There’s a poem titled The Mountain and the Squirrel. It’s by American philosopher Ralph Waldo Emerson, and it’s on a quarrel the two have. The mountain calls the other a “little prig” and, the furry one replies: “Talents differ; all is well and wisely put;/ If I cannot carry forests on my back,/ Neither can you crack a nut.” Bottomline: Being small has its merits, even in e-commerce.

In the initial surge, investors poured money into the likes of Flipkart and Snapdeal, the big guys. The hype was around being everything to everyone, to grow mountainously in horizontal e-commerce. The sites were selling everything, from earbuds and scrubbers to high-performance stereo and vacuum cleaners. Then, a handful of entrepreneurs decided to take the side door. They decided to solve pain points of access to quality products in verticals such as babycare, eyewear, beauty, innerwear and even furniture. These niche players have proved to be more capital efficient, even as the horizontal players continue to guzzle cash. Investors, who had been skeptical about these specialist businesses, have begun to show interest in them over the past three to four years. Tritely put, small has become big.

“Building leadership in verticals is much easier than building leadership in horizontals as it tends to be a winner-takes-all market. So, investors back the market leaders… because you cannot come from behind and catch up in these segments,” says TCM Sundaram, founder, Chiratae Ventures. According to Forrester Research, the Indian vertical e-commerce space is pegged at about $10 billion, excluding sales of these companies from offline channels.

But, COVID-19 has knocked every business out of its rack. Like most other businesses, vertical e-commerce companies, too, have had zero revenue during the lockdown. They aren’t changing their strategy yet, to tide over this period. They have simply begun to focus more on better financial management, and are going slow on expansion.

LEADER TAKES A BOW

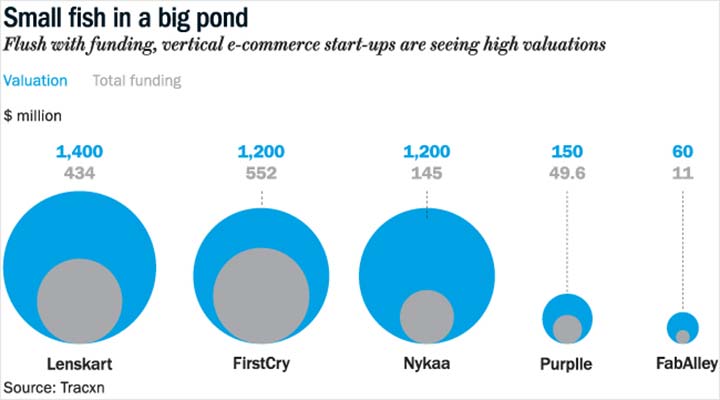

These niche players, including the likes of Lenskart, Nykaa, FirstCry, FabAlley and Purplle, which are collectively valued between $3.6 billion-$3.8 billion, are hoping their cash reserves will see them through most of 2020. Call it a stroke of luck or by design, most of these companies have raised significant capital in the past 12-18 months from investors. FirstCry, Nykaa and Lenskart, with the largest market share in online babycare, beauty and eyewear segments, are the highest funded start-ups in these segments (See: Small fish in a big pond).

FirstCry, a babycare e-tailer, was launched in 2010 when Supam Maheshwari realised that options for baby products were limited. He used to buy plenty for his son on his business trips overseas. It was his second stint with entrepreneurship. His first was in 2000, when he started his e-learning venture Brainvisa Technologies, which he later sold to Indecomm Global for $16 million in 2007.

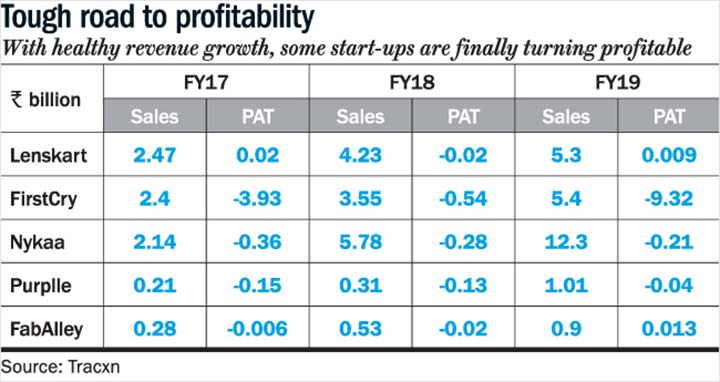

A witness to the dotcom bubble and the slowdown brought by the Lehman bankruptcy, Maheshwari knew the importance of having cash and cost efficiency. Along with his partner Amitava Saha, he ensured that FirstCry was built on frugality. In FY18, it significantly reduced its losses to Rs.545 million, from Rs.3.93 billion in FY17, according to Tracxn (See: Tough road to profitability). During the same period, its revenue recorded 48.03% growth, to Rs.3.55 billion from Rs.2.4 billion.

Since its launch, it has garnered more than $525 million from investors. This includes a $400 million commitment from Softbank, making it the fund’s largest investment in the vertical e-commerce space. While $300 million has already been invested, FirstCry, which is now valued at $1.2 billion will get the balance 100 million in January 2021. In comparison, its competitor Hopscotch has managed to raise about $30 million.

Softbank has also bet on Lenskart, the largest player in the eyecare space, investing $231 million in December last year. Started by Peyush Bansal and Amit Chaudhary in 2010, Lenskart has raised about $380 million till date from investors. The idea to launch the business came to Bansal when he stumbled upon a report that stated - of the 600-700 million Indians who needed spectacles, only 170 million used them. “It was a huge problem that needed to be solved,” he says. Drawing on his 2008 experience at Flyrr, an eyewear business based in the US, Bansal founded Lenskart. Today, the company is valued at $1.4 billion. Its revenue rose by 56% to Rs.5.3 billion in FY19, from Rs.4.23 billion in FY18, while the company turned profitable in FY19 clocking a profit of Rs.9 million from Rs.2 billion loss for the same period.

Like Bansal and Maheshwari, Tanvi Malik and Shivani Poddar, too, noticed gaps in a major industry – fashion. While working the 9-to-6 grind in their corporate jobs at Titan and Avendus Capital respectively, they realised that they had limited affordable shopping options, especially in western wear. In a survey conducted by them, 500 working women shared that they faced a similar problem as no Indian company could keep up with the global trends set by brands such as Zara, Asos and H&M. To fill that space, the duo launched FabAlley in June 2012.

Today, about 40% of its online sales come from the US, UK, South East Asia and Middle East. Its growing online presence has helped the company scale up its gross revenue from Rs.500 million in FY16 to Rs.1.25 billion in FY19. In fact, the company has turned profitable posting a net profit of about Rs.13 million in FY19.

Two other players that have also turned profitable are Nykaa and Purplle. Started by investment banker Falguni Nayar in 2012, Nykaa offers over 1,000 beauty and wellness brands and attracts 50 million visitors a month. It doubled its revenue to Rs.12.3 billion in FY19 and narrowed its loss from Rs.280 million to Rs.210 million. Its competitor Purplle, on the other hand, clocked revenue of Rs.1.01 billion and narrowed loss to Rs.40 million.

PRIVATE PLAY

So, what is working in favour of vertical e-commerce players? For one, there is less competitive pressure, with no crazy discount wars. Verticals such as beauty, eyewear, babycare and apparels are large spaces that allow these players to build scalable businesses. “Beauty products have a wide range and getting them is not easy. So that was a pain point Nykaa solved. The business also lent itself to private labels so that meant higher margins. Logistics and shipping don’t cost much for most beauty products,” says Gopal Srinivasan, chairman, TVS Funds. For Nykaa, private labels contribute about 15% of overall revenue and the aim is to take it to 20% over the next few years.

Foraying into private labels increased gross margins to 60-65%, for some of the vertical e-commerce companies. For example, Purplle, which makes 35% of its revenue from private labels, earns about 30-40% margins on other brands’ products and 40-60% on its own labels. “You can dislodge a brand by competing on price,” says Rahul Dash, co-founder and COO of Purplle. After its pivot from an inventory model to a marketplace in 2015, the start-up began to use sales data and AI to identify gaps where it can launch products of its own. Even FabAlley launched Indya, an ethnic-fashion brand in 2016.

For Lenskart, almost 90% of its overall revenue comes from private brands — Vincent Chase, John Jacobs, and Aqualens, its contact lens offering. While John Jacobs is priced at a premium, the Vincent Chase line is positioned as the affordable range with two frames being offered at Rs.999. But even at those prices, the start-up is able to build in hefty margins, as it controls everything from design to manufacturing to retailing.

GOING OMNICHANNEL

Apart from using private labels, the vertical e-commerce players have also been the pioneers of pursuing an omnichannel strategy to reach out to customers. For instance, the founders of FirstCry realised early on that they needed to have a physical presence as well. They decided to go with the more capital-efficient franchisee-led model for their omnichannel foray and set up their first store in Bharuch, Gujarat in 2011. Being the first online retailer to go offline, its store count has reached 400, and the plan is reach 1,200 stores in the next couple of years.

While the franchisee bears the cost of real estate and shop interiors, FirstCry supplies the inventory, allowing the company to scale rapidly. These stores help the company sell its inventory faster, generating precious cash flow. “The same customer can buy the product at the hospital, the shop, in his neighbourhood or online. It is all about how many ways do you have to get to the customer and the more you have the better,” says Ben Mathias, partner, Vertex Ventures, one of the earliest investors in FirstCry.

Lenskart took to the omnichannel route in 2015. A majority of their stores are franchisee-led, just like FirstCry’s model. “We want to expand from the present 500-odd stores to 2,000 over the coming years. We are in about 100 cities now and the plan is go deep at the taluka (sub-district) level,” says Bansal.

In the same year, Nykaa started with two stores, one each at Mumbai and Delhi airports. “It was to improve the brand’s overall visibility,” says Srinivasan. The company soon found that 15% of its customers only shopped online, 15% only shopped offline, and nearly 70% of its customers shopped offline and then replenished online. So they realised that they needed to be available at multiple touch points and began increasing the brand’s presence in 2017. It is currently working on expanding its offline footprint from 38 stores to 180 by 2023. Poddar, co-founder of FabAlley, says that offline turned out to be a profitable avenue for the company despite being capital intensive. About 70% of its overall revenue comes from their 30 standalone stores; the company also has around 350 shops-in-shops.

“In offline, it is all about finding the right location and hitting all the metrics. If any store is not getting the numbers, you need the discipline to shut it down,” explains Mathias. As per industry estimates, store rentals and operations add upto anywhere between 18% and 22% of expenses.

While omnichannel and private labels have given better reach and margins, can these companies continue to scale and remain on the path to profitability? Sundaram says even if the market leaders have a significant share online, the overall penetration is still low thus offering a lot of headroom for growth. For instance, the mother and childcare space is worth around $74 billion. “With over 25 million babies born in India annually, we practically create a Spain every year. So, there is no dearth of growth opportunities,” says Maheshwari.

The vertical players are not leaving anything to chance and are looking to capture more wallet share of their consumers by foraying into adjacent categories. For instance, Nykaa is now looking to replicate the success it had in beauty, in its fashion and accessories’ business. “While it is a tough business to execute, the market opportunity is much larger compared to beauty. We will be using the same playbook that we used in the beauty business, where we carefully curate our products and content, and pursue partnerships with global brands,” said Nayar in an earlier interview with Outlook Business.

FabAlley also recently launched its jewellery brand, Zyra, to cater to the millennials’ accessory tastes. FirstCry acquired Oi Playschool (for an undisclosed sum) aiming to capture the initial years of the child after birth. It runs on a franchisee model and has about 55 centres in Hyderabad and Bengaluru.

Investors feel diversifying into adjacent categories in the same vertical makes a lot of sense as consumption power is going up. “The middle class will soon make up 50% of the population with growing purchasing power,” says Avinash Fafadia, partner at Blume Ventures, one of the investors in Purplle. Investors are betting on the fact that consumers will get more comfortable transacting online thus leading to a brand’s growth. And, that will drive its offline presence as well. For now, it does look like vertical players are sitting pretty at the top.

PLAYING CATCH-UP

Of course, the market size and the growth potential hasn’t escaped the attention of the two of largest horizontal players — Amazon and Flipkart, and they too are looking to snag a piece of the beauty and the babycare market. But investors believe it will be hard for them to replicate the domain expertise and the depth of the offerings.

For instance, Amazon India offers over 20,000 brands in the beauty space but it still falls short of the 50,000 that Purplle offers. The horizontal players provide a range of products and offering a large catalogue in every category without compromising on margins would be difficult, explain the investors.

Both Amazon and Flipkart have also tried their hand at babycare but have struggled to build in that category. “They are fighting too many fires at the same time,” says Mathias. In the mean time, the e-commerce heavyweights continue to clock significant losses. While Flipkart’s Group revenue grew by 50% to Rs.306.44 billion in FY19, its losses were still a staggering Rs.172.31 billion.

What’s clear is that the biggies are ceding ground to these specialty players. The Indian e-retail market’s GMV stood at around $30.8 billion in 2019 and is likely to grow to $67.7 billion by 2022, wherein the share of big and small or emerging verticals will scale up from around 20% to 30%, stated a December 2019 report by consulting firm RedSeer. For horizontal players, this indicates a fall of 10% market share by GMV from 80% ($24.64 billion) in 2019 to 70% ($47.39 billion) in 2022. However, with COVID-19 playing spoilsport, the growth story might lose some steam for sure.

STAYING THE COURSE

2019 was a breeze, in a sense, for vertical players. But 2020 will test their mettle. It is going to be about staying the course, while being prudent about finance. All the five leading vertical e-commerce players saw their topline in FY19 grow in the range of 25-70%. But since March 23, revenue has been a trickle.

For FY19, Delhi-based fashion house, High Street Essentials, which owns women-centric fashion brands, FabAlley (western wear) and Indya (Indian ethnic wear), clocked 70% growth to hit net revenue of Rs.900 million, and profit of Rs.13 million. While Poddar believes FY20 growth will be much like FY19, growth will fall sharply in FY21, growth will fall sharply. Since 70% of its revenue comes from offline stores, largely from Indya stores, the lockdown has meant a sizeable loss of revenue, which will reflect in the current fiscal. Poddar says that HSE could end up closing the fiscal 25% lower than FY19. “Metros, which are still in the red zone, are our primary drivers,” reveals Poddar.

The SoftBank-funded Lenskart Eyewear Solutions has projected a 20% growth in sales in FY21, even as its FY20 financials are awaited. “At a time like this, we are still hoping to record 20% growth for FY21… It is obviously not as much as we have usually recorded in the past, and is certainly not going to be in the 40%-50% revenue growth range that we anticipated earlier, prior to the pandemic,” Bansal, was quoted in a newspaper report. The Faridabad-based eyewear solutions company, which has 600 stores, has reopened about 100 stores in green zones, and expects prescription glasses and contact lenses to drive revenue for FY21.

It is planning to open another 200 stores this year, mostly in Tier-I and Tier-II cities, with a new model of operation. Instead of fixed rental, the company will enter into a revenue share with landlords. The company, which sold six million pairs in FY20, is eyeing sales of six million pairs in FY21 because it expects demand to pick up from the third quarter. HSE, which was looking at 50 stores over the next one year, is now going slow on its expansion. “We are at 32 stores, and at best we might add five stores during the year,” mentions Poddar.

FUNDING CUSHION

Even as revenue has fallen off a cliff, the good thing for leading vertical players is that they are adequately capitalised, having managed to raise money or being in talks to raise money. Lenskart’s Bansal had said, in an earlier interview, “We had raised financing right before the pandemic was declared. Otherwise the situation could have been quite different. This definitely allows us to cruise.” The start-up was catapulted into the unicorn club in 2019, when it raised $330 million from SoftBank’s Vision Fund-II and private equity major Kedaara Capital.

Last year, with over 1,000 private equity and venture capital deals valued at $45 billion - the highest in the past decade - consumer technology attracted $7.7 billion in investments. Almost half of these investments were in vertical e-tailers/marketplaces and fintech companies.

The companies aren’t squandering their stroke of luck away. HSE’s FabAlley will focus on a lean working capital model by managing its inventory and seasonal collections. They have always had discount sales, since they are in the business of fast fashion, but now they will offer steeper discounts. It will be at 35%, much higher than the regular 20-25%. FabAlley will also slow down on stocking new inventory and instead will carry forward a few of its bestselling lines. HSE, which raised venture debt of $1 million from Trifecta early this year, is now looking at a $3-million fundraising plan. “We don’t want to dilute our stake just for the sake of expansion and working capital needs. Hence, we decided on venture debt,” says Poddar.

At FirstCry, too, ‘lean’ is the keyword. Mathias says they have advised all companies in their portfolio “to cut unnecessary costs and prepare to stretch their cash reserves for as long as possible”. Mathias says that the start-up anyway runs a tight operation and has a strong balance sheet, so not too many measures were required. The company has also emerged as a leader in its category after acquiring Mahindra Retail, which owns the BabyOye brand, in an all-stock deal worth $50 million.

Mathias says that the focus now is on making the supply-chain more efficient, to drive up gross margins and unit economics. In FY19, FirstCry clocked revenue of Rs.5.35 billion. For FY20, the company has said in its regulatory filings, it expects revenue of Rs.20.33 billion. “Impact to growth projections, if any, will be positive,” he says, explaining that it comes under the non-discretionary spend and will benefit from the shift to online buying.

As the sun sets on this pandemic, these vertical players could emerge as agile machines operating on healthy cash flow. The biggies are also watching the game closely and might pull out their checkbooks for many of them.