In early 2017, Mathew Cyriac was in New York to say goodbye to his colleagues at Blackstone. He had spent eleven years at the Mumbai office and it was time to do something on his own. As he reached the private equity giant’s headquarters in Manhattan’s Park Avenue, he was not quite prepared for what was to follow.

A couple of senior officials at Blackstone asked Cyriac, till recently the co-head of the private equity fund’s Indian operations, if he would be keen on buying over two of its assets in India. Understandably, he was taken aback and asked for time to mull over it. A few days later, he was back in India to take stock of his new venture, Florintree Advisors.

Close to 45 days after that meeting in New York, Cyriac said ‘yes’ to Blackstone – he would now acquire Gokaldas Exports, an apparel export company and MTAR Technologies, a precision engineering company. It was in 2007 that the PE fund had invested in both with precious little to show after a decade. It was clear that an exit was the best option.

Between the two, the publicly traded Gokaldas was clearly worse off. Set up by the Bengaluru-based Hinduja group in 1978, it had fallen behind with issues such as revenue stagnation, working capital crunch and rocky relationships with customers. None of that rattled Cyriac and he felt it was an asset that could be turned around, but after a lot of sweat. “I knew that a certain part of the apparel export business would always remain in India. That alone was reason enough to back it,” he says adding, other export hubs such as Bangladesh had come up, but they still lack the strong ecosystem that India has managed to create around this business.

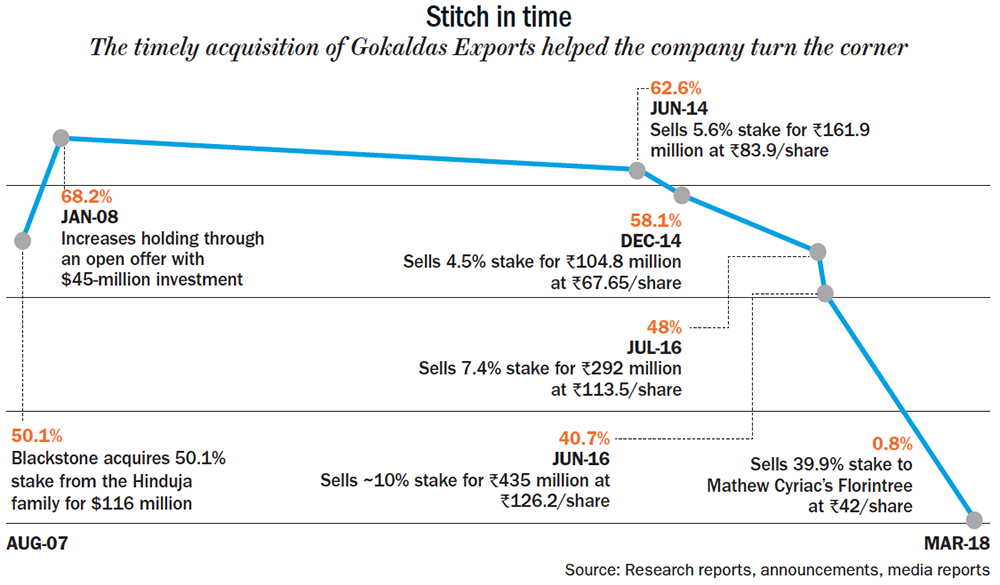

The deal looked mighty attractive – Blackstone had paid Rs.275/share in 2007 for a 70% stake shelling out Rs.6.76 billion. In April 2017, Cyriac’s fund, through Clear Wealth Consultancy, a special purpose vehicle, paid Rs.590 million for a 40% holding at Rs.42 per share (over time, Blackstone had trimmed its holding by selling shares in the market). It was an open secret that the PE major had been looking to sell Gokaldas for a while. Finally, the company had a new owner determined to turn it around (See: Stitch in time).

Stock taking

Once the deal was in the bag, Cyriac called Sivaramakrishnan Ganapathi, a friend and also his classmate from IIM Bangalore. The two men had been buddies on campus and Cyriac wanted him to run Gokaldas. Ganapathi (Siva to those who know him) had been in the Aditya Birla Group for over two decades and as COO, Idea Cellular, had a comfortable job. He had worked across the group in functions such as corporate strategy and also ran Minacs, an IT-ITES company. In his mind, he was now up for a challenge of a different kind.

Luckily for Cyriac, Ganapathi did not need much convincing and in October, he was on board. It has been three years and Ganapathi recalls the initial phase: “Gokaldas was phenomenally challenged and far worse than what I had expected”. It was running on old machines, a broken supply chain that delivered raw materials erratically and absenteeism. Since 2014, the company hadn’t grown its topline significantly, was managing costs inefficiently and was seeing little to no profitability. “It was a pretty scary situation,” he says. While the new management was grappling with internal worries, external ones came visiting.

In 2017, GST was rolled out, which held up working capital. Under the new regime, they had to pay GST upfront and the tax refund would be released after the products were shipped. Secondly, duty drawback — which is an instrument to promote exports, by refunding duties or taxes paid by exporters for goods they have imported, such as raw material — was reduced. This impacted margins by 3% for an industry that already works on low margins. Third, one of the banks providing working capital to Gokaldas was placed under prompt corrective action (PCA) by the RBI, and the central bank reduced the cap of loans the bank could issue. This was during Q3 and Q4 of FY18, the quarters that saw peak production and therefore need the most working capital. Finally, in H2FY18, the rupee started appreciating and weighing on the already negative margin the company was posting. “From here-on, nothing worse can happen,” thought Ganapathi.

He decided to attack the problem from many fronts. First, the management reached out to customers. That exercise turned out to be a reality check for Ganapathi. Travelling across the world (buyers include Columbia, Gap, Zara, H&M, Vero Moda, Puma and Adidas), the feedback he got was uniform – there was no issue on either the product quality or Gokaldas’ talent pool, but what troubled them was very low reliability with respect to time. “That was unacceptable in the fashion business,” he reveals. Of their exports, 70% goes to the US, while 15% and 10% go to Europe and Asia, respectively.

The customers also knew that the supplier was in deep water. “Customers were nervous about how long we would be around and that came in the way of getting more business,” he recalls. So, next in order of business was to get the money needed. In May 2018, Gokaldas raised Rs.700 million through a qualified institutional placement, for Rs.90/share and among those who participated were L&T Mutual Fund and HSF Mauritius.

The management also decided to pursue growth aggressively. “If there was potential in the market, we had to sell more. Cutting costs was not the answer and we just needed to focus on improving productivity,” recalls Ganapathi. But the big challenge was doing it across its 20 factories in the proximity of Bengaluru.

They tackled the supply chain first. Only 54% of the raw material was being delivered on time. “Obviously, it had to be 100% and for that we needed to get the tracking system to function better,” he says. They started tracking orders on a daily basis, having clear timelines on when something had to be delivered and quickly taking corrective action if delays were reported. A year later, 90% of the material was being delivered on time. In the process, output increased 14% without increasing the labour force. The estimate is that it also saved at least 1.5% by way of wastage.

Amit Gugnani, senior vice-president, Technopak, says, “In apparel manufacturing, a company needs to be efficient at all times and that starts from how well they are procuring raw material, the cost at which apparels are produced and a very robust supply chain.”

Cyriac outlines why efficiency is crucial in manufacturing apparels. “There are no long-term contracts here, unlike in steel for instance,” he says. Manufacturing apparels is more dynamic with everything from pricing decided through negotiations and influenced by market dynamics. “One needs to have high level of efficiency and that helps in areas such as shape, size and reducing wastage. It comes down to high-quality execution and just constantly being meticulous about it,” he adds.

To further increase efficiency, money was invested in upgrading machinery. “It opened up more lines and morale within the organisation took off. Besides, the payback on machinery was at six to eight months,” says Ganapathi. The broad estimate is that capex for a new line is around Rs.12.5 million-15 million with the potential to generate annual revenue of at least Rs.60 million. Today, Gokaldas has 215 manufacturing lines, an increase of 15 over last year. “Incremental capex and high utilisation rates give you disproportionate profit. That is how we have gone about the business,” says Ganapathi. With high fixed costs in this business, Gugnani adds, high utilisation levels are critical.

After getting the “basics” right, as Ganapathi puts it, the new management convinced the existing customers to give them more business. “The good word got around and with strong focus on delivery, we got more ambitious,” he says. Columbia is a case in point where Gokaldas was initially supplying winter jackets and now works with Mountain Hardwear, a subsidiary that caters to the high-performance needs of mountaineering enthusiasts. Ganapathi was also particular about expanding their client base, to include customers across price points, from Walmart and Carrefour to Gap and Banana Republic. As he says, it is an effective way of managing business volatility. While earlier 85% of the business came from their top five clients, today only 70% of their business comes from them.

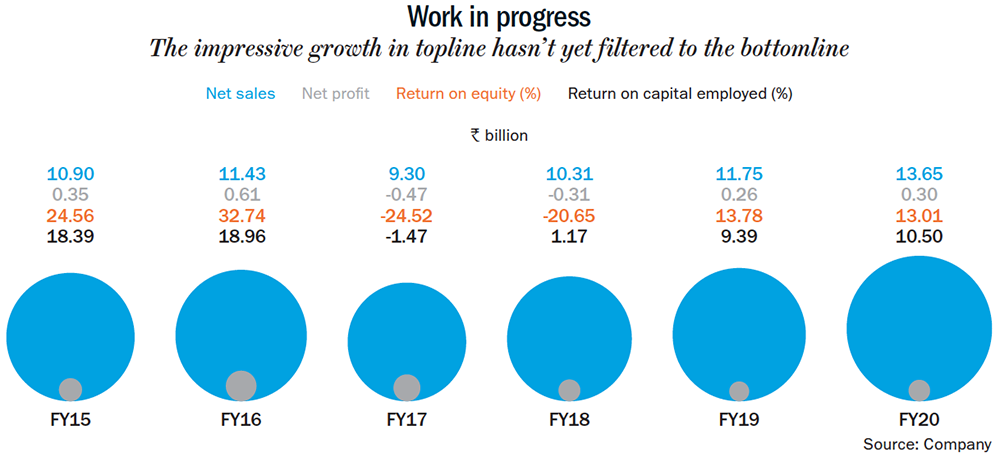

The effort started to show in the financials as revenue took off and the company was now in the black. In FY17, revenue from operations was Rs.9.30 billion, that moved to Rs.10.31 billion the following year and to Rs.13.65 billion in FY20 (See: Work in progress). More importantly, Gokaldas’ bottomline had improved from net loss of Rs.470 million in FY17 to profit of Rs.300 million in FY20. That figure would have been higher but for the withdrawal of the Merchandise Exports from India Scheme (MEIS), which provided duty benefits. The withdrawal was announced this January and the hit Gokaldas took was as much as Rs.410 million. The Ebidta margin had moved from 1% to 7.3%, over the same period.

The effort started to show in the financials as revenue took off and the company was now in the black. In FY17, revenue from operations was Rs.9.30 billion, that moved to Rs.10.31 billion the following year and to Rs.13.65 billion in FY20 (See: Work in progress). More importantly, Gokaldas’ bottomline had improved from net loss of Rs.470 million in FY17 to profit of Rs.300 million in FY20. That figure would have been higher but for the withdrawal of the Merchandise Exports from India Scheme (MEIS), which provided duty benefits. The withdrawal was announced this January and the hit Gokaldas took was as much as Rs.410 million. The Ebidta margin had moved from 1% to 7.3%, over the same period.

In many ways, the recipe for profit is quite clear. According to Gugnani, it is impossible to take on the likes of Bangladesh on labour costs (around $110-115/month compared to $160-180 in India). With the purchase price of apparel fixed, India must look at other areas to make itself relevant. “The way to do it is develop a niche. That could be through new product development or just working with the right customer profile,” he says. Ganapathi sees higher reliance on their design-to-delivery service, as a way out. This service, which includes designing the garments, gives higher margin and now contributes 15-20% of their topline, compared to 3-4% when he took over.

Understandably, the pandemic has affected the company’s operations. During Q1FY21, the garment exporter got an order from the government to manufacture 25,000 PPE kits per day, which helped it get 15% of its capacity running and is expected to contribute 5% to its topline. But, this fiscal the company’s revenue will drop 9% and profit will fall by half, according to a recent report by ICICI Securities. By FY23, the brokerage expects the company to add 50 incremental garmenting lines and rake in revenue of Rs.18 billion.

Ganapathi remains convinced about Gokaldas’ growth prospects and cites the example of Shahi Exports, India’s largest garment exporter today. With a turnover of over Rs.60 billion, it was around the size of Gokaldas when the Blackstone acquisition took place. Shahi managed its client relationships well, invested heavily in building scale and did not take its eyes off cost. “There is clearly a precedent,” he says. With Cyriac and Ganapathi at the helm, the garment exporter is building enough muscle to play in the major league.