It’s been an unseasonably warm summer in Bengaluru this year, but locals could find comfort in the cheery yellow-and-green signs that herald the cool interiors of Cane-O-La, a string of sugarcane juice shops found dotting several neighbourhoods. Inside, it’s tidy and smells fresh, with uniformed personnel bustling about, pulling out evenly cut sticks of chilled, skin-scraped sugarcane from glass-door refrigerators, pushing them through imported machines, and serving up beer-mugs full of frothing cane juice within a minute.

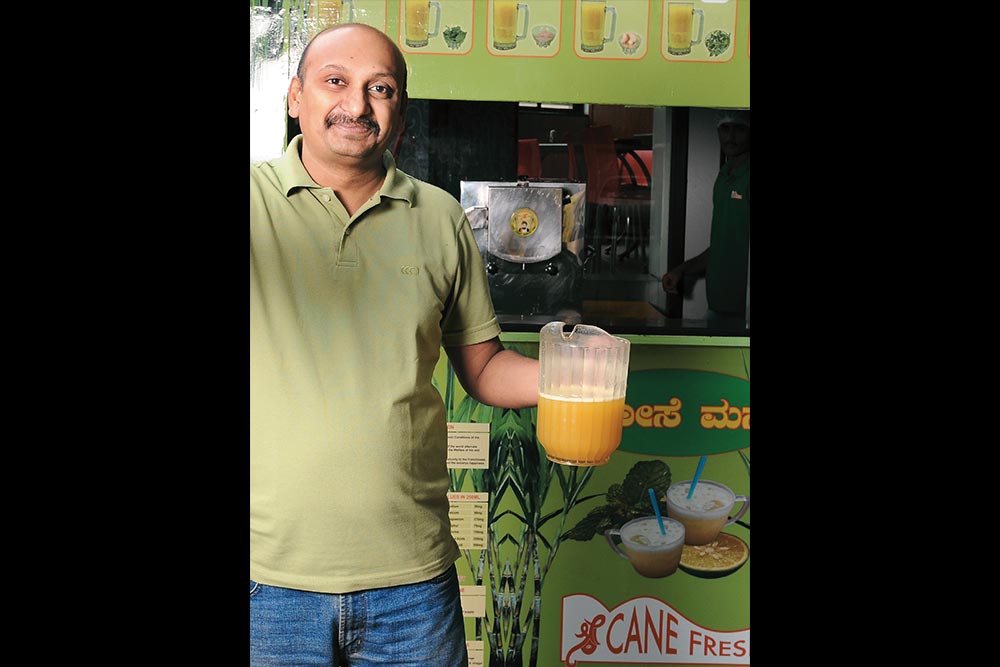

Started in 2007 by the Kakinada-based Mayura Group, which has been running a small clutch of fast food restaurants and bakeries in Bengaluru for four decades, Cane-O-La was soon joined by many others — Cane Crush, Real Cane and Cane Fresh. But while the first two downed shutters pretty soon, the last has survived and grown into a much larger multi-city chain. Launched in 2008 with three counters in Bengaluru and Karur in Tamil Nadu, Cane Fresh quickly expanded to Mysore, Mangalore, Hosur, Dharmapuri, Anantapur, Bellary and more recently, Pune.

Both companies are tasting sweet success. Cane-O-La has 16 outlets currently of which 12 are franchisee-managed. Cane Fresh, on the other hand, has 69 outlets, of which 38 are company owned in corporate and educational campuses in corporate and educational campuses with revenue share arrangements. Both companies serve between 200 and 1,000 glasses of juice at each counter (depending on its size and location) every day during the peak season and about half that during the monsoon and winter months. Back of the envelope calculations suggest that at ₹15 a glass, a busy counter serving 500 glasses a day in peak season could generate over ₹20 lakh in annual sales.

Mayura Group founder G Srinivasa Rao claims Cane-O-La’s turnover, including franchises, is close to ₹4 crore a year; turnover is only ₹50-60 lakh at the holding company’s level. R Swaroop, managing director, Shri Cane Fresh Beverages, says his company-owned outlets bring in about ₹2.5 crore a year. It sounds deliciously tempting, but there are some bitter realities to the sugarcane juice business. “The front end is easy. It’s the back-end that’s the real challenge,” agrees Swaroop.

A tight squeeze

Certainly, it’s not an easy business. For starters, sugarcane juice retailers can’t put a premium price on their offering, despite the higher hygiene and quality standards. Where street vendors sell a glass of the sweet stuff for ₹10-12 a glass, consumers don’t seem willing to pay more than ₹15 for the same in an organised setting. “We don’t add water, ice or sugar. And operating as we do, our cost of production is higher by at least ₹2-2.50 per serving,” says Swaroop. Margins tend to be low, hovering around 10% in high season, bolstered by high sales volumes. They dip lower than 5% in off-season, thanks to the cost pressures of the supply chain and other fixed resources, especially manpower. Rao recalls how, seven years ago, tender coconut was ₹8 and cane juice was ₹10 per glass. “Now, we are at ₹15 per glass and tender coconut costs ₹20-25 each.”

Sourcing cane remains a key challenge. “Unlike an apple or orange, where I can go to anyone for my supplies, in the case of sugarcane it has to be sourced consistently from one place,” he adds. This is necessary to maintain regularity of supply for its monthly requirement of 120 tonnes of cane, and also ensure the juice company gets the specific varieties it needs. For Bengaluru, these are the neighbouring perennial sugarcane belts of Mandya and Maddur in Karnataka, while cane for Pune is sourced from Rahu village nearby.

Specific varieties are important because, unlike roadside vendors, both Cane Fresh and Cane-O-La are looking at more than just sweetness in the juice they sell. Cane Fresh prefers using sugarcane that is less than 11 months old, which, says Swaroop, ensures a low glycemic index and high sucrose levels — the health benefits of such juice are prominently displayed at all Cane Fresh outlets. Cane-O-La’s Rao, meanwhile, sought help from the Sugarcane Breeding Institute in Coimbatore to identify a special breed of the perennial grass called ‘62175’, which has less than 12% sucrose content. “This breed is costlier compared with other breeds,” he says.

Getting farmers to commit to supplies, though, is a problem, since they usually already have ongoing arrangements with jaggery factories and sugar mills that, despite payment and other issues, have been their primary source of income. “To hold an agreement with a farmer is one of the most challenging tasks in this country,” says Swaroop. It’s tougher during festival peaks such as Diwali, when sugar mills need more supplies. Cane Fresh’s solution: paying roughly ₹200 more than the benchmark price set by the government; moreover, its sourcing contracts with farmers ensure that price increases are pegged at 10-15% annually, helping the company maintain its operational costs.

But with sugarcane prices rising each year, maintaining consumer pricing for juice has understandably been difficult. Cane-O-La, for instance, held on to its price of ₹10 per 280 ml mug of its juice till January this year, before hiking it to ₹15. “When we started, sugarcane was selling at ₹800 per tonne, now it’s cruising at close to ₹3,000 per tonne in Mandya,” says Rao. Cane Fresh recently revised its per serving price to ₹20.

Both companies have relatively similar operation models. Cane Fresh’s outlets range from 70 sq ft for takeaway counters to 120 sq ft and above for walk-in outlets that can generate up to 1,000 servings a day. Accordingly, the investment required ranges from ₹5 lakh to ₹7 lakh. “The breakeven for 200 juices-a-day outlets will be close to one year payback of investment,” says Swaroop. Cane-O-La’s kiosks, on the other hand, measure 100 sq ft while standalone outlets need 300 sq ft. Machinery and other investment, brought in by the company, requires close to ₹5 lakh, while the rest of the expense of setting up an outlet depends on the location and the cost of space and is borne by the franchisee.

More importantly, the sugarcane juice business needs to be run like a tight ship, with logistics that could be as demanding as a full-scale corporate supply chain. Cane juice must reach customers within 24 hours after the stalk is peeled. What’s more, only 60% of the juice must be extracted from the cane in its first crush for the most beneficial health benefits. To ensure this, Cane-O-La extracts juice only once. The pulp is transported back to the villages to serve as fuel for jaggery kilns. Cane-O-La requires around 90 tonnes of sugarcane every month.

Do it sweet

“The problem to my mind is that sugarcane juice is a niche segment and has limited appeal,” explains Sridhar Ramanujam, CEO of Brand-Comm, a Bengaluru-based brand consultancy. “Throw in problems such as higher transportation costs etc., and the only way forward to getting premium prices is by building a brand,” he adds. He adds that very little of that has been done so far. Rao appears to have got the first step right by coining a clever and contemporary name for his product. “We named it Cane-O-La to compete with Pepsi Cola and Coca Cola because we want to appeal to young people who can make the more healthy choice with fresh sugarcane juice instead of aerated drinks,” he says.

What Cane-O-La or Cane Fresh possibly cannot match, is the deep distribution muscle of aerated drink manufacturers. Expansion is stymied by transportation costs, and being located close to a cane growing region is crucial to the business model. Cane-O-La has limited itself to Bengaluru with one outlet in Andhra Pradesh’s Kadapa, Rao’s home town.

There are operational issues to contend with, as well. The harvested cane has to be promptly peeled, cut, stored and transported at temperatures of 6-9 degrees Celsius to retain its freshness and juice content. Peeling cane is a labour-intensive job and till such time the peeling process is mechanised, it’s best done at the harvest point, that is, the villages where it’s grown. Cane Fresh, for instance, has a “rural preparatory team” for this. Located in Mandya, the 2,000 sq ft facility has around 30 people engaged in cleaning and peeling the freshly harvested stems.

The peeled sugarcane is packed into ventilated crates and loaded on to one of seven refrigerated trucks that travel to its city outlets. Some of this goes to its four cold storage facilities in Bengaluru, Mangalore and Moodabidri (which services the Alvas College of Engineering campus), where half to one day of peeled cane inventory is stored.

Now, the company is trying to speed up the process by developing an indigenous mechanical peeler. There’s a precedent here: Cane Fresh already developed a crusher in-house. Modern generation crushers are generally from China but the company didn’t find them suitable for Indian conditions. “They could not withstand Indian varieties of sugarcane, which are very thick and strong compared with other countries,” says Swaroop.

Even the joints on a cane stem are so thick that they used to damage the rollers and cause the shaft to break down in the Chinese crushers. It took more than two years, and many rounds of experimentation, for Cane Fresh to finally come up with a “re-engineered” and faster contraption in 2010. Now, Swaroop claims his are among the fastest crushers in the market. “Conventional crushers can give two servings a minute. We manage six to eight juices a minute with our crusher,” he says.

This can make an important difference during peak hours such as lunchtime in corporate campuses and weekends in retail food courts, when customers descend on the outlets in droves. Six of Cane-O-La’s 16 outlets are in corporate office complexes, including one in the Infosys campus, and five as kiosks in malls. Similarly, some of Cane Fresh’s better performing locations include the TCS campus in Pune, BTM Layout and TCS and ITPL in Bengaluru. “Generally, locations that can attract families do better and so we normally choose food courts or standalone canteens,” says Swaroop.

In such locations Cane Fresh works on revenue share arrangements with food court contractors. Here, revenues tend to be higher than in corporate and educational campuses that operate only five days a week or roughly 22 days a month. Another issue with corporate food courts outlets is the seasonality of a different kind where IT companies hire large swathes of workers for specific projects. Swaroop points out: “Once a project is over, 400-500 employees are shifted to another campus.”

Stretch targets

Even if their business models are strikingly similar, both companies have very different growth plans. Cane-O-La’s focus right now is on consolidating its presence in Bengaluru and offering customers reasons to spend more in its outlets. So, it also sells snacks such as chikki from Lonavla and has introduced popcorn machines at a couple of stores. As an experiment, the company is also selling organic jaggery at its outlets.

Swaroop at Cane Fresh, though, is concentrating on selling more juice at more locations — in the next year alone, he plans to add 10 outlets between Bengaluru and Pune. He’s also banking on developing the in-house peeler in the next year. “That will give us limitless capability. We’ll be able to cut degeneration by five or six hours,” he says. It could even help kickstart his ambitious plan to replicate the model overseas, beginning with Singapore, where, he says, “the value realisation will be 10 times more”.

Packaging sugarcane juice for retail consumption, though, is not on the agenda, since that will defeat its health benefits and could take away the freshness appeal. “Cane juice is a functional food, not a fun food,” Swaroop says. Packaging of cane juice is an idea that’s not yet been successfully done in India, confirms Ajay Gupta, CEO at New Delhi-based NIIR Project Consultancy Services. “But it is possible without adding preservatives and the taste more or less remains the same,” he points out. “We have done lab-level production and preservation of cane juice.” Gupta adds that the high cost for setting up an aseptic packaging unit — around ₹3 crore — could possibly be a deterrent. Swaroop estimates that India has a potential for over 1 million outlets in the improved and organised format that he and his contemporaries have attempted to create. If only consumers were ready to pay more.