K Paul Thomas never imagined he would be hospitalised the day he took the vaccine jab. But, call it bad luck or the ferocity of the second wave, he was admitted in a facility in Thrissur, Kerala, that very day in April, diagnosed with the infectious respiratory disease. The MD & CEO of Kerala-based ESAF Small Finance Bank has since recovered, but he will need divine intervention to salvage the business of his bank, which has been ravaged by the pandemic.

The SFB’s profit fell 44.64% year-on-year to Rs. 1.05 billion in FY21 owing to higher provisions as gross non-performing assets (NPAs) surged to 6.70% and net bad loans piled up to 3.88%. “What can you do in a year in which the economy came to a complete standstill for 45 days and five months were lost owing to moratorium of repayments,” explains Thomas. While the bank, which donned a new avatar in 2017, was hoping that it would be business as usual in FY22, the sudden spike in cases since April has proved to be a bad start.

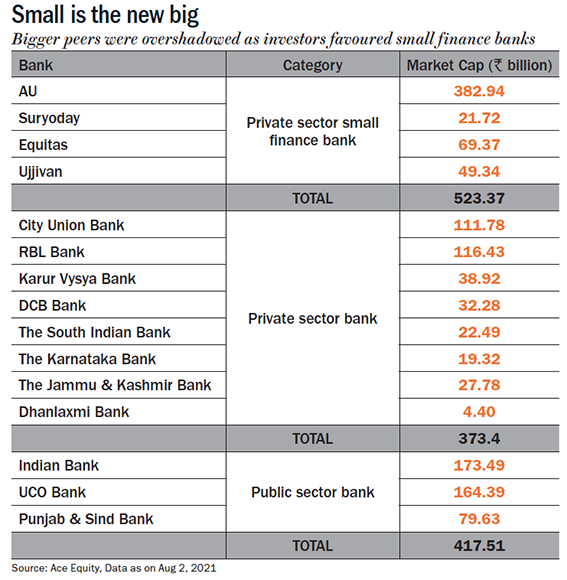

Till recently, SFBs were the toast of the market. For instance, the combined market cap of the four listed SFBs — AU, Equitas, Ujjivan and Suryoday — at Rs. 523.37 billion dwarfs the combined market cap of eight smaller private sector banks and three state-owned banks (See: Small is the new big). Post the second wave, the sentiment is changing — Ujjivan listed in December 2019 is trading at Rs. 29, below its issue price of Rs. 37, Equitas listed in November 2020 is trading at Rs. 63 compared to its issue price of Rs. 33 and Suryoday listed in March this year is trading at Rs. 203 below its issue price of Rs. 305.

Till recently, SFBs were the toast of the market. For instance, the combined market cap of the four listed SFBs — AU, Equitas, Ujjivan and Suryoday — at Rs. 523.37 billion dwarfs the combined market cap of eight smaller private sector banks and three state-owned banks (See: Small is the new big). Post the second wave, the sentiment is changing — Ujjivan listed in December 2019 is trading at Rs. 29, below its issue price of Rs. 37, Equitas listed in November 2020 is trading at Rs. 63 compared to its issue price of Rs. 33 and Suryoday listed in March this year is trading at Rs. 203 below its issue price of Rs. 305.

Nitin Aggarwal, analyst, Motilal Oswal Financial Services (MOFS), believes SFBs with a micro-finance focus will be particularly vulnerable. “COVID-19 has impacted SFBs that have had exposure to MFIs and anyone coming for a listing with an MFI background may not be in as good a shape.” That’s bad news for IPO-bound ESAF, an MFI-focused player with 85% of its loan book or Rs. 84 billion comprising micro loans.

While EASF had got Sebi approval in March, it refiled the draft red herring prospectus (DRHP) in July because of the pandemic with plans to list in H2FY21. “By then, hopefully, things will start looking better,” says Thomas.

Hope is a good thing but there is nothing much the SFBs can do as the economy battles its way out of the once-in-a-generation crisis. The pain for SFBs is much more acute given their customer segment — micro and small business owners. This is the very business MFI NBFCs wanted to get rid of, by turning into SFBs. But, it sticks like old gum.

Looking for a makeover

To drive financial inclusion, when the RBI allowed a new category of banks under SFB, a host of NBFC MFIs opted to switch because the new licence allowed them to raise public deposits, which meant cheaper funds compared to borrowings from banks.

Prakash Agarwal, head – financial institutions, India Ratings says, “On the asset side, MFIs could seamlessly transition to SFB without having any disruption in their portfolio. On the funding side, costs could come down drastically and there would be stability.” EASF’s Thomas has lived through those unstable times. He recalls, “Over my 25 years in the MFI sector, I have seen how liquidity can dry up suddenly. Today, we have CASA ratio of 19.4% and term deposits of around Rs. 70 billion, which would not have been possible as an NBFC.”

Yes, things are better than yesterday. But, they aren’t as expected. For one, raising funds has been tough for SFBs. They have to compete with the larger banks since the smaller banks’ small borrowers cannot be a rich source of deposits. Therefore, SFBs are forced to pay higher interest rates to look attractive to depositors. For instance, EASF is paying 8.75%, competing with public and private sector banks paying 3% to 4%. Thomas believes eventually his bank will be able to bring down its deposit rate. “We have a strong NRI client base and we have recently started a recurring deposit scheme for marginal customers with an amount as low as Rs. 100,” he says.

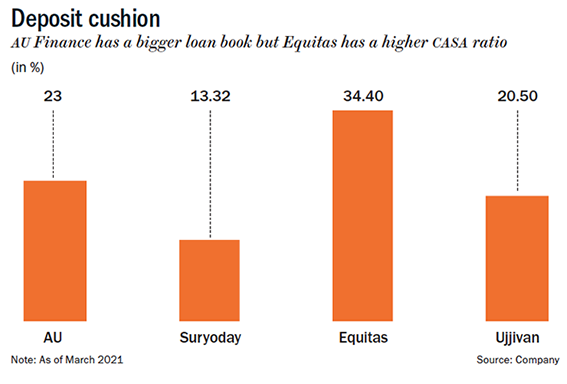

Currently, CASA ratio for the listed SMBs is in the range of 13% to 34% (See: Deposit cushion) and Equitas SFB, as one of the first to transform into a bank in September 2016, had the first-mover advantage with deposit mobilisation. For others, the journey will be longer. According to MicroSave Consulting estimates, it will take at least five to seven years for an SFB to increase its number of clients and average deposit to a level where the cost of deposit mobilisation reduces to become a low-cost, sustainable source of fund for SFBs. Currently, the burden that guidelines place on these banks — capital adequacy ratio (CAR) of 15%, cash reserve ratio (CRR) of 4%, and statutory liquidity ratio (SLR) of 22% — is significant.

Currently, CASA ratio for the listed SMBs is in the range of 13% to 34% (See: Deposit cushion) and Equitas SFB, as one of the first to transform into a bank in September 2016, had the first-mover advantage with deposit mobilisation. For others, the journey will be longer. According to MicroSave Consulting estimates, it will take at least five to seven years for an SFB to increase its number of clients and average deposit to a level where the cost of deposit mobilisation reduces to become a low-cost, sustainable source of fund for SFBs. Currently, the burden that guidelines place on these banks — capital adequacy ratio (CAR) of 15%, cash reserve ratio (CRR) of 4%, and statutory liquidity ratio (SLR) of 22% — is significant.

The cost of transitioning into SFB, from an NBFC, is high for other reasons too. For instance, in the case of AU SFB, the cost-to-income ratio increased from 38% in FY16 when it was an NBFC to 56% in FY20 owing to investment in branches, CRR/SLR drag and technology upgradation, states Sonal Gandhi, analyst, Nirmal Bang Securities, in her report. Around 60% of the costs are fixed while 40% are variable.

ESAF’s Thomas, too, agrees there is an increase in compliance cost, “Cost to income ratio is currently 60%, while as an NBFC it was 45-50%. But, this is a long-term game. I am willing to take the short-term pain,” he says.

Thomas’ grit aside, the interest in SFB licence has waned. According to an RBI list released on April 15, only four applicants have sought the licences — VSoft Technologies, Calicut City Service Co-operative Bank, Akhil Kumar Gupta and Dvara Kshetriya Gramin Financial Services. With SFBs, the minimum paid-up voting capital/net worth should be Rs. 2 billion, while it is Rs. 1 billion for an urban co-operative bank converting into SFB, with the condition that it has to touch Rs. 2 billion in five years.

Another reason for fewer people lining up for SFB licences could also be that NBFC MFIs (the very avatar that the small banks had shed) are now starting to look more appealing to equity investors.

With more MFIs turning into banks, the remaining MFIs now get a larger share of priority-sector lending funds (a credit cookie jar that only few sectors specified by the RBI get to dip their hand into). “That eased the funding pressure,” says Sanjay Kumar Agarwal, senior director, Care Ratings, “Also, post 2016, we have seen more impact funds getting active in the microfinance space and more NBFC MFIs going public.” The sector’s average gearing of about 6X has now come down to 3x, he says.

Meanwhile, SFBs are working to get their loan books in order. They are looking to diversify their liability profile, or a change in the asset mix, away from unsecured lending. In fact, this ranks high in their growth strategy.

Changing the mix

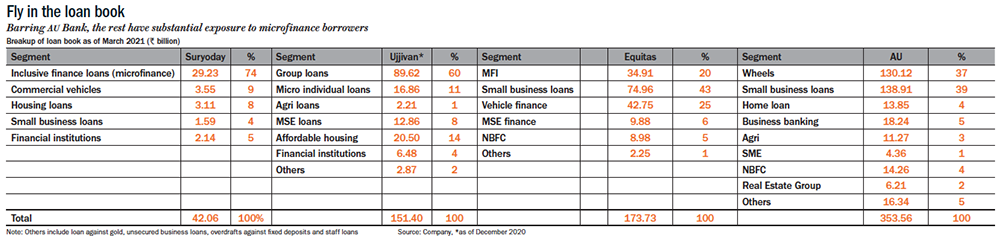

While all four listed MFIs have managed a diversified product mix — across vehicle finance, small business loans and other loan products — only AU is free from an MFI exposure (See: Fly in the loan book). After transforming into a bank, it has moved away from microfinance and vehicle finance to small business loans, MSE, corporate lending, housing finance and others. “The diversity in asset mix helped curtail the impact on collections post demonetisation and subsequent political issues faced by microfinance players in some geographies, as well as COVID-19,” reports Crisil.

While all four listed MFIs have managed a diversified product mix — across vehicle finance, small business loans and other loan products — only AU is free from an MFI exposure (See: Fly in the loan book). After transforming into a bank, it has moved away from microfinance and vehicle finance to small business loans, MSE, corporate lending, housing finance and others. “The diversity in asset mix helped curtail the impact on collections post demonetisation and subsequent political issues faced by microfinance players in some geographies, as well as COVID-19,” reports Crisil.

Players such as Ujjivan and ESAF are on a similar path. “While we will not move away from social lending, our long-term target is to bring down the MFI book to 50% from 85% as we look at other categories such as gold loans, affordable housing,” says Thomas.

Nitin Chugh, CEO, Ujjivan SFB, says, “We are looking to bring down microfinance to 50% of our portfolio in the next three to four years and the balance will be new businesses such as affordable housing and business loans.” Ujjivan’s average ticket size of an MFI loan is Rs. 40,000, while its MSE and affordable housing loans are around Rs. 1.4 million to Rs. 1.5 million each. With its Rs. 39 billion loan book Suryoday, too, has managed to bring its unsecured lending down to 74.59% in Q3FY21, from 95% in FY18.

AU has also launched its housing finance business after becoming a bank in 2017. Since 2018, the bank has managed to diversify away from vehicle and SME loans, which used to be 82% of its AUM and in FY21 is 76% of its AUM. “The management aims to expand into new segments of housing loans, gold loans and consumer durable financing,” says Aggarwal of MOFS.

While this transition was underway, the second-wave iceberg hit, and since then, the focus of SFBs has been to keep the ship steady.

Covid blues

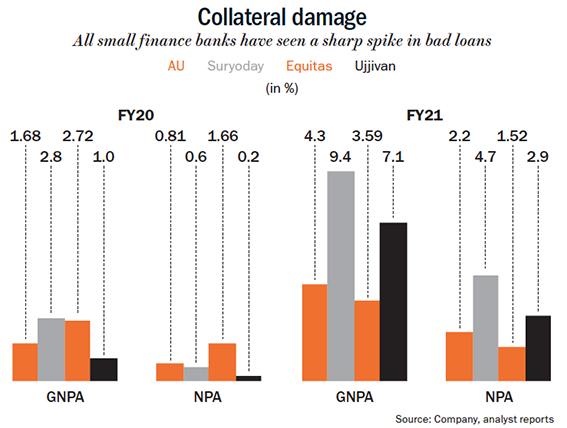

For SFBs, who had just been taking their baby steps into banking, FY21 has been catastrophic. The four small banks reported their highest-ever gross and net NPA numbers for the fiscal (See: Collateral damage). While AU has reported gross NPA of Rs. 15 billion (4.3%) and net NPA of 2.2%, Equitas has seen GNPA and net NPA of 3.59% and 1.52%. PN Vasudevan, MD and CEO of Equitas, played it safe in the Q4 earnings call by stating, “With the fresh lockdowns and restrictions being announced across various parts of the country, what impact it will have on our customer segment guidance for the current year looks quite difficult to make at this point in time.” During the quarter, Equitas had to write-off Rs. 1.71 billion in the MFI portfolio, and it has provisioned Rs. 3.75 billion in FY21 against Rs. 2.47 billion in FY20. Ujjivan reported GNPA at 7.1% and NNPA at 2.9% in FY21 even as it wrote-off Rs. 740 million in Q4FY21, while Suryoday saw its GNPA surge to 9.4% (Rs. 3.93 billion) even as it wrote off Rs. 969 million during the fiscal compared to Rs. 634 million in FY20. Net NPA was 4.7% compared with 0.6% in FY20.  As for AU, though it does not have MFI exposure, the bank restructured loans of Rs. 6.41 billion (1.8% of advances) in Q4FY21 against Rs. 2.51 billion in Q3FY21 (0.8% of advances). Nearly 90% of the restructured book was from the wheels and small business loans segment, which is a lucrative business in other times. The management in the earnings call indicated that the cab-aggregators’ segment will remain under pressure, with business weak under lockdowns and restrictions across geographies.

As for AU, though it does not have MFI exposure, the bank restructured loans of Rs. 6.41 billion (1.8% of advances) in Q4FY21 against Rs. 2.51 billion in Q3FY21 (0.8% of advances). Nearly 90% of the restructured book was from the wheels and small business loans segment, which is a lucrative business in other times. The management in the earnings call indicated that the cab-aggregators’ segment will remain under pressure, with business weak under lockdowns and restrictions across geographies.

Chugh of Ujjivan SFB, believes the business environment has become too unpredictable. “We don’t have a ready playbook for this unique situation. We had upfronted our provisions in Q3, but we did not know then that we will have a second wave of this kind.” For now, it is amply clear that SFBs will need to recalibrate their growth projections and set their house in order before chasing growth. “There are enough opportunities, but for now, we are just trying to focus on the basics,” he says. The same note of caution came from Rohit Phadke, president and head of retail assets at Equitas, when he told analysts in the Q4 earnings call, “It is too early to give guidance on what will happen because of COVID restrictions.” Not surprising then, analysts are pruning growth and earnings estimates.

Living in uncertain times

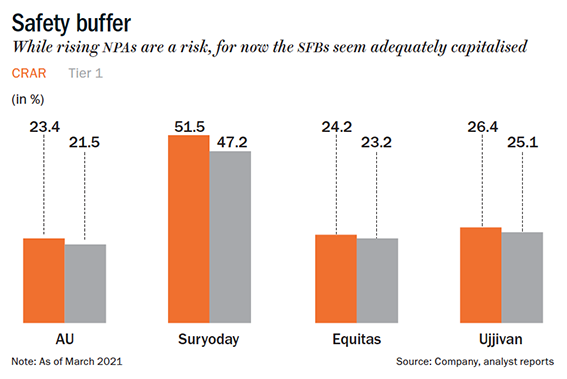

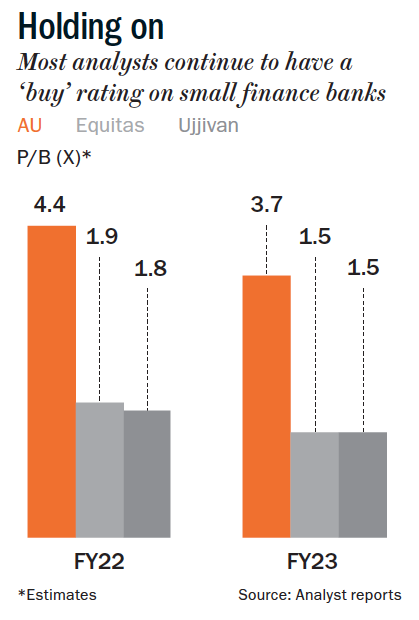

While the SFBs are looking at growing threat of delinquencies, the situation isn’t dire yet. Thankfully, all four banks have adequate capital (See: Safety buffer). Though the top 10 SFBs today account for just 1% of total lending and 0.5% of the entire deposits in the country, they are still rated favourably by analysts because of their comparatively stronger profitability and return ratios (See: Holding on). For instance, Aggarwal of MOFS, points out that AU’s valuation is not expensive, “The stock has already corrected 30% from its high and, compared to public and private sector banks, its return ratios are in higher double digits.”

AU’s net worth crossed Rs. 60 billion, aided by equity infusion of Rs. 62.5 million from a QIP in March 2021. Its capital adequacy ratio stood at 23.4 and Tier-I capital was 21.5%. “We expect the management’s near-term focus to be on strengthening the balance sheet and improving its coverage ratio,” says Aggarwal of MOFS. AU’s collection efficiency and customer activation rate have moved higher than pre-COVID levels, with 81% of loans at zero days past due, similar to FY20. Agarwal has a ‘buy’ on the stock, even as he cut FY22 and FY23 earnings by 20% and 17%, to factor in higher credit cost. “AU has enough capital buffer. While profitability will remain lower because of higher provisioning, it won’t burn capital for growth,” says Agarwal. MOFS has a ‘buy’ on the stock at 4.4x and 3.7x FY23 price-to-book.

AU’s net worth crossed Rs. 60 billion, aided by equity infusion of Rs. 62.5 million from a QIP in March 2021. Its capital adequacy ratio stood at 23.4 and Tier-I capital was 21.5%. “We expect the management’s near-term focus to be on strengthening the balance sheet and improving its coverage ratio,” says Aggarwal of MOFS. AU’s collection efficiency and customer activation rate have moved higher than pre-COVID levels, with 81% of loans at zero days past due, similar to FY20. Agarwal has a ‘buy’ on the stock, even as he cut FY22 and FY23 earnings by 20% and 17%, to factor in higher credit cost. “AU has enough capital buffer. While profitability will remain lower because of higher provisioning, it won’t burn capital for growth,” says Agarwal. MOFS has a ‘buy’ on the stock at 4.4x and 3.7x FY23 price-to-book.

Even Suryoday, whose net profit fell 89% year-on-year to Rs. 119 million in FY21, enjoys a CRAR of 51.5% because the bank raised Rs. 5.81 billion through its IPO in March.

Dnyanada Vaidya, analyst, Axis Securities is also bullish on Equitas and Ujjivan. “The improvement in Equitas’ collection efficiency, which is inching towards pre-COVID levels across segments, is encouraging. The stress in the MFI space, despite a Rs. 1.71-billion write-off, remains a cause of concern. However, we remain confident of the bank’s ability to tackle this stress,” states Vaidya, who has a ‘buy’ on Equitas at 1.9x FY23 ABV with target price of Rs. 70, implying an upside of 11% from the current price.

She also has faith in Ujjivan’s business model. “While COVID 2.0 is likely to delay the recovery process, we are confident in the resilience of the business model,” mentions Vaidya in her report, valuing Ujjivan at 1.8x FY23 ABV with target price of Rs. 37/share, compared to the current price of Rs. 29.

She also has faith in Ujjivan’s business model. “While COVID 2.0 is likely to delay the recovery process, we are confident in the resilience of the business model,” mentions Vaidya in her report, valuing Ujjivan at 1.8x FY23 ABV with target price of Rs. 37/share, compared to the current price of Rs. 29.

Chugh of Ujjivan SFB believes he has the backing of patient investors. “All the investors realised that we are a three-year-old bank, and that it’s a long-term story that will play out over next three to five years or even more.” Thomas, too, believes that investors and depositors alike will be sympathetic. “It’s how you tell the story. In the south, ESAF is known to help small borrowers and to engage often in social development. When we go to newer markets, we tell people that, along with financial return, we also give them a social return. That the money they deposit with us will help a family find livelihood or a father to keep his daughter in school,” he says.

Will the investors go with the heartwarming story or the hard numbers? While the SFBs find themselves in a tough spot, their capital buffer should keep them going for a while. The trouble will truly start only if the economy does not recover soon.