In May 2022 there was a palpable sense of excitement in India’s business ecosystem. The country had breached the mark of 100 unicorns—a record only held by the US and China.

“This is a matter of pride for every Indian,” Prime Minister Narendra Modi soon declared in his Mann ki Baat address.

But that was just meant to be the starting point. In the subsequent months, top officials set a bigger goal—they wanted India’s hinterlands to give birth to start-ups valued at over $1bn. For instance, Union minister Ashwini Vaishnaw said that the prime minister's vision was that “unicorns should also be built from the villages of India”.

As entrepreneurs from Tier-II and III geographies emerged in reality shows like Shark Tank, it seemed as though that dream was not beyond possibility. States doubled down on creating start-up schemes. Venture-capital (VC) firms went out to Bharat to scout for the next big billion-dollar idea. Government figures and industry reports showed thousands of start-ups taking root in smaller cities and towns.

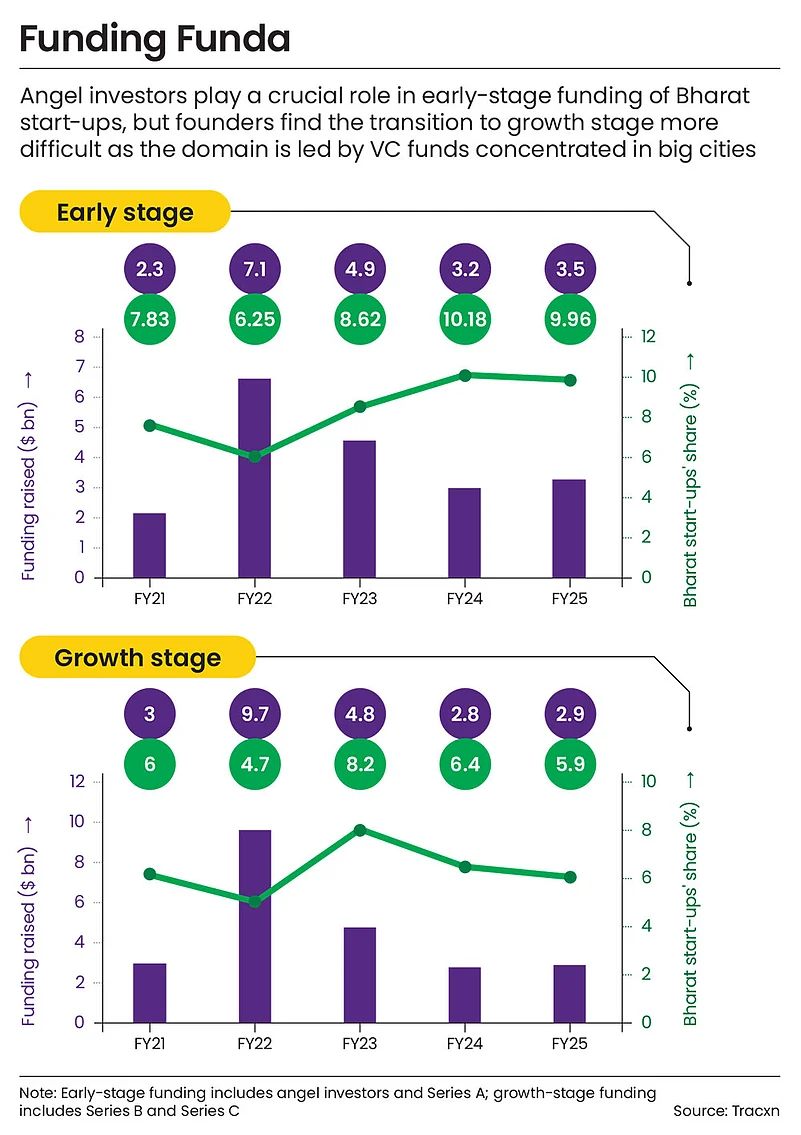

Yet, a closer look at the numbers throws up a sobering reality. While hundreds of start-ups are receiving early-stage funding in Tier-II and -III geographies, they are not finding the growth capital to scale up into large businesses that can help them sell their goods and services nationally and internationally.

Out of the 584 growth-stage start-ups evaluated for Outlook Business’ Outperformers’ ranking, only 36 were Bharat start-ups, that is, start-ups based in Tier-II and smaller cities. This means only 6.16% of India’s growth-stage start-ups are based in locations other than Tier-I cities like Bengaluru, Gurgaon and Mumbai.

“Capital, competent talent and culture are the bedrock of a strong start-up ecosystem. And all of these are better available for India start-ups than Bharat start-ups,” says Suraj Malik, founder and chief executive of Legacy Growth, a wealth-management firm.

Still Out of Sight

A limited number of investors in smaller cities and low visibility among investor circles in metros demand extra efforts from Bharat start-ups to take the very first step of their growth story, that is, capital. This skews the representation of Bharat start-ups, particularly in the growth stage.

For Kochi-based Kannappa Palaniappan P, founder of underwater robotics start-up EyeROV, operating without investor money was not an option. Being a deep-tech firm, it needed capital to develop R&D facilities, source high-end equipment and build systems that match military-grade standards.

“Being in a niche space and a Tier-II city made it difficult initially. We had to travel frequently to Bengaluru to attend investor events and conclaves to present ourselves,” Palaniappan says. After almost three years since its foundation, EyeROV raised funding in 2019.

According to Tracxn, a data platform, out of the total funding of $2.9bn in the growth stage (Series B and Series C) during the last financial year, only 5.9% of it went to Bharat start-ups. The share has remained almost the same as was in 2020–21 at 6%.

“Today, most VC firms are headquartered in Bengaluru. Even funds that originally started in Mumbai have largely shifted operations there,” says Anil Joshi, founder and managing partner at Unicorn India Ventures, a VC firm.

When deal flow is concentrated within a few neighbourhoods, naturally the density of investments increases, he says. Unicorn India is one of the investors in EyeROV.

Talent Crunch

Lack of talent availability in smaller cities remains another obstacle. As one Bharat start-up founder puts it, they try to be “chief everything officer” in the initial years.

After a certain point in a start-up’s journey, finding domain experts becomes inevitable, a demand which the smaller cities are struggling to meet currently. Those working in metros do not find it worth going to a small town. On the other hand, the human resource available locally do not possess the required skills.

Precisely for this reason, 35-year-old Alok Katiyar delayed developing an app for his start-up WeClinic. The Kanpur-based start-up delivers homeopathic medicines to patients.

In a fast-paced start-up ecosystem, scaling quickly is critical to securing first-mover advantage. Rapid growth is essential

It has been five years since WeClinic’s user interface has essentially been the company’s WhatsApp account. He has a team of 200 people in Kanpur who are largely involved in sales and tele-calling.

The plan to build an app for his business is still a work in progress. An app would demand developers, and he is unable to find people for that in Kanpur. “Everyone wants to go to big cities,” he says.

Though Kanpur boasts of institutes like IIT and Harcourt Butler Technical University, neither the city nor the salary he can offer attracts people from these top institutes.

“Tier-II cities don’t limit growth up to a point. But at certain stages, or for specific sectors, start-ups may need to move part of their operations closer to specialised ecosystems,” says Joshi of Unicorn India Ventures.

Survival Strategy

Metros like Bengaluru and Gurgaon have mature start-up ecosystems, with many peer companies to learn from, which shortens the learning curve, investors point out. In smaller cities, that learning curve tends to be slightly longer.

That is where the priorities of the investors and the founders start to diverge. While investors seek returns on their investment at the earliest, start-ups want patient capital to grow at their own pace.

For this very reason, Nengneithem Hengna, founder and chief executive of eco-fashion start-up Runway Nagaland, declined investment offers from various VCs. Bank loans have been her go-to source of capital. “We are aware of our limitations. The start-up ecosystem here [in the Northeast] is in its nascent stage. We cannot commit huge returns to VCs,” she says.

Limited funding avenues prompt Bharat start-ups to focus on unit economics at an early stage instead of burning cash like their India counterparts, a reality acknowledged by both investors and founders. For many founders, this discipline is a matter of pride.

According to Tracxn, the average loss of top-five Bharat start-ups (at $34,605) was only a fraction of the average loss of Metro start-ups (at $15mn) between 2020–21 and 2023–24.

“When capital is available more easily, you often rise early and fall off early. That churn can hurt in the long run,” says Nikhil Doda, co-founder of Archian Foods. The Fatehgarh Sahib-based company sells carbonated drink Lahori Zeera.

For the first four years of its operations, the company raised no external funding, Doda says, acknowledging that the journey could have been different with better access to investors.

But this survival strategy is a trade off with quick growth. While Bharat start-ups have better profitability, India start-ups are far ahead in scaling rapidly. From 2020–21 to 2023–24, the average revenue of Metro start-up was at $44.16mn, 12% higher than that of a Bharat start-up ($39.14mn).

Slow growth runs counter to the very logic of being in the growth stage, investors say. In a fast-paced start-up ecosystem, scaling quickly is critical to securing first-mover advantage, as multiple start-ups are often working on similar ideas. Rapid growth, therefore, becomes essential to capturing market share.

“That [scaling] becomes a challenge [for Bharat start-ups],” says Sudhir Dash, founder and chief executive of Unaprime Investment Advisors. “Would you rather operate from Bengaluru and manage growth effectively, or operate from a smaller city and struggle with scale? That is the dilemma founders must consider,” he says.

Long Road Ahead

The prime minister’s objective of growing the start-up ecosystem in non-metro cities is not misplaced. However, the maturity of this ecosystem remains far from satisfactory, as reflected in stark geographical disparities.

In his column for last year’s Outlook Business start-up edition, Sanjiv Singh, joint secretary, Department for Promotion of Industry and Internal Trade (DPIIT), noted that around 50% of start-ups recognised by the DPIIT came from non-metro regions, playing a crucial role in positioning India among the world’s largest start-up ecosystems.

If India is to become a developed country, uniform growth will be central to that goal, something that is going to be a long and arduous task to achieve.