Not long ago, an analyst cornered Ambarish Kenghe, group chief executive at Angel One, India’s third-largest broker, with a discomforting question in a post-earnings meeting: “One of your peers has filed for an IPO [initial public offering]. Their revenue structure and their client base is higher than Angel’s, but the cost ratios are far lower. What are the reasons?”

It was no secret that the “peer” being referred to was Groww, the Satya Nadella-backed fintech that joined the race from nowhere in 2020 and became the market leader in no time.

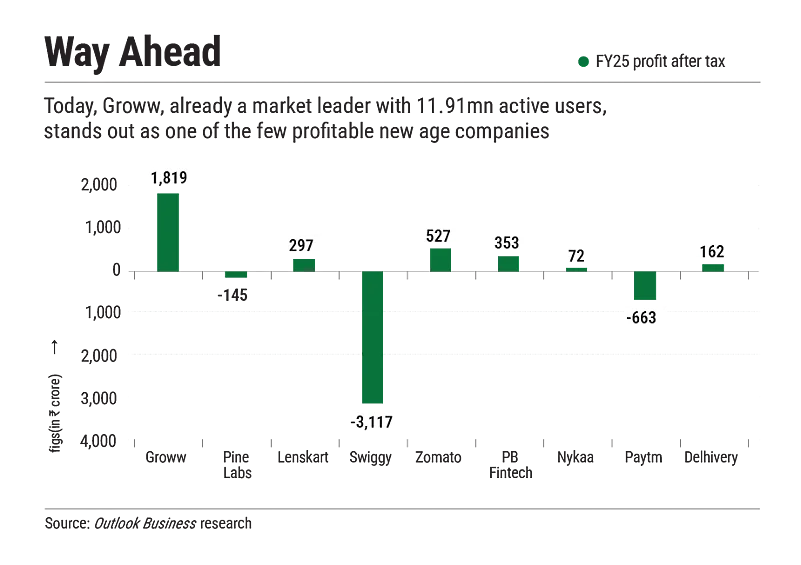

Also, it is now the most profitable of the two-dozen new age companies that have debuted in the public market since Zomato set the ball rolling in 2021.

“Groww’s path to the public market has been calm because of big profits in the rear view: from over ₹450 crore in 2022–23 to more than ₹1,800 crore in 2024–25,” says Ambareesh Baliga, a veteran equity analyst who advises family offices.

Of course, the online-broking business, which contributes about 80% of the company’s revenue, inherently has better unit economics, compared to new age sectors like food delivery or edtech. There are no physical goods or people involved in the transaction.

Moreover, as the analyst pointed out in the Angel One post-earnings call, Groww’s outperformance also holds true within the broking segment. Its profitability towers over larger rivals like Paytm Money, Upstox and IndMoney.

This wouldn’t be possible without a strong moat that’s deeply structural.

Getting Them Hooked

On a humid Kolkata evening in the summer of 2021, as his cab idled near Sealdah station, Shyam Negi scrolled through YouTube to kill time between rides. A video caught his attention, someone explaining how easy it was to buy shares using an app called Groww. “I thought, let’s give it a try,” he recalls with a shy smile. A few hours later, Negi made his first-ever stock investment.

That year India saw the creation of 35mn new demat accounts. Groww, which had started as a mutual-fund distributor in 2015 and began offering stock investments only in 2020, accounted for one in every five of those new accounts.

Its rapid uptake was no fluke.

Till that time most investment apps in India were not designed keeping in mind the general user who did just a few transactions a month. The priority for the platforms was the power user who bought and sold securities multiple times in a day. They contributed a lion’s share of the profits.

But Groww didn’t even enable features that traders needed to begin with. For its four co-founders, having spent a few years in Flipkart, the idea was to make buying mutual funds and stocks as intuitive as e-commerce.

For instance, the Groww app stokes the user’s curiosity with features like ‘most-bought stocks’ on a particular day or the ‘most-popular ETFs’. Meanwhile, its nearest rival Zerodha still doesn’t have such features.

Current and former employees that Outlook Business spoke with said that Lalit Keshre, the company’s co-founder and chief executive, spends hours every day studying the product. Product managers regularly interact with users across demographics, often through direct calls or Slack support tickets, to understand pain points firsthand.

“Designers at Groww had full creative ownership,” says a product manager. “If a flow took longer but offered a better user experience, it was still prioritised.” Development only began once the design was perfected, never the other way around.

Design always came before deadlines, says a source. Unlike most start-ups, designers work separately from product managers, intentionally, so that they are not under pressure.

“We never think of our product roadmap from a monetisation standpoint. We always think of it from a consumer perspective. We build a product only if there is a demand for it,” says Harsh Jain, co-founder and chief operating officer.

“Revenue is an outcome. If people stick with you for long and they use multiple products, you will make money,” he adds.

That strategy has clearly paid off. As of September 2025, Groww continued to lead India’s stockbroking market, commanding a 26.3% share in new demat users, while Zerodha was a distant second with a 15.6% share. The company also has a three-year average retention rate of nearly 78%, reflecting loyalty and high engagement among users.

The Content Machine

The first time Negi, the cab driver from Kolkata, came across Groww was during demonetisation. Amid the chaos, he searched online about the currency ban and landed on its blog post explaining the government’s move.

“We first started answering questions on Quora. At one point all four of us became top voices on finance on the platform. That’s when we started writing blogs,” says Jain.

“We didn’t use jargon or try to acquire users with our content by asking them to download Groww. We just tried to make finance easy to understand. We weren’t from the traditional finance industry. That helped us think about content from a consumer’s perspective,” he adds.

For this reason, Groww’s organic user acquisition has remained consistently above 80% over the past few years, reducing its marketing and promotional expenses. According to the company, it helped cut its cost of growth by almost half between 2022–23 and 2024–25.

Before 2020, most fintech companies which were mainly app based and didn’t treat web content as a serious growth channel. Groww did.

“In most fintech start-ups, SEO [search engine optimisation] rarely gets top priority. Leadership teams often chase short-term results through ads or influencer campaigns. SEO takes months, sometimes years, to pay off. Groww, from the time it was just a two- or three-year-old company, showed a lot of maturity by making a long-term bet on organic growth instead of chasing quick wins,” says Surdeep Singh, an SEO strategist who helps start-ups scale.

Initially, there were two approaches. Either companies would create short blogs or push all their content inside the app. The problem with that is Google doesn’t read app content. It only measures user behaviour inside the app (such as time spent).

Groww recognised that early. It built product-led SEO pages, templated pages on the web where users could perform most of the actions they did on the app.

For instance, the company used templated pages for thousands of stocks, a core feature of product-led SEO. So, users stayed longer on these web pages, which sent strong engagement signals to Google. When Google sees that users are spending time on a web page, it considers the site more valuable and ranks it higher.

The key difference between Groww and its closest rival, Zerodha, lay in their approach to SEO.

“While Zerodha built a strong web platform, it never truly optimised it for search the way Groww did. Groww, on the other hand, opened its platform to Google and created structured, scalable content that search engines could easily index, giving it a powerful organic growth advantage,” says Singh.

While Angel One and Zerodha are now ramping up their content efforts, Groww’s early investment in building a deep content library continues to give it a strong edge.

Zerodha, for its part, did launch Varsity, a financial-education platform. But it was built for learning, not user acquisition. “Varsity was designed for serious traders and self-learners, not beginners in Tier-II and Tier-III India who wanted quick, actionable insights,” says a fintech executive.

Options for the Future

Apps like Groww have unleashed a new generation of first-time investors, fuelling an unprecedented rush of domestic money into India’s capital markets. But this retail wave has also spilled into riskier corners such as futures and options (F&O) trading, where volumes have ballooned. Alarmed by the speculative frenzy, capital-markets regulator Securities and Exchange Board of India (Sebi) last year tightened F&O norms.

The move sent a shockwave through the broking sector. Zerodha said that its revenue might halve. While it reduced the growth of new users and topline for all major players, it seems to have hurt Groww the least.

According to analysts at Nuvama, a wealth-management platform, this is because Groww’s lion’s share of revenue comes from core stockbroking, while it is F&O for the rest of the big players. Moreover, even though the Sebi rules have dented its number of F&O customers, the volumes are still increasing due to the platform’s ability to drive up overall usage.

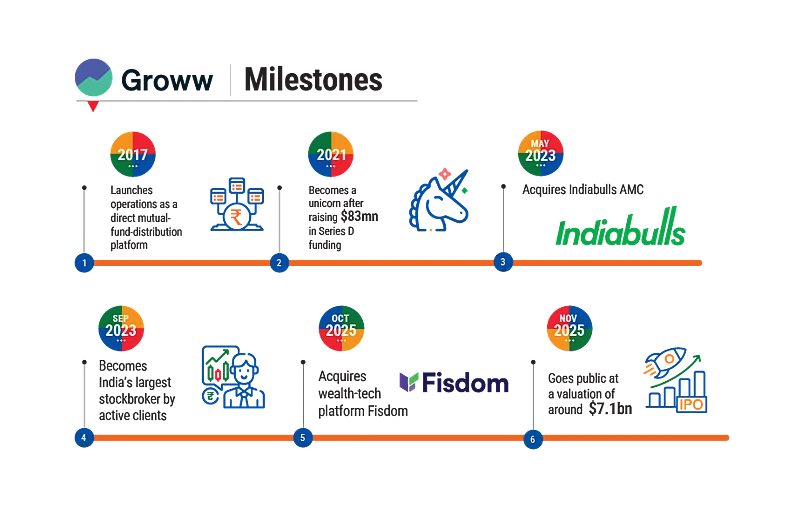

It is expanding beyond its brokerage roots into wealth management. Its 2023 purchase of Indiabulls Asset Management Company for about ₹180 crore gave it a mutual-fund licence. This year, it launched W, a wealth platform for affluent clients, and acquired a start-up called Fisdom to strengthen its advisory arm. It has also acquired a non-banking financial company licence and started disbursing credit.

“Fisdom also has a few physical branches,” Jain says with a chuckle, seemingly finding humour in the novelty of a brick-and-mortar shop.

To some quarters, the biggest risk of a publicly listed brokerage firm is the unpredictability of the stock market. The rationale is that if the market fares badly then new users don’t come in and the old ones desert the platform.

But Jain doesn’t think that is a major concern. He says that quarterly results are just snapshots. The company focusses on the long term.

“We see ourselves as a gateway to India’s capital market. Irrespective of what happens in a quarter or a year, India’s GDP will only rise. And more people will invest,” he says.

As the company’s appetite grows bigger, perhaps his rivals are the ones who need to worry.