A few months ago, Suresh K (name changed on request) bought a one-way ticket to the US, joining the quiet exodus of young Indians chasing a future their homeland could not provide. At 27, with over two years of experience at a personal finance start-up in India, Suresh has already mapped out his trajectory: a master’s degree in AI from North Carolina State University, followed by—if all goes to plan—a career in the kind of frontier technologies that shape the modern world.

For Suresh, the decision was almost inevitable. The US has long been a gravitational force for the ambitious, a place where talent is rewarded. He has no illusions about returning home. “India would have to outbid America,” he says, matter-of-factly—not just in wages, but in the very architecture of career growth, in its ability to nurture research, innovation and technological ambition.

India’s intellectual capital is, arguably, its most valuable export. Yet why does it continue to be shipped abroad? Arvind Virmani, member of NITI Aayog and a former chief economic adviser (CEA), offers a blunt diagnosis: “Independent India never built its talent pyramid from the ground up. Instead, we started at the top, investing in elite institutions while neglecting primary and secondary education.” The result is a paradox—a country that produces world-class minds but struggles to retain them.

Leaving on a Jet Plane

By late 2024, Indian-origin executives led 25 of America’s 500 largest companies, more than doubling from just 11 in the early 2010s. The likes of Satya Nadella at Microsoft, Sundar Pichai at Google and Shantanu Narayen at Adobe have become symbols of Indian excellence. Their success is often framed as a point of pride for India, yet there is a deeper unease. These leaders built empires, not in Bengaluru or Hyderabad, but in Silicon Valley.

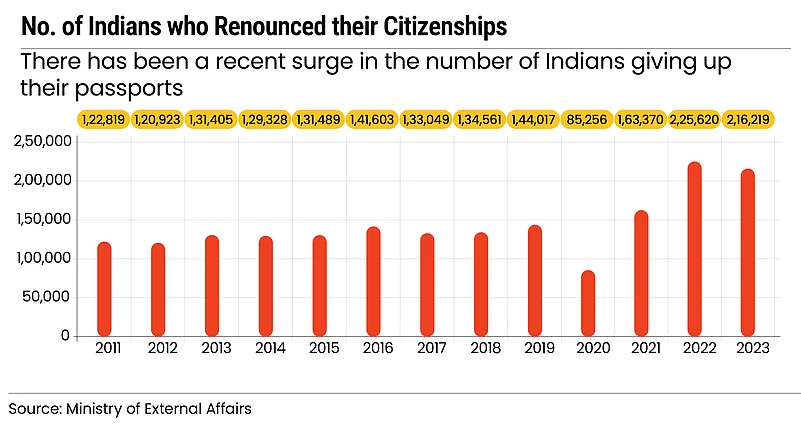

Increasingly, Indian citizenship is not an identity but a choice—one that many are choosing to forgo. According to the Ministry of External Affairs, a record 2,25,620 Indians renounced their nationality in 2022, a sharp rise from 1,63,370 the year before. Even in 2020, when the pandemic froze much of the world’s movement, 85,256 Indians still relinquished their passports. A decade ago, these figures hovered around 1,20,000 annually.

The marquee names make headlines, but the more sobering reality is the quiet exodus of India’s vast science, technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM) workforce. They are not just leaving, they are being actively courted; their ambitions funded and their talents rewarded elsewhere. What India risks losing is not just its best and brightest, but the very minds that could define its technological and economic future.

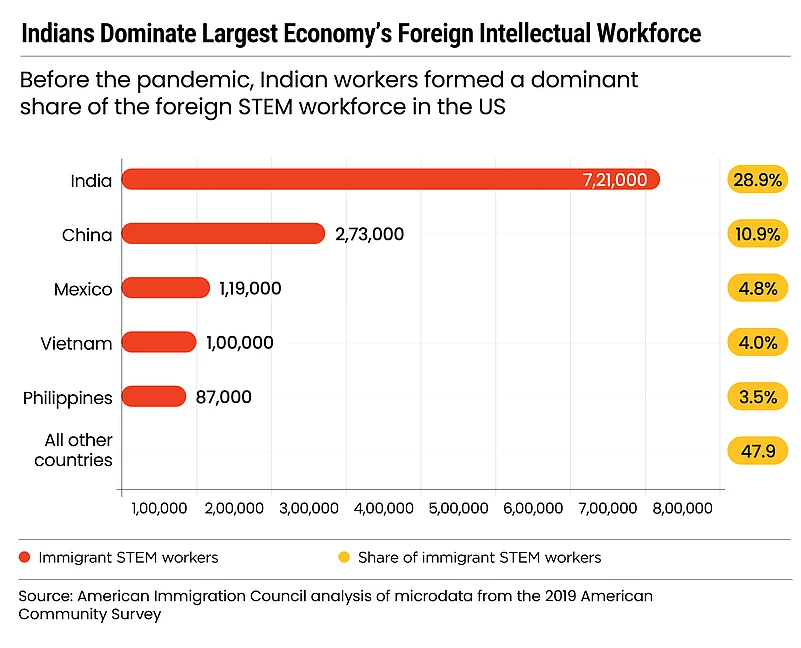

The world’s largest economy thrives on ideas, and many of those ideas come from elsewhere. In the US, immigrants are responsible for nearly a quarter of all patents filed, and a significant share of that intellectual horsepower comes from India. A year before the pandemic, Indian immigrants accounted for 29% of all foreign STEM workers in the country, according to the American Community Survey.

But Indian immigrants in the US aren’t just abundant; they are dominant. A study by the Migration Policy Institute, a Washington, DC-based think tank, found that, on average, Indian migrants out-earn and out-educate both other immigrant groups and native-born Americans. In 2021, Indian-led households reported a median annual income of $150,000—more than double the national median of $70,000.

Michael M Crow, president of Arizona State University, says that with India and the US both being democracies, the two nations allow for a free flow of people, ideas and intellectual property. “We are at the beginning of what is likely to be a more comprehensive relationship between the US and India,” he says.

Crow expects the flow of Indian talent to go up further given “the historical ability of Indians in maths, creativity and conceptual areas”. This outflow of human capital will hurt India.

The New Wooers

Much like the US, Europe, too, has turned its gaze eastward, courting Indian talent to plug gaps in its workforce. The continent’s ageing demographics and increasing demand for tech expertise have made Indian professionals a sought-after commodity. A study examining the economic contribution of Indian migrants to the European Union (EU), using the Netherlands as a case study, highlights their growing presence.

“They bring skills and experience and contribute to the economy, especially in IT and through taxes,” the study noted. But beyond numbers, Indian professionals are quietly reshaping industries, filling roles once considered hard to staff. From software engineering to pharmaceuticals, their expertise is no longer an exception in Europe.

Governments worldwide are engaged in a quiet but deliberate competition, each vying for a share of India’s most valuable export. Nowhere is this more evident than in the United Arab Emirates, where Indian businesses—ranging from small and medium enterprises (SMEs) to tech-driven start-ups—are not just welcomed but actively pursued.

By early 2024, more than 62,800 Indian companies were registered as active members of the Dubai Chamber of Commerce, a staggering 30% increase in just a year. And the momentum shows no signs of slowing. In the first three months of this fiscal year alone, 4,351 new Indian firms set up shop in Dubai—outpacing every other nationality.

Dubai’s approach is pragmatic, bordering on aggressive. “We have a lot of Indian SMEs and some large Indian companies that started as SMEs, which again reflects the priority given to this proportion,” says Mohammad Ali Rashed Lootah, president and CEO of Dubai Chambers. “All the services we offer—especially under the Dubai Chamber of Digital Economy—are designed to support tech start-ups. We do not limit it to particular sectors as we do not want to miss any opportunities.”

Taiwan, locked in an investment race with India to court Western capital, has made its move. In a bid to bolster its workforce and sharpen its technological edge, it has rolled out two new visa programmes designed specifically to attract skilled Indian professionals. The sectors in focus—technology, engineering and beyond—mirror the very industries that India wants to dominate.

Taiwan’s entry into the fray signals something deeper. It is recognition that India’s talent pool is not just an asset but a resource that, if properly harnessed, can tilt the balance of global economic power. According to the Economic Survey 2024–25, India alone accounts for more than a quarter of the global STEM workforce and 23% of the world’s software engineering talent.

Indians leaving India is hardly a new story. Migration—whether for education, employment, or the ever-elusive promise of a better life—has been a defining feature of the nation’s modern economic history. And while the talent drain is often lamented, it is not without its dividends. What India loses in skilled minds, it gains—at least in part—in money.

For decades, remittances have been an economic constant, a steady pulse of financial support sent home by the country’s vast and far-flung diaspora. In 2023, according to the World Bank, these inflows accounted for 3.4% of India’s GDP, a figure that shows the weight of this external economic engine. With a few exceptions, India has led the world in remittance receipts since the turn of the millennium.

But today, the script is changing—or at least, the ambition is. India no longer wants to play catch-up; it wants to lead. In technology, energy, and beyond, the country is setting its sights on the frontiers of innovation, framing itself as a nation on the cusp of a significant transformation. By 2047, the centenary of its independence, India aims to join the ranks of developed nations.

For that, it needs more than capital. It needs brains.

“True we have not fully supported our innovators to the extent that we should; but there is a positive side too,” says S Krishnan, secretary, Ministry of Electronics and Information Technology, alluding to the fact that many of the people who migrate also over time nurture and mentor our young brains.

Lessons From the Dragon

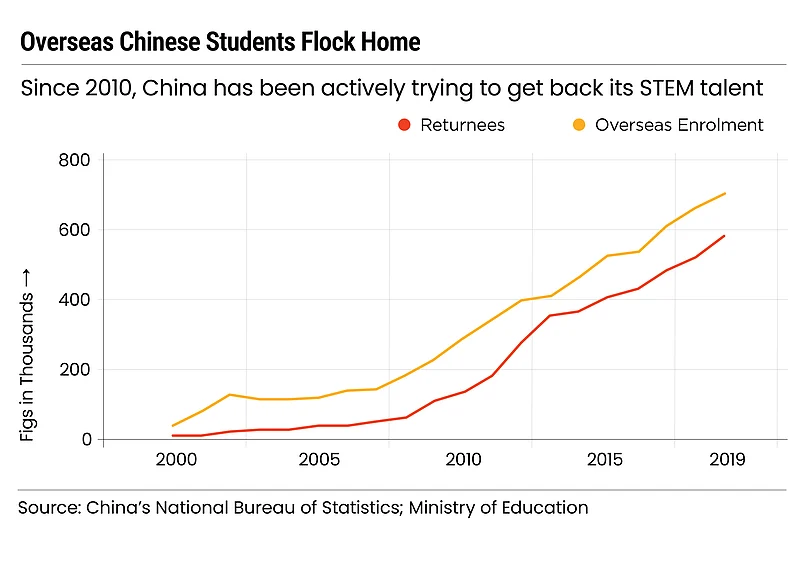

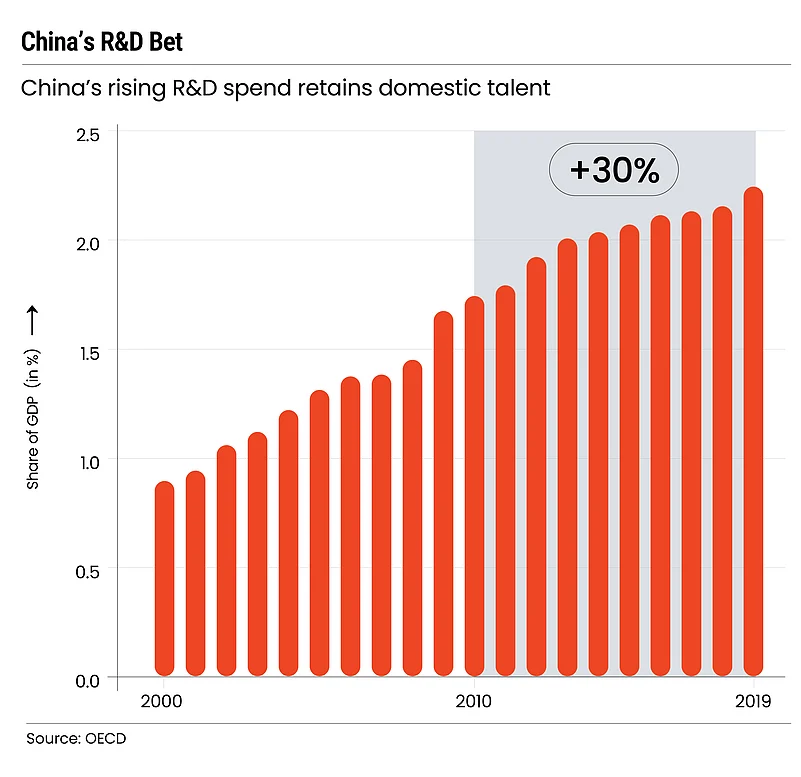

Like India China too has been a steady supplier of STEM talent to the West. But now it wants its brightest minds back. Beijing has launched more than 200 talent-recruitment programmes since 2010. Among them, the Thousand Talents Programme and its youth-focused counterpart, the Young Thousand Talents (YTT) initiative, stand out as aggressive, well-funded attempts to staunch China’s intellectual drain.

Since 2015, the number of overseas-educated Chinese professionals returning home has steadily climbed, spiking by 34% in 2020 alone. These returnees are not just any job seekers—nearly three-quarters hold a master’s degree, making them precisely the kind of talent that fuels high-end research and innovation.

China’s investment is yielding results. Once perceived as a follower in technological advancements, the country now competes head-to-head with the US in AI and emerging technologies. Its latest AI model, DeepSeek, is a direct challenge to OpenAI’s ChatGPT, signalling Beijing’s intent to carve out a dominant position in the global tech race.

The broader lesson is that the most talented minds—whether in AI, biotechnology or deep tech—thrive in ecosystems that reward long-term investment in ideas. Those researchers who returned excelled precisely because they found institutional backing to sustain their research, publishing 27% more than their overseas peers who stayed back, according to the Stanford Centre on China’s Economy and Institutions.

On the other hand, India does not have a single university in the top 100 globally, yet it aims to compete with China in technology, Raghuram Rajan, who had held both the posts of RBI governor and CEA, told Outlook Business in a recent interview. “We need to invest in building stronger engineering colleges, scientific labs and establishments that could equip us with the technology to participate in a broader range of areas, including AI and chip design,” he argued.

Veezhinathan Kamakoti, director, IIT Madras, agrees with Rajan. “We need the research infrastructure and the manpower. There is a lot of equipment that none of the institutions have access to. It is also a chicken-and-egg situation sometimes. If you have those equipment, people who could use those equipment will join. As I don’t have people who can use these equipment, I don’t buy these equipment,” he told Outlook Business recently.

Drop in the Ocean

Even for all its ambitions, India’s R&D spending remains a fraction of its global competitors. The country’s gross expenditure on R&D more than doubled from Rs 60,196 crore in 2010–11 to Rs 1,27,381 crore in 2020–21, according to the Economic Survey. Yet, as a share of GDP, it remains a mere 0.64%. The result? A pipeline of talent that, despite its immense potential, often sees its best opportunities materialise elsewhere.

Take Suresh (and a host of others, see case studies), for instance. Convinced that India will never match the opportunities available in the AI space in the US, his decision to leave is not just personal—it reflects a broader reality. While India aspires to become an upper-middle-income country by 2030 and a high-income one by 2050, that trajectory hinges on significantly ramping up R&D investment.

The challenge isn’t just the size of the investment but who is making it. In leading economies like the US, China, Japan and South Korea, private enterprises account for more than 70% of total R&D spending. In India, however, the burden falls largely on the government.

While annual public spending on science and technology has grown—from under Rs 100 crore in the past to Rs 20,096 crore today—private sector investment remains tepid.

The government hopes to change that by inviting private enterprises into the fold. In such a bid, the Centre has set aside a corpus in this year’s Budget to nudge India Inc into investing in R&D.

“This funding will be used in collaboration with the private sector, with R&D projects from both government and private sectors being eligible for funding,” says Manoj Govil, secretary of expenditure, Ministry of Finance. But whether Indian companies, long averse to the risks of deep tech and fundamental research, will take the bait remains to be seen.

Because one of the core issues is the lack of risk-taking behaviour among Indian companies, points out IT secretary Krishnan. V Anantha Nageswaran, the present CEA, meanwhile, sees a lack of long-term thinking. “The changing context calls for strengthening domestic R&D, viewing it as an investment rather than an expenditure,” he says.

Policymakers are urging the private sector to wake up to the changing global order. For decades, brain drain meant Indian engineers, scientists and programmers boarding flights to Silicon Valley, Wall Street or research labs in Europe and never looking back.

But in recent years, the nature of brain drain has mutated. It is happening in our backyards; in cities such as Bengaluru, Hyderabad and Gurgaon, where some of the brightest Indian professionals work—not for India, but for the vast multinational corporations that have set up shop in the country.

This new pipeline of talent export runs through global capability centres (GCCs)—offices established by global firms to handle everything from financial analytics to AI research. India now hosts over 1,700 such centres, employing nearly 1.9mn professionals. By 2030, that number is expected to rise to 2,100–2,200 centres, with a workforce of up to 2.8mn. What started as an outsourcing experiment has turned into a sophisticated model where global corporations tap into India’s vast talent pool without requiring relocation.

Nageswaran believes it is time for India’s private sector and academia to step up, breaking their long-standing reliance on government-led research funding. For India to truly compete on the global stage, he argues that industry, academia and the state must come together. Their collaboration will not just increase the scope for innovation but also address pressing quality of life issues, he says.

Quality of life matters, notes Comrise, a US-based IT and engineering staffing and consulting partner. China’s intellectual workforce is not solely returning for superior opportunities. They are returning also for a better environment, and a sense of belonging, among other things.

Pursuit of Happiness

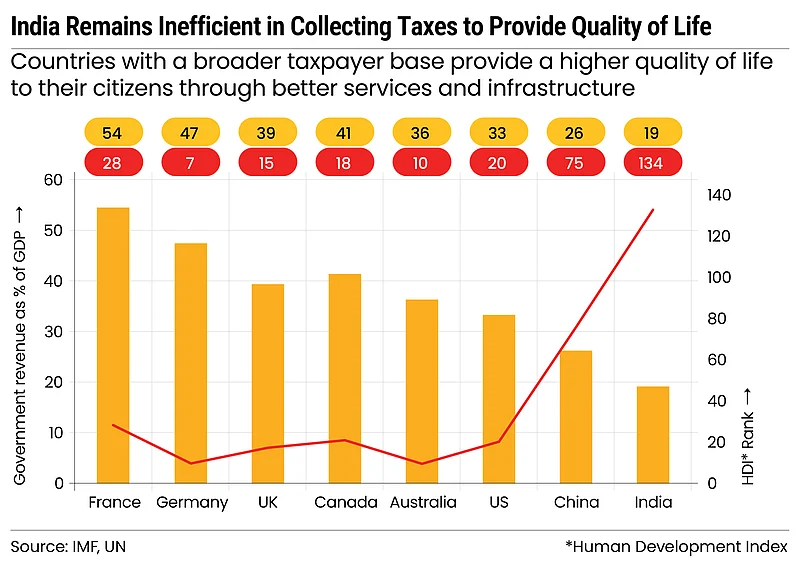

Migration, once dictated by economic opportunity alone, is now also shaped just as much by health care, safety and environmental quality. The UN estimates that 281mn people worldwide relocate in search of better living conditions. Yet, India remains an unlikely destination. Its ranking of 134 on the Human Development Index reveals a country struggling with the basics—air quality, poor infrastructure and overall quality of life. These aren’t just inconveniences; they’re silent forces pushing talent elsewhere.

India’s tax rates, especially for top earners, often invite scrutiny. But the frustration isn’t about taxation itself; it’s about the gap between what people pay and the public services they receive. High-salaried individuals are happy to pay the same taxes in the US. In fact, India’s tax revenue as a percentage of the GDP emerges as a bigger issue here, ranking significantly lower than countries that perform better in terms of giving a quality of life to its citizens. In other words, the talented are punished in India at the cost of evaders.

Krishnamurthy Subramanian, former CEA and India’s executive director at the International Monetary Fund (IMF), sees the country’s quality of life as an overlooked yet critical factor in its talent equation.

“India should work on enhancing its quality of life by reducing air pollution, water pollution and travel time in metro cities, among other things. This is an area where especially the state governments must work to ensure urban living conditions improve,” he had told Outlook Business in an earlier interview.

Till now, the Centre has been hand-holding the state governments towards quality spending and to justify the tax rates in India. “The Centre is actively working with states, ensuring that capex [capital expenditure] and reforms go hand in hand,” says Tuhin Kanta Pandey, finance secretary and secretary of revenue, Ministry of Finance.

But the time has come when states take self-initiative. “The Budget expects state governments to provide similar support. Currently, all state governments combined have a capex level of about 2.5% of GDP. From 2.5%, can it become 3%? Similarly, can the quality of the expenditure improve?” asks Ajay Seth, secretary, department of economic affairs.

Regular passing-the-buck exercises between the Centre and various state governments over issues such as stubble burning, river-water sharing and urban waste management have exacerbated matters. And with it the quality of life has nosedived.

Pick Our Brains

George Santayana, the Spanish American philosopher, had famously said, “Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it.” India needs to remember its history as well. Before independence, India was not just a colony; it was a financial reservoir that Britan depleted, exporting raw materials while offering little in return. In the late 19th century, Dadabhai Naoroji, one of the founders of the Congress party, contained this exploitation in what came to be known as the “drain theory”.

The developed world, today, no longer ships India’s cotton and spices, instead it takes something far more valuable. And it does so without entering the borders of the country. Across research labs, tech start-ups and economic hubs, the best Indian minds are designing the future, but not for India.

The drain must end, not with rhetoric, but with a decisive commitment to ensure that the best minds in India don’t just “Make in India” but “Make in India for India.”

With inputs from Tarunya Sanjay