If a man can make cars, why not a woman?” asks 23-year-old Dhanashree Dipak Murbade, a team leader in the assembly line at the Tata Motors passenger vehicle plant in Pimpri-Chinchwad, Maharashtra.

Murbade and her group of women are the ones responsible for the steady flow of Tata Harriers and Tata Safaris that roll out of the factory gates. Difficult to believe but yes, these are the women who keep the sports utility vehicles’ (SUVs’) wheels running.

Indian shop floors have seen a radical change over the past few years. Thanks to growing automation, the presence of women in production-related activities, which were earlier male dominated, has seen a steady rise.

Women Welcome

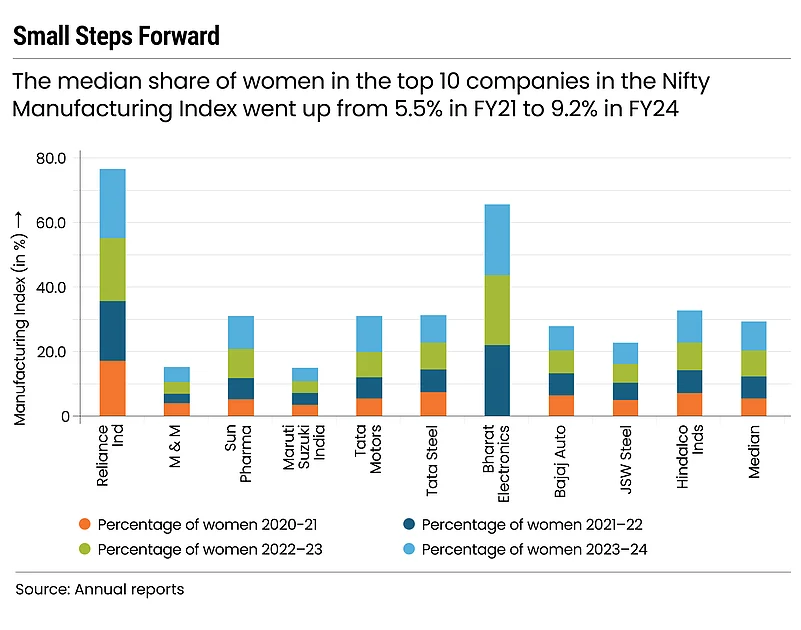

The top-10 companies in the Nifty India Manufacturing Index have seen more women joining the workforce. The median of percentage of women in their staff has shot up from 5.5% in 2020–21 to 9.2% in 2023–24.

Take the example of Tata Motors. The company has seen an increase in participation of women from 5.5% in 2020–21 to 11.1% in 2023–24. Outlook Business found that the trend of growth in the share of women workers was consistent across the top 10 companies in the Nifty India Manufacturing Index.

"We are also aggressively inducting women in our commercial space, which involves a lot of travel to the field. But now it has become a norm. Nobody asks, ‘Can we hire them?’ or ‘Can they do it?’ Every year, for the past three years, over 25% of our new hires on the shop floor have been women,” says Sitaram Kandi, chief human resources officer, Tata Motors.

There are a slew of companies that have opened their factory gates to women workers. Last year Vedanta, under its Project Shree Shakti, launched women-exclusive night shifts at its smelter operations in Jharsuguda, Odisha. To increase employment of women, Ashok Leyland, known for manufacturing trucks, has set up an all-women assembly line with 80 women employees at their Hosur plant in Tamil Nadu.

At its Halol facility in Gujarat, MG Motor India produced its 50,000th Hector, assembled entirely by an all-women team. Since its launch, the company claims to have collaborated with local panchayats to encourage more young women to join the workforce.

Companies are prioritising both infrastructure improvements and tweaking policy to attract more women to the factory floor.

Tweaking the System

Traditionally, manufacturing lines were designed for the average male worker, in terms of height, weight and physical reach. When women were inducted, challenges emerged in reaching certain workstations or handling heavier components.

“Instead of reallocating these tasks to men, we took it as a challenge and made engineering adjustments. We introduced ergonomic improvements such as adjusting workstation heights, adding hydraulic lifts and manipulators, and optimising tools to ensure that anyone—regardless of gender—could perform the tasks efficiently,” says Kandi.

Ergonomics focuses on designing workspaces, tools and processes to fit the people using them—reducing strain, preventing injuries and enhancing efficiency.

“If a woman is working on the line, we make sure it is ergonomically designed to prevent injuries and strain. For example, some of our devices use very tiny screws that need to be picked up with a screwdriver nozzle,” says Josh Foulger, president of Zetwerk Electronics, a manufacturer of consumer goods.

To assist with this, the company uses a jig that helps separate the screws, making them easier to pick up. Another jig holds the product in place, allowing for smooth and precise screwing.

Experts say that with automation taking care of the heavy lifting and repetitive work, women can focus on fine-tuning machine operations, optimising production and improving efficiency. The training process is also shorter, making it easier for women to learn and excel in these roles.

“We now have several women operating CNC [computer numerical control] machines which are used for cutting, shaping and assembling materials with high precision. As a result, women are more confident and interested in roles that were traditionally seen as male dominated,” says Kaushik Mudda, chief executive, Ethereal Machines, a start-up that provides precision manufacturing for high-tech clients in sectors like aviation and health care.

Even though it sounds stereotypical, industry insiders say women’s sincerity and nimble fingers are also something that helps them in manufacturing. Nimble fingers can help women in manufacturing in several ways, especially in industries that require precision, dexterity and attention to detail.

“Women working in factories handle assembly jobs, where their focus and nimble fingers make a significant impact. These skills are highly valued globally,” says Atul Lall, vice-chairman and managing director, Dixon Technologies, manufacturer of consumer durables such as televisions, washing machines and smartphones.

The company’s Tirupati campus has nearly 48% women. Lall claims to have observed that the productivity levels, commitment and diligence among women employees are exceptional, which contributes positively to the overall output.

The ESG Factor

Today, in India, women are proving their adaptability and efficiency in high-tech manufacturing, prompting companies to invest in training programmes to harness their potential. Tata Motors' Kandi says that since no experienced female talent was available in the market, they had to train freshers from scratch. Within three months, they matched the productivity and quality standards of the company’s regular lines. Their learning ability and desire to excel have been exceptional, adds Kandi.

Recruiters have also highlighted that factors like stability, discipline, lower absenteeism and higher productivity contribute to the preference for women in these roles.

Another reason that makes corporations hire more women is part of the diversity hiring initiative that is followed by most companies. With the aim to boost their environmental, social and governance (ESG) scores, companies are focusing on hiring more women. A 2024 report by job portal Foundit, indicates that diversity hiring in India has grown by 33% year-on-year. Having a good ESG score helps companies in various ways including attracting investors and improving financial performance.

According to a study by professional-services firm, Deloitte, companies with a 10-point higher ESG score (compared to another company) have, on average, a 1.2x higher enterprise value/earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation and amortisation (EV/Ebitda) multiple, which means investors are willing to pay more for the company relative to its earnings.

“Many impact funds prioritise gender diversity and women’s empowerment when assessing potential investments. Sustainability and reporting frameworks also consider these factors, requiring disclosures on women in leadership. Investors analyse these trends over multiple years rather than a single data point, ensuring companies demonstrate long-term commitment to gender diversity,” says Ambalika Gupta, head of sustainability at Snowkap, a software as a service platform.

The annual reports of the companies also indicate that companies are focusing on gender sensitive policies such as, providing maternity leaves to women, facilitating educational and skill development opportunities and eliminating hiring biases. For instance, Mahindra & Mahindra has introduced the 'Hire Right' programme to eliminate hiring biases and incentivise female referrals.

And Now the Hurdles

But big challenges remain. First is different labour laws in different states. Several states such as Uttar Pradesh, Karnataka and Maharashtra amended laws to make women work in factories. However, many other states including Bihar, Rajasthan and Kerala prohibit women from working in night shifts. This in turn becomes difficult for the industry to hire more women.

Housing women workers is another hurdle. Without dormitories or hostels companies are forced to hire from a limited local talent pool. India’s notorious public transport system is yet another problem.

Companies are loath to hire women because judicial precedents and government policies ask employers to provide safety measures such as transport.

In 2000, the Madras High Court ruled that women are allowed to work night shifts, if employers ensured their safety. The court said, “Instead of restricting their right to work, it is the duty of the employer to ensure their safety by providing adequate safeguards, including transportation and security measures."

Dixon’s Lall says, “Night shift-policies require women to be dropped home, which is challenging if you have a large workforce. Instead, we are advocating for solutions like secure bus services with designated pickup points.”

The Make in India initiative was launched in 2014 with the intent to make the country a global manufacturing hub by 2030. At a time when many countries are diversifying their supply chains and reducing dependence on China, this becomes an important opportunity for India to emerge as a significant player in manufacturing.

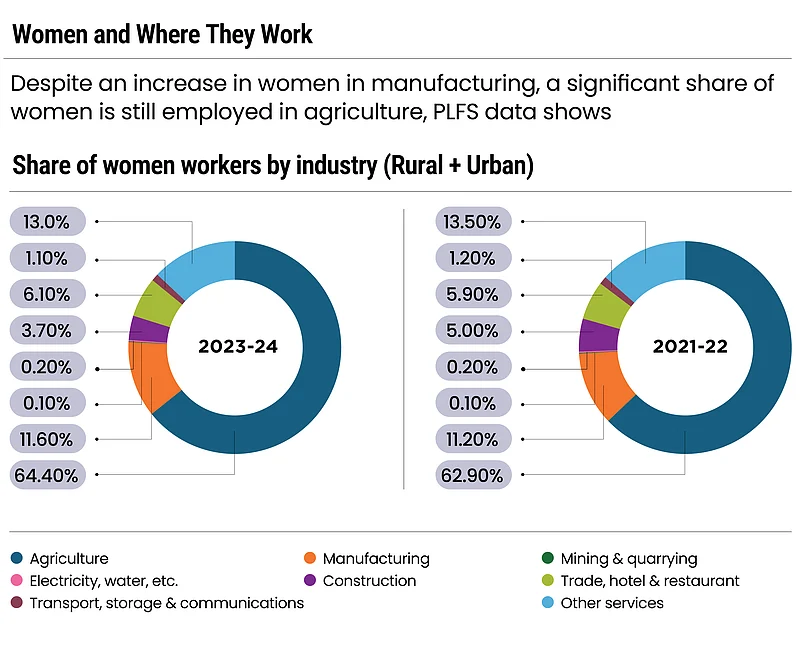

The manufacturing sector contributes to around 16–17% of India's GDP. For the country to improve its position in manufacturing, the World Bank indicates that the country’s manufacturing output can increase by 9% if more women join the workforce.

Will India follow in the footsteps of the Four Asian Tigers—Hong Kong, Singapore, South Korea and Taiwan—whose phenomenal rise was in part due to the inclusion of female labour in industries from the 1950s to 1990s?

Or will it keep its factory gates closed to women workers and limp towards Viksit Bharat?