- Best days of my life Two years at IIM, I enjoyed every day

- Sounding board Papa, Alka, cousins Aditya & Uday

- Most touching moment The Sunday early morning ride on Marine Drive with papa, mama and Alka. It was an incredibly emotional moment... I used to say as a little kid that one day I’ll buy a Mercedes and drive around with papa and mama in the back seat... The various rituals Alka and mama did when I was battling the Cadbury crisis - Saturday poojas, cow feeding and what not

- Lowest point When Alka lost her parents within two days of each other. It showed a cosmic link, but also, how abruptly life could end

- Sheer love Alka, PG Wodehouse, 70’s Kishore Kumar, Chupke Chupke, Golmaal, 3 Idiots, kebabs, mountains, sports, Macallan 18

- My idea of life Zindagi Ek Safar Hai Suhana

- Inspiration Umar bhar Ghalib yahi bhool karta raha, Dhool chehre pe thi, aur aina saaf karta raha

- Most-prized possession My box of letters, photos, little gifts. The best of all, the note by Alka, Abhay and Meghana on my work - it’s been on my desk forever

- Best gift I ever got On my 50th birthday, Alka compiled a book where everyone, from parents to colleagues to friends, wrote a page on me

***

My grandparents were keen that I stay at home when it came to college. I guess having been away from the family in boarding school since I was seven, they wanted me close by at least now. With Papa getting posted to a new place every three years, my parents had sent me to Lawrence School, Sanawar, to ensure I got a steady education — but when you’re still in short pants and used to your mama holding your chin to comb your hair, all that registers is that you were being left alone in this unfamiliar place, not the thought behind the deed. But now, I was glad I had been in boarding school, for not only had it taught me to cope when I was away from home but also the value of home itself. And staying with my grandparents gave me the best of both worlds — the palatial home in Chandigarh where papaji and maaji pampered me, while chacha would sneak me in through the back door when I returned home late. Papaji would keep wondering when I studied, since he slept early: “Padhe bina itne achche number aate hai, to padh ke kitna achcha kar sakte ho.” But I was enjoying my freedom too much to listen to him — parties, playing tennis and hanging out with my friends.

Papa had cut a not so good deal — he had persuaded me to study science in school, hoping I would be inspired to look at engineering thereafter. But I had agreed only on the condition that I would be free to choose my subjects after school. How his face fell when I told him I wanted to study humanities — “Baba, it’s not for serious students.” Finally, we settled on commerce in college and I don’t know if I was lucky or the others were unlucky but I made it to IIM Ahmedabad. The two years at IIM were wonderful and, before I knew it, it was time to graduate. That was 1982.

Back then, Labdhi [Bhandari] Sir was almost like a god to us and when he said Asian Paints was a great company for me to work, I went in happily. Mama wasn’t so convinced when she came to Agra to help me settle down at my first posting. “Baba, exactly what do you do?” she asked, almost naïvely. I earnestly explained to her how I visited dealers and pushed them to stock Asian Paints. “Yeh to phir salesman ka kaam karte ho, na? Agar yeh hi karna hai, toh MBA ka kya fayda hua?” There I was, patting myself on the back for landing a much sought-after job straight from campus and in five seconds, I was back to Mother Earth. Even my posting in Western Uttar Pradesh — not too surprisingly — didn’t excite her too much!

UP was a different world. Of the 12 districts allotted to me, eight were dacoit-infested, which meant the state did not guarantee your safety. My first visit to Mainpuri was an eye opener. Sharadbabu had two rifles displayed prominently above the counter at his shop. When I asked him why there were firearms in a paint store, he replied, “Yahan kabhi kabhi goli chal jaati hai. Aapke hote hue goli chal jaye, to aap counter ke peeche aa jaana.” He would give me the other rifle, he added; after all, the son of a military man would know how to shoot.

In the early eighties, small towns such as Mainpuri typically had a main street with one store each for various things — one grocer, one utensils seller, perhaps a couple of clothing stores… But there were a number of jewellers here. Sharadbabu explained why: “Dacoity ka maal kahin toh bikega, na.”

This was the real India! And for three years, this was what I was exposed to, 24/7. Every dealer activity in UP would bring fresh excitement. At one painter meet, a rival dealer’s team landed up with their laithet (goons). Our organiser was unconcerned — “Aap bolo to hum apne laithet bulwalein?” Was I supposed to sell paints or watch laithets slug it out? Still, the ability to connect with the roots to understand how the system really works is perhaps the most important requirement for a marketing guy. I learnt about the environment, the market and made enduring relationships with dealers — many years and many kilos later, we are still so connected.

There were no distractions from work and my first boss, Verghese Anthony, was a blessing. Very systematic, very patient. I spent my first three months — uninterrupted — with him. I was single, he was quasi single as his wife had gone home for delivery and we focused singularly on work. Not many people are lucky enough to get that kind of mentorship. Verghese was very particular about how he did everything. Even parking his car — not two feet left but right on the spot. If there was another car jutting out, his horn would blare and security would be summoned to ask the owner of the offending car to move it by 12 inches! Getting started at work was also a ritual. Place the briefcase on the table, click it open — one flap was torn so the visiting cards would fall out, which would be put back in place — and then take out all the paraphernalia, pen, diary, small note pad, one by one. Verghese was so meticulous: every envelope had to be cut with a small pair of scissors at precisely 0.3 cm margin; after the letter was pulled out, he would gently press the envelope on the sides and peep into it to double check that it was indeed empty.

Each boss teaches you something — Verghese taught me early on the value of just following through. I was a brash boy raring to go and he was the experienced branch manager whose middle name was patience. He gave me time — while taking away mine — and that gave me a completely different perspective and lots of learning.

***

From UP, I landed in Bombay as branch head. Suddenly from the rural markets of UP, I was in charge of the company’s largest branch.

Our big boss, Mr Abraham, was an Asian Paints legend, having been in sales and marketing for 20 years. He had an elephantine memory; he forgot nothing. Let me say that again — nothing. If he told you to come back with some assignment on a particular day, no prize for guessing who was on the other side when the phone rang at 9.30 in the morning. “Bharat… Can we meet?” I was not just awestruck but crazily curious on how he managed this. So, I asked him. In his inimitable style, Mr Abraham explained: “I have these different notebooks for different things. At the end of the day, I look at all the jottings of the notebooks and mark them in my diary on that particular date. Every morning at 5 am, I check the diary for the day’s tasks. And until I tick off all the items on the day’s list, I don’t leave for home.” Unsurprisingly, Abraham would be very upset if you were not ready with what you had to deliver on the appointed date — he was perfectly okay if you called in advance and told him you were not ready and set another date for the discussion. Looking at Abraham, I used to often think the phrase should have been “Time and Abraham wait for no man.”

One day, he called me in and asked very seriously, “Bharat, what are your plans for marriage?” The question came out of the blue and I looked at him blankly, not knowing what to say. “I keep getting these enquiries about your marriage plans from various people across the industry. What do I tell them?” Finally, I replied. “Sir, you could say he has left it to his parents.” He was delighted to have found a convincing answer. Actually, one of the best things that happened to me at Asian Paints was Alka, who was my first management trainee! Abraham grinned widely when Alka and I went up to him in 1989 and told him we planned to marry. We suggested that one of us would look for another job and move on. He rejected that notion immediately. “No. Both of you are assets to this organisation and both of you should stay.”

I still don’t know what gave me the courage to refuse the factory assignment in 1990 — every high-pot was sent on a factory assignment and refusing that natural progression simply meant stalling your own growth. Sukumar, my immediate boss and Abraham were stunned when I said no, but I was clear I did not want to do a job I did not enjoy. Sukumar told Mr Abraham, “I’ll talk to him and come back to you, Sir.” Next thing, I get a call from Abraham: “Bharat…I understand what you are saying. You do what you think is right!”

My best performing boss was PM Murty! If there had been a Man of the Moment award at Asian Paints, Murty would have won it every single moment. It seemed as if there was no problem he couldn’t handle, instantaneously.

“Sir, Agra has a problem. The dealers are…”

“Bharti, connect me to Sharadbabu in Agra.”

“Sir, they are saying they have already raised this issue with…”

“Meera, call the area sales head for UP.” “Haan, hello…”

Three minutes later, the issue resolved to everyone’s satisfaction, he would turn to me and ask, “What else, Bharat?”

I have been truly blessed as I have had great bosses all through. I can’t forget the clarity Mr [Rajagopala] Chari, one of the institution builders at Asian Paints gave me when Asian Paints was going through that rift back in 1997. There were constant, conflicting messages from the families and I went to Mr Chari for advice. What he said is etched in my memory: “We are professionals. We work for Asian Paints, no one else. So, whatever is good for the company is what we should do.” It was so simple and thereafter there was never any ambiguity in my mind. That’s an important lesson I learnt— when you are pulled in different directions because of multiple power centres, always stick to the ground rule: do what’s in the best interest of the company.

Ultimately, what shapes you as a leader is the sum of all your learning experiences, especially in the initial years. I was lucky to have been with Asian Paints where every single person was extraordinary in some respect or the other. Labdhi Sir was bang on.

***

The best part of the journey was how during that period, Asian Paints transformed from a dealer-push business to a customer-pull business. It was also the time I realized how things could be lost in translation, literally! Raoul da Gama Rose, our creative head at O&M, had made a lovely English creative — “Celebrate with Asian Paints” — but, whoa, the Hindi creative was “Asian Paints ke saath jashn manao”. My heart sank in that meeting — we were looking to expand; literal translations of English lines just wouldn’t cut it. Thankfully, Piyush [Pandey] came along — he was the Hindi copy chief — and he instantly came up with the line, “Har khushi mein rang laye”. I fell in love. It’s been such a lovely and long partnership. That was 1988.

At the heart of Asian Paints’ makeover was a very simple but powerful insight: that people bought shades, not paint. “Mera wala cream” was a smashing hit. Launching 150 shades, then launching Colour World with tinting machines and taking the shades all the way to 1,500, and then the exterior paints — all of it changed the complexion of the paint market. What great thinking by the team!

That’s the time I learnt successful ad campaigns are not really about just having a great creative but packaging a message borne out of a powerful insight.

***

I was happily growing at Asian Paints when a headhunter called to ask if I wanted to head sales and marketing at Cadbury. As in many other cases, I said no. We were at a family dinner with my cousin Aditya [yes, HDFC Bank wala] who asked me, “Do you realize that you may be doing this job for the next twenty years? You are only 36 and the next job — that of the managing director — is held by the family. Had he not put that niggling thought in my head, I may not have actively considered Cadbury.

Some months later (after a set of very emotional farewells) Cadbury happened, I was happy — at least, this product tasted better! Not that I’ve ever tasted paint, I would like to clarify. My first thought was of my sister Shivani. After the IIM-A placements, I’d gone with my batchmates to Shimla where my parents were posted at the time. Shivani had made a face and said, “Bharat, your friends are going to Pond’s, Lakmé, and other such interesting products… and you are joining a paints company. Couldn’t you have joined an interesting product such as chocolate?”

In 1998, when I joined as sales and marketing head, there was a feeling that Dairy Milk was saturated and that we needed to develop new brands. What a colossal mistake it would have been to go with that premise. Meanwhile Geeta and Jasmeet (from Third Eye Communication) narrowed down on something else — grown-ups are not comfortable eating chocolates openly. The same message was coming in from small towns all over India: People said, “It’s not for us older people. It’s a Westernised product, so you can take a little bite from your child quietly but not be seen indulging yourself.” That insight was 50% of the battle won. We needed to legitimise eating of chocolates. The idea was to make chocolates for the masses without losing its class. But how?

“Khaane walon ko khane ka bahana chahiye.” It was incredible how Piyush, Sonal Dabral and Rajiv Menon meshed it in the message. Cyrus Broacha looked just the part: the street vendor who would go around encouraging people to share their reasons —“Iss mein doodh hi doodh chhalakta hai.” And, then, the Rs 5 price tag worked like magic! Dairy Milk was on fire — it was the hottest chocolate in town and we couldn’t produce enough. We were growing 40% month-on-month. Then we did other memorable campaigns such as Kuchh meetha ho jaaye, Pappu pass hogaya… Rajeev Bakshi [then MD, Cadbury] was great when it came to seeing the big picture, and giving you the freedom to execute.

***

I was at the right place, at the right time. After Rajiv quit in 2001, Mathew Cadbury, one of the heirs of the Cadbury family, came to lead India; but he could not settle down and left within a year. The top job fell into my lap. I was CEO of Cadbury at 40! That gave me quite a kick. I’ve always been the youngest in most things — I had a double promotion in school, so was the youngest when I passed out of college and there-on was the youngest area manager, youngest branch manager, youngest marketing head and, now, the youngest CEO.

By then, I knew one thing clearly: we needed to keep things simple. You need to do nothing much to be a great company — set up the company on a fast growth track, for which my way was to create new categories to grow, not fight for market share; and secondly, make it a place where people love to work. The second part was already in place — it’s more fun to sell chocolates than toothpaste, hair oil and detergents!

For me, the best part as country head was that I was working for a British company — that largely left you alone to do what you wanted to do. I couldn’t have asked for anything better. We did so many things; we developed gifting and did so many new launches — Milk Treat, Chocki Celebrations, Rich Dry Fruit Collection, re-launched Perk and Picnic… and most importantly, built a great team.

After Cadbury acquired the confectionery division from Warner Lambert, we wanted to grow the candies business in India. But although we were pushing hard, we weren’t making progress. I understood why when I went on a field visit — the sales guy was clearly focusing on Dairy Milk chocolate and ignoring candy. He explained when I asked him why: one carton of Dairy Milk equalled 20 jars of éclair in sales, so it was easier to achieve targets by pushing the chocolate. Class A stores sell 80% of chocolate; chocolate requires depth, while candy required width.

I knew what had to be done — but there was resistance to my suggestion of having a different sales force for selling candy. Those were the days of consolidation and I was recommending adding an entire sales team! The global marketing head was sent to India to evaluate this. I told him, “Keep an open mind. I’ll take you to the market and you can take a call after that.” He went back and suggested the same thing.

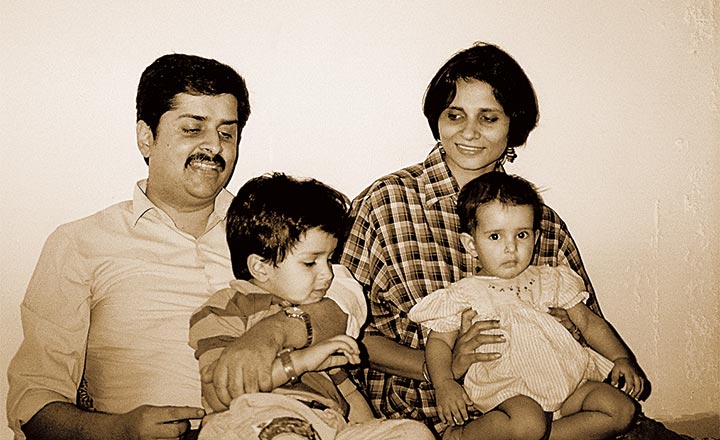

Working at Cadbury was like having your cake — or rather, your chocolate — and eating it, too. Just peeping into the fridge full of chocolate, both at Cadbury House and at home, was enough to make your day. My dear little children Abhay and Meghana also got some bragging rights — I convinced their friends that they had different kinds of chocolates for breakfast, lunch and dinner! All of their friends wanted to come to Cadbury House to see the secret place where hot chocolate flowed out of the tap and the shower!

***

It was our best year ever. October 2003, the senior management team was at the Shangri-La in Bangkok for our annual budget finalisation where we were also being feted as the best performing unit in the region. There was so much camaraderie that you get a high anyway, and then you are also actually high. Things can’t get any better, you think. And then comes the call: “Sir, CNBC is running this news that there is infestation in our chocolate.” We had an incident management team in Mumbai at the time, as most food companies do. Quickly, we put together a communication team, and I was back at Cadbury House the next day. The first thing I saw was the CNBC van — it was like a cold welcome, I thought to myself. It couldn’t be for the infestation, I was debating mentally — out of the 1 million bars a day of sales, infestation was found in about nine bars; could it be that big a deal? Man, what a nightmare it turned out to be…

For the first time in my life, I could see buri nazar wale tera muh kaala actually waiting to play out. Needless to say, I was the buri nazar wala, bure karam wala…and it was the local MLA who turned up with a tin of black paint to blacken my face! I was so worked up, I wanted to step out and talk to him; HR head Radha Menon told me to relax and sit tight — it was theatrics at play, nothing else. There was a call from someone at Sahara TV, saying they had found a chocolate with worms and were going to run the story; they wanted my comments but what was I going to say? Then there was a call from an old man in Rajkot: unbelievable as it sounds, he tried to blackmail us, threatening to report an infestation in our chocolates to the consumer court unless we featured his son in a Cadbury ad! Bizarre!

Sales dropped immediately, but much more so in the impacted regions — 40% in the first month, another 20% on top of that the next month. This was really bad news because, in the end, only what the consumer believed mattered. It was painful to hear that both in Maharashtra and Kerala our brand confidence survey showed a drop from 90% to 40%. We had asked just three, straightforward questions — would you buy Cadbury, would you buy it for your children and would you gift it; and the hard truth was consumer confidence was shattered.

It was not just customers, everyone looked so unhappy. Morale was down. I can’t forget the day my sales head came to me with a long face saying his wife and daughter were in tears — the child’s teacher had refused to let her distribute the box of Cadbury chocolates she took to school on her birthday.

There could have been no better way to build confidence but to make people actually see that we didn’t have a problem. I don’t remember whose idea it was, but it worked! We asked our sales staff to buy Cadbury chocolates worth Rs 1,000 from their nearby stores. If they found any infestation, they were to report it to the company and send across samples; if not, enjoy the chocolates! God, that lifted spirits instantly! One, everyone realised there wasn’t anything wrong with our chocolates and then they got to eat them, too!

Keeping up morale and keeping the faith are most important in a crisis. In the middle of all this, headhunters would call and say, “It’s over now. You should consider so-and-so offer.” I couldn’t believe it! I had to tell them, I was the captain of the ship that was in stormy waters and there was no way I was going to abandon the ship.

But the mood was still not really upbeat. In the end, the customer had to be convinced. I still remember the sales meet in Surajkund, outside Delhi, where everyone had a view on how to get back. I did not quite realise at that time the gravity of what this young sales guy — Amit Upadhyay — was saying. Driving back to the airport, it sank in what a wonderful suggestion that was. Amit was clear that the country took only two people seriously — Atal Bihari Vajpayee and Amitabh Bachchan. Being the prime minister, Vajpayee could not be our ambassador but Bachchan carrying the message would really convince people. The more I thought about it, the more I was convinced it was the right approach. Piyush was sceptical initially, as was Sanjay, our marketing director as they had already worked on a very strong emotional creative. But Piyush quickly sensed the point and before I knew it, he had spoken with Mr Bachchan and we were at Bachchan’s place post-dinner to see him.

We invited Bachchan to our factory to see for himself, for we wanted him to be convinced about it himself. It was his idea to shoot the creative at the factory. That ad worked very well and we were on the road to recovery.

Apart from the creative, of course, if we had not taken that visible action, we would not have gained back consumers. I have to hand it to Todd Stitzer, CEO of Cadbury; he okayed the capex for the new packaging machines, over a phone call! It was Rs 12 crore, not an earth-shattering amount, but sometimes, it can be hard to convince people; this was a welcome change. We still had people saying that double packaging was overkill; there was no point in increasing costs permanently. But we needed to act urgently and thank God, we did. We thought sales would bounce back in 12 months; no one imagined it would in six.

I remember Sir John Sunderland (global chairman of Cadbury) saying, “Bharat, you don’t realise it is such a privilege to be handling a crisis like this”, and intoning, “What is he thinking?” But perhaps he was right because but for the crisis, you would not know your friends from your foes and how important it is to have a great team, friends and family support who serve as sounding boards during such times. My wife and I would take short walks on the terrace dissecting the day’s events while Piyush and Madhukar (also of Ogilvy) would frequent Cadbury House so many times — it did not matter whether we had anything to discuss or not but just his being there felt so reassuring. Another evening, there was a media function and I was reluctant to attend. Aditya dragged me there, persuading me all the way that the crisis was nothing personal and I should just be myself. He stood next to me the entire time as though he were my bodyguard and then we went off for a hearty dinner at Delhi Durbar. I still remember those melting tikkas.

Food never fails to lift my spirits although, to my regret, I can’t eat rice with my fingers — that was beaten out of me at Sanawar! In Madurai, my lack of finger-eating skills made for an amusing incident. We were at Shree Ram Mess with delicious sapadu laid on the banana leaf and there I was, waiting for a spoon. Only thing was, there wasn’t a single spoon in the mess! They finally unearthed an old, bent utensil used for pickle but my team declared it unfit for my use. One guy immediately ran out and — Madurai being Madurai, there are stainless steel stores everywhere — returned with a dozen spoons, all for me!

***

Moving to Singapore in 2006 to head marketing and sales for Asia Pacific, as well as specifically handle China was a natural career progression but what an experience it was. I realised just how different India and China are after leaving the country for my first overseas stint.

I still remember the first group meeting I called in Beijing. The China CEO Kim Seng and six members of the leadership team were present, and no one spoke a word. It was like extracting blood from a stone. I would ask them what they liked about the company and they would look at Kim Seng, their boss and then stare at me blankly. I asked what we should do to perk up sales and I could almost see them thinking, “What kind of guy is this? He is the super boss; he should be telling us what to do.” I had to cut short the meeting and then meet each one individually; they were much more forthcoming then.

This was a world removed from my experience in India. Here, people competed with each other to express their opinions in group meetings — we could discuss and debate topics for hours and days, without reaching a conclusion. Chinese culture, on the other hand, is such that if you are the boss and you ask someone whether they want coffee, the reply will be, “Yes, I don’t want coffee.” It’s almost as if they are trained to say yes to everything. I learnt my lesson quickly — never ask for opinions in a group meeting.

The other lesson was to stick to tried and tested food. KFC became my default destination after my initial insistence on authentic food backfired miserably. I still vividly recall the meal at this restaurant in a small town close to Nanjing. The branch manager who was accompanying me repeatedly told the waiter we wanted only chicken or prawns, nothing else. And then came the chicken, with its wings sticking out, and the prawn with its antennae still moving! I decided there and then that at least when it came to food, I was not going to experiment any more.

Australia was just the opposite of China. What a bunch of fiercely individualistic people! Unless you established personal credibility with them, there was no way to get those guys to listen to you. Their behaviour was exacerbated by the fact that before Singapore, Australia was the regional headquarters and they contributed the most to the kitty. I would ask the marketing director what he thought of an idea and the immediate response would be, no, that won’t work. Every time they thumped the table, I had to thump twice as hard!

Japan lay somewhere between China and Australia, both literally and culturally. On my first visit to the Tokyo office, my boss Rajiv Wahi, our regional president and I couldn’t help but notice that the Japanese love fragrances — wherever you go, you’ll find yourself enveloped in some nice smell. Rajiv remarked lightly that what a hit we would have if we launched a gum that would fill the room with fragrance when chewed. All of us had a good laugh but to my astonishment, the R&D team actually worked on the idea and presented us a sample when we returned for a review meeting four months later!

***

In 2008, Cadbury appointed me as the global head of chocolates, and there was one company that immediately saw its bottom-line swell — Singapore Airlines! I kept the A380 in good use, travelling all over the world. After the “yes sir’s” in China and the “not possibles” in Australia, London kept me guessing. What did they mean when they said “interesting” (the tone was the cue to whether they thought it was good, bad or ugly) and “challenging” (really bad)? You would say, “Lovely day” and the reply — “Isn’t it”— would have you wondering whether they agreed or disagreed. Understanding the subtlety, understatements and self-deprecating remarks was central to getting things moving. Language and its nuances aside, understanding the expectation of a global board and its concerns also took some time.

And then, Kraft made the acquisition bid for Cadbury — in six months after the bid, we were acquired and from Singapore I landed up in Zurich. When you get acquired it is like joining a new job without having left the old one. You have to work hard to establish yourself and can’t live on your past glory. But now we were the largest chocolate company in the world, since Kraft with products such as Milka and Toblerone had an equally big chocolates business. It wasn’t as difficult to be the co-head of chocolates as much as it was to straddle the American and British ways; they are like chalk and cheese.

Cadbury used to be highly decentralised, so countries did not have too much difficulty with the centre; Kraft was just the opposite. Thankfully, I was by then part of the centre. That’s a trend that is becoming increasingly true for countries: individual countries such as India are becoming just the sales and distribution centres with Singapore or Hong Kong calling the shots. To win in India is still a massive task— you need to understand the local market well and develop a strategy accordingly. Europeans are more international, so it’s much easier for them; American companies have much more learning to do.

Working in all those different countries was truly fascinating — the world was my oyster! One good part of being an expat is that you get closer to the family. Especially in Zurich, where we were two hours from five countries; as a family, we drove more in the five years I was in Zurich compared with the 15 years earlier. And my parents always spent the summer with us.

For me personally, if those days had a lighter side, it was because Americans wouldn’t get Britspeak! My gags were lost on them most of the time. At a dinner in Singapore, someone from Kraft asked me about my previous assignment. I said, “I had damaged India enough so I was told to go and damage Asia-Pacific. I was heading India then moved to Asia Pacific before taking over as global head of chocolates.” He took me seriously and asked in a hushed voice, “Really? What happened?” The more you engage, the more you find yourself sitting at the bottom of this ski slope!

Again, on one of my trips to the US, someone asked me, “Bharraat, when did you come in?” I explained, “I came over the weekend; my daughter is in school here [Meghana was in Northwestern University and Americans call college school].” The person said, “You don’t look old enough to have a school-going daughter.” I said with a straight face, “Yes, in India, child marriage is rampant…” And then I realised, these people were actually taking me seriously! So, I backpedalled, “No, no…” One of them asked, “So, you are not married?” “No, no, I am married.” “So, it’s not your daughter?” “No, she is, but…” I was ready to bang my head against the nearest wall, wondering what I had gotten myself into. There are probably some people at Kraft who still believe I was sent to Zurich because I had done enough damage to India; and another set that believes I got married when I was a kid, or I have an illegitimate daughter, or both!

When I was leaving Cadbury in 2015, there could have been no better farewell for me than the flash mob on Mera joota hai Japani that the Zurich team organised. There were about 20 of them who’d obviously spent time and effort on getting it right. I was so touched and their choice of song was bang on. Nothing could have described me better. We had created the most diverse team ever — half of the team were men, half of the team were women; half from developed countries, half from emerging markets; one-third legacy Cadbury, one-third Kraft and one-third newcomers. Everyone was envious of our team.

That has always been the case. I have had great teams — such mavericks! It has always helped me to recruit curious all-rounders who are gentlemen/women, team players — and yet perpetuate a culture where everyone can thump the table and make their point. I can’t even think of having people in my team with whom I can’t spend time outside of work. Thankfully, I’ve never had to suffer anyone so far. And hopefully, no one suffered me either.

I couldn’t believe Mr. Madhukar Parekh when he said during our lunch meeting at Singapore that he had come all the way to just meet me. We were acquainted because Cadbury and Pidilite had won awards on several platforms together and we often bumped into each other. But he stunned me when, out of the blue, he said he needed me as partner on the board to take the company to the next level. I refused the first time, tried to dissuade him, citing my frequent travel and crazy schedule, which may not even allow me to make it regularly to the board meetings. But he came back after a month and said, “I have thought about this thoroughly. Even if you come for the meetings only twice or thrice in a year, it’s okay.” When somebody gives you that level of respect, you don’t have the heart to say no but, still, I asked him to look me in the eye and tell me he was really serious — most Indian promoters want to get professionals on board but not everyone is truly willing to take their recommendations seriously. But Parekh was persistent. And the Fevicol bonding began.

Parekh truly walked the talk — Pidilite today has one of the most distinguished boards in the country. The board retreat for three days was a great learning event — everyone was learning more, debating ideas, and enjoying... And then, one fine day, Parekh invited me for dinner and told me that the family and he were convinced that Pidilite needed to have its first non-family head and they wanted me to be that person! I said this was not part of my plan and I may need a long time to think, may be six months. I couldn’t believe it when Parekh said, “Take a year.” I don’t know what gave them that kind of confidence in me. What gave me the confidence was that I had been working with the board for five years, had spent a lot of time with the other board members and the family and I had Parekh’s word that he was ready for a makeover. I did ask him repeatedly if he was really ready— he was, after all, recruiting me to be me, not him. I was from a multinational company and that would mean I would do things in a certain way. He was running a very successful company in his own entrepreneurial way; why should he change? But I could not have become Parekh Version 2. And he had to be comfortable with the changes I would make.

Alka and I were sitting in South Beach, in Florida, discussing if I must make the switch. Of course, my heart was always in India. Unlike most friends and colleagues, I was always clear I would return to India. I am glad I made that decision because it was clear that if you have not worked in the home market, it’s highly unlikely that you’d get the top job at a large American multinational. You could get a number of No. 2 positions, but No. 1 was a tough ask.

It’s getting difficult for multinationals anyway — earlier when their home markets were growing, the cost of experimentation appeared low, so they could experiment and grow. Now that their home markets are not growing, most multinationals are focused on costs rather than growth. The same cookie cutter strategy then applies, be it emerging markets or developed markets. That’s also the reason organisations are becoming increasingly matrixed. New products and strategy is dictated by the headquarters, reducing the sense of ownership. On the other hand, if you are with a Pidilite or any other Indian home-grown company, you are the owner of the brand.

The idea of taking the reins of an Indian company and leaving a legacy is sort of romantic, dreamy, idealistic thinking… I was excited. With a $5 billion market cap and zero debt, we have the capacity to be a global player — that is exciting. I can leverage every bit of what I have. The secret to great companies, ones that have galvanised growth, is just one thing — making the place a pleasure to work at.

I was glad somewhere that I was doing okay on Papa’s benchmark. When I started working, Papa told me three things — soldiers are never good or bad: there are only good and bad generals. So, if anything goes wrong, first look in the mirror. Two, when you put your head on the pillow, you should be able to sleep within 10 minutes. If you face any dilemma, think that you should never have your father look down on anything you do. And most importantly, remember that in the army, there are two kinds of generals: those whose troops love them and those whose superiors love them; ensure both love you.

Post script: What B-school [never] taught me

- The most crucial part of leadership is dealing with people and building teams, something B-school does not teach you. Pushing people towards performance is fine but how, is the question. In a growing organisation, it’s important to stretch, but the stretch has to come with a smile.

- Keep your ear to the ground. In 1997, a pigeon race was conducted in which thousands of birds flew from Nantes in France to southern England. But there was no sign of the pigeons across the Channel. Researchers found that the Concorde flew on the same route and the birds got disoriented by the sound and lost their way. Birds fly by listening to atmospheric infrasounds, which were disturbed by the supersonic aircraft.

Companies fail because they stop listening to the infrasounds. If you want to know the truth about your company, talk to your fieldstaff and your management trainees. They are the most fearless lot, and if there is any chance of getting the truth, it’s only from them. I spent my first six months at Pidilite only meeting employees — each one of them. Make yourself approachable, and make everyone talk to each other. We’ve adopted Workplace by Facebook, so as to encourage two-way communication — it’s fun, it keeps people connected.

- Keep the messages simple: At Pidilite, I asked what are the two things we should never change about the company, and two things we must change.

- The best inputs on the market can come from your sales force; never ignore them. At Cadbury, based on feedback that the 5-star bar was sticking to consumers’ teeth, we improved the product but could not explicitly tell the consumers that it would not stick to their teeth anymore. A creative was made based on the nursery rhyme “Johnny Johnny”. It showed an old man frantically searching for his chocolate bar in a bookstore, which his grown-up son is eating; when the old man demands the younger one open his mouth wide, he does, showing that the chocolate has melted away. I thought the ad was a little downmarket, but the sales force loved it, and so we went ahead; it was an outstanding success. In another instance, we did a campaign styled like an MTV music video — the idea was to marry mass and class. When I showed it to the sales team, there was deathly silence. The agency, though, insisted that it was a great creative and people would love it. So, we went ahead with it; it was a disaster and we pulled out quickly. People on the ground always have higher strike rates in judging what will work. Another lesson from that experience was, you can’t take the customer non-seriously.

- You cannot penalise people for failure. It’s a given that three out of 10 initiatives will fail. But as long as the experiments are well intentioned, hold each other’s hands and move on. In India, the cost of failure is little — it doesn’t cost too much money to experiment. Err on the side of experimentation rather than extreme caution.

- Stay the course. At Cadbury, we didn’t get boxed gifting right for a long time — it was challenging because in foods, what you make at the factory is not the same thing you put in your mouth. To deliver the same experience, your supply chain has to be fixed. We kept at it till we got it right. On the contrary, Cadbury should have been far bigger in candy, but Perfetti is much bigger and that’s because Perfetti stayed the course while Cadbury has not. Cadbury had launched Googly kachcha aam years ago, but gave up too quickly. Now the same product by DS group — Pulse — is a Rs 100-crore brand. It’s because of sheer persistence.

- No company can survive on discounts or more credit. If you keep cutting stuff you won’t succeed. You can win only if you have a better product, service or brand.

- Back your products based on potential, not their present position. Pidilite bought M-Seal for less than Rs 20 crore in 2000. And then, they built it up with the 70-second Ek tapakti boond ad. Now, the brand is far in excess of Rs 100 crore. Identify unserved, underserved segments, fill it with a brand and back it.

- Focus on people’s strengths and not their weaknesses. Each person has a spark of excellence — make sure that is in play when they are at work. All of us will have (and will die with!) some weaknesses.

- If you have to succeed in a multinational career, you need three things in a spouse/partner. Adaptability, support and the ability to manage the home. If your partner is unhappy, your career is threatened. Alka was always upbeat — she took German lessons, blended into local culture wherever we lived, shaped the kids, and held the mirror for me, always. (The higher you fly in your job, the more you are kept rooted by your family. With Meghana and Abhay, now I have three walls, each holding a mirror!)