It was 1988. I was at a Sunday lunch at Sudhir Merchant’s house when solicitor RA Shah casually mentioned that Australian MNC Nicholas Laboratories wanted to sell its operation in India. Right there, I made up my mind. On Monday, my bid reached the Nicholas group.

I knew nothing about the pharma business, just that the family once had a drug store. Kemps Corner not only housed a retail store but also a pharma business, which Dad had bought from Kemp & Company. Eventually, we had to shut it down because we couldn’t run it successfully but we kept the retail space. I didn’t realise it then, but pharma needs manpower for promotions and sales. You need medical representatives to go and call on doctors. Even if you have a Rs.20 crore turnover, you need 100 people. In textiles, you can make Rs.100 crore with just five people.

The Nicholas acquisition was pure serendipity. There were several others in the game — some who bid more than us; an investor who owned 10% in the company and had served on the Nicholas board; the top management, who had the backing of a financier to take over. We really stood no chance but ended up inking the deal! Of course, Nicholas had initially signed the deal with Reckitt & Colman. The latter backed out after they realised Nicholas had certain contingent liabilities on account of an excise duty dispute. We did an estimate, got the lawyers in, who said it was unlikely the liability would materialise.

When you are putting in money as an entrepreneur, you look at the pay-off and take the risk. As a professional manager, you worry about a hundred things. I remember the meeting with Mike Barker, who was responsible for making this deal happen. I told him that all I have is a dream, an impossible dream to make Nicholas among the top five pharma companies in India. It was ranked 48th at that time. I don’t know why I said something so audacious. I don’t know if Barker got impressed by my ambition or my sincerity, but he did. We shook hands.

Years later, I and Swati met Barker in Kenya. He was in his seventies. He had retired. When we showed him the balance sheet, highlighting how Nicholas was now one of the leading pharmaceutical companies in India, he was delighted!

***

It was probably the toughest deal I ever did, not just because it was my first big one. Those were the days of Licence Raj. The Controller of Capital Issues (CCI) had to approve the deal price. I had asked the CCI to price the deal higher than others. The rest were peeved — some rivals were pitching for a lower price, with a view to settle some portion in overseas accounts. The company management professionals, who also bid, complained to some government officials. Former finance minister Madhu Dandavate raised the question in Parliament! It was sheer luck that Dandavate was an old family friend. He and my uncle were in jail together during the freedom struggle. When I went to meet him, he didn’t recognise me. Our family name was Makhariya. But my father used my grandfather’s name, Piramal, as his surname, and we continued the tradition. Once I explained all that to him, he heard me out. The deal went through… Nicholas was ours for Rs.16 crore.

The first thing I did when I got into the driver’s seat was to dislodge the management. I was naturally upset. How could I work with people who had connived against me? There was no trust there. I fired them! I had an unfamiliar business in hand and no one competent or trustworthy to guide and steer it. In that first board meeting though, I re-iterated what I had told Barker when I pitched for the deal: “This is 1988. By 2000, we should move from No. 48 to the top five.”

At that time, Swati was already getting her public health degree from Harvard. Back in India, I was managing the business and Nandini and Anand’s homework! They were 11 and 7 years old. I was 36. I wanted to sharpen my skills and understand the world better too. So I signed up for the Advanced Management Programme at Harvard Business School. I shifted to Boston with the kids, dividing my time between the hostel and our apartment. It was the best time we had as a family. Our favourite destination was the science museum in Boston! Later, Anand would also go to Harvard Business School… he always wanted to because of his childhood memories.

My eyes and ears were always open to acquisitions, so we could grow in rank. Roche was the next big deal that came our way. They had an old vitamin-A bulk drug manufacturing plant in Thane, which was giving them stress. An explosion in Shree Ram Chemicals factory in Delhi had created an uproar. The Supreme Court had come down heavily on the company, pinning down a lot of responsibility and liability. Roche was worried about operating the old plant.

I sensed an opportunity. We were on a great wicket thanks to Nicholas. But it had come at a huge cost. Nicholas only had an old plant in Deonar. We put up a brand new plant in Pithampur, which cost as much as the company’s turnover at the time. Everyone dissuaded me from pursuing Roche, but I was clear. I didn’t want to take any other route. What also helped was that Nicholas had some business in Europe, which Roche had acquired, so they already had some exposure to us.

No matter how sincere your efforts though, the competition will never let go of things easily. During the Roche deal, the pressure was intense. The first presentation I made to them got destroyed in a fire! Those days, we only had prints, no backups. It was painful. The competition was on our heels. One of them said, “Both of us want this so we’ll only end up raising the price. Let’s simply toss a coin and whoever wins can have the deal.” I was categorical in my denial, I didn’t want to toss a coin and leave it to luck. Then came the threat, “My family’s well connected in Switzerland. I’ll speak to someone on the board and we’ll have the deal anyway (so why jack up the price unnecessarily)?” I didn’t pay heed to any of this. There was no way I would toss that coin.

I flew down to Basel. I had given a free hand to Chandru Hattangadi, who along with Swati, had made an elaborate presentation. Roche held the largest number of patents globally. In India, they had a presence but no patents. Importantly, they didn’t want to spend more in India. We, on the other hand, had money to spend on growth.

We thought they understood us. Till the evening, when we met for cocktails, everything sounded great. The next morning, when we saw their presentation, we were left distraught. It was completely one sided! They wanted us to invest in their plant, products, add people on the field and grow. Essentially, they wanted us to buy the company at a good price, spend more money to get it to their level and then give them control through six-monthly inspections!

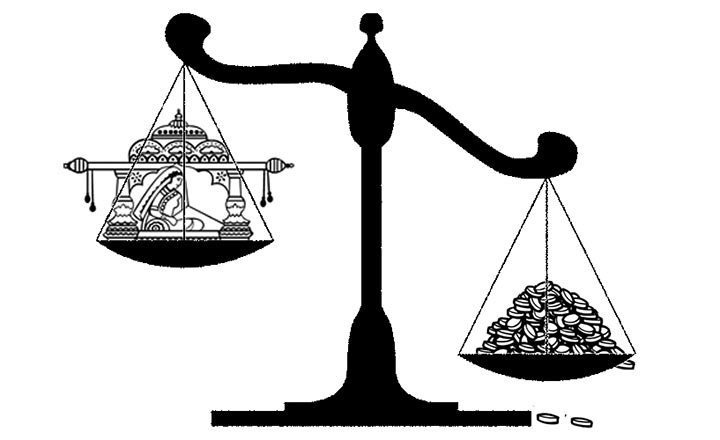

Chandru came back in the evening with some scribbles. We were meeting again for dinner. He described the demands as dowry. But dowry for what? For an old plant? For products that showed no growth? His note said: “Roche is one of the largest holders of patents globally, is well known, and is looking for a partner in India to accelerate growth by rolling out new patented products in the country. The partner must be committed, come with all the required financial resources to make a new beginning, and they’ll want to inspect and review the partner’s performance every six months.” It was like putting a chastity belt on a partner! The right to come calling and inspect every six months if there were violations!

Nicholas only had two conditions attached to the deal. One, that the quality won’t be compromised. Second, we don’t export using their brand name. This was because the cost of manufacturing was so low in India that it would end up burning their markets. I wondered for a few minutes if Roche’s demands were a bit too harsh or we were being too harsh in bracketing it as dowry demands. Eventually, I decided to hand them the note anyway. We had nothing to lose. The next morning, the mood was different. They said let’s talk pricing!

We got the brands, real estate, everything for Rs.20 crore – it was almost free. I had gone with a lot of preparation, willing to pay. There, I found out that they were expecting a certain price after tax. They were, in fact, budgeting for a huge tax payout. My calculations showed there was absolutely no tax liability. I told them there was no need to argue over tax implications. I’ll simply pay the post-tax price they were expecting. We had a deal. It was 40% lower because I had got my math on the tax liability right! I paid a deposit then and there, and signed the deal.

But as it turned out, Roche was still in touch with a competitor. They probably wanted to keep an exit window. Our friend got carried away, thinking the deal was going to be his. The day Roche broke the news they had inked the deal with me, he was an unhappy man. Again, what swung the deal in our favour was how we put the proposal across – like a marriage. In between the talks, visits to our plant in Pithampur and our credibility made a huge difference.

Then on, almost all multinational pharma deals came to our table first – Boehringer Mannheim, Rhone-Poulenc, ICI, the list goes on. When it comes to deals, it is important to put yourself in the shoes of the counter-party and see what they care for. Then, figure out solutions around that. We were never the highest bidder for any acquisition. We still landed deals because we had a keen sense of what the seller wanted and could meet that expectation.

Boehringer was a similar story. In 1996, two patients died in an eye camp after consuming a defective batch of Comsat Forte, an antibiotic manufactured by Boehringer. The company’s MD Paul Stinson and other senior officials were so scared that they fled the country. Boehringer was a private company, owned by one of the richest families in Germany. They didn’t want their reputation tarnished. The Asia Pacific head Dieter Dormann, was overseeing the operations of India. I told him let’s see how we can resolve the issue. They were more than happy to sell. As it turned out, they not only sold us the entire company, with the brands and real estate, but also paid Rs.100 crore so we could settle the potential liabilities! When we got that money in our forex account, an amused Reserve Bank of India asked: “Are you buying a company or selling?”

With the Rhone Poulenc deal, too, the bankers involved in the transaction favoured a competitor. They tried to ward us off by extending the bid time. I called up a friend in Germany and got my point across to the management. The deal was ours. The ICI transaction was just iconic, the speed of that execution! CFO Mahesh Gupta had just joined and within a week, we closed the deal. He was stunned. He had never seen a deal happen that quickly. The mistake people often make is they don’t take decisions, keep vacillating.

Those were the days I met the late Sumantra Ghoshal. I was on the lookout for someone whose opinion I could rely on. Someone who was not a banker! He was smart. I don’t know how he figured out the tension between us. I was always guarded with him because he was also consulting with Ranbaxy. He then asked me to meet Nitin Nohria, who was like his disciple. The Rhone-Poulenc deal was on my mind those days. I asked for his opinion. He suggested a price far higher than I had thought. I was impressed by his logic – he had built in the benefits of integration! He burst the myth that mergers and acquisitions don’t work.

Later, when he was offered the position as the dean of Harvard Business School, he simply told them he’ll continue his association with us. As the dean of Harvard, you can be on the best boards in the world, but he stuck with us. That only strengthened the bond. Whether it is people or horses, once I am attached to something, the relationship, from my end, only grows.

One of the high points of my early life was horse riding. Mother took me to the riding club, which used to be near Shiv Sagar Estate (now Ceejay House). I grew so fond of riding that I started following father everywhere around the house, asking for a horse! I told him it wouldn’t cost him much but he never budged. He was concerned that I would take to racing and gambling at a critical age. Years later, he would gift me one. Like a good grandfather, I have four for the family at the Amateur Riders’ Club.

This is the second of a three-part series. You can read part one here.