Growing up, Parth Jindal was surrounded by quiet reminders of the legacy he was born into. His mother would gently advise him to take interest in what his father does, “You’ll have to learn. You’ll have to do it at some point.” House staff would say, “See how your dad carries himself.” The message was clear: the legacy was his to carry.

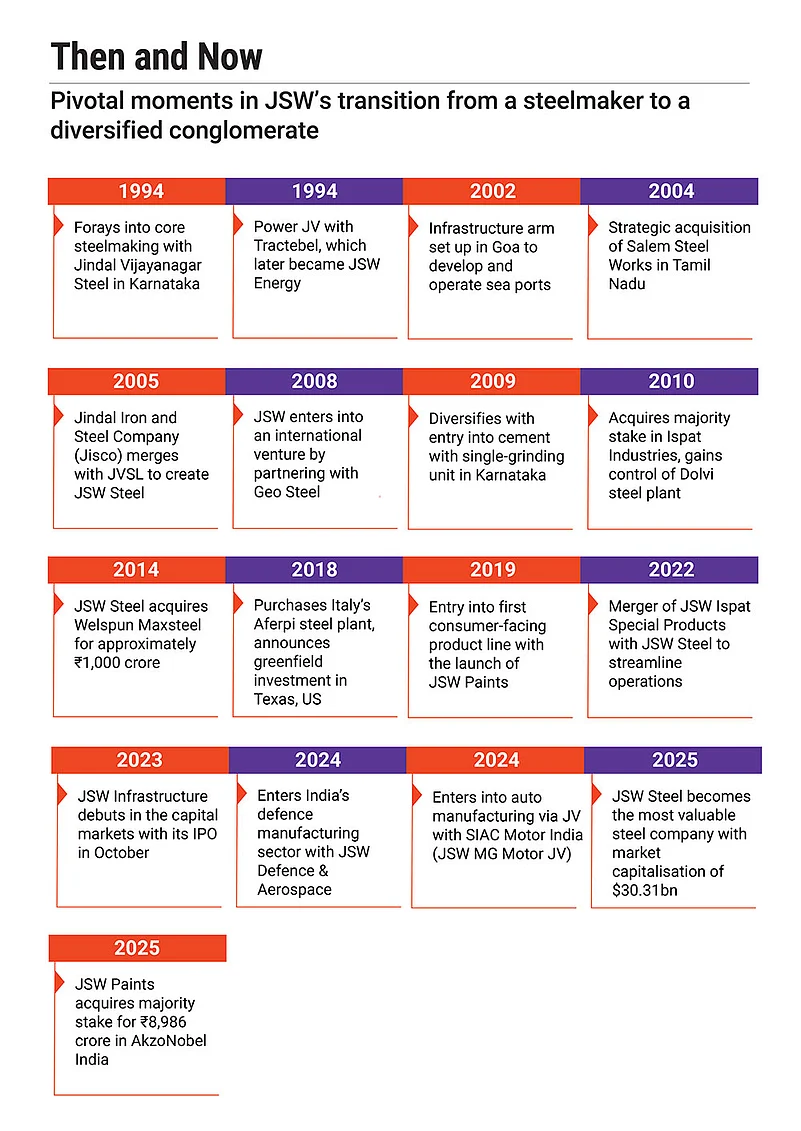

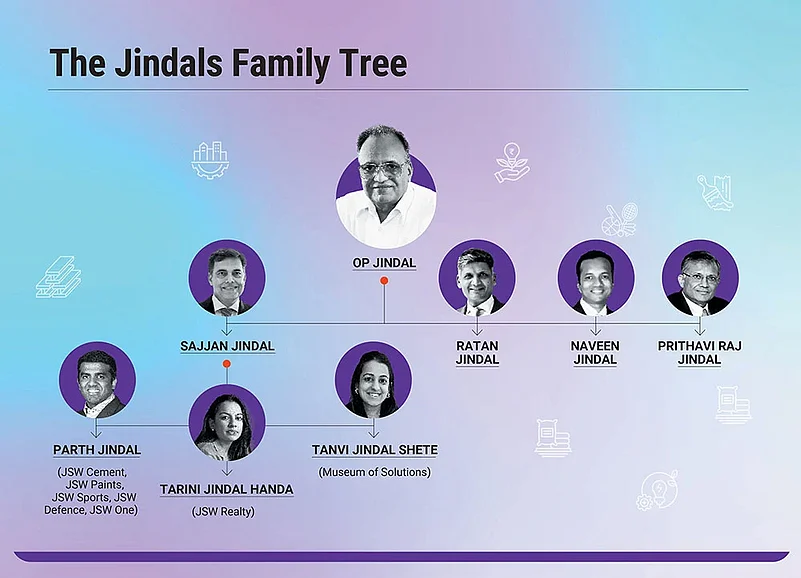

And what a legacy it is. Sajjan Jindal has built one of India’s most formidable industrial empires from the ground up. In the mid-1990s, as liberalisation began to reshape the economy, he built a steel plant in what was then a largely underdeveloped part of Karnataka.

That site, Vijayanagar, became the bedrock of what is now the over $25bn JSW Group, with interests spanning steel, energy and infrastructure.

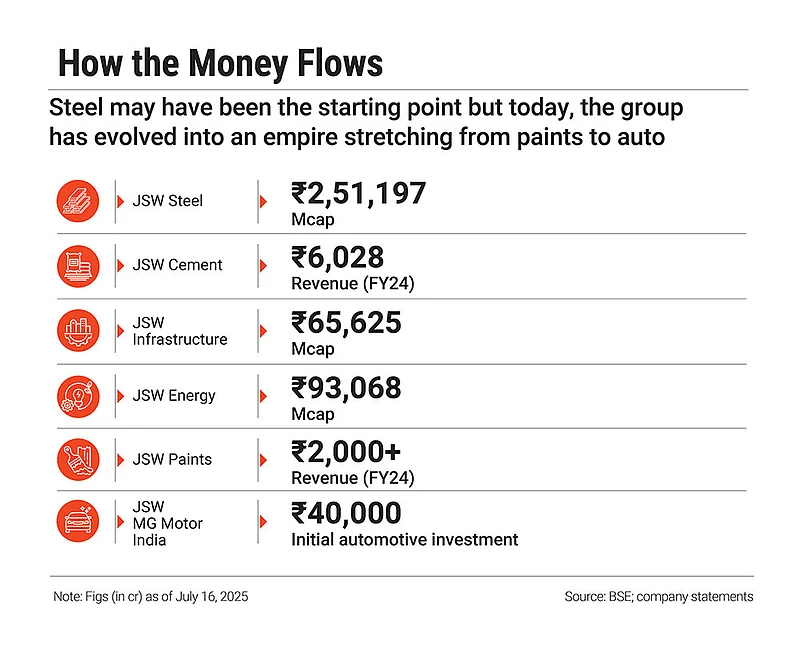

Today, JSW Steel is among the world’s most-valuable steel companies by market capitalisation. It has a capacity of over 35mn tonnes per annum (MTPA) with ambitions to scale to 50 MTPA by 2030–31. In 2024–25 alone, JSW Steel reported consolidated revenue of over ₹1.68 lakh crore and a net profit of ₹3,491 crore.

Early Start

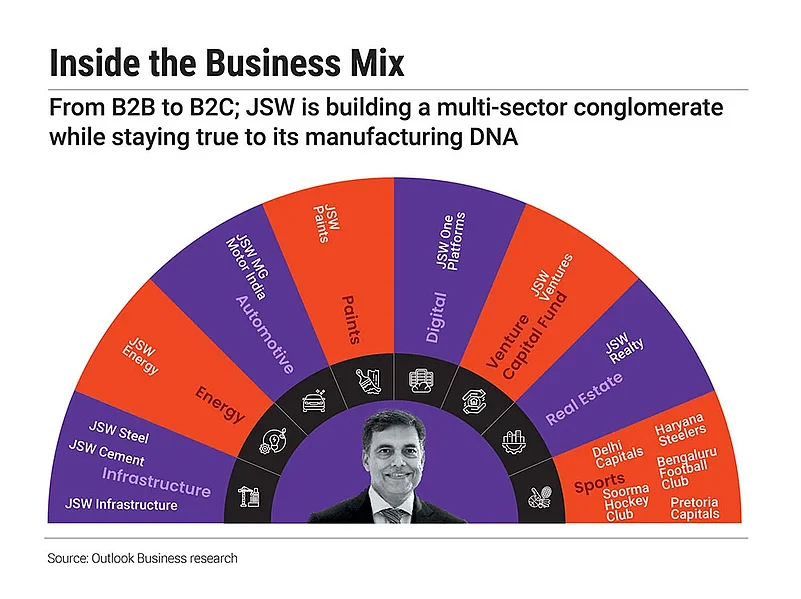

Now, Parth is stepping into those shoes. Ambitious, but pragmatic, he is taking on industry heavyweights in cement, paints, electric vehicles (EVs), defence, sports—sectors far from the group’s industrial DNA.

Parth’s early exposure to the business didn’t come from formal lessons. While his classmates headed to hill stations on weekends, his family’s ‘holiday home’ was something else entirely. “I think my parents did a very clever thing,” he says. Sajjan and Sangita Jindal built farmhouses inside JSW’s industrial complexes. “If we wanted a squash court or anything, it was always built in the factory premises,” Parth says.

Wearing a mini safety helmet with his name on it, Parth would tag along on evening drives to the factory. He would quietly observe his father speaking to colleagues, making plans and solving problems.

When he returned to India in 2016, after his MBA from Harvard Business School, the easiest path would have been to slip into a leadership role at JSW Steel or Energy. But stepping into the legacy wasn’t easy. Finding his own feet in the group took effort.

In meetings, he felt seen just as the owner’s son. “People were not sure how to react. There was definitely no respect,” he says. He took over JSW Cement, then a struggling arm of the group.

Around the same time, he forayed into JSW Paints, which wasn’t just about factories and volumes. It was about consumer behaviour, dealer relationships and brand equity.

Facing the Big Boys

Today, both cement and paints are growth engines in the group. But as Parth scales up, he finds himself going up against the giants of Indian industry. Cement pits him directly against Kumar Mangalam Birla’s UltraTech Cement and Gautam Adani’s Ambuja Cement and ACC; in EVs he is up against Tata Motors, Tesla, BYD, Hyundai and eventually Maruti Suzuki; and in paints, he’s challenging Asian Paints, Berger Paints and Birla Opus.

JSW Cement, which posted a profit of ₹62 crore in 2023–24 on revenues of ₹6,028 crore, has got markets regulator Sebi’s nod to raise ₹4,000 crore through an initial public offering (IPO). “I think the first marker of success in my head is that I have to take my company public. Hopefully, JSW Cement will go public soon. That would be a big milestone for me. Taking over a loss-making company, turning it profitable, and then, eight or nine years later, taking it public,” says Parth.

But it’s still up against mammoth rivals—UltraTech (over 150 MTPA capacity), Ambuja and ACC (over 170 MTPA combined), while JSW currently operates around 20 MTPA. To close that gap, it’s planning an aggressive expansion to reach 41 MTPA but that push comes with pressure.

Analysts say this creates supply dependence and capital intensity. The draft red herring prospectus clearly outlines that deleveraging hinges on IPO proceeds: “We intend to use a portion of the net proceeds...towards repayment...of certain outstanding borrowings.”

The company also remains exposed to volatility in coal, slag and freight costs, all of which have fluctuated significantly in recent years.

Meanwhile, JSW Paints recently acquired nearly 75% stake in Akzo Nobel India in a deal valued at about ₹9,000 crore, a move that positions it as a serious contender against market leaders. While it is a bold step, it is not without complexities. Analysts have pointed out that the decorative-paints segment continues to face headwinds due to increased competition, poor pricing power and a weak urban demand.

“The market’s reaction to the Akzo Nobel acquisition, which Parth championed, led to an uptick in JSW Steel shares,” says Vinit Bolinjkar, head of research at Ventura, a brokerage. “His blend of bold ambition with prudent management is perceived positively.”

High-Wattage Test

If cement and paints were Parth’s proving ground, the EV business may be his moon shot. JSW Group made its foray into the automobile sector in November 2023 via a joint venture (JV) with Chinese auto giant SAIC. JSW now holds a 35% stake in JSW MG Motor India, the JV. As part of its EV ambitions, the group has committed to a ₹40,000-crore investment for an EV and battery-manufacturing facility in Odisha and also plans to launch vehicles under its own brand name.

“I think our foray into auto is going to be the next JSW Steel for the group. It marries our group’s passion for manufacturing with my passion and interest in sales and marketing,” Parth says.

Being in the auto sector was always a dream of Sajjan Jindal’s. He toyed with the idea many times, but the high capital costs and deep technical complexity of internal combustion engines kept him out. EVs level the playing field. “Legacy auto players don’t have any real advantage when you go into EVs, because the technology is completely new and different,” says Parth.

Puneet Gupta, director, India and Asean automotive market at research firm S&P Global, says, “It’s definitely an ambitious plan but a realistic one. JSW has the scale, capital and ecosystem understanding to become a serious EV player.”

He goes on to add that their experience in raw materials and steel gives them manufacturing synergies and a strong base for backward integration. However, much will depend on how well they manage partnerships.

Parth points out that JSW has always relied on partnerships to bring cutting-edge global tech to India, be it JFE Steel from Japan or the AkzoNobel deal. The auto business is no different. Besides the JV with SAIC, JSW has also partnered with another Chinese giant, Chery, for the upcoming JSW-branded car.

“We’re very confident that Chinese technology and their know-how is the cheapest and best in the world. That’s why we’re partnering for technical know-how, while simultaneously focusing on deep localisation within India,” Parth says.

New Challenges

Yet the geopolitical terrain is tricky. “Yes, there are concerns due to ongoing geopolitical tensions. That’s why we are structuring all our deals as technology partnerships, where we receive only technical support from Chinese companies, while all manufacturing and localisation takes place in India under JSW,” he says.

Does Parth believe he can go up against the giants in these sectors? “Back in 1996, people must’ve asked my father the same question when he set out to compete with Tata Steel. And in two decades, not only did he catch up, he surpassed them,” he quips. JSW Steel has a bigger market capitalisation than Tata Steel.

Parth knows the business-to-consumer (B2C) world is a different beast. “You can’t replicate steel success in paints or cars. That’s why we’re building teams that understand those markets.”

Energy is a crowded space where JSW is pitted directly against RIL, Adani Green Energy and Tata Power, each with deep pockets and aggressive renewable ambitions

While Parth is building the group’s B2C ambitions, the JSW Group is also doubling down on its industrial backbone. JSW Group plans to invest about ₹5 lakh crore by 2030. Of that, nearly 80% is for steel and energy, highly capital-intensive sectors with long gestation periods.

Of this, nearly ₹2.5 lakh crore will be directed toward JSW Energy, where the group is scaling capacity from 12GW to 30GW. “For the first time in our group’s history, JSW Energy’s capex is going to be higher than JSW Steel’s,” says Parth, who now sits on the board of JSW Energy, signalling his deeper engagement in shaping the group’s renewable push.

Even in energy, the competition is fierce. It’s a crowded space where JSW is pitted directly against Reliance Industries, Adani Green Energy and Tata Power, each with deep pockets and aggressive renewable ambitions.

That kind of scale is familiar terrain for Sajjan Jindal, but less so for Parth, who admits he doesn’t think the same way. “He wanted me to become an engineer…Even now, if you ask him, he’ll say: ‘I wish he were an engineer. Engineers think differently’.” Parth is more drawn to strategy, consumer behaviour and branding, all skills better suited to JSW’s emerging bets.

Beyond Business

Earlier this year, the group announced its foray into the defence sector with the establishment of JSW Defence and Aerospace. The competition includes formidable players like Larsen & Toubro, Adani Defence and several legacy public sector undertakings.

“The diversification is a calculated move to drive sustainable value creation and de-risk the portfolio from cyclical heavy industries. Consumer segments like paints are designed to provide steady, high-margin cash flows. EVs aim to tap into a rapidly expanding market, and sports builds brand equity. This approach is strategic and value-accretive, not scattered,” says Bolinjkar of Ventura.

One such brand-building space is sports. JSW Sports is one of Parth’s earliest initiatives and now includes co-ownership of the IPL franchise Delhi Capitals, ownership of ISL’s Bengaluru FC and Pro Kabaddi’s Haryana Steelers, the Inspire Institute of Sport in Bellary and sponsorship of Olympic-level athletes in boxing, wrestling and athletics.

“Winning a gold [by Neeraj Chopra in javelin] for India at the Tokyo Olympics was my proudest moment,” he says. “That sense of national contribution matters deeply.” Sport also grounds him. “I love playing squash and football. I play football with friends every Sunday,” he says. It’s his way to reset from the demands of work.

In conversation, Parth is warm but direct. Ambitious, but also practical and open. A family man, he enjoys watching TV shows with wife Anushree and helping kids with homework. From his father, he is also learning not to bring the stress home. “It is easier said than done. But I am trying,” he says.