differential. In EVs, it consists of an electric motor, battery and power electronics.

“Consider what goes away,” says Vilas Deshpande, co-founder and chief operating officer of Pune-based EV start-up Vayve. “The engine, which is complex to manufacture and labour-intensive, becomes redundant. That’s a significant labour loss.”

Original-equipment manufacturers (OEMs) have so far cushioned the blow by deploying shared platforms, that is, factories that produce ICE, hybrid and electric models side by side. “Every person working on our assembly lines is trained to work across both ICE and EV platforms,” says Rakesh Sen, director, sales, JSW MG Motor India.

But this balancing act won’t last forever. As manufacturers roll out EV-only models, reductions in manpower are inevitable.

“Highly automated plants may not see major changes. But labour-intensive lines will be affected. It varies by OEM,” says Deshpande.

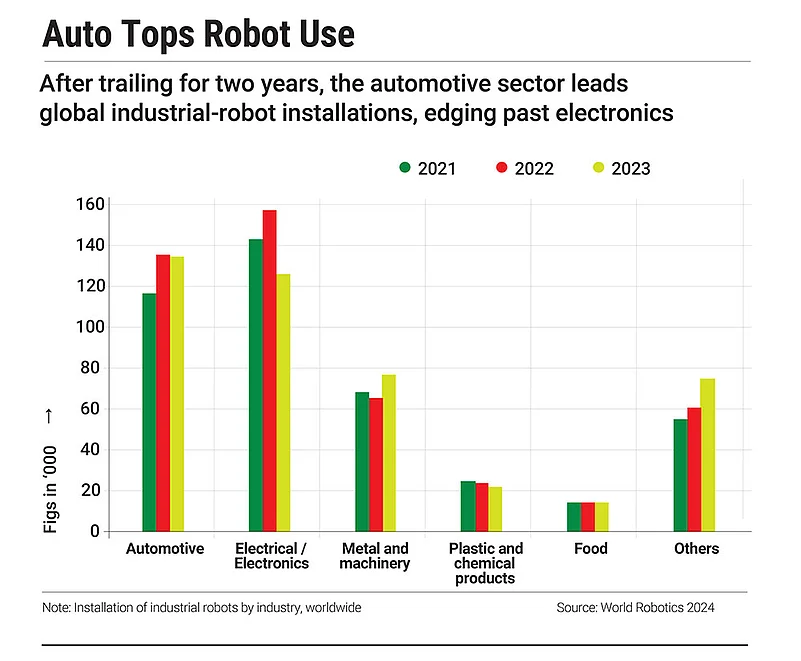

According to the World Robotics 2024 report, the automotive industry globally accounted for 30% of all industrial robot installations in 2023, making it the largest user of industrial robots.

The Hardest Blow

The biggest brunt of the EV transition may fall on the auto-component ecosystem, particularly MSMEs, which dominate ICE parts manufacturing and employ nearly half of India’s auto-sector workforce.

Unlike the relatively modern, automated lines of large OEMs, MSMEs have limited capital and low levels of automation. The technological shift, many fear, is going to be painful for the small-scale industry.

Components such as clutches, starter drives, gearboxes, radiators and exhaust systems—mainstays of ICE vehicles—will become irrelevant.

“Those with big setups and knowledge of [EV] technology will survive. Others will have to shut shops,” says Davinderpal Singh, owner of a Ghaziabad factory that manufactures starter drives for commercial vehicles. The starter drive is used to crank the engine and initiate fuel combustion.

Singh says his business from the three-wheeler segment has more than halved in the past 4–5 years. This comes as no surprise; Federation of Automobile Dealers Associations data shows that over 57% of all three-wheelers sold in financial year 2025 were electric.

Singh is now focusing on light and heavy commercial vehicles where EV penetration is under 1%. However, he is wary of the government’s EV push extending to heavier vehicles. Under the PM EDrive scheme, the centre has earmarked ₹500 crore for electrification in trucks, the segment on which Singh’s business now relies.

“We are the people with knowledge of mechanical parts that go into vehicles. EVs will require the know-how of electrical and electronics. How can small businesses shift to that,” Singh argues. EVs require an entirely new component stack that demands advanced engineering capabilities. Most MSMEs neither possess this tech nor a skilled workforce. They also remain outside the emerging EV value chain and may struggle to establish new linkages with OEMs.

According to Nikhil Anand Khurana, managing director and chief executive of Folks Motor, a hybrid electric-retrofit company, the problem isn’t just technological but structural. “EV manufacturing demands a reorientation of supply chains, certifications and production capabilities, which many MSMEs currently lack.”

Reskilling is Key

Despite the threat of job losses, EVs are opening new employment avenues, if workers can pivot in time. The Society of Indian Automobile Manufacturers estimates that India will need 2,00,000 skilled professionals in the EV sector to meet its 2030 target of 30% EV adoption. It pegs the talent investment requirement at ₹13,552 crore. However, the industry currently faces a 40–45% skill gap.

Skills needed for this industry don’t just relate to mechanical parts but extend from battery technology, which is a core part of any EV, to control systems and vehicle softwares. The sector is moving from labour intensity to skill intensity. “We don’t yet have enough trained professionals,” warns Shantanu Rooj, founder and chief executive of TeamLease EdTech, an employment-solutions firm.

While TeamLease EdTech has partnered with institutions like IIT Bhilai and Jain University to run courses in EV engineering, mechatronics and sustainability, the scale is modest. “Our EV MTech programme admits 20 students per batch,” Rooj says. “We’re only in the third semester, so placements haven’t even begun yet,”

To fill the growing skill gap, OEMs like Tata, Mahindra, Ather and Bajaj have begun setting up in-house training academies, while MG Motor is collaborating with academia.

But experts say this patchwork approach won’t be enough to reach the millions in need of reskilling. Those who act now—learning battery management and EV-specific repair—can future-proof their careers. But for the rest, time is running out.

“If we get something related to mechanical parts, only then we would get into this,” Singh says, referring to his plans of venturing into EV component manufacturing. “Otherwise, we will shut down and look for something else.”