I have worked with over 60 brands in my career. Brands mean a lot to consumers and every book or idea around the “No brands thought” has not worked or survived. Brands mean something to people and are a form of self-expression. Brands might be viewed as a long list of promises or thoughts. My learning is that every brand over the years has stood for three things—A, C, E—A for authenticity, C for consistency and E for energy.

If you go back to Ivory soap and the concept of branding introduced about 146 years ago, Ivory was a first in putting up posters outside wholesalers to bypass the wholesaler recommendation which came in exchange for high margins.

The days of Ivory and the next 60 years in branding were about product superiority. Product claims led to brand authenticity and consistency.

Cue the Celeb

As technology became widely available, product differences or the unique selling proposition was no longer unique. Then came the creative renaissance in the US with image taking over brand communication. Brands saw a host of celebrity endorsements. Brands used celebs to stand out in a crowded market and celebs were the first kind of influencers in the physical world.

Brands also used what I label “sources of authority” like a safe-cracker who endorsed a safe brand that he couldn’t crack. Vidal Sassoon, the famous British hairstylist, styled Mia Farrow’s hair on the sets of Rosemary’s Baby and was an overnight hit. He introduced the five-point geometry cut. This led to Vidal Sassoon launching his own range of shampoos in the ’70s and the range was bought by Procter and Gamble in the ’80s. So, the source of authority or influencer had created value through a new economic model.

Lux soap was a pioneer globally and in India for film-star endorsements. It started when Danny Danker, a J Walter Thompson (JWT) executive in Hollywood signed up Ginger Rogers as the Lux model. JWT and Unilever took this positioning global, and it is so in India even today.

Brands used celebs to stand out in a crowded market and celebs were the first kind of influencers in the physical world

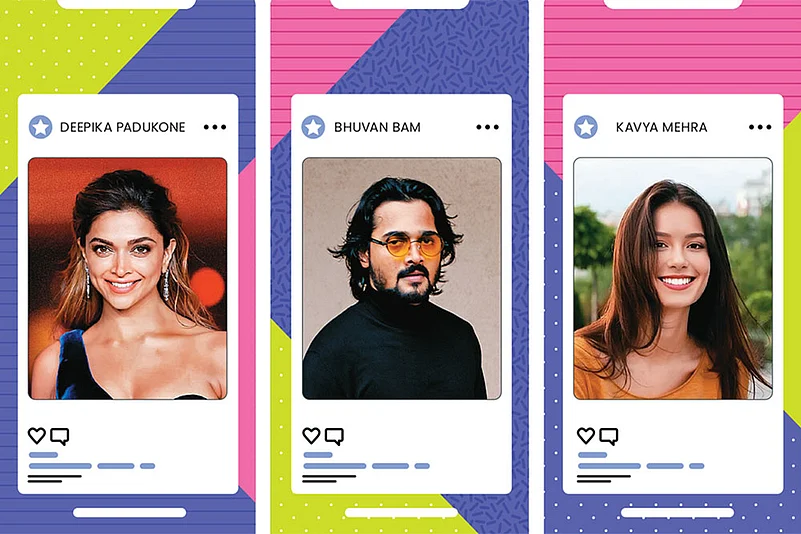

Leena Chitnis was the first star to endorse Lux soap. Meena Kumari, Sharmila Tagore, Zeenat Aman, Deepika Padukone and Shah Rukh Khan are other endorsers. This was the selling of a dream to the middle-class and lower-middle-class Indian consumer. The brand did well if its product consistency was good; every time brand managers and accountants dropped quality or competition upped quality, the brand stuttered.

Farokh Engineer was an early cricketer to endorse brands. It is said that CK Nayudu, India’s first captain endorsed a brand in 1941. Engineer endorsed Brylcreem. Kapil Dev and Sunil Gavaskar were the next set, and the cricket World Cup win in 1983 was a watershed moment for cricketers endorsing brands as it coincided with the launch of colour television in India.

The Influencer Tsunami

All brands embraced image and brand authenticity, and consistency became suspect. Many marketers and Indian brand owners felt that image could overcome product flaws. That’s true in an era of shortages, never in an era of choice. Till the mid-’90s or late-’90s, this trend continued. In the ’90s, thanks to television and its reach, events and sponsorships became big. These were all designed to bring energy to the sponsor brand and event.

Everything so far was the physical era where physical presence mattered, and brand managers spent hours debating the right brand fit with a celebrity. Then came the digital era. And it was an influencer tsunami. Anyone with a few followers thought of monetisation and became an influencer. We saw more self-claimed experts and thought leaders in every field. The digital world pushes everyone and everything into a commodity and standing it is a challenge.

Here are a few data points on the influencer economy:

The global influencer market is valued at $32.5bn

More than 40% of brands globally spend at least a third of their marketing budget on influencers

India is the No. 1 country for Instagram with 362mn users

Half the brands use influencers. 38% of brands work with at least 10 influencers and 15% of brands work with 1,000 influencers. What happens to authenticity and consistency?

India has 4mn influencers earning on an average Rs 7,000 per annum. That’s peanuts

Every legacy brand has a challenge when appealing to the next generation. They also have a challenge of ageing celebrities and influencers.

Say Aye to AI

Enter the virtual influencer. I think we will see a lot of them in 2025. Virtual influencers are timeless, they don’t get into any faux paus, are fully controlled by the brands. This is a marketer’s dream.

We have Indian virtual influencers like Kyra with 2.6 lakh followers, Naina a 22-year-old Jhansi virtual influencer, Kavya Mehra a virtual mom influencer. Virtual influencers can have better engagement via creativity and storytelling. Every brand is in the process of creating its own virtual influencer and every physical celebrity is creating a virtual avatar.

Virtual influencers help target better, with better precision, quick scalability and address the right target audience. The challenge is always to humanise the virtual influencer.

What suffers is authenticity for me. We have too many snake-oil influencers out there. I also think that all influencers will come under some regulation now. Governments and industry advertising bodies will act to ensure consumer protection.

Let’s go back to A, C, E. Regulation will bring back authenticity and consistency for all influencers. Influencers—physical and virtual—are designed to drive brand energy, but at what long-term cost is something every brand manager needs to think about.

(The writer is ex-chairman, ASCI and an India Inc veteran with stints in PepsiCo and Aditya Birla group)