When Azim Premji decided to start a philanthropic foundation back in 1999, it was not the result of any a-ha moment. The intention to give back to society was fixed in his mind as a child, seeing his father’s upright actions and the dedication with which his doctor mother ran a children’s charitable hospital. Premji would have chosen to work for an international development organisation but for his father’s untimely death in 1967, following which he dropped out of Stanford to manage the family business. If his transformation of his father’s vegetable oil company into a software services behemoth is the stuff legends are made of, his philanthropy is just as noteworthy. Premji has committed $5 billion of his personal wealth to the Azim Premji Foundation and last year became the first Indian to sign the Giving Pledge, committing the bulk of his wealth to philanthropy. In this interview, Premji explains why giving is all about having the right mindset.

Tell us about the influence your mother had on you, and the values that were instilled in you in your growing years. Can you share some anecdotes?

Both my mother and father have influenced me significantly in their own ways. My mother was a qualified doctor and must have been one of the earliest Muslim woman doctors. She set up the Children’s Orthopedic Hospital at Haji Ali in Mumbai in the 1950s. It was a completely charitable hospital. Running it was very hard, both to operate and raise funds, and I saw my mother completely dedicated to it. I think that has played a role in my orientation towards social issues.

I remember once, at some incitement from outside, some of the workers at the hospital went on a strike demanding higher wages. My mother ran the hospital on donations and it had no ability to offer a raise. They were sitting on strike at the entrance of the hospital. My mother got a large number of white sheets and hung them around the workers so no one could see them and the hospital went about its work. By evening, the striking workers were tired of sitting and not being noticed, and went back to work. I remember this quite vividly. Nothing would stop her work for the children; her dedication was extraordinary.

My father had his business and along with that, he was also the honorary chairperson for the Electricity Board. One day, a successful businessman came to meet him, asking for an out-of-turn electricity connection. My father politely communicated his inability to break any norms. After the man left, we discovered a briefcase full of cash — sounds straight out of a film, but that’s the way it happened. My father was livid. He walked straight to the nearest police station. His uprightness and directness, in hindsight, certainly affected me.

My father had his business and along with that, he was also the honorary chairperson for the Electricity Board. One day, a successful businessman came to meet him, asking for an out-of-turn electricity connection. My father politely communicated his inability to break any norms. After the man left, we discovered a briefcase full of cash — sounds straight out of a film, but that’s the way it happened. My father was livid. He walked straight to the nearest police station. His uprightness and directness, in hindsight, certainly affected me.

I must also add that the time in which I grew up has had a big influence on me. It was really the time of idealism in public life. We were building the nation and we all knew that. All of us grew up believing that contributing to nation building was our basic responsibility.

You have said in an earlier interview that the reason why North America leads the way in philanthropy is because of how families are structured. In India, the ties are stronger than in the US and that could be the reason it’s more natural for Americans to think of philanthropy. Do you see things changing in India going forward?

These are not easy things to comment on definitively. There has been no conclusive research on these matters. I can only hypothesise based on my experience. There are many differences between India and the US. Many of these have deep socio-cultural roots.

For example, giving to religious causes, giving to specific community causes, the impact of having large joint families holding the wealth, etc, are rooted in socio-cultural causes. We have to understand that nations will be different on philanthropy or, at least, will follow different trajectories.

There are some other reasons for these differences: the tax structures — estate tax in particular — in the US are one kind of consideration. One must not start believing that tax structures can drive philanthropy. They are a kind of influence. Also, the fact that Indian businesses and businessmen are at a certain stage in the cycle of wealth creation... In fact, why look only at differences between the US and India? There are differences in India across socio-cultural regions. As one example, southwestern Rajasthan has a deep culture of philanthropy. People from there have moved to Mumbai, Ahmedabad and other cities to create wealth, and they support various causes in their hometowns and villages. The depth of this is quite amazing.

I am very hopeful that philanthropy will increase by leaps and bounds in India over the next two decades. We can see signs of it already — many people who became wealthy after the 1980s have been doing quite a bit. That’s in addition to groups like the Tatas, who have contributed immensely in the past 70-80 years.

Is giving really a function of the amount of wealth? Or would you think it’s a mindset issue? What has been the greater motivator for you?

At its core, it’s a mindset issue. No amount of wealth may seem sufficient to support philanthropy and on the other hand, no amount of wealth is so small that it cannot support some philanthropy. But this “mindset” must come from within. I have always felt that I am the trustee of my wealth, not its owner. And so, the wealth must eventually go towards real social causes.

Would you agree with the assessment that in India, empathy levels usually go down when you rise up the power/wealth ladder?

I don’t think that empathy levels go down as you go up the power/wealth ladder. It’s possible that since people have less opportunity for engagement with the issues of the disadvantaged as they go up that ladder, they may not be able to appreciate all its nuances and complexities. Empathy is a basic human character; some people have more of it and some less. And in my experience, that doesn’t necessarily correlate to where you are on that ladder. I don’t see such a bleak picture in our country. We can and we must do more. But, as I said before, I see good signs and I am very hopeful.

When you are wealthy, how do you ensure that your children do not grow up with a sense of entitlement?

There is really no complex formula for this; it’s basic common sense. Behave with your children as though they are living in an average middle class (perhaps upper middle class) home. They will go to similar schools, commute as their friends, play in the same places as them, wear the same things and not get a Porsche as a birthday gift. They also have to see that you treat yourself with the same standards. What is complex is that it has to come from within you. You have to conquer yourself. I must also add — and not everyone would agree with me on this — that one can also clearly convey to children as they grow up that this wealth is not theirs or ours, but that we are holding it in trust. Your actions will have to support this stance in the form of a demonstrated responsibility with which you use the wealth.

Can you tell us some powerful things to tell your children and grandchildren to make them more empathetic to society, and understand the importance of equity?

“Telling” doesn’t really work well. I would suggest immersing children in the reality of what most disadvantaged people in our country deal with everyday. Not some whistle-stop tour of a slum, but genuine continuous engagement with some social issue or cause.

You have acknowledged in the past that philanthropic work is different from business and one has to change one’s mindset significantly to make a difference. Can you take us through your journey of learning in philanthropy?

I will use my favourite analogy to explain this. If you are a good football player, and want to start playing cricket; the speed, stamina and fitness from football will help you. But you cannot insist that you will play cricket with the rules of football. It will be a disaster. This is the kind of change one has to make from business to the social sector.

One needs a completely different level of patience on social issues. Things change very slowly. They can often unwind and one won’t even know why. And so one has to go back and try again — tenacity is critical. Social issues are interrelated in complex and intricate ways. It’s difficult to isolate specific issues and causes that are plaguing our country. One has to take a holistic approach and remain committed for the very long term.

Anurag Behar tells us that you have given the Azim Premji Foundation significant autonomy, and do not question its decisions. How can you trust a team of professionals with $5 billion and not ask questions?

I think this is quite simple. It’s actually the reverse of what your question suggests. It’s precisely because we are talking about reasonably large sums of money that the foundation has autonomy. The only way to use that size of money effectively is to have a good organisation. One cannot build a good organisation without giving it autonomy. In fact, if I had given all that money and the organisation didn’t have autonomy, it would be a self-defeating exercise.

I think this is quite simple. It’s actually the reverse of what your question suggests. It’s precisely because we are talking about reasonably large sums of money that the foundation has autonomy. The only way to use that size of money effectively is to have a good organisation. One cannot build a good organisation without giving it autonomy. In fact, if I had given all that money and the organisation didn’t have autonomy, it would be a self-defeating exercise.

Like any large organisation (and we are one by now), we have a fairly clear set of processes of strategy formulation, review etc., and we follow that. I play a role in that, but make sure I don’t impinge on the autonomy — I like to remain engaged, but not interfere. I like to travel and see the fieldwork for myself; the sense that you can get by being there cannot be substituted.

Eventually, what we are trying for is to be able to contribute to a better India through better school education. That is our purpose. “Better” to me means just, equitable, humane and sustainable — an India as envisioned while writing our Constitution.

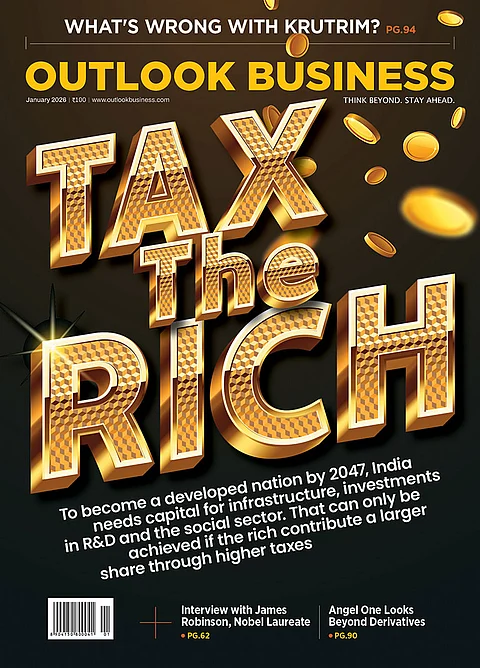

Andrew Carnegie recommended high wealth tax in his Gospel of Wealth. In recent times, William Gates Sr. and Warren Buffett have publicly supported taxing the rich. You share their sentiment. We have had high wealth tax in the past in India. Do you think it was a good idea at that time? Will it be a good idea now?

The devil is in the detail here, so there can’t be a simple answer. There are too many issues related to taxes in India. For example, broadening the tax base and the issue of unaccounted wealth. In the context of our discussion, I have to say that taxation can’t be a substitute for philanthropy. We must increase our philanthropic efforts. I feel that the wealthy have a responsibility towards society beyond taxes.