In the fictional world of Frank Herbert’s Dune, Arrakis is a mythical desert and home to the universe’s most-coveted resource—spice. Beyond its psychedelic properties, it is the fuel for space travel, so valuable that empires rise and fall for its control.

In the real world, deserts may never fuel space travel, but they can propel nations to a utopia, just as rarefied—decarbonised and emission-free. For evidence, picture this.

As the sun beats down on Rajasthan’s Thar Desert, millions of photovoltaic silicon panels light up and turn into a shimmering ocean of energy in Bhadla, Jodhpur, home to the world’s third-largest solar park. Spread across 5,700 hectares, this awe-inspiring facility pumps out 2.25GW of power, enough to light up 1.5mn homes.

Given its surreal desert setting, it might be easy to mistake Bhadla for a spectacular mirage. Except that it is not. Nor are the dozen other parks dotting India’s blazing plains, which collectively make more solar power, behind just China (886.7GW) and the US (139GW).

However, if you think that is unreal, think again as India has set its sights on adding another 180GW of solar in the next five years—four times its record.

Here Comes the Sun

There were several drivers, but none more potent than two pieces of game-changing reform. “The introduction of a market-driven procurement model and reverse auctions, which awarded projects to the lowest bidder and shares to the second and third finishers, made the industry competitive,” says Ajay Shankar, distinguished fellow, The Energy and Resources Institute (Teri).

In and beyond Bhadla, the Thar is emerging as an electromagnet for India’s power players like ACME, which owns a massive power plant spread across 4,400 acre in Jaisalmer. The numbers are staggering: 37 lakh solar modules, 384 inverters and 1,200MW of green power that runs through 100 voltage step-up transformers before draining into the Fatehgarh pooling substation.

From here, high-density transmission lines relay the power to industries and homes within and beyond the state.

Once unimaginable, plants like these and the ones in Pawagada (2GW), Dholera (1GW) and Rewa (750MW) have now become inspiring symbols of India’s rise as a global solar powerhouse. “Given the turbulent geopolitical context, India’s unlikely achievement sends a strong signal that clear policy drives transformation,” says Shalu Agrawal, director of programmes, Council of Energy, Environment and Water (CEEW).

Rainbow of Reforms

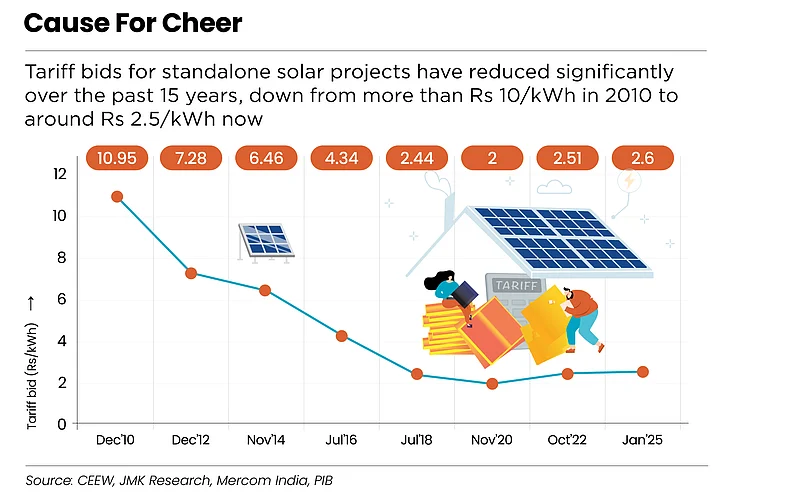

Eclipsed by a penumbra of financial, structural, regulatory and geopolitical challenges, India’s solar ambitions seemed most improbable in 2010, with tariffs hovering around Rs 10 per unit—three times that of coal—and investors staring at a forbidding mix of high risks and uncertain returns. Add to this the hefty capital requirements, a fickle regulatory environment, unproven revenue models and a storage infrastructure ill-equipped to cope with issues endemic to renewable power, such as intermittency.

To clear these clouds, the government rolled out a rainbow of reforms, such as reverse auctions that awarded the lowest bidder, halving tariffs to Rs 4.3–4.8 per unit in 2016 and later to around Rs 2.5 per unit, making solar remarkably competitive with thermal.

“When paired with batteries for storage, it [solar energy] remains among the most cost-effective 24/7 power solution,” says Amit Paithankar, chief executive of Waaree Energies, a solar-module manufacturer.

Similarly, the push for long-term power-purchase agreements (PPAs) enabled the industry to prioritise market expansion over short-term profits.

To bolster domestic manufacturing of high-efficiency solar modules, the government introduced the production-linked incentive (PLI) scheme, which proved phenomenally successful, generating substantial investments and reducing India’s import dependence.

Analytics service provider Rubix estimates that imports of solar cells and modules declined by 20% and 57% respectively in the first eight months of 2024–25.

“Supply chains have improved, aided by government support to domestic manufacturers. Our 1,300MW Rajasthan solar project, for example, now runs on modules from our own Jaipur facility,” says Sumant Sinha, chief executive, ReNew, a Gurgaon-based renewable energy company.

The PLI scheme added a powerful impetus to government policies like the Domestic Content Requirement policy, which mandated local sourcing of solar cells and modules to fortify domestic supply chains. Complementing this are initiatives like Central Public Sector Undertaking Scheme, offering viability gap funding (VGF) to bridge the cost disparity between domestic and imported components and the Pradhan Mantri Kisan Urja Suraksha evam Utthaan Mahabiyan (PM-Kusum), which makes domestic components mandatory for setting up decentralised solar-power plants.

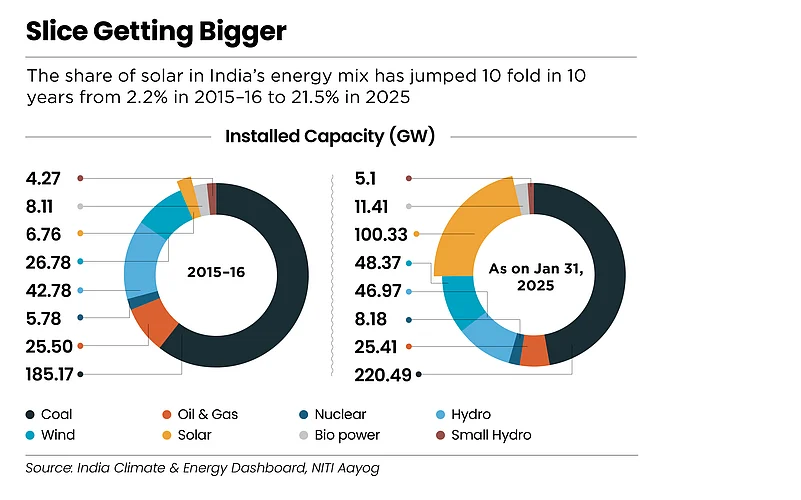

Buoyed by these policies India is now the third-largest solar-power producer globally, with solar energy forming 20% of its total power-generation capacity.

A massive $18.9bn in foreign direct investment has surged into the renewable space since 2000, $3.8bn of it in 2023–24 alone, representing a 51% annual jump. The renewable sector now employs 1mn-plus people, 318,600 of whom are in the solar vertical.

Task Cut Out

As part of its Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs), India needs to expand the renewables portion of its total installed energy capacity to 50% by 2030. Given that renewables are already at 47%, it is on track to stroll past this milestone way ahead of time. The target it has set for itself—180GW in five years—is, however, daunting.

But why is India chasing such impossible targets? According to brokerage house Nuvama Institutional Equities, the country could face an acute power deficit around 2029–30, even if demand grows by a conservative 5% year-on-year. But with the rapid shift to electric vehicles (EVs) and the explosion of data centres, demand is set to rise much faster, leaving India with no choice but to scale up its solar-led renewables capacity exponentially, far beyond its NDC pledge.

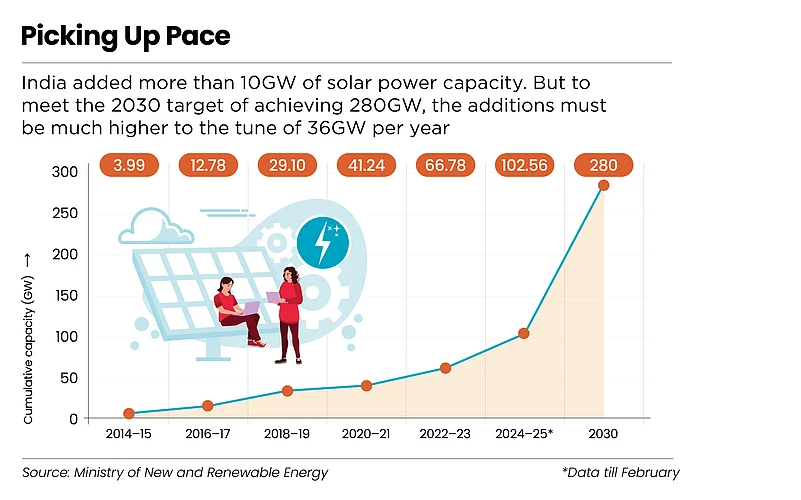

In numbers, adding 180GW by 2030 would require sustained solar additions of 36GW per year, a breakneck speed that far exceeds current levels, pushing India into uncharted territory.

“Total backward integration for solar, wind and battery would be important to gain control over the cost of each component and ensure stable prices and timely deliveries,” says a spokesperson of Adani Green Energy, the country’s renewable energy leader.

Clearly, the path ahead is strewn with challenges, none more fraught than finance. There are concerns around infrastructure, storage, land acquisition, regulatory frameworks, bureaucratic inertia and supply chain vulnerabilities too.

Shoring up Finances

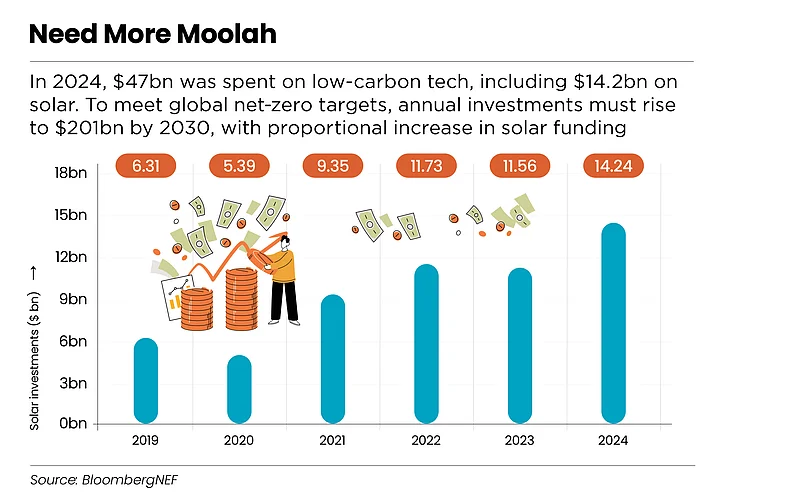

To get a sense of the staggering funding challenge, consider this: according to Outlook Business estimates, the country will need to muster $155bn in fresh investment to go from here to 280GW.

Mobilising funds of this magnitude would entail coordinated action of banks, private-equity players and multilateral lenders on an unprecedented scale.

Sure, policies like VGF and PLI have been instrumental in catalysing early growth. But given the enormity of the 2030 challenge, a much bigger role would have to be played by private investors, who, while showing interest, have tended to stay on the sidelines, baulking at the prospect of policy volatility and currency risks.

“Beyond banks and NBFCs [non-banking financial companies], private-equity players like Blackstone and Temasek invest in renewables, but they prefer cash-generating assets,” says Ashwini Kumar Tewari, managing director, State Bank of India (SBI).

But how about the exposure of SBI itself in the sector—a mere 4% of its loan portfolio as of February 28? Actually, not bad at all. “The Rs 59,274 crore we loaned to renewables in this period represented a 64% jump over the previous year, with solar alone hogging Rs 43,800 crore,” says Tewari.

Institutions such as the World Bank, Asian Development Bank and International Finance Corporation would raise their ante significantly if India structured bankable projects with assured, long-term returns. Green bonds and environmental social and governance (ESG)-driven investments have shown promise and given a stable regulatory environment, they could make a difference. But there is a caveat.

Lengthy Shadows

“Access to green bonds depends on financial strength. Top-rated companies like ReNew can secure green-bond funding at lower costs, while smaller, lower-rated firms may struggle,” says Tewari.

Just as worrying is the fact that funding for the renewable energy sector from banks and other public-sector lenders has thus far been lopsided. Sure, the past decade has seen growing interest from private-equity entities, including global investment and pension funds, and independent power producers like Adani, JSW Energy and Tata Power—but that has scarcely made a dent with debts still making up 75% of the investments.

Adding 180GW by 2030 would require sustained additions of 36GW per year, a breakneck speed that far exceeds current levels

“During the six-to-18-month construction phase, lenders are exposed to greater risks,” says SBI’s Tewari as it is marked by substantial upfront investment and may be affected by construction delays, regulatory hurdles and market fluctuations. Project mismanagement, engineering design flaws and rising interest rates further exacerbate these risks.

Another disturbing factor is undersubscription (bids for planned projects falling short of the offered capacity) or, more specifically, its underlying causes, which are essentially bureaucratic inertia, infrastructural bottlenecks and the reluctance of beleaguered state distribution companies to commit to long-term agreements.

“Due to the expectation that the prices might fall further, discoms don’t tie up for long-term contracts, creating off-taker risk for the developers,” says Vibhuti Garg, director, South Asia, Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis (IEEFA).

In the past year alone, undersubscription surged five-fold to 8.5GW in tandem with project cancellations that stood at a staggering 38.3GW of planned renewable capacity between 2020 and 2024, with 2023 being the worst year.

Forty key transmission projects are currently in limbo due to delayed power transmission approvals and clearances, stalling connectivity to renewable energy projects. Worse, the impending expiry of the Inter-State Transmission System (ISTS) waiver in June 2025 is likely to raise costs for developers, making new investments less attractive.

Fixing the Grid

Even if India wins its battle for funds, it will still need to fight fires on other fronts, such as transmission and storage. “Evacuating power to the grid requires transmission capacity, substations and a smarter grid, which must evolve to manage complexities and ensure stability,” says Waaree’s Paithankar.

With its grid infrastructure growing at a far slower pace than its renewable energy generation capacity, India faces an alarming mismatch that leaves a great deal of the power it generates stranded. Take, for example, the states of Rajasthan and Gujarat, where generation has long outstripped the capacity of their grids to evacuate power, leading to a loss of up to 10% during peak sunlight hours. This gap is set to widen disconcertingly unless India ramps up its high-voltage transmission networks at pace with its expanding solar-power-generation capacity.

The much bigger headache still is storage. Solar energy is genetically intermittent and, therefore, without a robust storage infrastructure aligned with generation capacity, much of the green power India produces could go to waste.

“As the share of solar power increases in the country’s electricity mix, it will need to be rapidly shored up to balance supply with demand and ensure smooth grid integration,” warns Rohit Gadre, specialist–solar at research agency BloombergNEF.

According to multiple sources, for its installed capacity of 100GW, India must have an energy storage system (ESS) capacity of 113GW hours (GWh). Currently, its capacity stands at less than 1GWh. Looking ahead, India would require an estimated 336GWh of ESS capacity by 2030. The opportunity is not lost on the industry leaders.

“We aim to develop battery storage solutions and a 5GW+ hydro-pumped storage project [PSP] capacity by 2030. Already, we have a pipeline of hydro PSPs across Andhra Pradesh, Maharashtra, Tamil Nadu and Telangana,” according to Adani Green Energy.

Stumbling on Storage

Historically, the storage industry has been hamstrung by high costs and over-dependence on imports from countries like China for lithium, the lifeblood of batteries, exposing the industry to price shocks and supply disruptions.

Although the government has stepped in to charge up the power storage industry with measures like the new firm and dispatchable renewable energy (FDRE) tenders, which mandate power companies to bundle storage systems with their bids for projects, the results have been less than impressive. “Storage capacity addition must outpace early solar growth, and storage bid volumes must exceed new solar capacity,” says Teri’s Shankar.

Lithium alternatives like sodium-ion and solid-state batteries hold promise but are yet to prove their mettle at scale. The more established pumped-hydro storage comes with its challenges like high capital costs, long gestation periods and environmental concerns. Unless India addresses these issues in a mission mode, its lofty solar ambition faces the risk of major delays or disruptions.

Upstream, import tariffs have driven up the costs of solar cells and modules, and not just in terms of cash. Technologically, too, India lags its global peers.

For example, China has started shifting from the traditional Passivated Emitter and Rear Contact (PERC) technology to Tunnel Oxide Passivated Contact (TOPCon) for better efficiency and durability and Heterojunction Technology (HJT). However, manufacturers in India are still in the PERC age.

On Shaky Ground

Many large infrastructure projects in India have landed in hot water, literally, because they haven’t found the ground to stand on, with land acquisition proving to be an intractable challenge involving a thicket of sanctions, approvals, compensations and land-use conflicts.

For land-hungry solar power projects, such delays could be deadly. A typical solar farm needs 5,000 acres per gigawatt of power. In other words, for its ambitious target of 280GW of installed solar capacity, India would need about 1.4mn acres of free land—roughly eight to 10 times the size of Delhi.

“Finding contiguous land near substations is a major hurdle—fragmented parcels raise costs. With rapid sector growth, land procurement is getting harder, driving up right-of-way and real estate costs. Greater transparency and ease in allocating government land would help immensely,” says ReNew’s Sinha.

The bidding process complicates the issue further as it tends to favour developers who own the land required for a project. This escalates capital costs with funds locked in for extended periods before a project even starts. Meanwhile, government intervention remains minimal.

“In any infrastructure project, land acquisition has always been a challenge. However, some of the states have been forthcoming and have offered government land for renewable energy projects including solar parks,” says Nikhil Dhingra, chief executive, ACME Solar, a major renewable energy company.

Another major challenge is securing the right of way for transmission lines, which must traverse areas governed by state governments, local authorities and private agencies.

Despite these challenges, land acquisition constraints are expected to ease over time, helped by shifts in policy and technology.

Innovative models are also emerging to reduce land dependency, such as community-owned solar projects, where farmers co-invest or leverage their land to generate and sell solar power.

Another potential game-changer is floating solar, which eliminates land acquisition challenges. By using water bodies floating solar farms provide a vast, untapped resource for expansion.

Still a Long Way

Although renewables including solar are hogging the limelight, fossil-fuel-energy sources like thermal are set to be at the centre stage of India’s energy theatre for the foreseeable future. They must if India wishes to maintain a 7–8% growth momentum over the next decade. What India cannot afford, however, is to lag behind in the global transition race and it must, therefore, do what it takes to keep pace with, if not lead the frontrunners.

Efforts are already underway to address challenges in energy storage, transmission and beyond. To emerge as a preferred destination for impact investors, India is ringing in reforms, stabilising its regulatory framework and taking steps to cushion the industry from currency and geopolitical shocks.

Meanwhile, standalone storage tenders are gaining ground and innovations addressing lithium shortages for battery storage are emerging. “Alternative technologies like flow and sodium-based batteries are already in the works,” says Garg of IEEFA.

After developing a kilowatt-scale vanadium redox flow battery for grid-level storage, researchers at premier engineering institutions, including IIT Madras, are now exploring alternative flow battery chemistries using lead, zinc, iron and organic redox-active materials to cut costs. In collaboration with Hindustan Zinc, the institute is also developing a rechargeable Zinc-Air battery prototype—praised for its affordability, safety and long-duration storage.

“India’s solar industry needs a mix of government incentives and industry-led initiatives. Capital subsidies, lower electricity costs, affordable land and low-cost funding are key,” says ReNew’s Sinha.

Alongside, the domestic supply chain needs to be strengthened and diversified with an emphasis on Make in India if the country aspires to become the Arrakis of the world—a self-sufficient global supplier of a coveted resource that is reshaping life itself.

Rooftop Solar: Waiting to Shine

Residential rooftop solar can be a game-changer in navigating the land availability challenge for utility-scale solar projects and reaching the 2030 target. But its adoption remains limited. As of January 31, grid-connected rooftop-solar capacity was 16.3GW, far from the targeted 40GW by 2022.

The biggest hurdle is the high upfront cost, at least Rs 2.5 lakh for a 5kW solar unit, while the monthly electricity bill of an average household rarely exceeds Rs 5,000. Plus, the presence of a reliable round-the-clock grid-connected power supply provides little incentive to shift.

Programmes like Pradhan Mantri Surya Ghar Muft Bijli Yojana, which provide subsidies and also has the provision to offer collateral-free loans of up to Rs 2 lakh at an interest rate of 6.75%, are promising. It has driven 10 lakh installations as of March 10 and the target is to reach 1 crore households by 2026–27.

But other challenges still remain like grid connectivity. Rooftop solar requires a two-way flow of power with the surplus power flowing back from the household to the grid. Experts say the distribution grid may not be strong enough to handle two-way power flows, causing grid-management problems.

Moreover, the awareness about skilled installers and maintenance still remains low. “It is almost impossible for a customer to know what the quality of the workmanship is when they are setting up a rooftop plant. The issues only become clear 3–5 years later,” says Rohit Gadre, an expert on renewables financing with research agency BloombergNEF.

For rooftop solar to truly capture the Sun, faster smart meter rollouts, stronger distribution grids and stricter installation standards are required.