Hemendra Kothari feels he should have pursued philanthropy a bit more aggressively, like his father did. But then, it’s never too late for the investment banker-turned-philanthropist, who points out that only in the past decade has wealth generation been so high in India. The 66-year-old Kothari knows that well: he raked in ₹2,250 crore in 2006 by selling his 48% stake in his broking and investment banking firm to Merrill Lynch, and in 2009, offloaded the balance 10% stake for around ₹500 crore to Bank of America, which, incidentally, took over Merrill in the aftermath of the 2008 credit crisis. He continues to be the non-executive chairman of asset management firm DSP Blackrock Investment Managers, where he holds a 60% stake. “Today, Blackrock is bigger than the US Fed,” says Kothari, seated in his plush 10th floor office in Mumbai’s Nariman Point. “In India, the [fund management] story is still to play out as we are yet to see big money coming in from pension and insurance players.”

But even as Kothari is keeping a tab on how his business is growing, he has made time for charitable pursuits. Though his family has been running educational trusts and a hospital in Mumbai for generations, Kothari now wants to perfect, or rather professionalise, the art of giving. “First and foremost, after painstakingly creating wealth, it is easier said than done to give it all away,” says Kothari, who set up the Hemendra Kothari Foundation (HKF) in 2008. “But, having said that, there is also a realisation that you are going to leave it all behind. So, while one should enjoy life to the fullest, you also owe it to society for giving you the opportunity. One, however, needs to ensure that the money doled out is used meaningfully.”

Keeping that in mind, HKF engages only with non-governmental organisations (NGOs) that have the necessary prerequisites. “Through trial and error, we have learnt that not all NGOs make the cut,” Kothari notes. “Some do not have the ability and some are not committed enough. So we work with organisations that have the execution capability.” Also, unlike other foundations or charitable organisations that incur a significant sum on just the upkeep of the staff, Kothari has kept his organisation slim and trim. “I have just a 10-12 core member team running the show,” he says. “Though they are paid better than NGO standards, what I have got are professionals who are passionate about their work and are not here for monetary considerations.”

Today, HKF works closely with the Nashik Education Society (NES), which runs 21 schools in Nashik district (Maharashtra). Earlier, the Kothari family’s engagement was restricted to merely acquiring land and constructing school buildings, but today the foundation is focusing more on the quality of education by funding teacher training programmes and vocational training for students. Within NES, HKF is giving a special impetus to schools catering to poor children, such as the Kusumben Kothari Mulinche Shishuvrind (70 girls), the Kamalavati Kothari Mulinchi Prathamik Shala (485 girls) and the DS Kothari Kanyashala (1,590 girls).

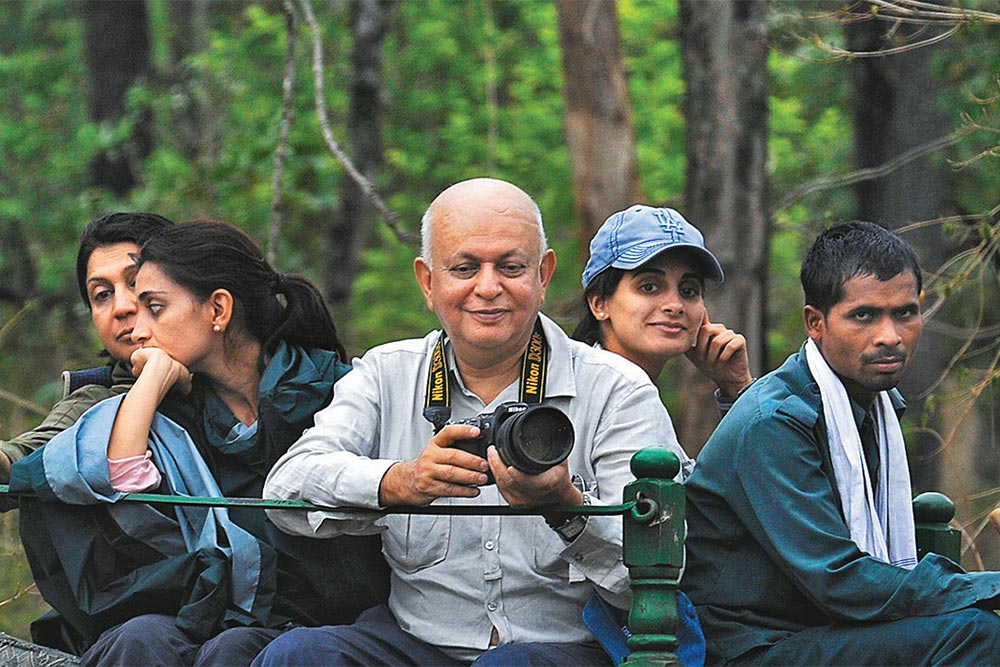

Initiatives on the healthcare front are being pursued under the Wildlife Conservation Trust (WCT), a project close to Kothari’s heart. A green aficionado, Kothari has visited every possible forest in the country and overseas over the past 40 years. “What I realised is that forests are essential for our country as they help in conserving water levels. Besides, increasing man-animal conflict is endangering wildlife as well,” says the tiger lover. “My idea is to supplement government efforts towards conservation, and not to replace them.” WCT was set up in 2008 to protect forest ecosystems and mitigate climate change. Noted environmentalists like Bittu Sahgal and Anish Andheria are onboard WCT, which works in 15 states across 82 protected areas. Kothari is now using the WCT platform to empower forest personnel by providing them with vehicles for mobility, solar charging systems for chowkies and personnel work gear.

More importantly, WCT aims to wean away villagers from depending on forests as a source of livelihood. “Merely educating youths is not enough,” Kothari points out. “So, we ensure that they can avail of short vocation courses such as plumbing, fabrication and masonry, which will help them get jobs in small towns.” WCT also holds health camps in villages along the periphery of forests. “We work with local NGOs as well as individuals as they are well-versed with issues at the grass-root level in such villages,” says Kothari, who continues to visit the wild once in three months with either his daughters or friends. “Forests give me that calming effect and I enjoy doing my bit in return.”