RBI’s inflation success may reflect global supply chains, not policy.

Deglobalisation threatens price stability as costs rise across supply chains.

Multiple policy goals could weaken RBI’s ability to curb inflation.

Luck or Skill? Why RBI's Inflation Success May Not Last

Why RBI’s inflation wins may owe more to global forces than policy design

Asset managers try to attract funds by pointing to the high ('abnormal') returns they have delivered in recent years but often add the disclaimer that "past performance is no guarantee of future returns". It is an admission that their success may have been luck rather than skill—and that luck can turn.

The RBI may soon need a similar dose of humility. While its impressive record on inflation over the past decade is widely attributed to the inflation targeting framework it adopted in 2016, an analysis of the available evidence suggests that the success may have been more a case of fortunate timing than effective strategy. In fact, RBI may be about to head into a period of turbulence as the real restraint on inflation—globalisation—is being rapidly undone in a changed global environment.

Past Performance

On the face of it, the RBI’s performance over the past decade has been good. India faced persistently high inflation between 2006 and 2013. These challenges were compounded by the ‘Taper Tantrum’ episode (which led to a sharply depreciating Indian rupee).

These challenges led then RBI Governor Raghuram Rajan to seek to upgrade the RBI’s business model to meet the challenges of a “globalised and highly inter-connected” environment. In central bank jargon, the business model is generally referred to as a monetary policy framework or regime.

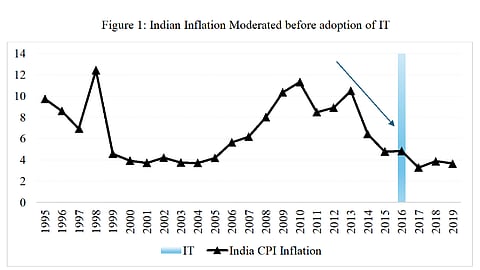

An RBI sub-committee recommended the adoption of inflation targeting (IT) as the monetary policy regime for India and it was subsequently adopted in October 2016.

Since then, a Monetary Policy Committee (MPC) has collectively determined the setting of the RBI’s policy lever—the repo rate—with the objective of keeping inflation within the target range of 2–6%.

The period has also seen remarkable success for the RBI in controlling inflation within the target range. But how much of this success could be attributed to the inflation targeting regime put in place in 2016?

Misplaced Credit

In recent research and in an IMF working paper, Surjit Bhalla, Karan Bhasin and I demonstrate that the credit for this enviable performance of the past may have been misattributed, and the past performance may not be a guarantee of low inflation in the future. Our demonstration is in three acts.

First, we show that credit for how much inflation targeting (IT) has contributed to lower inflation has run ahead of the evidence: IT may have been more placebo than vaccine.

Second, we show that low inflation in India–and globally—has been due to the setting up of global supply chains. The disruption of these chains, first due to the pandemic, then from Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, and, more recently, from tariffs, could provide headwinds that inflation targeting regimes will struggle to overcome.

Third, the achievement of inflation targets has sometimes come at the expense of other goals, such as output growth or stability in the value of the rupee. If these other goals remain salient in policymakers’ minds, keeping inflation in check will prove difficult.

Inflation Targeting : Vaccine Or Placebo?

New drugs generally have to go through clinical trials to establish that they really work. This involves giving one set of patients (the ‘treatment’ group) the drug and another set of identical patients (the ‘control’ group) a placebo. A drug is considered effective if the treatment group fares significantly better than the control group.

Unlike medical science, economic science cannot conduct clinical trials. But recent advances have put forward a method, known as the Synthetic Control Method (SCM), that tries to come close.

The method involves comparing the performance of a country that adopts a policy change with a similar country (“a synthetic cohort”) that does not adopt that policy change. Using this clinical approach, we find that only 9 out of 22 countries that adopted inflation targeting had significantly lower inflation than their synthetic cohort and the gains in those cases were modest.

In other words, we cannot rule out the possibility that, in over half the cases, inflation targeting was merely a placebo and not a vaccine that delivered lower inflation. Hence, reliance on inflation targeting to deliver lower inflation in the future would be more prayer than prudence.

Recently, a couple of other studies, conducted independently of ours and published in the leading journals of monetary economics, have suggested that IT confers only modest inflation gains.

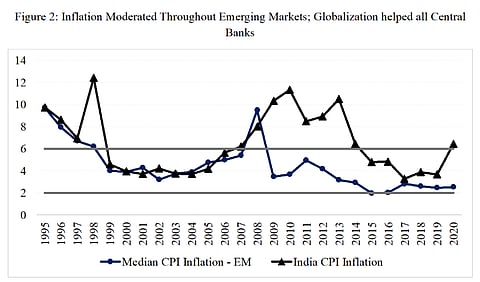

Global Supply Chains And Low Inflation

Our analysis suggests that IT is usurping the credit that rightly belongs to the setting up of global supply chains. The period of subdued inflation from 1985 to 2010, generally referred to as the Great Moderation, was a period of both widespread adoption of IT and the spread of globalisation. Our empirical analysis suggests that it was the latter that was the more important driver of low inflation.

Globalisation had two components. The first was the integration of millions of skilled workers from populous countries like China and India into the global economy.

The second was the liberalisation of capital flows, which allowed companies to move their factories around to reap the benefits of these pools of cheaper labour.

Both forces combined to make what Thomas Friedman described memorably as a flat world, a world in which companies could produce goods by sourcing inputs from the cheapest source available.

That world has changed. Today’s world is one of ‘re-shoring', ‘friend-shoring’ and domestic production.

This pursuit of national security and strategic interests comes at a cost—if companies can no longer seek out the cheapest source of inputs, their costs of production and in turn the prices they charge consumers, will rise. Instead of flying high due to the tailwinds of globalisation, the performance of IT may be brought down to earth by the headwinds of de-globalisation.

Dealing with Multiple Goals

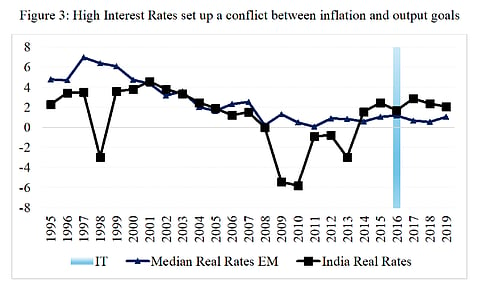

Taming inflation is an important, but not the only, goal of governments. Another important goal is maintaining a good growth rate of output or income.

Given India’s desire to regain advanced country status by 2047, keeping income growth robust is an important goal.

Emerging markets are often keen to minimise fluctuations in the value of their currency, making that a third goal.

It has long been acknowledged that IT can be challenging to implement in the face of multiple goals. For instance, keeping inflation in check might require an increase in the repo rate, but this will dampen output growth.

Conversely, keeping output growth robust so as to regain advanced country status could require easing off a bit on the inflation goal. To its credit, the RBI has generally, but not always, carried out inflation targeting flexibly, giving weight to goals other than inflation.

No Need for Regime Change

Despite our analysis, we do not call for a regime change. To paraphrase Churchill’s remark about democracy, inflation targeting is the worst monetary policy regime, except for all the other ones that have been tried.

However, we do caution against undue reliance on the belief that inflation targeting is a vaccine against future inflation.

Our clinical evidence suggests that IT has been as much placebo as vaccine. The real driver of low inflation may be globalisation, which is currently being unravelled, with a concomitant increase in inflationary pressures.

And as other laudable goals like output growth loom large in the government’s mind, the RBI could find that a single-minded pursuit of inflation targets in the future is difficult. It adds up to a case for RBI keeping handy the asset manager’s mantra: past performance is no guarantee of future returns.

(Professor Loungani is the Program Director for Ms Applied Economics program at Johns Hopkins University. The views expressed are personal.)