It was September in 1952, and heavyweight boxer Rocky Marciano was facing Jersey Joe Walcott in the ring. This was a much anticipated fight with fans waiting to see how this young brawler would take on a skilled veteran. Walcott had dismissed his opponent, growling at a press meet, “If I don’t take him down, take my name off the record books.” The match was going in his favour too, the first 12 rounds, when Marciano was half-blinded, beat and bruised from the sharply placed jabs and the rain of punches. But the game turned in Round 13, when a well-timed right hook took down Walcott and Marciano claimed the title of the world champion that year.

Battered does not mean defeated and Indian pharmaceutical companies would do well to remember that. They have been facing a series of troubles in their biggest export market, the US. First, there were the patent lawsuits, then the steep fall of generic drug prices, then a tough regulator who came visiting way too often and the cherry on top — the recent allegations of cartelisation to manipulate prices. Now that they are in a corner, can Indian pharma companies counter-punch their way back?

Pharma companies had a good run in the market. Each time the cry for more affordable healthcare erupted in Washington DC, Indian firms with their cheap generics raked in the moolah. They were making the best of their low-cost manufacturing model, estimated to be 15-20% lower than what an average US company spent. But, the incessant thrust on lower pricing by the US government couldn’t have kept their business accelerating forever. The fun began to wane with the Ranbaxy investigations that led to a $500 million settlement, in 2013.

It soon deteriorated into a hopeless situation and, around 2016-17, Indian generics companies decided to take that fighting chance. After all, the US is a crucial market that generates annual sales of $10.5 billion, more than half of their revenue globally. Therefore, generics manufacturers began investing more in the money-guzzling complex generics and specialty drugs space.

Complex generics are expensive to develop since there are two or more drugs in a single dosage; specialty drugs are high-cost too, with innovations such as biologics or transdermal patches.

Troubles beckon

It is ironical that the instability in this sector can be traced back to Paonta Sahib, a place that is believed to have been a refuge for the Sikh spiritual master Guru Gobind Singh for the longest interval. Today, it is an industrial town in Himachal Pradesh and an investigation into Ranbaxy’s facility here is what opened the first cracks in the Indian pharma story.

In 2009, the company was caught falsifying data from this plant, and it quickly led to revoking 25 drug approvals. The US Food and Drug Administration (USFDA) intensified its scrutiny over other Indian facilities as well.

Pharma industry officials describe the Ranbaxy fiasco as a tipping point in FDA’s decision to open offices in Delhi and Mumbai in early 2009. Mark Pohl, an attorney with the US-based Pharmaceutical Patent Attorneys says companies back home were always peeved at what they believed was unfair treatment. “The US pharma majors could be inspected anytime, but that was not possible if the factory was in Hyderabad, for instance,” he says.

But the uneasy level of interest in India was also on the back of increasing complexity of products that Indian companies were manufacturing. Inspections went up from one in two to three years to once or even twice a year. Earlier, the facilities would be intimated 25-30 days in advance, but that changed to as little as 24 hours. India has the highest number of FDA-approved finished dosage facilities (around 200) and it is imperative that they adhere to high standards.

While the companies were trying to cope with the added expenses, US invited more players into the fray. In 2012, the Generic Drug User Fee Amendments (GDUFA) was passed to ensure access to high-quality and affordable generic drugs for patients. To make this possible, approval was given within 10 months, a significant reduction from 26 months earlier. This and regulations leading to faster ANDA (abbreviated new drug application) approvals drew more Indian companies to the US market. It created a hyper-competitive environment, according to GV Prasad, co-chairman & CEO, Dr Reddy’s Laboratories. “Supply increased and demand did not really take off,” explains Prasad.

In FY18, USFDA granted the highest number of drug approvals in its history with Indian companies accounting for around 35-40% of them. Over the past few years, Indian players have launched 75% of the generics in the US, according to an Iqvia report titled US Generics Market – Evolution of Indian Players. The inside joke is that Indian pharma companies spend an unhealthy amount of time gazing at the calendar to see which drug goes off-patent.

With more players in the fray, pharma companies had to cut flab to better their game. “Competition had to make tough choices, and Teva and Mylan were rationalising their portfolios,” points out Nilesh Gupta, MD, Lupin. While Teva took out 40 products, Sandoz completely exited its oral solids and dermatology business, which contributed around 10% to its total turnover of $10 billion. The price erosion, which started to worsen in 2016, has been seeing double-digit decline over the past few years. Thanks to the consistent price erosion, generics make up 15% of the overall US market by value, but 40% in volume. In terms of size, the total US pharma market stands at $480 billion-$500 billion, with generics accounting for $70 billion and the rest coming from innovator products. Both complex generics and specialty drugs make up about 35% of this $70 billion since they also are a part generics, but higher up the value chain.

To cope with the downward pricing spiral, companies started withdrawing ANDAs or holding off product launches because it became unviable. In FY18, companies withdrew about 548 ANDAs, more than double the previous number of 214. Thanks to that supply being choked, prices are now starting to stabilise in the US.

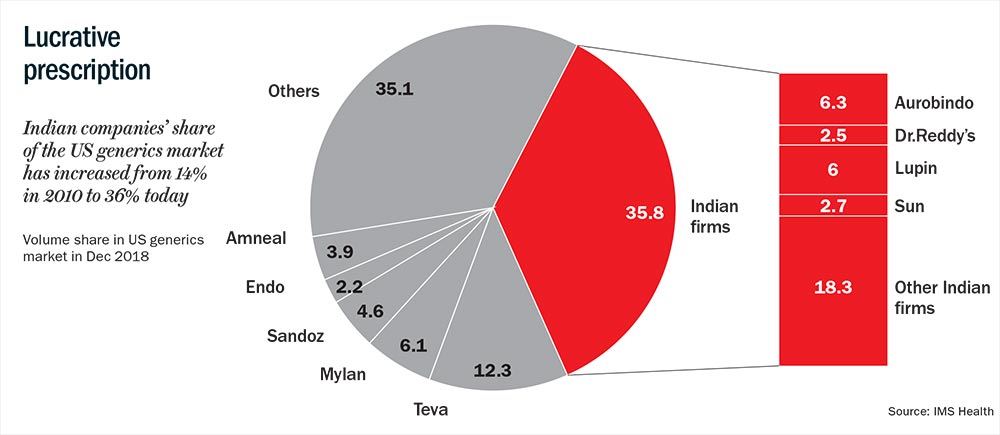

Meanwhile, pricing of generics had absorbed another shock. A year after the amendment began handing out approvals fast and easy, distributors had began banding up. In 2007, ten distributors in the US accounted for 80% of the country’s generics market (See: Lucrative prescription). Today, only three of them — Walgreens Boots Alliance (WBAD), Red Oak and McKesson OneStop — occupy that space. Being vertically integrated players, these distributors are now even more powerful. Besides supplying to other outlets, they own pharmacies and have strong relationships with hospitals. This gave them enormous bargaining power with the companies and resulted in 4-5% discount on average generic sourcing cost, according to the aforementioned Iqvia report.

The business environment was already stifling and then the final volley was fired. Early this May, pharma majors found their names in an antitrust lawsuit filed by 40 US states. The ones named include Aurobindo Pharma, Dr Reddy’s, Glenmark, Zydus, Lupin, Wockhardt and Taro Pharma (Sun Pharma’s subsidiary). The charge was colluding to inflate prices by over 1,000%! According to George Jepsen, former attorney general of Connecticut, rumblings on price collusion started way back in 2000, though it really gained traction much later. “The symptoms were first spotted in July 2014, when there were price spikes,” says Jepsen. “The scope of collusion is obviously very large and is unquestionably wilful. The amount involved will run to several billions of dollars,” he adds.

The uncertainty of the impact of the lawsuit continues to be an overhang on the valuation of Indian pharma stocks, which have been beaten down over the past couple of years. Pohl believes that the political climate is turning hostile. “The worrisome part is that politicians in the US, too, have recently started pushing very hard to restrict the presence of Indian pharma companies,” he says.

Changing times

As the good and easy days in the US seem to be fading away, pharma majors may be right in setting sights elsewhere and considering the complex generics and specialty drugs markets. Here, the competition is limited.

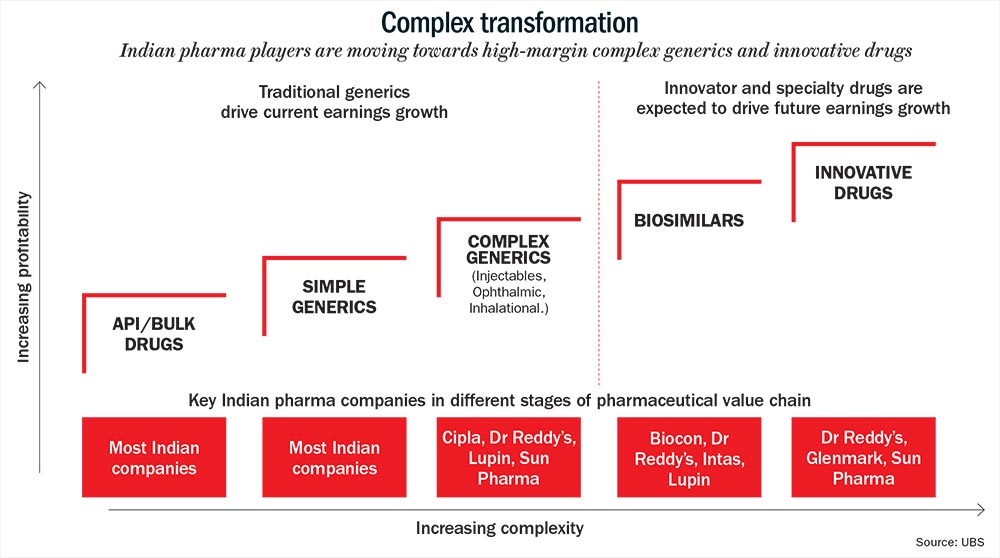

Fewer players mean better margin of around 20-40% (See: Complex transformation). Generics, on the other hand, may yield just 8-10% as average operating margin. “The era of 25-30% margins in generics is a thing of the past. That means innovation will differentiate one player from another,” thinks BPS Reddy, CMD of the Rs.60-billion Hetero Drugs. The Hyderabad-based company derives about 30% of its revenue from the US.

Developing a complex generics portfolio is far more expensive, particularly with R&D and marketing. One specialty drug can set a company back by $100 million, compared to just $1 million to $6 million for a generic. “Clinical trials for a specialty drug alone constitutes 60-70% of the cost. Besides, the whole process from conception to getting the final approval takes five years, during which, the money is completely locked in,” points out Reddy.

However, USFDA guidelines that came in October 2018 indicate that approvals for complex generics will be given faster. They also give more clarity on what pharma companies can do to expedite approvals. While the guidelines focus largely on complex transdermal and topical products ($4 billion market), it is definitely a sign of the regulator’s intent to encourage the development of complex generics.

Lupin’s Gupta says the shift in strategy for his company began over five years ago. So far, he has filed three inhalation products in the US ($4 billion market), and one for biosimilars ($7.8 billion market). The new focus area also includes complex injectables. “There is no doubt that R&D expenses are higher, by more than 20%, and the gestation period is longer, but it comes with significant entry barriers. That means an attractive risk-reward opportunity,” believes Gupta. He adds that the big-ticket investments of the past few years should yield monetary rewards this fiscal onwards.

In the US, Lupin is of the view that women’s health business is also a story to pursue. That explains its acquisition of Gavis in 2015 for $880 million, which brought forth the Methergine brand, followed by Symbiomix Therapeutics acquisition two years later. Gupta shares, “Women’s health space is a $10-billion opportunity, and is definitely a sweet spot for us.” This segment currently contributes 15% of Lupin’s US revenue of $800 million.

The company is hoping to launch about 20 products in the US in FY20, but much of its recovery depends on how quickly it resolves critical compliance issues at its plants in New Jersey and Mandideep. Lupin has four facilities facing scrutiny and is still awaiting the resolution letter for the warning received in 2017 for its units in Goa and Pithampur.

If Lupin is picking its spots, big daddy Sun Pharma is making some aggressive moves, too. Its founder, the reticent Dilip Shanghvi, already under pressure after growth came off in both its key markets — India and the US told Bloomberg, “Sun has invested about $1 billion in its patented-drug programme so far.” The plan is to look at early-stage innovation to ensure that patented drugs, with its higher margin, account for half the revenue. Right now, it gets $250 million of the total US revenue of $1.4 billion. They have two patents in ophthalmology and one in dermatology, while three more are pending in pain management and monoclonal antibodies.

Sun, too, like Lupin, has taken the inorganic route to build competencies in the complex generics space. It was one of the early entrants in the specialty generics space, and has a portfolio of 10 products in the market. Ilumya, used to treat psoriasis, is a significant part of its foray into the US specialty market. After spending $250 million on acquiring and testing the molecule, it was launched in October 2018. While the ramp-up in sales has been slower than expected, increased marketing effort for Ilumya and the launch of its specialty drug, Cequa (used to treat dry eye) in FY20, are expected to drive revenue growth in the specialty segment in FY21.

Not surprisingly, the tack is to play to one’s strengths and then create relevant products. For Glenmark Pharma, the therapy areas of respiratory and dermatology, considered to be the company’s stronghold, are where it wants to build its specialty business in the US. The company’s CMD, Glenn Saldanha, speaks of making its debut in this space with Ryaltris this fiscal, a fixed-dose combination nasal spray to treat allergic rhinitis. “We continue to invest in enhancing our pipeline of specialty products and expect it to start contributing meaningfully to our US revenue in the next few years,” he says. The approach is mixed with a dose of conservatism, as he makes it clear that initially, they will explore partnership opportunities. It is not a route that other major Indian companies have taken, since only smaller players seek partnerships in the US to mitigate risks.

Getting into complex drugs will have the Indian biggies up against global players such as Sandoz and Teva, and it promises to be interesting. For instance, the $1.9 billion Intas, India’s largest privately-owned pharmaceutical company, got into biosimilars around 12 years ago. “We have already launched 12 biologicals in India. Going ahead, we would like to bring a couple of them each year on the global stage,” says Binish Chudgar, the company’s VC & MD. The US accounts for 19% of his revenue and his strategy is to penetrate the generic market, and continue to invest in the specialty business. Currently, the company’s revenue share from specialty drugs in the US is less than 5%.

So far, it has focused on the US hospital business where price erosion, he explains, occurs at a slower pace. This is simply because there are a limited number of FDA-approved facilities manufacturing oncology parenteral and hospital products. “The advantage is that stringent regulatory compliance and high cost of sterile manufacturing restricts the number of new entrants. Eventually, specialty business would become the focus area for all generic companies,” Chudgar predicts.

Dr Reddy’s Prasad says that they are waiting to secure approvals for more than five NDA (new drug application) products in dermatology and neurology. This, he says, will establish the pharma company in specialty. An NDA is the final step in getting approval from the USFDA to market the drug in the US.

This January, the top management of Dr Reddy’s was at JP Morgan’s healthcare conference in San Francisco and, according to media reports, the stated intent was to generate 50% of its US revenue from injectables and other complex dosage forms by 2021. Today, oral solids bring in 80% of its US business which contributes about 38% to the company’s overall revenue.

This “strategic realignment” will also see the easing out of a few commercial operations that do not have critical mass. “The focus will be on developing high-value, meaningfully differentiated products and achieving self-sustainability on our R&D model,” says Prasad. The company invests close to one-third of its R&D spend, which is nearly 8% of its overall revenue, on proprietary products and biosimilars. “We still think market conditions are favourable for us,” says Prasad. Dr Reddy’s plans to expand their product portfolio by launching over 30 products only in FY20, but the mix will include complex generics. While its US pipeline remains strong, the warning letter for one of key facilities is delaying product approvals.

According to Salil Kallianpur, an old pharma hand and founder of ARKS Knowledge, a digital health consultancy, success here calls for a globally scaled company with sustainable R&D, manufacturing and distribution capabilities. “Just possessing expertise in low-cost manufacturing is no longer enough. Having a strong legal team is essential goes without saying. The number of patents to break and bioequivalence to demonstrate on these complex drugs will be in an order of magnitude many times higher compared to plain vanilla generics,” he explains. Just by way of an example, Abbvie, a US biopharmaceutical company spun off from Abbott Laboratories, holds 136 patents for Humira. This is the world’s largest-selling drug raking in over $18.4 billion in revenue, and is used to treat various types of arthritis.

Kallianpur points out that though volume in specialty drugs will be smaller than large-molecule generics, the value generated will be enticing. “Companies will need to be agile to grab available products across therapeutic areas such as dermatology, ophthalmology, cancer, pain and central nervous system. They will need competence to create differentiated products, which could be transdermal patches or MDI (metered-dose inhaler) or pre-filled injectables rather than aiming for leadership in one particular therapeutic area,” he explains.

Final assault

If the biggies are experiencing pain transitioning from plain vanilla to specialty, how are smaller Indian players coping? Vishnukant Bhutada, MD, Shilpa Medicare, a Rs.7.9 billion player in oncology APIs, thinks injectables can be a significant opportunity. “Manufacturing sites are limited and there is no competition from China. Likewise, ophthalmology can be a specialty with complex molecules,” he says. While India files over 200 ANDAs in the US in this area, China does not file more than 30. His company makes only Rs.2 billion each year from the US market and Bhutada is not overawed by the need to scale. “Yes, it is perhaps an advantage, but when it comes to complex generics and specialty drugs, all the players have started from zero. Beyond scale, it is more important to identify that niche where the strength of a player lies,” he says. His focus is on other things like getting the right R&D team. Unlike generics, where the race is to file for approvals quickly, complex generics and specialty drugs demand the right research setup. Bhutada says, “One has to be patient and set at least two to three years aside for Phase I (the earliest phase trial), and that means an approach based on each quarter will definitely not work here.”

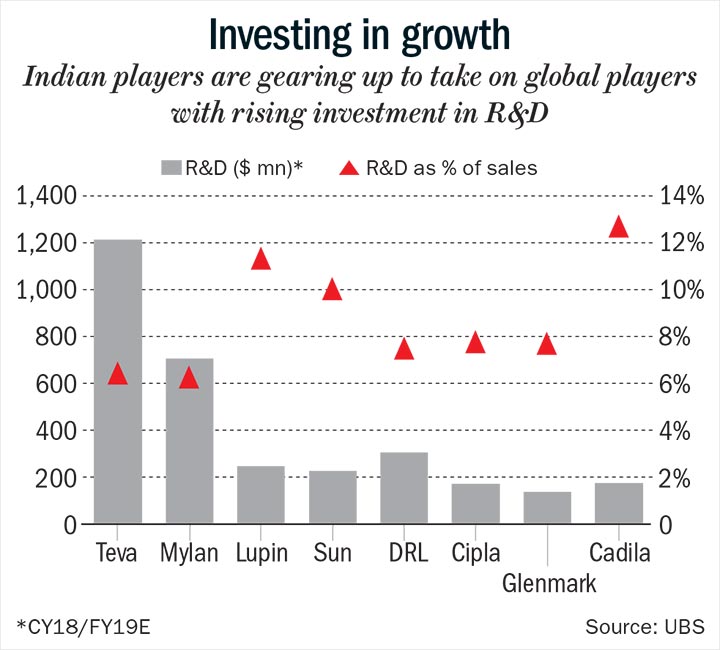

On average, each large player is investing upwards of $200 million each year on R&D, about 10-15% more since the strategy shift (See: Investing in growth). The companies together are spending 20% of their capex on building the specialty business, twice of what it was a few years ago.

That said, there is no question of taking one’s eyes off the generic business, though Saldanha harps on the inevitable transition into specialty or innovation. “Specialty, while being exciting, is still at an early stage and the plan is to continue to file and launch generic products,” he says, though the growth of their US generics business will be in single digits for a while. There is a second patent cliff coming and the yields won’t be loose change. Kallianpur says, “Drugs raking in sales worth $251 billion are set to go off-patent between 2018 and 2024.” With a chunk of the drugs going to be in the complex generics space, Indian pharma is looking to regain some of its lost glory.

But, it won’t be an easy transformation for the companies. They are used to quick action and cultivating a sense of urgency, while the new business calls for oodles of patience. While large companies such as Sun Pharma, Lupin, Cipla and Dr Reddy’s have built a strong pipeline of complex generics and specialty drugs, the ones that have been launched are taking time to scale up and are costing the company more marketing dollars. However, it is a transition that the companies must make for an overall sector re-rating.

With all the recent troubles, the stock price of leading pharma majors has gone down by more than 40% over the past couple of years. “The FDA will continue to tighten processes and compliance costs will only go up, making it very difficult for those in generics,” says Reddy. There is no doubt that pharma companies have been driven to the ropes, like Marciano was that day by Walcott. But they don’t seem to be giving in. They are pulling themselves back into the fight, learning to evade quick jabs and waiting to land that knockout punch.