When Manasi Tata was asked to step into her father’s shoes at Toyota Kirloskar Motor (TKM), it wasn’t after years of shadowing him or via a formal succession planning. It came in the middle of grief. In the space of just one day, her world turned upside down. After the sudden passing away of her father Vikram Kirloskar in November 2022, Manasi was handed a role she hadn’t expected to take on so soon.

“Within 24 hours, everything changed, and I was given this position for which honestly, I wasn’t sure if I was prepared,” she recalls. Pregnant with her second child, she stepped into a role that had seemed far away, until it wasn’t.

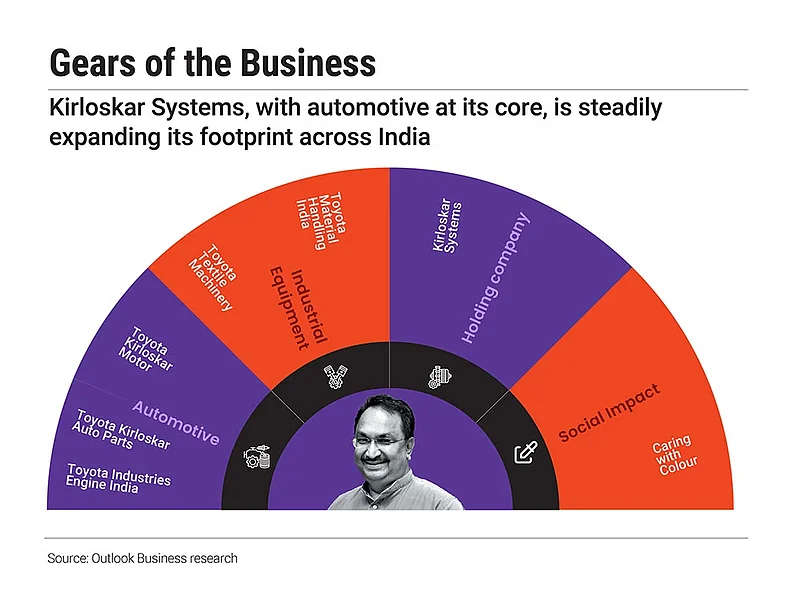

Following Vikram Kirloskar’s death, his wife Geetanjali Kirloskar took over as chairperson and managing director of Kirloskar Systems, which is Toyota’s joint-venture partner in India. While Manasi leads TKM as its vice-chairperson, Geetanjali currently drives new partnerships and represents the group on key platforms.

Bridging Two Worlds

Vikram Kirloskar wasn’t one for long lectures. “He wasn’t an over-communicator,” Manasi says. “He would tell me certain things, and then we’d be talking about music.” At the time, those conversations had felt casual. “I thought, ‘Oh, I’ll never really have to think about these things. Dad is going to be around forever’.”

But when the time came, everything he’d ever said came rushing back. Those handful of principles became her compass. “I follow those few golden rules to the tee,” says Manasi, who is married to Neville Tata, son of Tata Trust chairman Noel Tata.

She didn’t arrive at TKM with an engineering degree. She has a Bachelor of Fine Arts degree from the Rhode Island School of Design, US.

For Manasi the challenge will be how she can deepen the partnership with Toyota. They need to adapt to India’s shifting automotive landscape

Manasi trained on the TKM shop floor as a technician, going through the same exercises as other factory workers. “The factory is the heart of the company,” she says. “I feel privileged to have gone through all of that training to truly understand what it means to build a car.”

In her personal life too, Manasi has found herself drawing on both worlds, the painter’s mind and the corporate discipline. “A very technical world on one end of the spectrum, and a very creative world at the opposite end. And both of these have helped me so much in my personal life,” she says. From tightly scheduled mealtimes and naps to encouraging free-flowing creativity, she consciously uses both ways of thinking to raise her children.

Still, when she took over her father’s position at TKM, she carried doubt. “Some of the challenges come from being conscious of the fact that I’m not an engineer,” she says. Her father was. “He built the factory. He knew it inside out…He designed products himself. And I was always very self-conscious, less about being a woman, and more about being a painter. I used to wonder, ‘Am I really going to be able to contribute to this company’,” she says.

Switching Gears

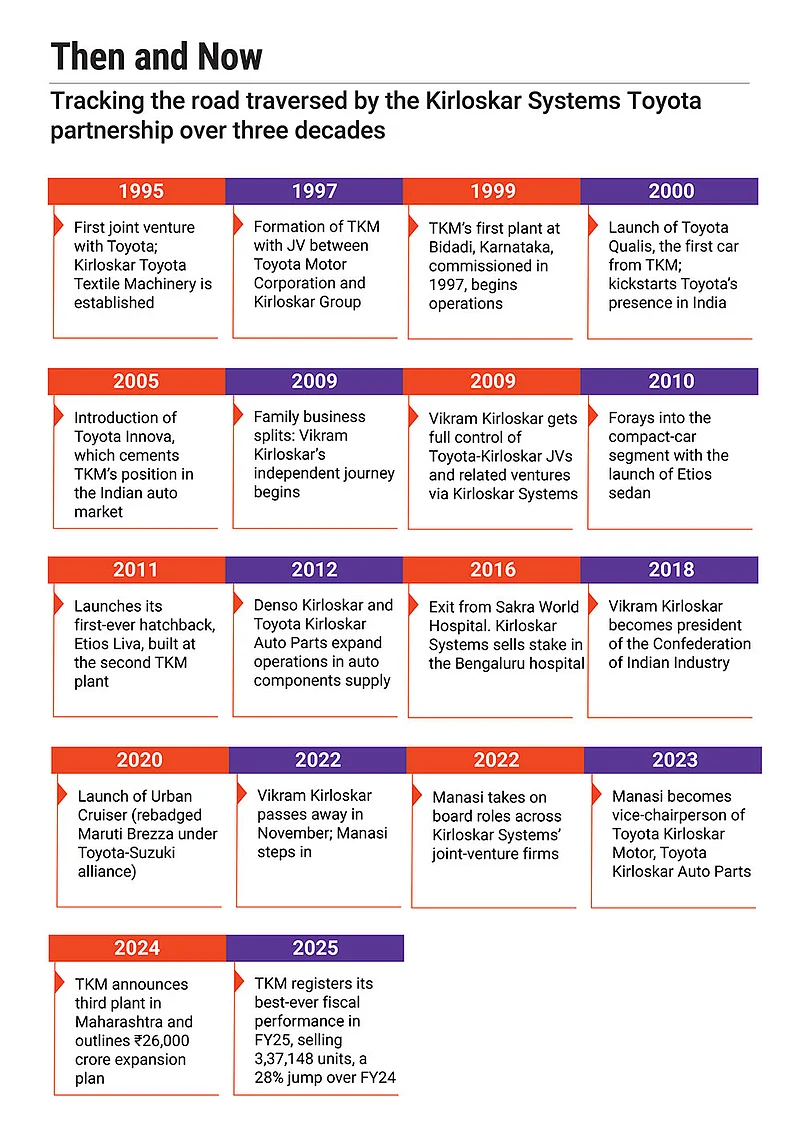

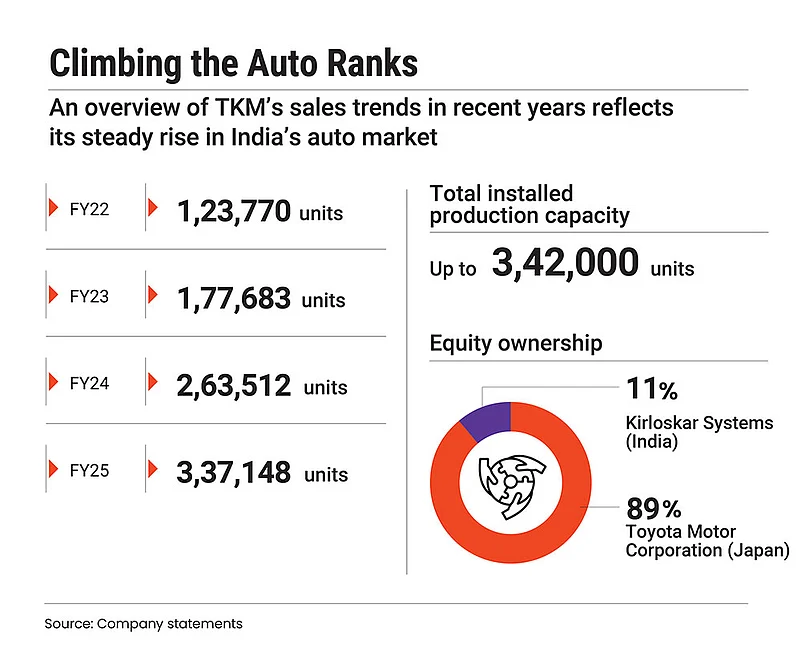

Manasi’s current role is deeply tied to the legacy her father built, both within Toyota Kirloskar and in India’s manufacturing sector. Vikram Kirloskar was one of the most prominent figures in post-liberalisation Indian manufacturing. He helped bring Japanese auto giant Toyota to India in the late 1990s when global automakers had just begun to test the waters of a newly liberalised market. TKM was officially incorporated in 1997 with Toyota Motor Corporation holding an 89% stake and Kirloskar Systems the remaining 11%.

The company’s first plant began operations in 1999, and in January 2000, Toyota launched its first model in India, the Qualis. At a time when sedans like the Honda City and hatchbacks like the Maruti Zen and Hyundai Santro dominated urban aspirations, the Qualis stood out. Boxy and practical, it became a dependable workhorse for families and fleet operators. Within a year, it had captured 35% of the multi-purpose vehicle (MPV) market. By the time it was discontinued in early 2005, it had sold over 1,40,000 units.

The Qualis laid the foundation for two vehicles that would go on to become icons in India’s automotive landscape—the Innova and the Fortuner. Launched in February 2005, the Innova redefined the MPV segment, while the Fortuner cemented Toyota’s place in the premium sports-utility vehicle (SUV) space. Together, they helped Toyota find its footing in India’s fast-evolving auto market, even as the company prioritised profit over rapid scale.

Globally, Toyota continues to lead the auto industry, selling 10.8mn vehicles in 2024 and retaining its crown as the world’s top-selling automaker for the fifth straight year. But in India, it took a slower, more measured path.

“For Toyota, profitability has always been one of the key priorities,” says Puneet Gupta, director, India and Asean automotive market, S&P Global, a financial-intelligence firm. “That’s why they’ve focused on larger vehicles like the Innova and Fortuner, and earlier Qualis. Their brand strategy has always leaned towards the niche segments,” he says.

This deliberate approach helped build strong brand equity but also limited Toyota’s reach. It lacked presence in high-growth categories like hatchbacks and compact SUVs. For years, its market share hovered around 4%, well behind mass-market leaders like Maruti Suzuki and Hyundai. In 2016–17, TKM sold around 1,42,500 units.

“When they [Toyota] entered India, Kirloskar was a strong partner. Through TKM they are able to explore and grow in the world’s third-largest auto market. TKM and Manasi are the key for the company’s growth in India,” says Gupta.

For Toyota, the global alliance with Suzuki, was a game changer. In India, that translated into a portfolio-filling strategy. With Suzuki’s deep roots in the small-car segment, Toyota found a way to address its weak spots. It began rebadging successful Maruti Suzuki models, starting with the Glanza (based on the Baleno) in 2019 and the Urban Cruiser (based on the Brezza) in 2020, offering Toyota-branded alternatives in price-sensitive segments where it had no previous presence.

“This partnership has fundamentally reshaped Toyota’s India strategy…Rebadged Maruti models now account for 54.3% of Toyota’s India sales, a sharp jump from 37.2% in 2019–20. The partnership has been the game-changer for Toyota’s mass-market success,” says Ravi Bhatia, president and director, JATO Dynamics, an automotive analytics firm.

Finding Her Footing

More than two years into the role as vice-chairperson of TKM, Manasi is steering the automaker through a period of disruption, where electrification, digital innovation and global supply chain shifts are redefining the rules of the game.

Under her watch, TKM has regained momentum in India’s hyper-competitive auto market. In 2024–25, the company posted its highest-ever domestic sales of over 3.37 lakh units. It is now among the top-five carmakers in India with a market share of over 7% (as of June 2025), its highest ever.

TKM has sold over 1.59 lakh vehicles in the first six months of 2025, a strong 15.4% growth year-on-year, according to JATO Dynamics.

Under her watch, TKM has regained momentum in India’s hyper-competitive auto market. It is now among the top-five carmakers

“The Indian market has become strategically crucial for Toyota globally. Hybrid cars and the tie-up with Suzuki bumped up TKM’s profit 3x in 2023–24,” Bhatia says.

But questions remain: can Toyota accelerate enough to meet India’s evolving expectations? For Manasi, the challenge isn’t just catching up, it’s about doing so while preserving long-term brand strength.

“AI and associated technologies create numerous opportunities to shrink product development timelines, increase quality and speed in production through improvements in efficiency of automation systems…At the same time players who are slow in embracing these, risk getting left behind,” says Ashim Sharma, senior partner and head (business performance improvement), NRI Consulting.

Decisions around what technology to back, when to localise and where to invest are largely influenced at the country level. “Ultimately, while strategic decisions may be made globally, it’s the local leadership that needs to respond quickly to market shifts, engage with policymakers and maintain strong government relationships. That agility can only come from Indian leadership on the ground,” says Gupta of S&P Global.

He added this is what Manasi will need to focus on, because being late to market, even with strong products, can be disastrous. For example, Honda is not doing too well in the Indian market, not because they lack good products, but because they were consistently late. For TKM, local commitment is visible in investment numbers. Manasi says that Toyota group companies have invested over ₹16,000 crore in India so far, including ongoing investment of ₹3,300 crore in a third plant.

The Road Ahead

As Manasi settles into her role, the question is no longer whether she belongs at the table. The real test is how she navigates an industry being reshaped by shifting consumer demand, electrification, AI and volatile global supply chains, while staying true to the values her father believed in.

Global auto dynamics are shifting fast, and India is becoming increasingly strategic for Toyota. “Even today, India is helping Toyota make up for market share losses they’re facing globally…Through TKM they are able to explore and grow in the India market. They have increased their market share aggressively in India,” says Gupta.

That momentum carries its own pressure. “The challenge now, especially in a market like India, is the shift to EVs, which is clearly the direction forward,” Gupta adds. While many rivals bet big on electric, Toyota leaned into hybrids, particularly in India where the charging infrastructure and fuel efficiency make them a more practical choice for now. With an 80% share of the strong-hybrid market, TKM’s hybrid-first strategy has paid off for now.

“Toyota’s hybrid-first approach is proving highly successful in India. It dominates India’s hybrid-vehicle segment with more than 84,000 units sold in 2024,” says Bhatia. While the hybrid penetration in India’s passenger vehicle segment remains around 2.5%, it is expected to rise significantly as fuel prices remain volatile and urban emissions become a critical issue.

As EV adoption accelerates and more competitors enter the hybrid space, Manasi and her company could face new challenges. Their success will depend on maintaining cost competitiveness, balancing hybrid focus with eventual EV transition and continuing to leverage the Suzuki partnership effectively.

“For Manasi the key challenge will be how she can deepen the partnership with Toyota. They need to adapt to India’s shifting automotive landscape across powertrain technologies,” says Gupta.

Supply chains are another pressure point. With EV components heavily reliant on China, Manasi will need to navigate and balance supply chains from Japan, China and other Asean markets, Gupta says. Export potential from India also needs to be a focus. “Toyota Kirloskar needs to play a bigger role in the company’s global roadmap,” says Gupta.

India also needs players like Toyota to prevent the market from tilting towards Chinese dominance.

Staying the Course

Through all this, Manasi believes technology is a tool, not a destination. “We believe there is no single technological solution and for achieving carbon neutrality at the earliest. We must consider all technologies that best meet local conditions, energy mix and the diverse mobility needs of consumers,” she says.

Manasi believes two and a half years is too short to judge her contributions, but she’s grown as a leader. One of her biggest lessons, she says, has been learning when to step back. “There are times, I feel like I know better, maybe because I am younger or have a better understanding of certain things. But I hold back…Experience carries equal weight. In the past two and a half years, I’ve learned how to manage my ego and how to focus on what’s best for TKM.”

What makes her leadership story different isn’t just that she’s young, or one of the few women running a legacy business in India’s male-dominated auto sector. It’s that she stepped into this role in the middle of a personal loss, without a playbook and chose to stay the course.