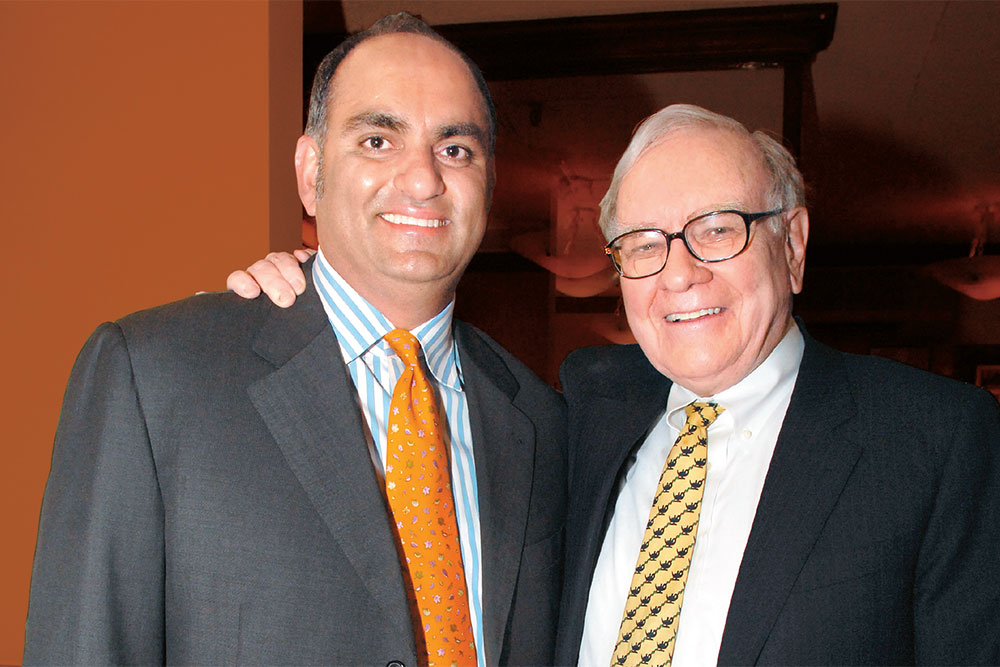

The $650,000 he paid to win a lunch with his idol was guru dakshina. For Mohnish Pabrai, the truest Eklavya of the investment world, the guru is none other than Warren Buffett. The only difference is that, in this case, the guru had more honourable intentions — the hefty, auction-determined bid price would not rob the shishya of his greatest skill; instead, the money would go towards San Francisco’s Glide Foundation, Buffett’s favourite charity. For Pabrai and his friend Guy Spier, who bid jointly for the lunch, it was a masterstroke, because the charity was anyway on their agenda, having taken a leaf, once again, from Buffett’s book. And so, while they contributed to the charity, they also bought themselves a chance to get up close and personal with the guru. “I had a huge tuition bill to pay — this was only a fraction,” Pabrai said at the time of winning the lunch in June 2007.

In the egocentric world of investing where every Johnnie-come-lately is out to make a fortune, convinced his idea is the best ever, Pabrai has left his ego way behind in pursuit of the riches that he will eventually give away to people unknown to him — poor but bright students in India. But then, Pabrai is no average Joe straight out of B-school, thirsting to prove himself in the world of high finance. Rather, he is someone who has learnt hands-on from a very early age how business works, started his own business, sold it and then started his own fund with a capital of $1 million. Now, Pabrai Investment Funds has a corpus of over $485 million.

The 49-year-old Pabrai grew up in Mumbai, running his father’s business, which turned out to be the best preparation to become a good investor. “I was lucky in that my father ran a whole bunch of businesses, started them, grew them and bankrupted them! Many of these businesses were very highly levered and they would blow up because they had no stability.” From the age of 12 or 13, while their father travelled, Pabrai and his brother would look at cash flows trying to figure out how to get past the next day, just one day, every day. “I later realised that by the time I was 18, I had finished many MBAs. The period I went through with my dad helped me crack business models much faster than others of my age who were much smarter than me.”

It’s an unusual story. And Pabrai has an interesting scientific explanation that sets me thinking out loud on what you need to do for your children if you want them to excel in any specialised field. It’s an off-tangent subject, but also the reason for the success of many great men, including Pabrai, so perhaps the detour is excusable. The human brain, Pabrai explains, goes through two periods of very rapid change. At birth, babies have a small, underdeveloped brain because the birth canal is too narrow. But during the first five years, the brain is the fastest-growing organ and a lot of change takes place then.

After the age of 10 or 11 until about 19-20, in what is usually referred to as adolescence, comes the second period of massive change. During this time, the amount of grey matter in the brain actually goes down as the brain prunes away matter that is not being used. The synapses or the neural pathways that are being used become conditioned in a certain way and the experiences you have during the teenage years have a lasting impact on you. “So, ideally, you want teenagers to specialise in a particular vocation. The system — US or Indian or any other — though, forces you to be a generalist. You will go to high school and study a variety of subjects. There is no specialisation,” says Pabrai.

He cites the example of Bill Gates — as a child, Gates would sneak out of his parents’ home at 11 pm to practise programming on the school computer till 5 am, when he would return home and sleep. By the time he was 19 or 20 years old, Gates must have spent about 15,000 hours writing code. His neural circuits were wired in a way that even someone who spends the same amount of time on programming from ages 20 to 50 won’t be able to replicate — it’s all meshed in, Pabrai points out. “The same applies to Steve Jobs, Michelangelo and Leonardo da Vinci. Why, even Buffett bought his first stock at the age of 11,” he adds. “Buffett ran a whole bunch of businesses before he was 16 or 17 years old.”

Pabrai’s friend Guy Spier, who manages the Aquamarine Fund (and who shared the lunch with Buffett), says watching his father fail and succeed many times has helped set Pabrai apart as an investor. “He has a deep understanding and awareness of life and humans. As such, the vicissitudes of life don’t affect him the way they affect other people,” he adds. Apart from the experience he gained at his father’s side, Pabrai’s biggest learnings would come from Buffett. He first heard of Buffett in 1994, when he read The Making of an American Capitalist by Roger Lowenstein on a friend’s recommendation and, “a light bulb went off immediately”. For the next four years, Pabrai continued running his business and managing his own portfolio, based on what he’d picked up from reading Buffett. In 1998, he attended the first Berkshire meeting. “I had just bought my first BRK A share so I could attend the meeting but it was not registered in my name before they sent out the meeting notice. So I wrote to Warren asking for a ticket. He immediately wrote back with the ticket,” says Pabrai. He’s attended every BRK shareholder meeting since then for the past 15 years.

It’s not just Buffett. Pabrai is a big fan of Buffett’s partner, Charlie Munger, as well. “The biggest highlight for me, even more than the Buffett Lunch, have been the meals I have had with Charlie. Buffett has a veneer of diplomacy; Charlie is completely open. It was amazing,” says Pabrai, telling us he has been for lunch and dinner twice at Munger’s home in Los Angeles.

There is a reason behind Buffett’s diplomacy — he is very cognisant of what comes out of his mouth because he knows it will fly across the world and some of what he says could have a detrimental impact. “Warren would never tell me that ‘I am telling you something not to speak to the world’. He just assumes that whatever he says might get to the world, so he is just more reserved about it,” says Pabrai.

The Buffett Lunch

For all the adulation that the world confers on him, Buffett’s barometer is not how the world thinks about him or his actions but how he thinks about himself. That was a stand-out insight for Pabrai during his lunch with Buffett. As Pabrai, wife Harina Kapoor and their two daughters, along with Spier and his wife, sat down for lunch at Manhattan steakhouse Smith & Wollensky, within minutes a “grandfatherly” Buffett made the families comfortable. “I don’t eat anything I wouldn’t touch when I was less than 5,” he joked with the girls as he ordered a medium-rare steak with hash browns and a Cherry Coke. And then, he said something cardinal, Pabrai recalls. “Buffett said you can live your life using either an inner scorecard or an outer scorecard. Then, he added, ‘If you were the greatest lover in the world but known to the world as the worst, would you prefer that to being the worst lover but known to the world as the greatest? If you know how to answer that question, then you kinda know how to go through life.’”

The inner scorecard has an very important implication in terms of the way you go about doing business. “Warren will not do a transaction with people he does not like, admire or trust, no matter what the returns are, because he is driven by the inner scorecard. But most people don’t think or act that way. They think, ‘I have a deal to close; so what if the guy is a jerk’.”

Cloning strategy

Buffett has been such a source of inspiration for Pabrai that when he decided to set up Pabrai Funds in 1999, he lifted Buffett’s partnership structure. It was the best possible structure, with no conflict of interest. If the investors made money, you made money and if they did not, you didn’t get paid either. Pabrai Investment Funds does not charge any management fee; instead, it takes a share of the profit after a certain hurdle rate.

Copying the partnership structure where interests of the manager and the investors are aligned was just the first step. Pabrai also openly talks of cloning other great investors, a strategy Munger himself has endorsed. At one dinner meeting with Pabrai, Munger said that if an investor just did three things, the end results would be vastly better than the rest. One, look at what other great investors have done. Two, look at cannibals — essentially, businesses that are buying back huge amounts of their stock — and three, spin-offs. And, Pabrai came in for special praise at this year’s Daily Journal meeting, where chairman Munger mentioned that Pabrai has followed Buffett’s principles the best. “It’s this old-fashioned stuff that really works. Now, I don’t say it works to create a money management business, unless you have one like Mohnish’s, which is a copy of the Berkshire Hathaway system down to the last comma. By the way, he’s rich and happy,” Munger said. “He copied a good system. How many people do? There are not that many Mohnish’s.”

Pabrai’s investment radar is no index, nor is it any other financial model or the usual filters. His starting point is the 13F disclosures — an SEC-mandated quarterly report of equity holdings by institutional investors with over $100 million in equity assets under management — of all the investors he thinks highly of. Then, he analyses those companies to further understand the business better. “It is a phenomenal starting point for doing homework because some great mind has processed it and actually gone through the process of making a capital commitment to it. You are way better off looking at that 13F and doing research versus looking at every stock on the NYSE.”

It’s a strategy that makes immense sense but few people take that approach. Pabrai understands why. “Most people are not willing to do that because to some extent you have to leave your ego at the door and say, ‘I believe these guys are smarter than me and I can learn from them’,” he points out. In reality, few people have the sort of maturity to make that confession even to themselves. “In general, cloning seems to be a very difficult concept for most people, which is great for me!” laughs Pabrai.

Pabrai has taken a whole host of ideas from others. He lifted an idea from Seth Klarman of Baupost, who has an excellent track record and has been acknowledged as a good fund manager by Buffett himself. The company was called CapitalSource and over a period of 18 months, Pabrai more than doubled his money in this investment. And then, he picked up Bank of America, Goldman Sachs and General Motors — ideas that came from Berkshire Hathaway. Now he owns Chesapeake Energy, which came from reading Outstanding Investor Digest in which Longleaf Partners had talked about the stock. “A large portion of Pabrai Funds’ portfolio is cloned ideas,” says Pabrai.

In fact, the only investment he owns currently that is not cloned from somewhere is a small company called Horsehead Holdings. This was a business Pabrai read about in Fortune in late 2008, when the magazine published a list of 10 stocks to buy after the market had collapsed. The stocks were classic Ben Graham net-nets, which meant they were trading below cash. You could liquidate the business and just the cash was higher than the market cap. “I was intrigued by the list and looked at all 10 of those businesses. One of those businesses was Horsehead and we took a position in it. That was almost four years ago and we still own that position. So far, it is more than a triple,” says Pabrai. “Today, if you look at our portfolio there is not a single stock we own that you can say was bought after we looked at the entire universe of stocks and ran a screen and so on,” he adds.

That does not mean these closed ideas are always spot on — but, thankfully, in this business you don’t have to be right all the time. You have to maintain a decent batting average — you will be wrong once in three times anyway, and that’s perfectly fine. How do you deal with cloned investment, we ask Pabrai. For most of us, accepting our own mistakes is much easier than accepting other people’s, especially when you start with the assumption that the other guy is actually better. “Conflict happens all the time, and you always have the option of not investing if you are not convinced,” says Pabrai. He offers his own track record as a case in point. Pabrai himself has not made any investments since June 2012, a period where both Berkshire and Longleaf have made several investments. “I look at the stocks bought and sold by all my heroes. But for me, in a year, if I can find even a couple of good ideas, that is enough. In 2012, we found three great ideas. In 2011, we found at least two good ideas. If we can find two or three in a year, we are doing well,” he says. The key is to be patient and happy doing nothing, “which I am good at,” adds Pabrai, reminding us of Munger’s oft-repeated quote, “Money is made not in the buying and selling but in the waiting.”

In a market such as India, where investors do not run very concentrated portfolios, can the cloning strategy work? It can, if you follow the golden rule. When you choose whom to clone, track record aside, you need to be sure that your hero himself is placing enough faith in the stock. So the stock can’t be No. 13 on his portfolio with a 3% weightage. “If I look at the portfolio of someone and they own more than 15 stocks, the thing I am most interested in is the largest position. If they don’t have a position where they put 10% of their assets, then we don’t have much interest in looking at the portfolio. It is not something where they have really made a bet,” says Pabrai. “You can look at all kinds of portfolios to clone but first of all you need to understand the framework those guys are using.” Apart from Buffett, Pabrai’s heroes are other renowned value investors such as Longleaf Partners, Greenlight Capital, Pershing Square, Third Avenue, Baupost and Fairfax.

Identifying the right stock is just one thing — understanding what Albert Einstein called the eighth wonder of world is what actually makes all the difference over the long haul and that, again, is something Pabrai picked up from Buffett.

A lesson in compounding

Like almost every child in India, Pabrai grew up listening to the tale of the king who promised the inventor of chess anything he wanted. The inventor asked, not for riches, but a grain of rice for the first square on his chess board; two for the second, four for the third and so on, doubling the amount on each square. The king agreed gladly, until his treasurer calculated just how many grains would be heaped on the final, 64th square — 18.4 billion trillion. That’s more rice than is available on the entire planet.

Pabrai estimates that it works out to 464 million metric tons, which would cost some $300 trillion to acquire, assuming prices stayed constant. That amount could be paid — barely — if “every man, woman and child on the planet gave the creator of chess everything they owned,” says Pabrai.

That’s how compounding works, and Buffett’s earnings history is a textbook example of its power. In 1950, Buffett had $9,800. Pabrai calculates that in the 44 years between then and 1993, Buffett had compounded assets under management at 31% annualised — the $9,800 had grown to nearly $1.4 billion. And this doesn’t include the millions he’d made from running the Buffett Partnerships or compounding those millions.

Pabrai decided to try out the power of compounding for himself. In 1994, he had sold some business assets and had $1 million after taxes in his bank. He did some calculations and hit on 26% as the “magic rate for compounding”, where money doubles in exactly three years. Do this for 30 years and you would be on the chessboard’s 11th square (210) — that is, the initial sum would have grown 1,000 times. Pabrai was 30 years old and decided to put the million into the “Mohnish compounding machine” with an attempt to generate 26% a year for 30 years. If all went as planned, the $1 million would have increased 1,000-fold and he would be a billionaire at 60 (there would be a day job, meanwhile, to take care of living expenses and “taxes for at least a few squares”). “Even if I missed my goal by 90% or even 95%, I would have $100 million or $50 million — and I saw nothing wrong with those numbers, either,” he laughs.

But compounding is not about a straight line upwards, as may appear from some of the most talked-about Buffett investments. So we ask Pabrai this irresistible question — how do you evaluate an option of higher lumpy returns versus lower smooth returns; how do you evaluate the investment, especially when you know that compounding works best when you do not look back or look down from where you are? For Pabrai, the answer is crystal clear. “Great investments are not going to come with smooth earnings. That is highly unlikely. So lumpiness is something you have to be very comfortable with.”

He points out that even in great consumer companies such as Nestlé or Hindustan Unilever, which on the surface look fairly consistent, when you drill down and look at what they are experimenting with, whether they are trying to build a brand or grow it, you will find several hits and misses in that space. “You don’t see that in the big picture because it is a small part of the equation. But you have to be willing to allow for that.” Companies such as Nestlé have a 30-35 year planning cycle and they are willing to lose money on a business for 10 to 15 years before they make money, Pabrai adds, saying the same is true even for companies such as Google and Apple.

The circle of competence

Unlike many investors who prefer to build their position over time, allowing for cost price to average out in case the stock falls, Pabrai thinks differently. “If we decide to pull the trigger, we would love to buy the entire stake in one day. But I am almost resigned to the fact that I am never going to get the bottom price of what I am trying to buy. If the business is cheap, is in your circle of competence and you can deal with the lumpiness, then it is perfectly fine.” The essence, then, is to operate within your circle of competence.

Charlie Munger, for instance, would say that a well-diversified portfolio needs just three or four holdings. And if you stick to your circle of competence, it is likely that you will make fewer bets and you will know the businesses really well. “A concentrated portfolio is the only way you are going to have a big chance of doing better than the averages. If you have 30 companies in your portfolio, you are not going to know the 30th business as well as you know the first business and that will hurt you,” says Pabrai, illustrating with an example. If you lived in Cedar Rapids, Iowa, or Amravati, Maharashtra, you could buy the McDonald’s franchise, the Ford dealership and the best apartment building in that town and, even if you own fractions of these businesses, you are done.

To an outsider looking in, you would signify extreme geographic concentration. But if you grew up in that town, you would know which is the best apartment building and the best dealership – that edge is extremely important. It is but obvious that you would not have the same edge if you were in Amravati and you decided to go to Guindy, Tamil Nadu, and replicate the strategy there. Someone who owns these three assets, Pabrai says, is probably going to do extremely well over a lifetime of investing, with no activity and by just sitting with those assets, barring some extreme event, such as an earthquake.

Giving it all away

Then again, Pabrai’s copy-the-best strategy is not restricted to only stock picking. He has also chosen to copy Buffett in something that most of the world, especially Indian businessmen, still find very difficult to adopt — philanthropy. Pabrai and his wife Harina have decided to give most of their fortune to charity. “Many more people than just Guy Spier and a few groupies should be cloning Mohnish’s approach — it would make the world a better place,” says Spier.

Emulating Buffett, Pabrai had assumed he would let the wealth compound into his 70s and then give away a much larger sum. But Buffett has also said that it’s far easier to make money than give it away effectively, and so sometime in 2004 or so, Pabrai and his wife decided “it was time to start giving some of it away”. The aim in setting up Dakshana Foundation the following year was to give away 2% of their networth each year, “getting good at philanthropy and learning from our mistakes rather than blowing the whole wad at once,” Pabrai explains.

Most charities are run by people who have phenomenal hearts but very little head, so they’re not going to be anywhere close to optimising or even utilising the resources at their disposal. At Dakshana, Pabrai says, the aim was to bring to philanthropy the same rigour and disciple he employs in investing. “Too many charities fail to focus their efforts and instead employ the fairy dust approach, sprinkling a little cash here, a little there. And so, they have little impact. I wanted our philanthropy to have more impact,” he says.

It’s not just about the decision to give; the way in which you give is also important. When you give away your entire wealth to make the world a better place, you want to ensure that you get maximum bang for the buck. The learning from Buffett, again, is to concentrate. Pretty much like his approach to stocks, Buffett’s philosophy is not to spread the pool across too many causes. Accordingly, Pabrai and his wife chose to focus on education — and how.

Having tossed around ideas relating to microlending and boarding schools for impoverished children in India, Pabrai finally zeroed in on Anand Kumar, who coaches poor students in Bihar to crack the IIT entrance exam. “I estimated that by spending $4,000 per student, we could boost each student’s lifetime income by an average of $158,000. And remember, a dollar buys four times as much in India as in the US.” While Kumar personally didn’t want to scale up his program, he was willing to offer advice on replicating his program — a perfect solution for Pabrai.

Now, in partnership with the Jawahar Navodaya Vidyalayas, the foundation provides two years of IIT JEE prep for about 300-400 students a year. From 2009 to 2012, some 820-odd students have appeared for the IIT entrance exam after coaching through Dakshana — 354 have been accepted, a 43% acceptance rate compared with the national average of 2%. Since 2007, the cost per scholar has come down by more than half, to about $2,000. So far, Pabrai has spent over $5.5 million on his charity; he will continue giving away 2% of his networth every year as long as the networth is over $50 million at the end of each given year. “I care about the fact that every dollar we spend generates greatest possible impact for society. Period. Not how good we feel.”