:The message from the government landed at around 4 pm one afternoon in early May—brief, firm and laced with urgency. The request was for a deployment of drones. Operation Sindoor was about to begin.

But even before the call came, the team at this defence-tech start-up was in action. “We were already in a trial run,” says its founder, who wished to remain unnamed. Their drones—built for night-time surveillance and designed to operate in GPS-denied zones—weren’t a reaction to the operation.

They were the result of months of preparation, built on groundwork laid as part of the company’s participation in the Innovation for Defence Excellence (iDEX) programme, a Ministry of Defence initiative that promotes innovation and supports start-ups building for strategic national needs.

The start-up had joined the programme nearly two years earlier. But instead of rushing to prototype, it spent almost a year refining the problem statement—part of an open challenge under iDEX. “User validation is much more important than telling the world you’ve built something,” says its founder. Over six months, the team worked closely with defence veterans—those who had lived experience of the problem—and created a 13-page problem statement addressing the challenge.

The programme offers two types of funding. However, once the first product is built, R&D is either left to the tenacity or capacity of the start-up—or it just stops

Once submitted, the solution went through multiple layers of government screening and filtering: compliance checks, quality-assurance benchmarks and standard validations. iDEX, the founder says, brought a discipline most start-ups never encounter. “We’re used to agility”, he says. “But iDEX taught us how to align speed with structure and rigour.”

That discipline, combined with constant mentorship and feedback, influenced core design choices. So, when the request came, the team didn’t begin work—they continued it.

Idex as an institution empower defence tech startup with financial support and industry exposure. The defence tech startups that are driving innovation, all intellectual property (IP) remains solely with the startup; IDEX does not claim any ownership or share in the IP.

Hits and Misses

Launched in April 2018, iDEX offers grants of up to ₹1.5 crore to start-ups and MSMEs working on cutting-edge technologies. The scheme has a budgetary support of ₹498.7 crore that runs from 2021–22 to 2025–26.

What sets the programme apart, however, is the structure that its system offers. A nodal officer from the armed forces who guides the entire process is assigned to a start-up. A partner incubator helps with testing, quality control and mentoring, say experts familiar with the process.

Beyond funding and market entry, the most significant help is the level of involvement from the end-user—a military-service unit—during development.

“For instance, we won a challenge to develop a foreign object debris detection system for a naval air station. We were given unlimited access to the operational runway, allowing us to get direct, constant feedback and mentorship to develop a product that perfectly suits their needs,” says Ashish Kumar Karir, a retired military officer and now head of land systems, Skylark Labs, a deep-tech company.

But dig deeper and concerns emerge.

Since many iDEX products are highly specialised and have limited dual-use potential, the absence of follow-up procurement can turn a promising innovation into a stranded asset, say founders.

To add to this, many start-ups either abandon the product midway or shut down entirely when they realise the economic model is unsustainable.

“We worked on a project with another start-up under iDEX, around 2018. The project was called ‘see-through armour’ for the Army. It’s been tested extensively, including at Army locations and ordnance factories,” says Sai Pattabiram, founder and managing director of Zuppa Geo Navigation Technologies, a drone-manufacturing company.

“It was launched in 2018, and to this day, there’s been no order. Now, with the rise of drone warfare, you have to ask whether that system is even relevant anymore,” says Pattabiram, adding that while iDEX is a good initiative, structural gaps require attention.

Then comes the issue of bureaucratic churn. Officers managing iDEX projects are frequently transferred, erasing institutional memory and resetting progress. A start-up founder says, “Yes, we had a similar experience with our Air Force project. Initially, things moved smoothly—we cleared two milestones. Then after the third milestone, there was no further engagement. The nodal officer who was driving the project was enthusiastic, but when he got transferred, the new officer just didn’t have the same level of interest.

Capital Gap

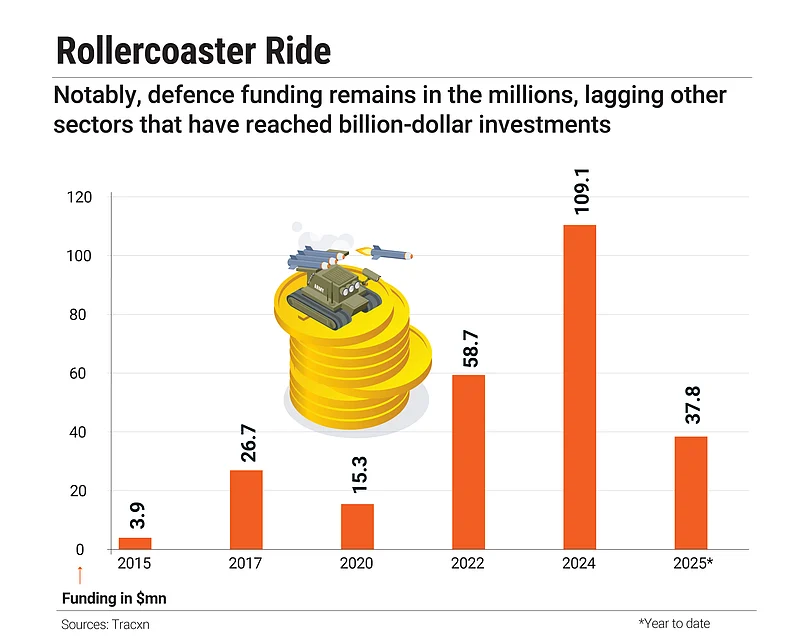

Funding for defence-tech start-ups has also lagged, with the highest investment being $109mn in 2024, shows data platform Tracxn.

The data shows a significant surge in funding starting 2017, reflecting increased investor confidence and a maturing start-up ecosystem. This trend continued through the pandemic, with notable growth between 2020 and 2024.

Anil Joshi, managing partner at venture-capital firm Unicorn India Ventures, says, “We typically see investments coming in only when there is a certain level of maturity in the product or technology for defence-tech start-ups. This creates a classic chicken-and-egg situation.”

Joshi adds that venture capitalists remain hesitant to invest unless there is a clear and viable business model in place. What can help, he points out, is a dedicated investment framework that supports long-gestation, high-potential ideas. Nurtured properly, some of these could eventually unlock billion-dollar opportunities.

Meanwhile, as private capital remains cautious, the government has stepped in to shoulder the responsibility of early-stage support.

“Currently, the funding limit in iDEX is ₹25 crore, which has already been increased from ₹10 crore. Institutions such as the Defence Research and Development Organisation also extend financial support to defence-tech start-ups through the Technology Development Fund. We are actively working to collaborate with banks and other institutions to further support these start-ups,” says Sanjeev Kumar, secretary, department of defence production.

On the issue of funding duration, he says, “There is no fixed time limit, as long as the start-up delivers on its committed outcomes.”

Half-Built and Halted

Recent progress notwithstanding, the ecosystem compares unfavourably when measured against more mature models like the US’ Defence Advanced Research Projects Agency (Darpa) or the tightly integrated frameworks of Israel and China. Darpa, the US Department of Defence’s innovation arm, is known for backing research that has led to breakthrough technologies such as the internet and stealth systems, through its fast-moving and flexible R&D model.

iDEX currently offers two types of funding: up to ₹1.5 crore for early-stage development and up to ₹25 crore for more advanced projects. However, each project is typically treated in isolation. Once the first product is built, the R&D is either left to the tenacity or capacity of the start-up—or it just stops.

This contrasts sharply with the “spiral development” approach used by Darpa, where successive grants—R1, R2, R3—are awarded as complexity increases, allowing start-ups to build deeper capabilities over time.

While iDEX mirrors some features of Darpa—soliciting innovations, developing prototypes and integrating them into services—the post-development procurement journey in India is far more painful.

“Darpa’s process is seamless. In India, even for a ₹8–10-crore order, start-ups are asked to provide a bank guarantee of the same value. It defeats the purpose,” says Ajai Chowdhry, cofounder of HCL, a global technology company. This hinders early-stage ventures, many of which lack the financial cushion. In contrast, Darpa not only funds development but shields start-ups from such liquidity burdens, accelerating commercialisation.

Escape Velocity

And yet, even in the midst of structural constraints, the programme is gradually reshaping the ecosystem.

Take the case of Agnit, a gallium nitride (GaN)-based semiconductor company. Historically, India lacked domestic capabilities in GaN, a semiconductor material for next-generation radars, jammers and electronic-warfare systems.

Agnit stepped into this void, but early traction was tough without a working prototype or market assurance. Through iDEX, the company secured a ₹1.5-crore grant, allowing it to cross the technology-validation stage. With a functional prototype in hand, investor conversations shifted. What once felt speculative became tangible.

“We wouldn’t have been able to get investor attention without that early-stage push,” says Harish Chandrasekar, chief executive and cofounder of Agnit. “Once you hit the prototype milestone, private capital starts to see the potential. But getting to that point is the hardest part, and that’s exactly where iDEX makes the difference.”

Chandrasekar adds that a sustained pipeline of support is critical because once a start-up reaches the prototype stage, it is far easier for the larger investment ecosystem—including venture capitalists—to step in. That early-stage viability-gap funding is crucial and the broader ecosystem needs to mature around this requirement.

As protectionism rises globally, India’s defence-tech start-ups are at a critical juncture. Experts emphasise that this moment demands stronger convergence and solution-oriented collaboration between institutions and the government.

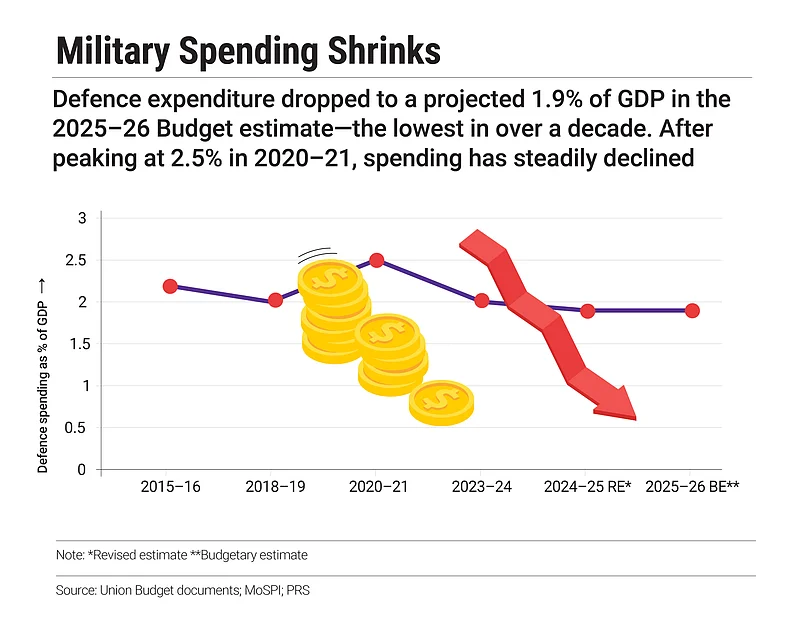

This challenge is particularly pressing given India’s geostrategic landscape, where the threat of a two-front conflict with Pakistan and China looms large. India’s ascent to the position of the world’s fourth-largest economy demands more than economic growth, it requires technological self-reliance and large-scale innovation.

The iDEX initiative is pivotal in driving this objective. However, its success depends on seamless collaboration between defence public sector undertakings, private enterprises, start-ups, academia and government entities. Steered wisely, India’s defence-tech ecosystem can thrive, meeting the country’s strategic needs and securing its future.

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Corrigendum -15th July 2025

This is with reference to the article titled ‘Can iDEX Create India's First Defence Tech Unicorn?’ published by Outlook Business on 30 June , which incorrectly states that the Innovations for Defence Excellence (iDEX) framework shares ownership of intellectual property (IP) developed by startups under the program.

We would like to clarify that iDEX does not claim ownership of the IP generated by startups during the course of product development under its schemes. As per the established policy, the IP rights remain entirely with the startups/innovators who create the technology. This approach is designed to strengthen startups, ensure ease of commercialisation, and foster an innovation-friendly ecosystem within the Indian defence sector.