Manoj Sharma pulled into a fuel station on Delhi’s Outer Ring Road at least a week before he should have needed to. On the way over, he had watched the needle on his eight-year-old WagonR sink with unusual speed. The attendant, leaning on the pump, confirmed it was dispensing E20 petrol, a 20% ethanol blend. “Is my car designed for this?” Manoj asked. The man shrugged. “This is what we have now.”

More than 800km away, in Indore, a gig delivery rider Santosh Patidar noticed a similar dip. Covering the same routes and carrying the same weight each day, his monthly fuel spend climbed from 24 litres to over 30 litres since his city’s pumps began dispensing E20.

In Karnataka’s cane-rich Bijapur district, sugarcane farmer Ramesh Goudar has reasons to view the transition differently: long-term ethanol supply contracts with a local distillery mean his cane fetches steady prices and on-time payments.

“The mills are paying faster than before and they take everything we grow,” he says. For Ramesh, who once had to chase delayed payments from jaggery makers or sell cane at distress prices to local traders, the ethanol-linked contracts have brought a rare sense of stability.

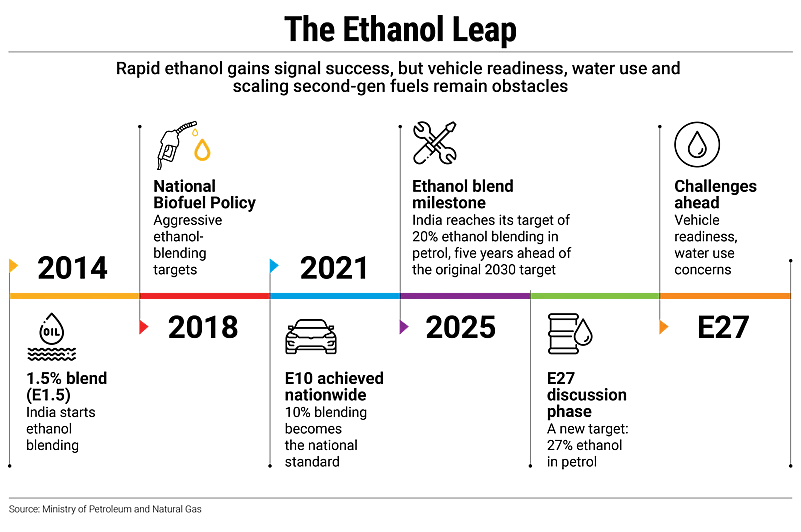

India has pushed through one of the most aggressive ethanol-blending programmes in the world, hitting an average blend rate of 20% in 2025, five years ahead of its original target. The Ministry of Petroleum and Natural Gas touts it as a triumph of energy security, rural upliftment and environmental stewardship.

Now, it is considering raising the bar to 27% (E27). The achievement is held up as a model for other developing nations. In September, the Supreme Court declined to entertain a public interest litigation that challenged the rollout of 20% ethanol-blended petrol.

Beneath the celebratory rhetoric, however, lies a more complicated ledger: one of winners and losers, shifting agricultural patterns and a fleet of vehicles that may not be ready for what is coming.

The Policy Push

India’s ethanol story is not new. In 2014, ethanol accounted for just 1.5% of the petrol sold in the country. By 2025, that figure had jumped nearly 13-fold, thanks to procurement mandates, financial incentives and infrastructure upgrades.

The official narrative is glowing. “India has saved approximately ₹1.36 lakh crore in foreign exchange by reducing crude oil imports,” petroleum minister Hardeep Singh Puri declared in May. “At the same time, ₹1.96 lakh crore has been paid to distilleries, fuelling the growth of the domestic biofuel industry, ₹1.18 lakh crore has gone to farmers, boosting rural incomes.”

Most of India’s 25 crore petrol vehicles were not designed for high ethanol blends. The bulk of pre-2023 models, especially 14 crore two-wheelers, are built for E10

The environmental claims are similarly bold. The ministry says ethanol blending has cut carbon-dioxide emissions by 698 lakh tonnes since 2014 and reduced particulate-matter emissions in urban areas. E27, officials say, will deepen these gains.

Yet this headline figure of “20% achieved” conceals a more fragmented reality. Actual blending varies by region, depending on feedstock availability, blending infrastructure and seasonal supply fluctuations.

Whether E27 is a concrete roadmap or an aspirational target remains unclear. The trouble is that most of India’s 25 crore petrol vehicles were not designed for high ethanol blends. According to the Society of Indian Automobile Manufacturers (Siam), the bulk of pre-2023 models, especially the country’s 14 crore two-wheelers, are built for E10. At E27, many risk reduced mileage, increased wear and cold-start problems unless their hardware and engine control units are recalibrated.

Engineers at the Automotive Research Association of India also note that ethanol is more corrosive than petrol and its higher oxygen content affects combustion dynamics. “If the engine or its design is not upgraded to suit the ethanol blend, it will definitely have an impact,” says Ayush Lohia, chief executive of Zuperia Auto, an electric-automobile manufacturer.

Moving from E10 to E20 was already significant; E27 adds complexity and cost.

In Madhya Pradesh’s Jabalpur, ride-hailing driver Ramesh Kumar Yadav says his 2018 sedan’s fuel injectors had to be replaced twice in the past year, each repair costing over ₹12,000. “Earlier, this happened maybe once in three or four years,” he says. “Now the service centre says it’s because of the new petrol.”

For manufacturers, the price tag is clear. A Niti Aayog roadmap estimates that flex-fuel compliant four-wheelers cost ₹17,000–25,000 more than standard petrol models, while two-wheelers cost an additional ₹5,000–12,000. For India’s price-sensitive mass market, that is not trivial.

“From the perspective of vehicle owners, there will be some impact. The auto industry will have to adopt these changes and some of those costs may eventually be passed on to customers to ensure engine components are capable of handling the new blend,” says Lohia.

Winners and Losers

The sugar industry is the undisputed champion of India’s ethanol policy. Mills and distilleries, especially in Uttar Pradesh, Maharashtra and Karnataka, have secured long-term demand for their output. Distilleries have expanded capacity, often with concessional loans and soft credit.

Ethanol procurement prices, currently around ₹65–70 per litre for cane-juice ethanol, provide predictable returns. Some mill owners treat ethanol production as a more reliable revenue stream than sugar itself, allowing them to hedge against international sugar prices.

Second-generation ethanol from crop residues, municipal solid waste or non-food feedstock is at pilot scale, far from displacing cane-based supply

Oil marketing companies (OMCs) such as Indian Oil, Bharat Petroleum and Hindustan Petroleum save on crude imports and post record dividends: government receipts from central public-sector enterprises jumped to ₹74,016 crore in 2024–25 from ₹39,558 crore in 2020–21, with OMCs a major contributor.

A significant share of these profits, economists note, stems from the fact that ethanol’s lower procurement cost is not proportionately reflected at the pump. In effect, the price difference that could have eased consumer costs has been absorbed into OMC margins.

For vehicle owners, the picture is mixed. Older cars and two-wheelers may need retrofits or face higher maintenance bills. In mileage terms, ethanol contains less energy per litre than petrol, meaning more frequent refuelling even without mechanical inefficiencies. For high-mileage commercial riders, such as delivery agents and taxi operators, this could cut margins.

The pump price offers no relief. Ethanol is cheaper than petrol at the procurement stage, but once central excise, state value-added tax, dealer commissions and OMC marketing margins are added, the consumer sees no difference at the forecourt.

In a response to queries regarding concerns on ethanol blending in petrol, the petroleum ministry said that despite the goal of using ethanol to lower fuel costs, ethanol prices haven’t decreased, and in some cases, have even risen above petrol prices.

“This is primarily due to increased procurement costs for ethanol, including transportation and GST [goods and services tax], which have outpaced the initial cost advantages seen when ethanol was cheaper than petrol.”

Water, Land and Food Pressures

India’s ethanol production is still dominated by first-generation biofuels from sugarcane and maize. Sugarcane is grown largely in Uttar Pradesh, Maharashtra and Karnataka, with a water footprint exceeding 2,000 litres per kilo of sugar.

In water-stressed districts, this creates a perverse allocation problem: scarce groundwater is used to grow a fuel crop rather than food.

Agricultural economists warn that diverting cane and maize to ethanol risks raising food prices and exacerbating local shortages. “What we’re really dealing with here is a food–water–land nexus,” says Abhishek Saxena, former public policy expert at Niti Aayog, a government think tank. Second-generation ethanol from crop residues, municipal solid waste or non-food feedstock remains at pilot scale, far from displacing cane-based supply.

In drought-hit parts of Marathwada, local activists report borewells running dry weeks before the monsoon, even as cane fields remain lush. “We’re pumping our future into ethanol,” says Latur-based farmer advocate Shrikant Deshmukh. “It’s like filling a swimming pool while the village queue waits at the hand pump.”

For E27 to amount to more than an achievement on paper, ambition must be matched by realism. That means accelerating the shift to second-generation ethanol made from crop residue and waste, so that food and water resources are not sacrificed at the altar of energy security.

It means phasing in strict hardware-compliance rules for all new vehicles, rather than leaving motorists to discover at the pump that their machines are unfit for the blend. And it means reworking the pricing architecture so that ethanol’s lower cost is visible in what consumers pay, not buried under layers of tax and marketing margins.

The challenge is ensuring these measures are in place before consumers conclude that the green-fuel experiment is just a one-sided bargain.

As India pushes ahead with E27, the policy is more than a change in fuel composition. It is a test of whether the country can match its climate ambitions with the realities of a sprawling and diverse vehicle market.

Meeting the target will demand cleaner fuel, sharper regulation, technological upgrades and a careful balance between economic and environmental priorities. The way India manages this transition will influence not only its energy future but also the credibility of its climate commitments.