On a brisk December afternoon, two attendants at a compressed natural gas (CNG) station near Delhi’s Hazrat Nizamuddin railway station struggle to clear a snaking line of cars and autorickshaws. Asked how many vehicles they fill in a day, one shrugs: “Over 100, 200, maybe 300. You lose count.”

Among those waiting, 27-year-old cab driver Harish Kumar has already spent 30 minutes in the queue, but says this is better than the evening rush. He is among the lakhs of vehicle owners who bought a CNG-powered four-wheeler last year and now endure long waits to refill their cars, a process that should take just 2–4 minutes. This chaos is in sharp contrast to the tranquillity at the nearby Sabz Burj Chowk EV charging station, whose sustainability mandate now extends to providing shelter to a homeless family.

A Sudden Spurt

The difference in the ambience of the two filling stations is also a reflection of the state of two markets—the still niche EVs contrasted with the rapid rise of CNG vehicles. However, the popularity of CNG cars is not quite as old as it may seem from the hustle and bustle of the filling station.

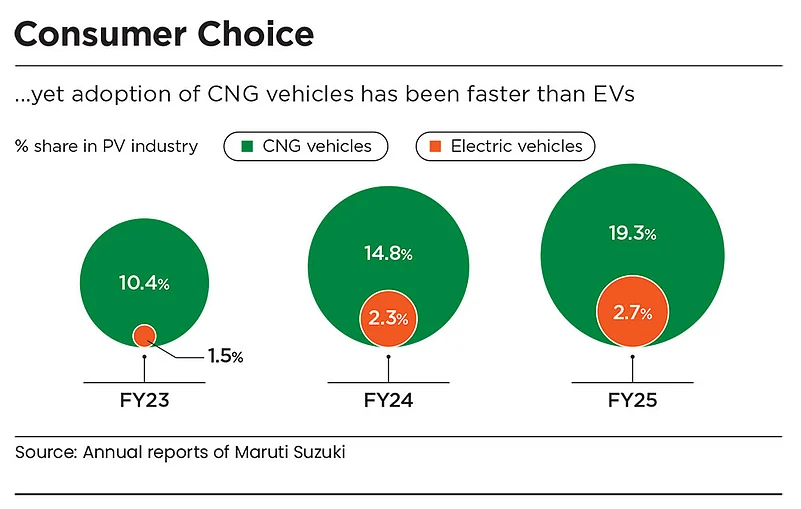

As recently as two years ago (2022–23), CNG vehicles used to make up for 20% of the total sales of India’s largest carmaker Maruti Suzuki. However, by 2024–25, it rose to 33%. Similarly, rival Tata’s CNG share soared from 3% in 2021–22, even lower than its EV share then, to 25% in 2024–25—well clear of its EV sales. For the industry as a whole, the share of CNG cars has almost doubled to 19.3% from about 10% in the same period, and the sales of CNG four-wheelers have increased each fiscal since 2019–20—going from 1.8 lakh units to 4.8 lakh last year, even during the two years when total four-wheeler sales fell.

Yet, there has been no new subsidy scheme, no policy incentive to drive CNG sales in the past 2–3 years. So, what explains the sudden rise, and what does it mean for the Centre’s attempts to popularise EVs?

Stricter Norms

The credit for making CNG mainstream in India must go to the courts, which saw in the fuel a way out for India’s cities from the haze of pollution that enveloped them at the turn of the millennia. Indeed, CNG cars emit 18% less carbon dioxide, 65% less carbon monoxide and over 30% less nitrogen oxides than petrol vehicles, according to a study by the US National Renewable Energy Laboratory. But for nearly two decades, it remained largely confined to public-transport fleets.

The first change came with the introduction of Bharat Stage (BS) VI emission norms in 2020. Overnight, small diesel cars became unviable, leaving CNG as the only cheaper alternative to petrol. Even today, CNG’s economics are tough to beat.

“If you see the mass market—below ₹12–13 lakh—EVs are more or less missing for all players except Tata. However, range constraints persist even in Tata’s products,” says Puneet Gupta, director, India & Asean automotive market, S&P Global Mobility, a data provider.

In fact, a 2024 report from credit-rating agency CareEdge Ratings found that EVs were 80% costlier than petrol cars, compared to a 12% premium for their CNG variants. Much of this price differential can be attributed to the maturity of the underlying propulsion technology and the manufacturing ecosystem around it. A CNG engine still is an internal combustion engine (ICE) with some modifications to enable it to run on gas. Hence, companies could convert existing models without the capital expenditure required for electric platforms.

EVs, by contrast, rely on an entirely different supply chain—a nascent one. On the other hand, India has built a world-class ICE manufacturing ecosystem over four decades with components and vehicles being exported to the US and Europe. Despite government incentives to localise battery manufacturing, no company barring Ola Electric has achieved commercial-scale production so far.

Cheap and Best

As Rahul Bharti, senior executive director for corporate affairs, Maruti, said recently, a multi-powertrain route makes a lot more sense than leaping headlong into the EV transition. “We are ambitious on EVs…[but] the supply chain resilience is not fully established,” he noted.

While high upfront costs—as much as double—make EVs unattractive in front of CNG, it is the running costs that dent petrol’s appeal in front of CNG. This, in turn, owes everything to the government’s tax structure.

Today, petrol is taxed at around 100% while the effective tax rate on CNG is only around 15–20%. This has come to pass as the government has sought to transfer more of the burden of its post-Covid welfare programmes onto the petrol- and diesel-consuming middle class, while CNG, as a cleaner fuel, has been spared.

“There are people who have been driving only CNG cars because they commute a significant distance daily,” says Gaurav Vangaal, associate director at S&P Global Mobility. “For them, it is a good value proposition.”

Other reason is the increasing popularity of shared mobility and commercial fleets. They account for nearly 10% of passenger vehicle sales, and within that, CNG is around 8–10%, according to estimates.

Product innovation is at play too. For years, CNG vehicles were perceived as utilitarian, low-aspiration products: WagonR, Alto, Tiago and Tigor. But the past three years have transformed the market. Major original equipment manufacturers now offer CNG variants of premium hatchbacks and sports utility vehicles (SUVs): Maruti’s Baleno, Fronx and Grand Vitara; Tata’s Altroz, Punch and Nexon. Maruti’s new SUV, the Victoris, has an under-body CNG tank, addressing a long-standing concern of reduced boot space. Tata Motors and Hyundai are offering twin cylinder options to do the same.

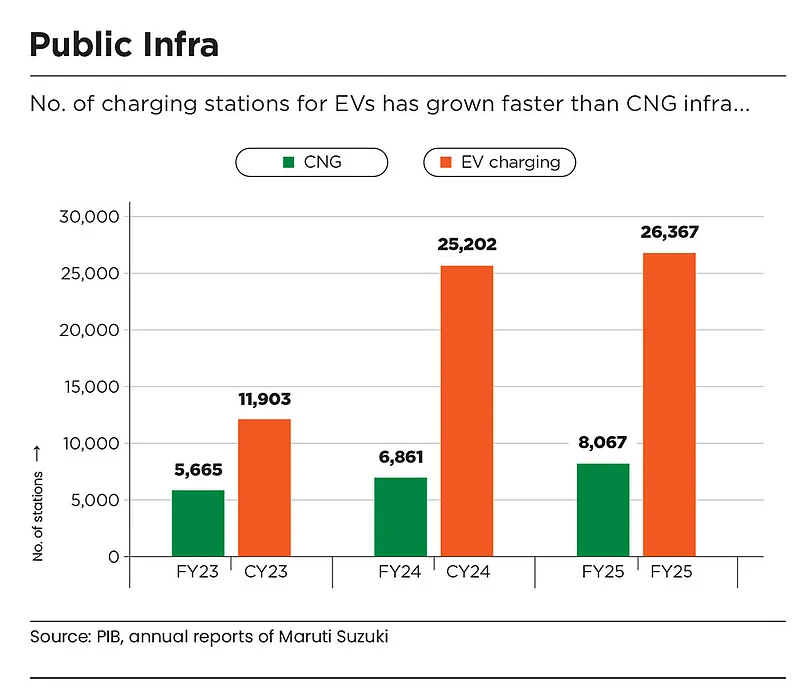

The expanding footprint of CNG fuel stations, growing from 5,665 in 2022–23 to over 8,000 in 2024–25, helps too. Moreover, the government has routinely expressed its desire to take this number to 18,336 by 2034.

Yet another impetus came in 2023 when the Centre implemented the Kirit Parikh Committee’s recommendations to rationalise the prices of locally produced natural gas, bringing predictability to a key CNG input. About 40% of the natural gas used for CNG production is sourced locally while the rest is produced from imported liquefied natural gas.

Bumpy Ride

The path ahead may be uneven for CNG vehicles. India has over 88,500 petrol pumps but only around 8,000 CNG stations. With an average of four nozzles each, these stations can serve about 30,000–32,000 CNG vehicles at a time. Poonam Upadhyay, director at analytics firm Crisil Ratings, sees the queuing at CNG outlets as symptomatic of inherent capacity constraints, adding that the high concentration of CNG outlets in a handful of states also needs to be addressed.

While cost-conscious buyers may put up with long queues, others will look for alternatives like EVs or continue with petrol cars. S&P Mobility’s Vangaal, who sees CNG’s penetration levels plateauing at around 20–23%, points out that this has been the Achilles heel for CNG. “Had it been so convenient, its share would be close to 50% by now. There will always be buyers who would seek convenience over low cost,” he says.

As for EVs, most see it raising its competitive positioning against CNG. Just as corporate average fuel economy (CAFE) and BS norms made diesel variants uncompetitive against petrol and CNG, upcoming CAFE 4 norms, slated for 2032, will make emission standards even more stringent, clearing the path for EVs. By then, experts say, the supply chain for EVs will largely be localised, helping lower its prices. “CNG is a bridge technology from petrol to EV. As soon as EV charging time reduces and running cost becomes lower, CNG will start reducing. Ultimately, it boils down to pride factor and running cost, which is better in EVs,” says Gupta of S&P Global Mobility.

Pulling the Plug?

Even today, EVs are competitive against CNG for heavy users. Crisil pegs the net cost of ownership of an EV over 2,00,000km of usage at ₹16.70 lakh, about 18% lower than a comparable CNG car’s ₹20.46 lakh.

For now, carmakers are bullish on the gas-fuelled vehicle. Maruti targets to have 35% of its sales coming from CNG cars by 2029–30 and only 15% from EVs. Tata Motors, the pioneer of electric cars, looks to grow its CNG share at par with the EV share. But herein lies the rub: CNG is booming at a time when India wants to go electric. If it keeps gaining ground on the back of affordability and availability, it could delay the mass adoption of EVs, especially in the crucial mid-priced segment, where India makes the transition from one technology to another.