Growing up, the cramped one-room apartment where she lived with her parents and that doubled as a kitchen was what Pooja called home. The building had just one bathroom, shared by nearly 70 people.

Studying meant crawling under the bed, the only quiet place she could find. Here, in the dim light, she made drawings for her electrical engineering coursework.

“That was the only place where I got peace,” the 41-year-old techie recalls.

In 2005, Pooja received her diploma. Her first job was as a coder in Gurgaon, with a salary of Rs 7,056 a month. Step by step, she climbed the corporate ladder. Today, she works at Tata Consultancy Services (TCS) and earns Rs 35 lakh a year.

The IT sector in India has for decades been the golden ticket for millions like Pooja, a sure-shot entry to the country’s middle class.

“This surge in employment has provided numerous high-skilled job opportunities, contributing to the rapid growth of India’s middle class,” says Rituparna Chakraborty, co-founder of staffing firm TeamLease.

Several factors were behind the IT boom. The economic liberalisation of 1991 opened India to global markets, attracting multinational tech giants such as Intel, Cisco, Accenture and Microsoft, which set up operations in India. Amid global apprehension over the ‘Y2K bug’ at the turn of the millennium, companies in the US and Europe sought out skilled software engineers in India to mitigate the technical glitch. It was a watershed moment for the sector.

Over the next two decades, the industry’s revenue vaulted from $5.9bn in 2001 to an estimated $245bn in 2023. The expansion led to direct employment in the sector crossing 5mn a couple of years ago, according to Chakraborty.

Disruption is Brewing

On a regular workday in February, Rohan (name changed), a recent graduate who had joined the multinational tech company Infosys, had a meeting scheduled for 2.30 pm. When he arrived, he found himself in a group of 50 employees. By 5 pm, they were all out of jobs.

Infosys terminated around 400 trainees on its Mysuru campus that day, citing failure to clear internal assessments. The trainees had waited two years for their date of joining. Their first job ended before it could begin.

“The HR raised her voice and told me to sign the document,” Rohan recalls. “I hesitated, but she said if I didn’t, my profile would be blacklisted.”

Stories like Rohan’s are no longer rare. Major IT services companies such as Wipro, HCL Technologies and Tech Mahindra have all delayed or rescinded job offers. The industry that once promised stability is now grappling with uncertainty.

The wave of layoffs in the sector—driven by the growing adoption of AI tools and its consequent automation of tasks—has led to an unprecedented job crisis among young graduates and tech employees.

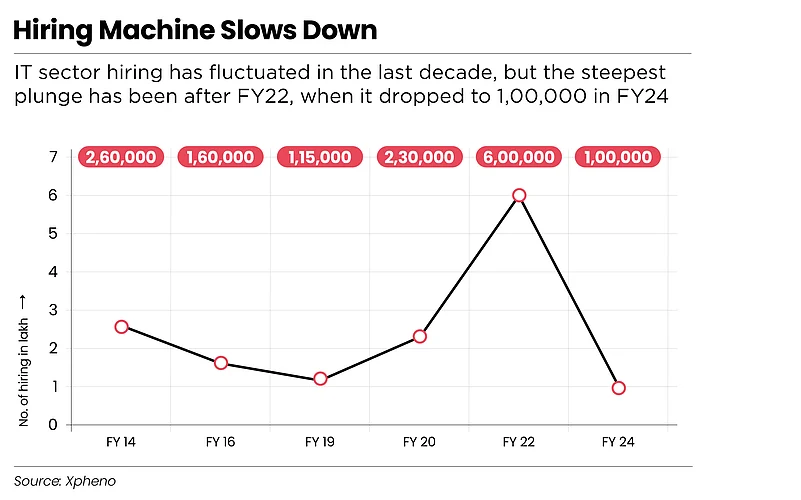

This seismic shift is evident in hiring numbers. Hiring dropped to 95,000 in financial years 2018 and 2021, followed by a sharp rise in 2022, likely on account of pandemic-led digitalisation. But the momentum did not sustain, and in 2023, this number fell to 2,50,000. It further declined to 1,00,000 in 2024, shows data from staffing-platform Xpheno.

Compounding jobseekers’ woes, salaries at IT companies have stagnated. According to TeamLease data, the lower bracket of an average entry-level salary in IT was Rs 3.5 lakh in 2015. In 2024, that number has inched up to Rs 3.8 lakh.

But the conversation about AI’s impact on jobs isn’t new. Automation has long been a spectre looming over the workforce, but generative AI is accelerating the shift. As AI tools reshape the job market, take over repetitive IT roles, companies are being forced to rethink their workplace strategies. And often, this means employees bear the brunt.

Experts say the reason why these companies previously hired in large numbers is not technology but the structure of their businesses. This means that headcount is connected to billings. For example, a project may be billed as 30 ‘resources’—in industry parlance—multiplied by the per hour charge.

But setting this aside, the technological work carried out by those at the lower ranks—maintenance and patching legacy systems for large clients—could also be done by generative AI coding. And logically, this should be the easiest to replace.

There is growing consensus that AI will, indeed, lead to fewer opportunities as some routine and rules-based roles get automated. Already, tools such as GitHub Copilot and OpenAI Codex are writing and debugging software. The work that once required a team of junior developers can now be done in minutes.

Pramod Bhasin, founder of IT-services firm Genpact, estimates that AI could automate 20–30% of low-level jobs in the near future. Call centres, sales roles, software testing—entire categories of employment are shifting. However, he highlights that every technological shift—from e-commerce to automation—has sparked similar concerns. While some jobs will be affected, AI will ultimately enhance productivity rather than destroy industries, he says.

Sanjeev Bikhchandani, co-founder of online-classifieds company Info Edge, takes a more measured approach: “The situation should be monitored closely to understand how AI-driven changes unfold in the Indian job market.”

But for many young IT workers, that eventuality is already here.

“I’ve lost faith in IT. With AI advancing, jobs are shrinking. It’s safer to have a backup, so I’m preparing for government exams,” says Rohan, when asked about his plans.

Reinvent or Perish

India’s IT sector was built on a cost-arbitrage model, that is, it profited from the cost disparity in services between different markets. But AI is changing the game. Tasks once outsourced—coding, customer support, data processing—can now be automated. Companies no longer need a workforce of young graduates to handle routine tasks.

Trainees or young recruits in DevOps—a software engineering approach that integrates development and operations teams—and cloud roles earn Rs 80,000 to Rs 1 lakh per month, according to Abhinav Gupta, founder of AI start-up DEPX. AI tools that replace them cost just Rs 30,000 to Rs 40,000 a month.

This shift presents an existential challenge. If India’s IT sector is to survive, it must move from cost-based competition to value-based differentiation.

Placement coordinators say that IT companies are more selective and recruit based on specific skills, and also look for expertise in technologies such as cloud computing

“Indian IT majors need to incubate product delivery separately from their current traditional services models as the product pricing model will cannibalise their existing businesses. Some of them are making tentative plans to do this, but I’m yet to see any of them address this aggressively. The shift to ‘services-as-software’ is going to disrupt traditional Indian IT firms and they need to be ahead of the curve to exploit the opportunity,” says Phil Fersht, chief executive of global advisory firm HFS Research.

There’s a problem: Indian IT firms are not investing enough in R&D. In financial year 2024, TCS was the frontrunner, spending 1.1% of its revenue on R&D. Tech Mahindra was the lowest with a meagre 0.03%.

Globally, India’s private sector lags in R&D compared to peers in China and the US. The private sector’s contribution in India accounts for only 36.4% of the nation’s gross expenditure on R&D. Contrast this with China, where the private sector contributes 77% and in the US, 75%.

The other hurdle is IT giants’ reluctance to use AI solutions developed by start-ups. Instead, there is a tendency to build everything in-house, which slows them down, say industry sources.

And even when companies build AI solutions, they are often outdated within months because specialised start-ups iterate and improve their solutions much faster.

For India to stay relevant in the global tech race, IT majors need to do more. This means that companies must train their workforce in AI and emerging technologies. And that requires a serious rethink of India’s education system.

The Skills Crisis

In 2019, the World Economic Forum warned that a growing skill gap threatened India’s technological progress. In 2022, a Nasscom report estimated that by 2025, nearly half of India’s tech workforce would need to reskill to meet industry demands.

The Economic Survey 2025, however, is more cautious about the danger AI poses for employment. Chief Economic Adviser V Anantha Nageswaran said in January 2025, “Deployment of AI presents both opportunities and challenges. We all feel that technology eventually displaces more jobs than it is created. But the key word here is eventually. What happens between now and eventually is critical.”

Employers in the sector are already giving preference to specific skills in job-seeking graduates.

Placement coordinators note that recruiters prioritise skills in areas such as full-stack development, which involves both front-end and back-end programming, as well as cloud computing, which enables businesses to manage data and services through platforms like Azure and Google Cloud.

Nagesh P Dayanand Sagar, director, training and placements at Dhananthakar College of Engineering in Bengaluru, says that previously, companies only focused on a few criteria.

“Now, the process includes multiple stages: pre-placement talks, online tests [focused on coding, technical MCQs and English], optional group discussions, technical interviews, managerial rounds and HR rounds,” says Sagar.

Candidates are also expected to know how to use AI tools such as GitHub Copilot and ChatGPT. While these generate code, jobseekers must understand how to integrate and customise them within applications.

But students who recently graduated or are enrolled in engineering courses say they are taught little about AI. “You’ll need to learn a lot on your own. Resources from YouTube, online tutorials and projects can help build practical knowledge in AI,” says Arya (name changed), a third-year IT student who uses YouTube to learn AI skills.

The alternative is to be left behind. The IT dream had once seemed invincible. But dreams, like industries, evolve. The sector’s contribution to India’s economic output jumped from 0.4% in 1992 to approximately 8% in the last decade. Its ability to rake in dollars has been one of the most important reasons why the country’s current-account deficit has remained under control despite a growing import bill.

The question is no longer if IT will survive AI—but whether it can redefine itself before it is too late.