It was an age of adventure, it was an age of conservatism. It was the season of Alisha Chinai’s unapologetic lust for a bare-chested Milind Soman, it was the season of Alok Nath’s forehead creased in worry for our sanskari souls. We were all headed for revelry, and we were all wondering if we should, really. With due apologies to Charles Dickens, this mutilation of his prose could describe India in the nineties, when it was torn and living between videsi-desi worlds.

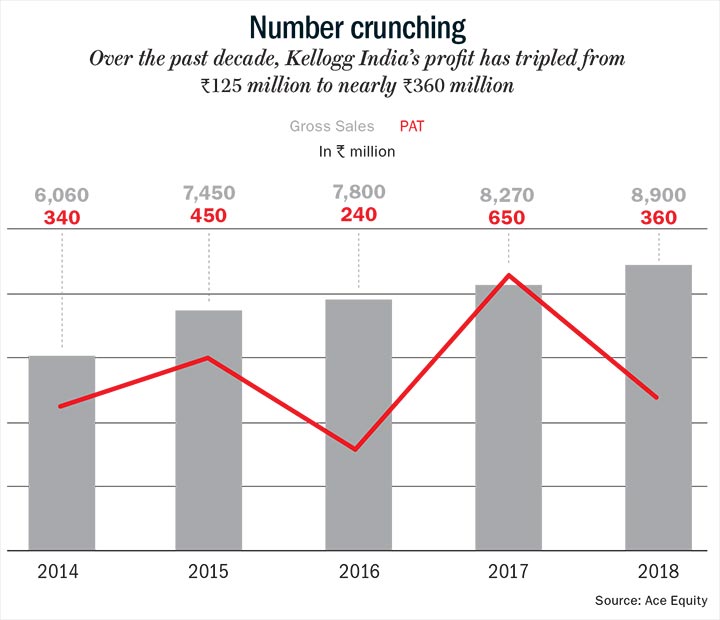

It is also when Kellogg came to India. Steaming idlis and buttered parathas were still the morning staple, and cereals were dismissed as flaky (pun intended); but the Michigan-headquartered company was determined. Today, that has paid off, with Kellogg capturing 55-60% of India’s Rs.26-billion cereal market. In the past decade, its sales rose from Rs.1.8 billion in 2009 to Rs.8.9 billion in 2018, at a compound annual growth rate of 19.4%. Its profit tripled from Rs.125 million to Rs.360 million, in the same period (See: Number crunching). About 95% of its sales come from the cereal category (the rest comes from premium chips brand Pringles).

Its phenomenal success has largely come from understanding its target audience well, as people who are “nutrition seeking, time starved”. Essentially, kids and young adults, who are short on time and yet need their breakfast to be quick and healthy. “We believe 65% of India falls under this category. Our lives are not getting easier, and talk about a kitchen-less world could soon come true,” says Mohit Anand, MD of Kellogg South Asia.

The cereal company had just been settling in, fluffing up its pillows, when new challenges have risen. Competition has upped its game and hungry start-ups have stepped into the breakfast category. Also, Indians are now cutting out sugar from everything (except dating apps) and processed cereals are seen as loaded with ‘White Death’. So, the 120-year-old multinational has to be on its toes and expand into newer segments if it has to remain relevant to the target audience that it has meticulously identified.

Unexpected turn

When Kellogg arrived in 1994 in post-liberalised India, with its booming middle class, it had expected to taste instant success. That had been its experience in other markets. Founded in 1906 by WK Kellogg, the US-based multinational has always been flush with money and has global expertise with presence in over 180 countries (150 countries when it came to India). The company set up a local manufacturing plant at Taloja, on the outskirts of Mumbai, in 1993 and launched its first set of products — cornflakes, wheat flakes and Basmati rice flakes.

However, the initial years were a struggle despite the frenzied launch. In fact, in 2004, Carlos Gutierrez, the then chairman and CEO, Kellogg Company, was asked if there was need for a course correction after the brand’s first decade in the country witnessed a tepid response. Speaking to The Economic Times, Gutierrez had said, “It sounds like a long time, but isn’t really, when you are trying to develop a new category.” He said they had waited 20 years in Mexico to turn a profit, and will do the same in India. Patience is a virtue our country demands and graciously rewards.

There were yet other lessons that Kellogg was to take from India. Hareesh Tibrewala, joint CEO of Mirum India, a digital marketing agency, says the company’s communication focus was on running down Indian breakfast items as being unhealthy. “This did not go down well with our moms and wives who labour in the kitchen cooking our meals,” he says. Then, there were culinary quirks too. Cornflakes are usually had with cold milk in the West. But most Indians prefer to pour hot milk and add sugar to the flakes, leaving them soggy.

This ‘mush’ was priced at a premium too. A 100 gm pack of Kellogg cost Rs.21, whereas Mohun’s, its closest domestic competitor, was sold at Rs.16.5. As a result, most people ended up buying cornflakes as a ‘one-off novelty’ purchase.

Besides the communication and product hiccups, the company was facing troubles in distribution. Devangshu Dutta, chief executive of retail consultancy firm Third Eyesight, says that Kellogg was used to operating in developed markets where modern retail format was fully established. On the contrary, the Indian retail boom was still a few years away.

Despite the setbacks in the nineties, to the company’s credit, it dug into its deep pockets and decided to wait it out. In the interim, it launched globally successful products such as Chocos, Frosties, cereals in local flavours Mango Elaichi, Coconut Kesar and Rose under its ‘Mazza’ series, and Chocos Breakfast Cereal Biscuits. While the former two worked well for the kids segment, the latter didn’t cut much ice with the consumers.

But Kellogg trudged on. It absorbed losses, even while it was reinventing and re-positioning the brand in the early 2000s. Their first big inflection point came around 2007, says Anand, after they exited from their non-core business such as biscuits and decided to focus on their core — cereals. From just the top metros, Kellogg expanded to over 60 towns and made the brand accessible at more retail touchpoints. “We also launched more affordable packs below Rs.20. A combination of these led to acceleration in sales,” says Anand.

From thereon, the strategy has continued to be the same — diversifying into smaller packs, ramping up distribution, and intensifying its marketing effort. “We keep moving with where the segment is moving, filling need gaps all along,” says Anand. Kellogg now has a total of 28 variants including Ragi Chocos, Real Kesar Pista Badam Corn Flakes, Real Thandai Badam Corn Flakes and Special K for women (Even its premium chips brand Pringles, which was introduced in India in 2014, offers Indian flavours such as Fusion Chutney and Pringles Desi Masala Tadka). The packaging of the cereal was also changed to include a blade of wheat and rising run, inside the familiar red band.

Alongside, distribution has been expanded to cover more than 2,700 towns and over 550,000 outlets across India. A strong local manufacturing base has been built, which helps in keeping costs low. The company operates two fully-owned manufacturing facilities -— besides the one in Taloja, there is one in Sri City, Andhra Pradesh — and two third-party facilities. Two-third of the total production of 30,000 tonnes is manufactured at the company’s own plants.

Kellogg’s fastest selling SKUs are reportedly priced between Rs.5-99, accounting for over 20% of its sales. Anand says, “They will undoubtedly continue to play a significant role in driving penetration for us.” Meanwhile, the larger refill packs, priced between Rs.250-520, cater to its repeat customer base.

Pinakiranjan Mishra, partner and national leader, consumer products and retail at EY, says that the urban population belonging to high and middle income groups is responsible for 96% of India’s breakfast cereals consumption. “To ensure category penetration in low income groups, smaller packs at affordable prices need to be placed using various distribution channels, as this initiates more trials,” says Mishra. Rural India, which is 70% of the country, remains an untapped opportunity for Kellogg, admits Anand, but adds that there are significant opportunities in urban India itself. “We will look to keep the focus there for the foreseeable future,” he says.

The focus on keeping it niche is also extended to Pringles, which is imported from Malaysia to be sold in India. The top three slots in India’s potato chips market have been taken by PepsiCo, ITC Group and Balaji Wafers. These companies manufacture their chips locally, operate across price points and have solid distribution ranging from supermarkets to kirana stores. The market is growing at a tempting pace, from Rs.61 billion in 2015 to Rs.110 billion in 2019, but Kellogg’s chips is not making the crisp profit it could, being priced at a premium.

New hurdles

While the brand is dealing with these long-standing barriers, new hoops of fire are being placed in its path. When Kellogg made its entry in the mid nineties, there were almost no ready-to-eat alternatives — barring a few local competitors — but that is no more the case. In the same year as Kellogg, Bagrry’s entered the arena and today, has made solid inroads into the breakfast segment — its sales has grown from Rs.385 million in 2009 to Rs.1.2 billion in 2018. PepsiCo, with Quaker Oats launched in 2006, also found many takers. In 2010, Marico, too, came to play with Saffola Oats and has subsequently introduced multiple savoury variants such as masala oats. Saffola Oats’ contribution to the parent company’s sales was just 1% in FY15 and increased to about 2-3% in FY19. More recently, start-ups such as Bengaluru-based Kottaram Agro Foods’ Soulfull has tasted success with its range of breakfast cereals.

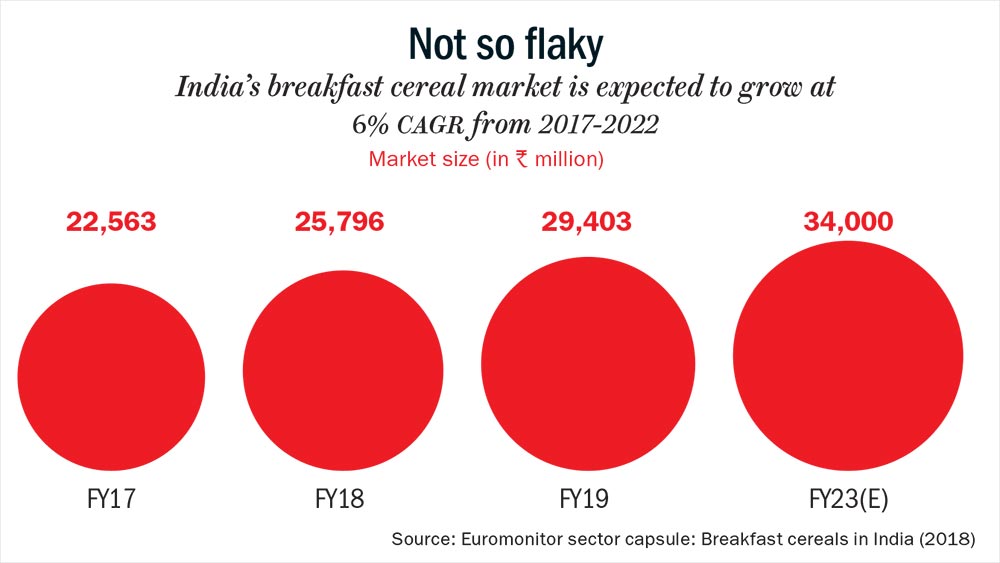

It goes without saying that India is a market that has always preferred hot and savoury meals. So, while the overall breakfast cereals market is expected to post a CAGR of 6% from 2017-2022, with sales reaching Rs.34 billion by 2023, Mishra says that the market for muesli, granola and hot cereal products is growing at a faster pace (See: Not so flaky). From 2017 to 2022, hot cereals are expected to grow at a CAGR of 6.33%, while the ready-to-eat cereals are expected to grow at 6.14%, according to market research firm Mordor Intelligence (Hot cereals include oats, oat bran, wheat bran and porridge whereas ready-to-eat cold cereals include cornflakes, wheat flakes, choco flakes and muesli).

What’s more, even Indian breakfast staples such as upma and poha can be made à la Maggi noodles, by simply adding hot water. Then there are idli and dosa batter aplenty. Options are only set to increase, and Quaker and Saffola have raced ahead in this innovation game, notes a senior food leader on condition of anonymity, and adds, “These two brands took oats and made upma, idli, poha out of it. But Kellogg looked at the brand from a cornflakes lens and not from a breakfast or food one. If they had broadened their definition to, say, what food Indians would like to have, it would have been different.”

But Kellogg has tracked this shift, and dipped its toes into the rapidly changing waters with a range of muesli in 2005, followed by another of oats in 2010. Its Masst Masala oats was launched in 2016. Consequently, while cornflakes and chocos are their mainstay, granola and muesli have also been witnessing double-digit growth. Dutta says it is not too late, from the point of view of market development, for Kellogg. The market is nascent, and there is enough room for all to grow.

Sentiment at the company does not convey any sense of urgency though. “India is such a wide country that you are not competing with any one thing, you are competing with everything,” says Anand, adding, “our aim is not to compete, but to stay meaningful in the lives of consumers and drive the cereals category.”

As Kellogg floats along, at a Zen-like pace, consumers are fleeing the new terror — white sugar. It is a global trend and, in India, there is consensus that breakfast cereals that were packaged as healthy alternatives are actually not so healthy. “Cereals are brought to us from the West, where breakfast is usually coffee and cupcake, or coffee and donut. So, cornflakes are healthier as its sugar content is surely lesser than that of a donut. But, if we compare it to the breakfast options we have in India, it is not healthier at all. It is convenience food, not healthier food,” says celebrity nutritionist Pooja Makhija.

She says that the focus of these food companies is to provide convenience and taste. And taste comes either from fat (present in ready-to-cook foods) or sugar (present in cereals), making cereals a low fat, high sugar convenience food. Anand disagrees. “There is a constant debate on HFSS — high fat sugar and salt. We are ahead of the game in not just delivering nutritious cereals, but also having fairly severe targets on ourselves to reduce (sugar content),” he says.

In order to affirm its claim, Kellogg launched Global Breakfast Food Beliefs report in 2015, which notes that the threshold level of total added sugars in its cereal has to be 10 gram per serve. “We are proud to state that Kellogg India is now food belief compliant and, in the process, has successfully reduced 850 tonne of sugar last year,” he says.

The sugar reduction has turned out to be a sweet deal for the company, as the message of a convenient and healthy option sits wells with its time-pressed consumers. Prem Narayan, chief strategy officer of Ogilvy India, says, “Category creation is no mean feat, but Kellogg built it by reiterating the relevance of breakfast and the message of ‘nutritious grains of India served in a convenient format’.” It was done by drawing on its global experience, deep understanding of the cereal market and formidable marketing muscle.

Kellogg’s iconic mascot Cornelius “Corny” Rooster has proved to be a resilient bird so far. The brand built a road where there was none and so it will find its path again. What will be interesting to watch is how it will do it.