With climate action gaining momentum in India, a pack of clean-tech start-ups has taken off the blocks, their focus ranging from renewable energy to electric mobility. But to keep up with the global frontrunners in the sustainability race, these start-ups will need to find a way around a major stumbling block: capital.

And that’s no mean task, because, compared to fin-tech or deep-tech ventures, start-ups in the clean-tech space struggle to attract funds due to large capital costs, growth concerns, regulatory uncertainty and limited scalability.

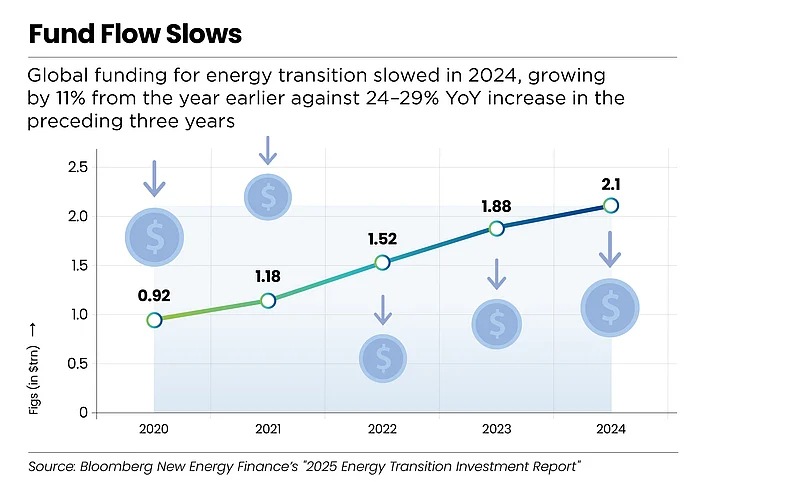

In 2024, energy transition attracted $2.1trn in funding globally, 11% higher than the previous year, according to Bloomberg New Energy Finance’s "2025 Energy Transition Investment Report". But this statistic hides a perturbing downtrend: the investment growth through the preceding three years was two-and-a-half times higher, ranging between 24% and 29%.

“Even this dwindling investment is flowing largely to established solutions, with China accounting for most of the growth. Meanwhile, the clean energy and the tech sector in the rest of the world is either stagnating or slowing,” says Pratyush Thakur, investment director and country head of Blueleaf Energy, a pan-Asia renewable energy platform that develops, finances and operates renewable energy and storage assets.

Out of Steam

Climate-tech companies raised a mere $50bn in private and public equity in 2024, a 40% decline from 2023. It was the third consecutive year of contraction for the sector. Further, out of over 800 operational climate-tech start-ups, only 25% have been able to secure venture-capital funds.

A recent study by IIMA Ventures and the Mitsubishi UFJ Financial Group points out that over the past decade clean-tech has garnered about $3.6bn in funding whereas fin-tech has attracted more than $19.3bn.

Srikanth Sola, founder of Bengaluru-based clean-tech company Devic Earth, believes that it is relatively easy to secure funds at the seed stage, but beyond this stage investors look for companies which generate good revenues and maintain top-notch quality in operations, management and products.

Sola’s start-up, for instance, has secured grants from both the Centre and the Karnataka government, which has helped in product development.

Although few ventures like Yulu, the electric bike-sharing service, and Bambrew, a sustainable packaging start-up, have made it to early-stage funding rounds, others have not been as fortunate. Less than 3% of start-ups go into the Series B funding stage or beyond.

Vaibhav Anant, founder of Bambrew, says, “While we have got early-stage investors like Blume Ventures and Blue Ashva Capital, there are very few investors who will invest in Series B and Series C, which require much larger cheques.”

Moreover, policy support for the sector has waned, with incentives such as feed-in tariffs and subsidies phased out and policies like carbon taxes not materialising. “Policy uncertainty in a fast-changing technology environment creates a challenging investment context, which is not helped by the fact that many climate-tech ventures are highly capital intensive,” says Thakur of Blueleaf Energy.

Investments, particularly in newly emerging sectors like clean tech need the comfort of consistent government policy, including predictability of subsidies and regulatory frameworks. Unfortunately, this is something funders can no longer bank on as demonstrated by the political upheaval in just the first few weeks of Donald Trump’s presidency.

Flustered Founders

Venture-capital funds remain hesitant to invest in clean-tech start-ups because of high risks and not-so-easy returns. Unlike software-driven start-ups which are capital-light, clean-tech solutions like renewable energy or energy storage need large investments. Thakur says, “Businesses in areas like carbon capture and transportation often require upwards of $25mn.”

Also, because many of these are not mature technologies, investors fear that they could easily be rendered obsolete by alternatives or shifting standards before they have scaled or generated decent returns.

In an ecosystem that depends crucially on valuations and scalability, the extended development cycles of capital intensive clean-tech projects can be a major dampener, especially when compounded by the risk of rapid technology obsolescence and policy flip-flops.

Clean-tech companies generally do not meet venture capital’s expectation of quick returns. “Typically, private funders run a seven-year fund, but sustainability-related start-ups require at least 10–15 years to show any sort of impact,” says Sathya Pramod, chief executive, Kayess Square, a Bengaluru-based firm specialising in mergers and acquisitions advisory and management consulting services.

Climate-tech start-ups like BlueSmart, Zypp Electric, Ola Electric and Euler Motors, offering electric vehicles (EVs) and battery-storage services, and those such as Devic Earth, AirOK and Varaha, addressing air pollution, have burst into the scene with no established playbook.

As a result, awareness about such businesses is limited among customers and investors alike. “There is a need for a lot of awareness in this space and a lot of patient capital,” says Anant of Bambrew.

Kishan Karunakaran, founder of biofuel marketer Buyofuel, says, “The understanding of even clean-tech-focused funds is limited. Their expectations from the sector tend to be unrealistic if not over-exuberant. With a number of funds still in the process of understanding the game, it will be a while before they become bullish.”

Bright Spots

Despite challenges, investor wariness is not uniform across the clean-tech sector. Certain areas such as energy-storage solutions seem more attractive to capital than others. Grid stabilisation has also emerged as a significant market opportunity due to the proliferation of renewable networks worldwide.

“The intermittency inherent to such networks has sparked substantial investments in various technologies from short-duration battery energy storage systems (BESS) to longer-duration pumped hydro,” says Thakur

India’s progress in the renewable energy space has stalled due to factors like the pursuit of self-sufficiency in green-energ-equipment manufacturing, leading to tariff and non-tariff barriers. These barriers have, in some cases, increased the cost of generation by at least 50% compared to initial forecasts, according to Thakur. Policy push and certainty, global collaboration and removal of trade barriers are some of the macro measures required to drive investment into the space, say experts.

Moreover, instruments like green bonds are yet to reach their full potential due to the absence of “greenium”—a premium on environmentally beneficial investments. Thakur believes that the long-term environmental risk reduction offered by clean-tech has, therefore, not been adequately incentivised.

But large corporations, driven by their net-zero commitments, have emerged as a significant source of funding for India’s clean-tech start-ups. “Corporations often have innovation arms, which seek new technologies to address pressing needs,” says Sola of Devic Earth. While corporate investments offer a promising stream of capital for the clean-tech sector, they need the air-cover of strengthened policy measures beyond EVs and clean energy.

Sola believes that more government-funded proof-of-concept studies would help the sector by exposing customers to clean-tech solutions and increase their credibility. For hardware-based clean-tech companies, product development licensing needs to improve.

Citing the example of China’s established ecosystem for product development, licensing and certification, Sola says, “In India, this is completely in the hands of private players which makes it quite expensive.”

Looking ahead, with the right policies in place, India can expect more clean-tech-focused investors to emerge. As the sector matures, so will the understanding of innovative technologies among investors, leading to realistic expectations regarding returns and scalability. As Pramod of Kayess Square says, “Adoption will take a while in India. We just need to wait it out a little bit.” The question is: does India have time on its side?