On a December morning in Nashik, as Ajay Vedmutha walks across the factory floor of Bedmutha Industries, he only has one question on his mind: “Are we prepared to be able to sell in Europe from next month?”

A steel- and copper-products manufacturer, Vedmutha is bracing for the impact of the European Union’s (EU’s) carbon tax. Vedmutha has spent over a decade turning his plant green. And now, even though it runs on renewable power and boasts a lower carbon footprint, he still wonders if it’s enough.

However, not everyone is even this close to being prepared.

A few hundred miles away in Raipur, Abhay Parakh, director of Jainam Ferro Alloys, is also turning his medium-sized enterprise green. It’s been a year since he started the process, but clearance paperwork has stacked taller than the production samples on his table. “The Centre wants to push it, but state governments don’t understand the urgency of the situation,” says Parakh.

These two businessmen—one prepared early and one caught in bureaucratic limbo—capture India’s dilemma as the EU’s carbon border adjustment mechanism (CBAM) goes live this month.

What is CBAM?

Europe’s drive to cut greenhouse gas emissions by 55% by 2030 is triggering a sweeping overhaul of its climate policies. Under the “Fit for 55” package, it is strengthening its emissions trading system (ETS) and launching CBAM.

CBAM is essentially a carbon tax the EU will charge on imported products—like steel—based on how much carbon dioxide (CO₂) was emitted while making them. If a product is made in a country with higher pollution, the EU will charge extra tax at the border to “balance out” the carbon cost.

The goal is to make sure European producers that pay high carbon costs are not undercut by cheaper, high‑carbon imports. Indian steel emits about 2.5 tonnes CO₂ per tonne, approximately 0.7-1.0 tonnes higher than the EU average, making it costlier. At ETS carbon prices of around €80 per tonne, this equates to €55-80 (₹5,200-7,500) added per tonne of Indian steel entering Europe.

This means European buyers will have to pay extra tax, which makes Indian steel less competitive compared to cleaner producers. At the same time, CBAM makes exporting carbon-intensive steel to the EU more expensive. “If we kept carbon prices at ₹8,000 per tonne, our industry would collapse too just like the EU,” says Sangeeta Godbole, a former trade negotiator with Europe.

Here, India’s Carbon Credit Trading Scheme (CCTS), launched in 2023, is relevant. But with domestic carbon prices seen below $10 per tonne of CO₂—a fraction of around €80 in the EU—it is too low and would lead to minimal deduction benefit.

India Impact

The EU has long been a crucial market for Indian metals, particularly steel. India, the world’s second-largest producer, ships two-thirds of steel exports to Europe. Four EU markets—Italy, Belgium, Spain and Poland—account for nearly 40% of Indian steel exports. In aluminium, a quarter of Indian shipments head to Europe. “The impact on India is likely to be more pronounced due to its higher dependency on the EU market for these goods,” notes Associated Chambers of Commerce and Industry of India.

Many European buyers were already skittish when the EU’s “report-only” phase—requiring only emissions data—began in late 2023. Unsurprisingly, Indian steel exports to the bloc fell over 31% between January and August 2025.

European companies have either cut back orders or sought greener suppliers like Türkiye, the US, the UK and South Korea. And when CBAM reporting began, India’s steel and aluminium exports to the EU plunged by about 24.4% in FY25 with steel alone crashing 35.1%, according to a report by Global Trade Research Initiative (GTRI), a think tank.

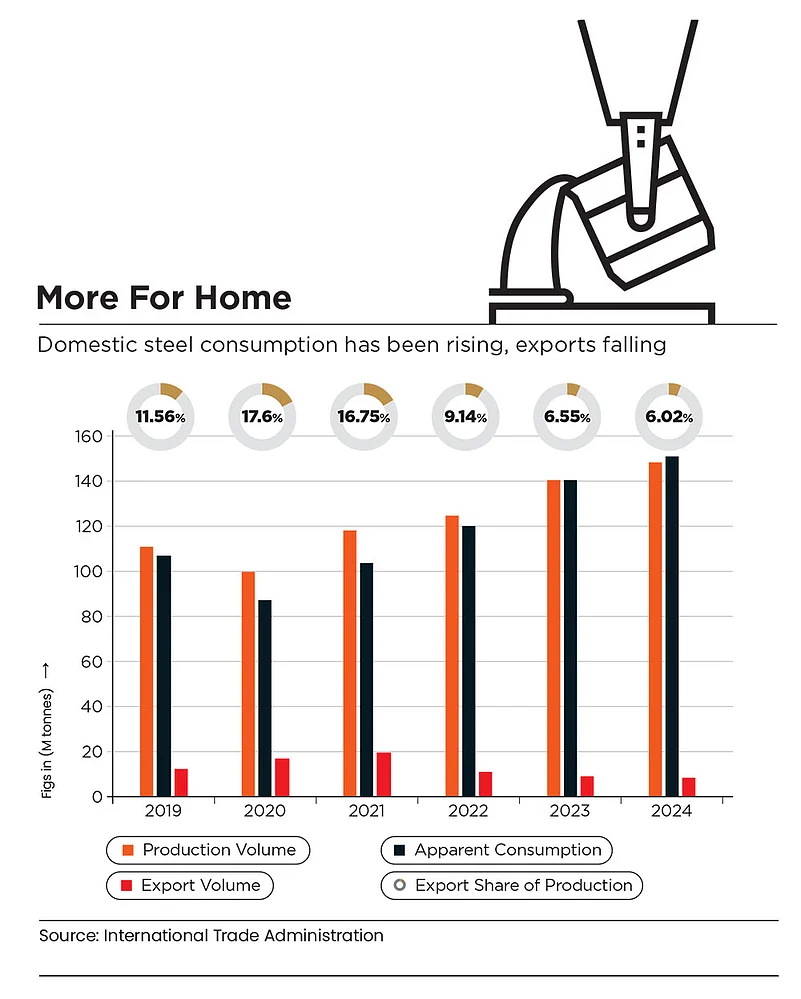

And even though, over the past few years, India has been producing most of the metals for domestic consumption, a developing economy needs to be globally competitive, not just productive. Currently, India exports only 6% of its steel output but has a target of exporting 25mn tonnes by 2047 and growing production capacity to 500mn tonnes.

In fact, to offset EU impact, India is eyeing regions like West Asia, Africa and Latin America. Clearly, exports are central to the government’s roadmap for the sector’s growth.

As of now, CBAM covers iron and steel, aluminium, cement, fertilisers, electricity and hydrogen, together forming around 10% of India’s exports to the EU. India may pay 18% of all CBAM levies, nearly double its share of EU import value, estimates Fastmarkets, a global cross-commodity price reporting agency.

And CBAM is not stopping with Europe. The UK, India’s second-largest steel export destination, is introducing a similar regime by next year. Countries like Australia, Canada, Taiwan and South Korea may soon follow suit. Sanvid Tuljapurkar, sustainable trade law lead at Tulip Consulting, a think tank, sees export pathways shrinking further with these measures.

“Coal will remain central for now, but posing a challenge in CBAM context. So, structural barriers—resources, funding and technology—underpin the problem,” she says.

Back home, however, a divide can be seen when it comes to responding to CBAM. While bigger steel players are sprinting ahead with their deeper pockets, more carbon-intensive smaller units lack the tools to adapt.

Is India Prepared?

Frontrunners like Tata Steel and Hindalco identified early on the impact of carbon border taxes as a key business risk and had the resources to get on the decarbonisation path.

From setting up scrap-based electric arc furnaces (EAFs) to having an in-house carbon price system, bigger players are able to move ahead with compliance. They also have monitoring, reporting and verification (MRV) teams in place. “Most of these steel plants have net-zero targets more advanced than India’s. One of the reasons is to stay competitive. Not just for CBAM, but also to reduce the risk of financial exposure,” Tuljapurkar notes.

Meanwhile, Jindal Steel is exploring opportunities abroad, like Oman, to manufacture green steel at a cost of around $3bn. However, not everyone can go the Jindal Steel way.

Smaller Units, Bigger Hurt

The burden is heavier for MSMEs, which produce around 40% of Indian steel, but don’t have MRV teams, sustainability units or cheap capital.

Banke Bihari Agrawal, general secretary of the Chhattisgarh Steel Re-Rollers Association, who also runs an MSME unit, says, “Small units are running at an investment of as low as ₹2–3 crore. How can they afford a ₹3–4-crore solar plant? They need a bailout package at least,” he adds.

Steel mills, small or large, can also take the much-less-polluted scrap-based EAF route. But India imports about a quarter of its scrap metal requirement as the domestic market is fragmented. So, the growth of EAF is tied to India developing a scrap economy and soon.

What’s Next?

India faces a battle on two fronts—financing a transition while negotiating international rules. Godbole argues that a waiver for small mills is vital to deal with the “protectionist trade barrier raised unilaterally by the EU”. “They had nearly 20 years to adjust. The first five years, they received free allowances. And suddenly we are expected to cope with high carbon prices—it’s impossible,” she adds.

MRV, too, can only help in the short term, notes Tuljapurkar. “The real challenge is emissions reduction. Compliance alone won’t secure market access—decarbonisation will.”

GTRI suggests that India should study transition flexibilities—longer phase-in periods and partial waivers—offered to the US by Brussels, and seek a comparable treatment. India is currently at the most challenging phase of its FTA talks with the EU and CBAM stays a key issue, said a top commerce ministry official recentlly. So, a window of opportunity is still open for New Delhi.

For a better future and a low-carbon one, India needs better terms in trade deals, particularly with the EU, to cushion the impact of CBAM-like regimes. Decarbonisation can no longer be a choice; it’s a new world reality and it’s here to stay.