Five years ago, a company scripted a remarkable turnaround. Its market cap had plummeted from $1 billion when it listed to $8 million following the 2001 crash, trading at less than a $1 per share. The company Concur, which had begun by selling applications on CDs and floppy disks, decided to dismantle its business model and try a whole new one called SaaS (software as a service). It was essentially a change in delivery. Instead of shipping across bubble-wrapped CDs, their updates and newer version of the business-expense-reports application could now be accessed by their clients online, like you would a shopping site, on a browser. It drove up their revenue to $600 million in little over a decade and then SAP bought it in 2014 for $8.3 billion to bolster its presence in cloud computing, an area it could no longer ignore. SAP’s CEO Bill McDermott had called it the best business case he had ever put forward to the board.

Around the time McDermott was building his friendship with Concur’s co-founder Steve Singh, perhaps warming him to the deal, Marc Andreessen of venture capital firm Andreessen Horowitz wrote an article titled “Why software is eating the world”. He attributed software’s gigantic leap in influence to SaaS, with more and more conglomerates running on software that was delivered easily, as an online service. Much like we watch movies now on Netflix, rather than walking down to the nearby video or CD rental.

With SaaS, companies no longer spent weeks or months installing complex software on desktops (remember the frustrated IT department staffer egging the workstations to update faster?). The SaaS provider, for a subscription fee, hosts the application at its data centre and customers access the software through a standard browser. The updates are done at its end too. This means zero capex, no hardware installations and ease of integration. Most leading SaaS companies publish their APIs (application programming interfaces) that help applications or platforms talk to one another effortlessly.

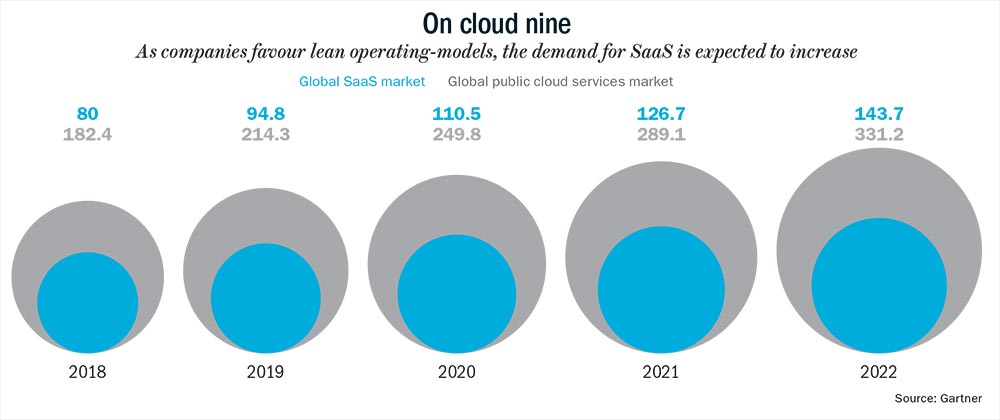

Little wonder then that there is an explosion of SaaS companies around the world, particularly in India. The global market is expected to grow from $80 billion in 2018 to $143.7 billion in 2022. It will nearly double over four years and, happily for us, India is perfectly placed to ride this wave. We have a large talent pool of software engineers, strong B2B experience from the IT services industry and a low-cost advantage. Therefore, Indian SaaS start-ups are already building best-in-class products that compete globally, and three — Freshworks, Druva and Icertis — made it to the unicorn list during the past year.

In favour

There are many small businesses with big ambition and the SaaS opportunity is an ideal fit. The hardware that this service needs to run, cloud-computing infrastructure, has been made cheaper by Amazon Web Services (AWS), and now by Microsoft and Google too. They are renting out computing, storage and network capacity by the hour. Therefore, any enterprising start-up can build products on this, without breaking their piggy banks on data centres or time-consuming customer installations. “It is beneficial that you are built on top of AWS because that assures the clients of a certain level of dependability, the rest depends on your ability to leverage the infrastructure. So we were able to build on the shoulders of giants rather than starting from scratch,” says Krish Subramanian, CEO, Chargebee.

The cloud may come cheap but are companies migrating? Yes, in fact, there is a rush. According to global research firm Gartner, the global public cloud market, estimated to be around $182.4 billion in 2018, will reach $331.2 billion by 2022 (See: On cloud nine). More than one third of the organisations surveyed by Gartner claim that cloud investment will be one of their top three investing priorities and, by the end of the year, over 30% of technology providers’ new software investments will shift from cloud-first to cloud-only.

Traditional, ‘grounded’ enterprise-resource planning (ERP) systems are anyway failing to meet the needs of the online-first business models of today. For example, when earlier businesses merely needed to bill their buyers, today they would like to understand their shopping behaviour or preference in payment methods to ensure customer loyalty.

Even long-established industries are re-architecting their processes in sales, finance and HR. Enterprise clients are definitely changing their buying behaviour, and that is helping these startups in spades, especially in finding customers in distant countries. “Customers are now comfortable buying software from anyone anywhere. So, early-stage companies are able to validate the product-market fit from here,” says Chargebee’s Subramanian. The firm provides subscription billing services to clients across the world. “Global brands such as FedEx, British Petroleum and Robert Bosch are clients and we haven’t even met them till date. They found us online. Of course you have to tick all the boxes in terms in hygiene factors such as product quality, water-tight terms of service, legal contracts and support services. But there is a huge shift in mindset,” he adds. The firm, which currently processes over $2 billion of customer revenue, is looking to double that number in the next year.

“Technology has shrunk the distance to nothing,” says Suresh Sambandam, CEO and founder of OrangeScape whose work-automation and collaboration platform helps businesses manage their entire workflow on a dashboard of sorts, and create a digital workplace. “Sitting in Chennai or Bengaluru or Hyderabad, you can market to the world through digital marketing. So you acquire customers riding the digital wave and then service them remotely.” The company services over 10,000 customers including Pepsi, Motorola, Danone and Michelin in over 160 countries, out of its centre in Chennai.

Firms are benefitting from shrinking of distances and from corporate IT spends moving fromtop-down to bottom-up. Software developers who use the solutions on a daily basis, and not CEOs and CIOs, choose what to buy and they decide after trying out many options online. Earlier purchase decisions were taken by senior executives who needed to be wooed for months by a highly motivated sales team. “As a result of browser moving to the web, good products win now instead of a good sales pitch,” says Abhinav Chaturvedi, partner, Accel whose firm has been a pioneer investor, backing companies such as Freshdesk, Chargebee, Zenoti and BrowserStack which are building global products out of India.

The tailwind notwithstanding, a SaaS start-up can only be successful if it ensures that customers are using its product consistently, keeping the revenue growing and churn rate low.

Sambandam believes that SaaS companies can be a trillion-dollar opportunity for India and draws a parallel to the IT-services boom. “We have an opportunity to create another Infosys moment. Over the past three to four decades, thanks to the IT services boom, we have built deep domain expertise in almost every industry, which is what we need to build products and make a global SaaS hub.”

Following the IT services boom, the outsourced product development wave began in the early 2000s, when global giants such as Microsoft and Adobe started their offshore development centres in India. While they started out with low-end testing jobs, their Indian arms graduated to building products from scratch and lot of the engineers who worked at these centres were witness to the beginning of the cloud transition, which led to India’s SaaS boom. “The transition from IT services to outsourced product development gave software engineers the confidence that they can build products for the global market. They understood that the technology is global and the low-cost advantage that India offered was a distinct competitive advantage,” says Sameer Brij Verma, managing director, Nexus Venture Partners.

Sambandam believes if there is a robust ecosystem, more solution architects will leave their cushy jobs to start SaaS companies. Chennai, known as the SaaS capital of India, has managed to create such an environment and therefore has spawned over 600 companies in this space. In this city, SaaS companies generate over a billion dollars in revenue and employ around 15,000 people.

Leading the wave

A lot of them owe their entrepreneurial journey to Zoho which began its journey as Advent in 1996. It was an early mover in this space and its employees were part of the transition from desktop software to SaaS. Just as the PayPal Mafia went on to create billion-dollarcompanies in the US, the Zoho mafia went to build more than 20 start-ups in Chennai. “Technology development was such that we had to go global from day one. So we not only had to think about product strategy, we had to think through all aspects including sales and marketing, and how we could service clients across various time zones,” says Sridhar Vembu, founder, Zoho.

While the company started out by providing network management systems, it launched enterprise IT products post the dotcom recession in 2000. In 2005, the company began offering customer-resource management (CRM), product management and invoicing through its division, Zoho.com. As the division gained momentum, the company was rechristened Zoho. According to Vembu, the company saw an opportunity in CRM where SMBs (small and medium businesses) were paying through their nose for on-premise management. “We saw that, in CRM, existing vendors were expensive and came with lock-in periods, so we came with an offering that was more affordable with a strong support team based in India. You have to identify a customer segment that allows you to shine early on, and use that success to expand your product footprint,” he says. From being a CRM player, they now offer an entire suite of more than 40 business applications through Zoho One on which enterprises can run their entire business. Zoho One was launched in 2017 with the goal of becoming the operating system for smaller businesses offering the software at $30 per person. Today, the company has 45 million users and clients such as Amazon, Facebook, L’Oréal and KPMG.

Weighing the risks

For many entrepreneurs, the first dilemma they face when they start out, is what problem should they solve. Do they go after an untackled problem, or an already attempted one with a better proposition and at a competitive price? The first may appear more glamorous but is also a lot riskier, because you have to create the demand and convince customers. For instance, when Salesforce launched its offering in 1999 targeting SMBs, it wasn’t taken seriously but once it was able to popularise the concept, it quickly went on to become the largest CRM player in the space.

Early entrants such as Zoho and Freshworks decided to go after an existing problem where customers were willing to pay for a solution. While Zoho chose CRM, Freshworks started with a customer helpdesk and initially went after the SMB segment. “We realised that there was a long tail of SMBs that were underserved,” says Girish Mathrubootham, founder, Freshworks. He knew that blindly following the Silicon Valley model while selling to SMBs will not work. “Catering to SMBs required a different approach to design thinking. We can learn many things from the companies in the Valley, but Indian companies need to innovate to make products globally affordable and appealing,” says Mathrubootham. The company focused on designing software that is intuitive, affordable and easy to integrate with existing applications and their approach worked. Today, the company has over 220,000 clients including companies such as Honda, Bridgestone, Hugo Boss, Toshiba and Cisco. While they started as a single product — a customer helpdesk for SMBs — they quickly morphed into a multi-product company offering a suite of enterprise solutions including those for management of IT services, call centre sales and marketing. In 2015, the company realised that large enterprises, too, were signing up for their products online. As the mid-market engine started to gain momentum, the company hired a team to drive enterprise sales and filled product gaps to suit their needs. InAugust 2018, powered by a total funding of $250 million, Freshworks became India’s first SaaS unicorn with a valuation of $1.5 billion.

But, unlike consumer tech, you don’t need a tonne of capital to scale up a SaaS business. It is more capital efficient and can grow fast on internal accruals. “SaaS has a gross margin of 85%. So for every dollar earned, you are able to invest 85 cents back in the business and the customers pay you upfront, so your cash flows are 12 months ahead,” says Chargebee’s Subramanian.

That said, having the extra cash never hurts, like in all businesses. It can help a company scale up faster like it did Freshworks, which took just over five years to grow from $1 million to $100 million in revenue. On the other hand, Zoho chose to do the slow climb — the company which currently clocks over $500 million in revenue, managed that feat in 23 years. Freshworks in all probability will hit that milestone much sooner as it continues to expand rapidly across customer segments, markets and products. Zoho’s Vembu stands by their measured approach. “A lot of people tell me we could have scaled up faster if we had taken funding… but I feel companies with a lot of capital lose their financial discipline, sometimes by overhiring or building fancy offices. So, we stayed away. Besides, this gives you the freedom to execute without worrying about quarterly numbers,” he says.

Big-game chasers

Just as Zoho and Freshworks started with the SMB segment and then moved up, there’s another breed of SaaS companies such as Capillary Technologies, Eka Software Solutions and now Zenoti, who focused on large enterprises from day one.

These companies go after big contracts and hence the sales cycles are longer. In some cases, they are focused on a single industry vertical. For instance, the average contract value for Capillary Technologies which focuses on retail and consumer product companies is around $120,000 and the average sales cycle is around six to nine months. These contracts typically span three to four years. In contrast, SaaS companies that focus on SMBs usually have sales cycles of only a month. “These companies (that chase bigger deals) need to work with a couple of global enterprises initially to get the product-market fit right. Since, most often, they are building a solution for a new category… they need to get it right, and then adapt it for more companies in that space,” says Nexus’ Verma. The fund has been an early investor in SaaS companies such as Druva, Postman and Eka Software.

While the sales cycle may be longer when servicing larger enterprises, the entry barrier in this space is much higher. “We don’t compete on price and sometimes it takes two years just to meet compliance requirements, and that creates an entry barrier of sorts,” says Manav Garg, founder, Eka Software. “We see a massive opportunity in legacy industries, be it commodity management, treasury and banking. These are mission-critical functions,” says Garg. Eka Software, which provides commodity-management solutions, has Rio Tinto, Cargill, Bunge and Petronas on its client list. Its product helps with sourcing, trading, risk management and operations, and currently clocks a revenue of around $20 million.

Unlike most SaaS companies for whom the Holy Grail is the US market, Capillary Technologies built its business targeting emerging ones. It did try its hand in the US in 2014, after raising $14.5 million, but couldn’t achieve the scale needed in the competitive landscape and decided to focus on four other markets — India, Middle East, South East Asia and China — instead. “Our offering was more suited for these markets, where retail is still a sunrise industry and customers are willing to invest in newer technologies,” says Capillary Technologies co-founder, Aneesh Reddy. It began operations in 2008, with a customer-loyalty programme for retail and consumer-product companies, and now helps retailers by providing them timely insights for marketing campaigns, with inputs from point-of-sales machines. Today, it counts major brands such as KFC, Pizza Hut, Puma, Starbucks, Levi’s, Bata, Lee and Wrangler as its clients. The company powers Pizza Hut’s and KFC’s e-commerce business in 12-13 countries.

“About 45% of our incremental business last year came from existing customers. Asia is more of a solution and outcome-based market, where customers prefer to deal with a single or few vendors, unlike in US where people want best of breed solutions and spend a lot of time integrating them. So, every time we added more parts to our product offering, our customers bought more from us,” he says. Needless to say, SaaS companies have to keep pace with the fast-paced change in technology. Milind Borate, co-founder of Druva, which entered the coveted unicorn club this June, says the firm’s ability to adapt to the needs of the changing market has been one of its growth drivers. The company had started by providing data protection and management services for laptops in 2008, and began offering the same through the cloud in 2011. Today, the challenge is the explosion in data and data sources. “A lot of the primary data is moving to the cloud, and there are a lot of SaaS applications where data is being created and stored. Last but not least, IoT has driven a lot of data creation as well. So we have extended the platform to cater to explosion in user data and also manage server data and infrastructure backup,” he says. It has over 4,000 clients and annual revenue just shy of $100 million, growing at 50%. “Apart from extending our product platform, what really helped us scale business was having a local marketing team that helped us understand what messaging will work and having a local sales team helped us speak the customers’ language,” adds Borate.

Focused play

Investors initially swore by horizontal SaaS start-ups offering solutions across various functions such as sales, marketing, customer and IT support since the businesses were addressing a large market opportunity. But with more businesses going online, thanks to smart phone penetration, frictionless payment options and cheap data plans, there is enough demand for SaaS companies focused on a particular vertical or industry. The next set of unicorns could even come from this space. Take the case of Zenoti, for example, which has developed a cloud-based offering exclusively for spas and salons. Founded in 2010, it is looking to clock $100 million in annual revenue in the next couple of years and that is just from one niche vertical. While it counts chains such as Lakmé, Kaya Clinic and Bounce as clients in India, 60% of its revenue still comes from the US. It has attracted investor interest, raising about $91 million in funding from marquee investors such as Accel, Steadview Capital and Tiger Global. In fact, it was Accel that nudged the firm, which until then focused on India and the Middle East, to go global. Sudheer Koneru, co-founder of Zenoti, says, “In a mature market, they expect the solution to work well and they favour value over price. India is more price-sensitive,” says Koneru.

According to him, Zenoti is the most expensive offering in the US market today but it is still popular, because it offers a comprehensive solution for customers to run their entire business rather than aggregating applications from multiple vendors. This is a unique India advantage. “If you are a company in the Valley, you would not be able to build such a comprehensive offering. You would run out of resources and that’s why companies there choose to specialise in a single product area,” adds Koneru. According to Eka’s Garg, while it could take $5 million in seed funding to build a SaaS product in the US, you could do the same for about $1 million in India.

Despite the inherent advantage, competing globally is no cakewalk for these companies. For one, traditional software giants such as Oracle, SAP, Microsoft and Adobe who were late waking up to the cloud phenomena are putting their cheque book to work. After re-architecting their products as SaaS offerings, they are chasing businesses of all sizes. And let’s not forget, the start-ups also need to contend with SaaS heavyweights Salesforce, ServiceNow, Workday and Zendesk. The behemoths now have a suite of offerings catering to the entire spectrum of large enterprises and SMBs. Platformisation, where they offer a suite of applications which can be accessed through a single window, is already gaining traction. “Given the democratic way in which software is being developed, a new product can challenge your existing market share anytime,” says Accel’s Chaturvedi.

However, given the ability of larger horizontal SaaS players such as Freshworks and Zoho to understand businesses and develop best-in-class products at a lower cost, they will continue to strengthen their presence in the SMB segment, while chipping away at the mid-market segment. For Freshworks and Druva, the next step is to list on the bourses. “We have the scale to go public but haven’t drawn up a definite timeline. There is massive opportunity to scale up revenue over the next two to four years, so we are focused on execution,” says Mathrubootham.

Challengers old and new will keep coming at them but, this time around, the advantage that Indian SaaS companies have is more than just cost-arbitrage. They now have the ability to develop IP and design products which in the right market can scale rapidly. What’s more, there is capital waiting in the wings to step in when needed. At least for now, it definitely seems like there is nothing stopping Indian companies from being a force to reckon with in the global SaaS market.