It was the evening of November 26, 2008. Inside the plush Masala Kraft restaurant at Mumbai’s Taj Mahal Palace Hotel, Gautam Adani was having dinner with the then Dubai Ports chief executive Mohammed Sharaf. The two men, seated high above the city, were discussing trade and logistics when they heard the first bursts of gunfire.

From his vantage point, Adani could see the chaos unfold below with startling clarity. Within minutes, the Taj became a war zone. The two men, along with other guests at the restaurant, initially hid in the kitchen. Outside, Mumbai was slipping into a long, bloody night.

Adani survived. It wasn’t his first brush with violence. In the 1990s, he had been kidnapped at gunpoint in Ahmedabad and held for ransom.

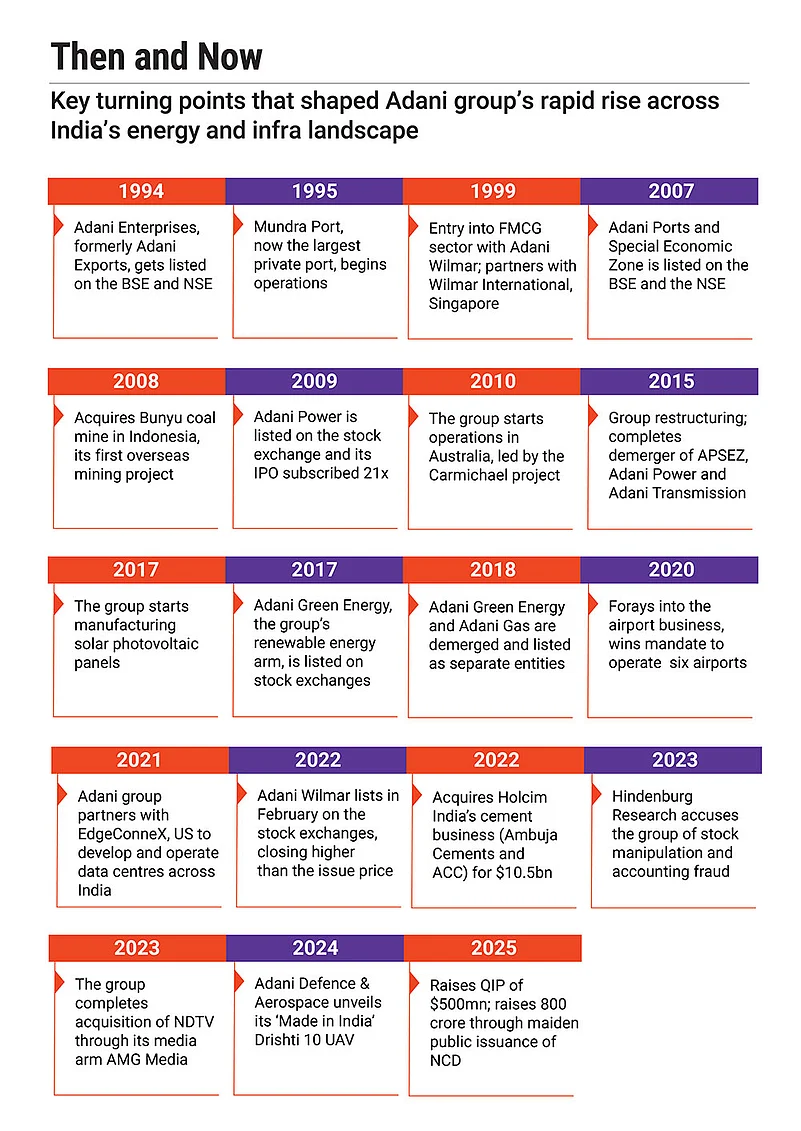

In 2023, the crisis would return—this time not through bullets, but balance sheets. A blistering report by Hindenburg Research accused his business empire of fraud and manipulation. What followed was a collapse in market value, wiping out $150bn at its lowest point. It was a moment of existential reckoning.

But Gautam Adani has always known how to survive storms.

Transfer of Power

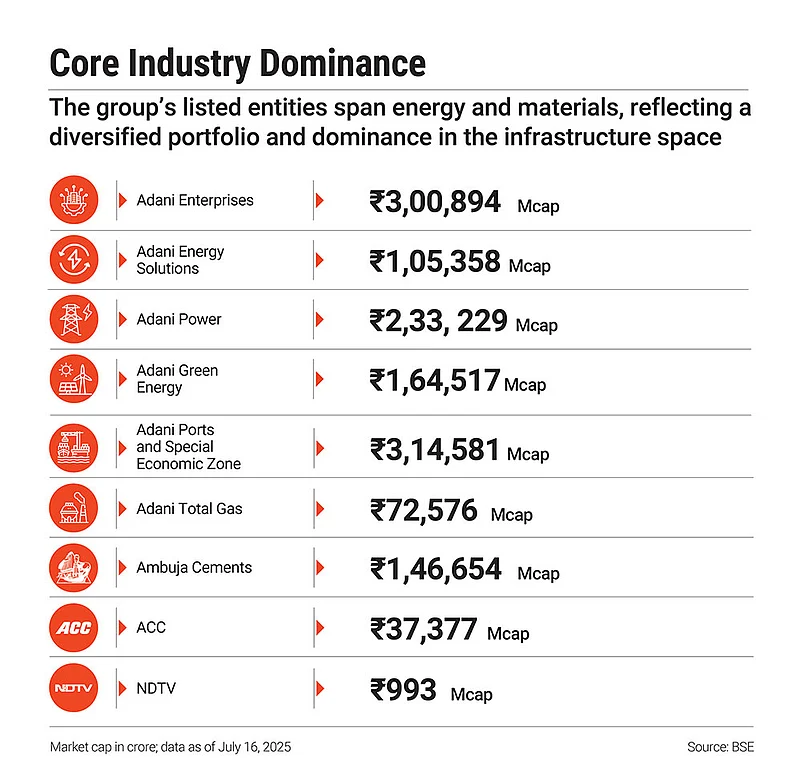

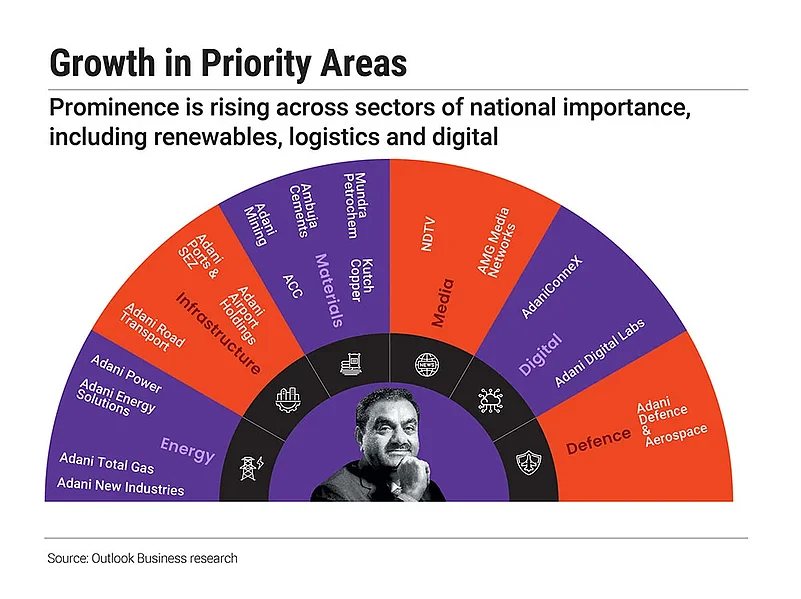

Now 63, the school dropout from Gujarat has built a $200bn empire that touches almost every part of India’s infrastructure: from ports and airports to renewables, data centres, cement and defence. His rise has been rapid and, to many, unsettling. But beneath the controversy lies a key alignment: each of his businesses is knitted tightly into India’s national aspirations—its hunger for energy, security, self-reliance and global relevance.

And as he begins to orchestrate a carefully calibrated transition of power to the next generation, a new question arises. Can a business shaped by one man’s ambition and scale be transitioned, not just seamlessly, but with resilience and trust?

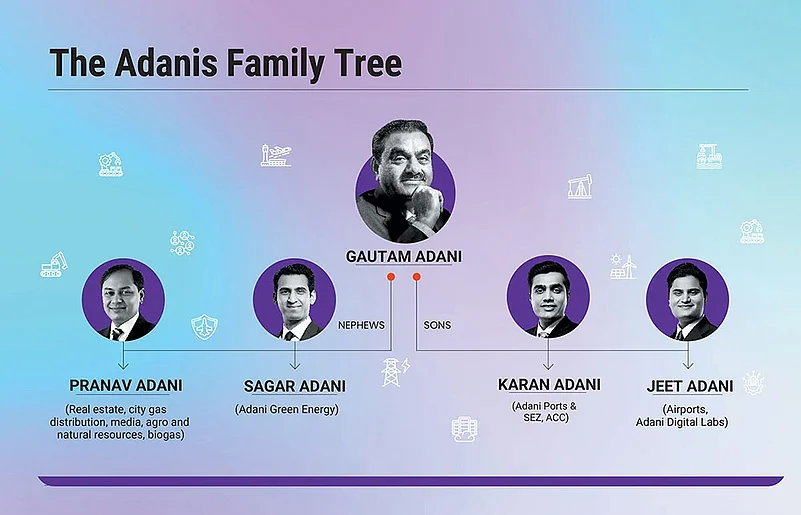

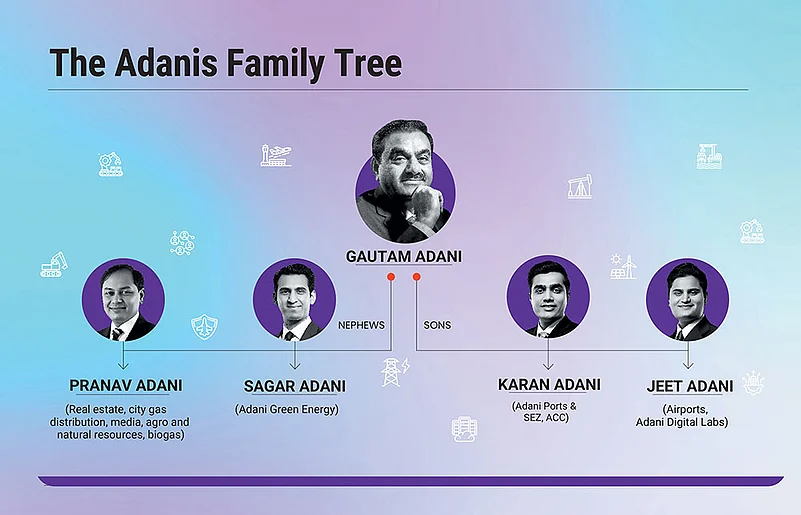

In an interview to Bloomberg in August 2024, Adani had said: “I am happy that all of them are hungry for growth,” referring to the four men he was preparing to entrust with the keys to the empire: sons Karan and Jeet, and nephews Pranav and Sagar. Each already leads a vertical. Each is being groomed for more.

Historically, India’s industrial legacies have followed a familiar script: divide the empire to preserve the peace. The Ambanis did it. So did the Birlas, and more recently, the Godrejs. Vertical splits have often been the currency of family harmony.

The Adani quartet chose differently.

Rather than carve up the empire, Adani’s two sons and two nephews opted for a model of shared control. According to Adani, the decision was theirs alone. On paper, it signalled unity. In practice, it marked the beginning of a quiet but significant shift within one of the world’s most closely held business conglomerates.

They are not the same. Pranav, the eldest, is fast, forward and aggressive, a man, colleagues say, “goes from first to sixth gear instantly”. Karan is reserved, private and often described as methodical. Sagar brings edge and clarity to the renewables push. Jeet, the youngest at 27, is loquacious, a digital native and perhaps the most distinctly modern of the four.

While they vary in leadership style and professional background, they remain unified by lineage, legacy and the singular challenge of stewarding a conglomerate under global scrutiny—one whose core sectors are uncannily aligned with India’s unfolding growth story.

Adani’s businesses are capital-hungry with long gestation periods. The group plans to spend $15–20bn in capex every year for the next five years. The returns will not come fast. Ports take time. Airports longer. Green hydrogen, perhaps decades.

What the Nation Wants

But each vertical also carries national significance.

Sagar’s renewables portfolio is key to India’s energy transition, helping meet net-zero commitments. Jeet’s push into defence technology mirrors the country’s ambition for indigenous military capabilities. And the data-centre business, developed under AdaniConneX, is quietly becoming one of the group’s most strategic bets.

As India enforces stronger data-localisation norms and gears up for a digital economy led by AI, fintech and 5G, control over data infrastructure is no longer a convenience but a national imperative.

Noting that India’s data infrastructure is reaching an inflection point, driven by surging AI workloads, 5G adoption and a decisive push towards data localisation, Sanchit Vir Gogia, chief executive and chief analyst, Greyhound Research, a technology-advisory firm, says that Adani’s multi-billion-dollar bet on data centres is more than an infrastructure play. It is a calculated move to capitalise on India’s emerging digital sovereignty stack.

“With its vertically integrated control over land, power and connectivity, Adani is not merely leasing capacity but is positioning as a digital landlord to both Indian enterprises and global hyperscalers,” he says.

Meanwhile, the ports network, from Mundra to Haifa, aligns with India’s maritime ambitions and geopolitical playbook, reinforcing New Delhi’s influence across the Indo-Pacific and into West Asia.

Adani Ports’ leverage ratio—2.6x net debt to earnings before interests, taxes, depreciation and amortisation (Ebitda)—is manageable but leaves little margin for error. Already, a post-Hindenburg bond issue had to be shelved. Credit-rating agencies such as Moody’s, Fitch and S&P have downgraded the outlook for several entities, citing governance concerns. The group has shored up capital through stake sale to investment firm GQG Partners and secured funding from Apollo Global Management, but global investor confidence remains uneasy.

The risk, some analysts believe, is of strategic overreach.

“Viewed from the outside, Adani’s strategy blurs the line between bold and overextended,” says Vinit Bolinjkar, head of research at Ventura, a brokerage. “It appears sequenced on paper, leveraging synergies, the sheer scale, capital intensity and overlapping timelines introduce real execution and financial risk.”

This puts significant pressure on the next generation. Each is tasked with executing a growth plan whose scale borders on audacious. Each must navigate an economic environment shaped as much by geopolitics as by market forces.

Faces of the Future

Pranav, with over 25 years in the group, leads its consumer-facing verticals and heads the politically delicate Dharavi Redevelopment Project in Mumbai. But controversy follows success. Sebi recently accused him of violating insider-trading norms, a charge he settled without admitting guilt.

Karan, the quiet force, leads Adani Ports and SEZ, as well as ACC Cement. Under his watch, port cargo market share grew from about 5% in 2009 to 27% today. He’s set a target of 1bn tonnes of annual cargo volumes by 2030.

Sagar is steering one of the group’s most-strategic projects in Khavda, Gujarat, where Adani Green is building what may become the world’s largest renewable energy park. The 538sq km facility will generate 30GW of clean energy. In 2024–25, Adani Green posted revenue of ₹9,495 crore, with Ebitda of ₹8,818 crore. Yet even here, storm clouds gather. Sagar has been named in a US Securities and Exchange Commission bribery case. The matter is ongoing.

Jeet, the youngest of the four, represents the group’s most visible generational shift. At 27, he leads Adani’s airport, digital and defence ventures—verticals at the intersection of infrastructure and national strategy. His portfolio includes the much-delayed ₹60,000-crore Navi Mumbai International Airport and a string of data and logistics projects positioned at the edge of India’s digital-sovereignty agenda.

Under his watch, Adani has also expanded steadily into defence manufacturing. The group now produces intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance drones (used in Operation Sindoor against Pakistan) small-calibre ammunition, naval missiles and anti-submarine warfare systems, while building up maintenance, repair and overhaul (MRO) capabilities through acquisitions like Air Works, India’s largest private MRO company.

Together, the Adani scions represent a pivot—from old-economy scale to new-economy ambition. But while their mandate is modern, the terrain is not.

Global Chessboard

The Adani group is not just a business, it is a barometer for Indian foreign policy. Under Karan’s leadership, the ports vertical has expanded into Sri Lanka, Vietnam and Israel—moves that align with India’s effort to counter China’s ‘string of pearls’ strategy. But geopolitics is fickle. In Myanmar, a military coup forced the group to exit a port project at a deep loss, selling out for $30mn after investing about $195mn.

The group’s alignment with the Indian state has been an advantage, and a liability. Its projects, from Dharavi to Haifa, often seem in sync with national priorities. But the very proximity that enabled its rise also invites allegations of cronyism. With elections, legal scrutiny and the investigations underway, any change in political weather could have material consequences.

“For Adani, business is all about efficiently managing through the difficult waters of geo-political turmoil,” says Sumeet Mehta, chief executive of Paradigm Advisers, which provides corporate finance and strategic advice to businesses.

Adani’s bets in critical infrastructure will help break the hegemony of the West, which makes the opportunities for the group almost limitless, he said, noting that past performance on in time execution of projects tilts the odds heavily in their favour, and raising capital should not be an issue.

Beneath all the strategy decks and earnings reports lies a more human question. Can the second generation lead with autonomy, or will they remain tethered to the founder’s image?

“The transition is a work in progress,” says Bolinjkar of Ventura. “The decision-making culture is still centralised around Gautam Adani. Decoupling the brand from the founder will take time.”

That time, however, may not be available in abundance. The world is moving faster. Trade wars, climate shocks, data nationalism and AI disruptions will test the group’s resilience in ways Adani never had to face. There is, as yet, no group-wide technology roadmap. The corporate structure—opaque, cross-held, complex—continues to trouble global investors. The final Sebi investigation looms. So does the question of leadership clarity.

For Karan, Jeet, Pranav and Sagar, the future is less a torch passed and more a fire contained. They are not just tasked with growing businesses. They must calm markets, answer regulators, placate critics and somehow, carry forward a story that refuses to sit still.